“You’re Mine Now,” Said The British Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved For Days

September 1945, 1430 hours. A railway siding two miles west of Asheford, Kent. The air tasted of cold dust and rain that hadn’t yet fallen. Clouds hung low and gray, pressing down on a landscape stitched together with bomb craters and patched up rails. The war in Europe had ended four months ago, but its debris still moved through Britain like a slow river.

Trains full of displaced people, convoys of captured equipment, and on this particular Thursday afternoon, a freight car packed with 47 German women pulled from the ruins of the Vermacht’s auxiliary core. They stepped down onto gravel slick with oil, blinking against the pale light like prisoners surfacing from a mine. Their uniforms, once pressed and functional, hung loose on frames hollowed by weeks of near starvation in American transit camps.

Hair matted, skin gray, eyes that had learned to expect nothing. A British sergeant stood waiting, clipboard in hand, flanked by two younger soldiers who looked barely old enough to shave. He watched them stumble into formation, some clutching satchels, others empty-handed. One woman swayed and nearly fell.

The sergeant stepped forward, steadied her with a hand under her elbow, and said something quiet in halting German. Then he nodded to the younger soldiers. They moved down the line, handing out tin mugs filled with tea. Hot, milky, real sugar dissolved at the bottom. The women stared at the mugs as though they might vanish.

Some drank immediately, scolding their tongues. Others held the warmth between their palms and wept without sound. The sergeant returned to his clipboard, his voice flat and procedural. “Processing at the camp, medical exam first, no rough treatment. You are prisoners of war under British custody. That means something here.” He paused, glanced at the women, then added in slow, careful German, “You will be fed.”

One of the prisoners, a young woman with hollow cheeks and weak- colored hair, looked up at him. Her lips moved as though testing words she no longer trusted. The sergeant met her gaze for half a second, then turned and walked toward the waiting trucks. Behind him, the women climbed aboard, clutching their tin mugs like talismans.

Civilization, it turned out, sometimes announced itself in whispers. If stories like this remind you why history matters, consider subscribing. We’re building something careful here. Something that listens before it speaks. The women on that train had carried certain beliefs with them across the shattered map of Europe.

Beliefs fed to them in cramped barracks and printed in newspapers that no longer existed. Beliefs whispered in the chaos of retreat. They had been told that capture by the British meant brutality, starvation, forced labor until collapse. that enemy soldiers would strip them of dignity before stripping them of life.

That women, especially women in uniform, would be treated with particular cruelty. Revenge for the Blitz. Retribution for years of war. Some had heard worse. Whispers of Soviet camps where prisoners froze or starve by the thousands. Stories of American transit stations where rations disappeared and chaos reigned. The propaganda had been clear.

The allies were monsters in different uniforms. Surrender meant trading one death for another. So when they stepped off that train in Kent, stomachs knotted with hunger and fear. They expected the worst. Expected shouting, expected blows, expected to be sorted like livestock and forgotten. What they received instead was a tin mug of tea.

And that small impossible gesture cracked the foundation of everything they thought they knew. The camp sat on the edge of farmland that rolled toward the downs. A series of low wooden huts surrounded by wire that looked more administrative than punishing. Guards patrolled, yes, but without the tension the women had braced for.

No dogs, no shouting, just the rhythmic crunch of boots on gravel and the low murmur of men speaking English too fast to follow. Processing took place in a converted barn. The women were called forward one at a time, names checked against manifests typed in triplicate. A British officer, older with graying temples and tired eyes, sat behind a desk and asked questions through an interpreter.

“Name, rank, unit, service dates, medical conditions.” The woman with colored hair, her name was Ilsa Hartman, 23, formerly a radio operator, answered carefully. She had learned in the American camps that honesty could be dangerous, but the officer barely looked up. He made notes, stamped a form, and waved her toward a door marked medical.

Inside, a British army nurse waited, middle-aged, efficient. She gestured for Elsa to sit, then examined her with brisk competence, checked her throat, her eyes, her pulse, asked about lice, about disease, about injuries. When she pressed fingers against Elsa’s ribs and felt bone too close to skin, the nurse’s mouth tightened.

She said something in English to an orderly, who returned moments later with a biscuit and a small tin of condensed milk. The nurse opened it, poured a measure into a cup, added hot water, and handed it to Elsa. “Drink slowly,” she said in accented but clear German. “Your stomach will rebel if you rush.” Elsa stared at the cup. The sweetness rising from it made her throat ache.

She wanted to ask why, wanted to know what this kindness would cost. But the nurse had already turned to the next woman in line, her movements calm and methodical. The tin mug of tea had been the first crack. This was the second. Small gestures, yes, but they landed with the weight of landmines in reverse, each one dismantling certainty.

That night, in a hut with proper bunks and clean blankets, Elsa lay awake and thought about the nurse’s hands. Steady, professional, unmarked by cruelty. She thought about the tea on the platform, the biscuit, the way the sergeant had steadied the woman who stumbled. She thought about propaganda, and for the first time since the war began, she wondered what else had been a lie.

What Elsa could not have known, lying in that hut with 46 other women, was that her treatment was not an accident. It was policy. Britain’s approach to prisoners of war in the Second World War was built on four pillars, each reinforced by centuries of military tradition and hardened by pragmatism. First, security. Prisoners behind wire could not fight. Humane treatment reduced escape attempts and unrest.

A well-fed, fairly treated P was easier to guard than a desperate one. Second, intelligence. Prisoners who felt respected were more likely to cooperate. Interrogations conducted without torture yielded better information. Trust, even fragile trust, open doors that brutality sealed shut. Third, diplomacy and reciprocity. Britain held German PS. Germany held British PS.

The Geneva Conventions signed in 1929 created a web of mutual obligation. Treat prisoners well and your own soldiers stood a better chance of decent treatment abroad. Violate the rules and the enemy had license to do the same. Reciprocity was insurance written in policy. Fourth, morality. Britain had fought this war in part to defend civilization against barbarism.

To torture or starve prisoners would be to become the enemy. The Royal Army operated imperfectly but deliberately under the belief that victory without principle was hollow. The numbers bore this out. By war’s end, Britain held over 400,000 German PS on its soil.

Red Cross inspectors visited camps regularly and found conditions that while Spartan met international standards. Mortality rates among German PSWs in British custody remained extraordinarily low, under 1%. Food rations, though modest by civilian standards, met minimum caloric requirements. Medical care was provided. Work assignments were regulated. Abuse, when it occurred, was investigated and often punished.

This was not kindness in the sentimental sense. It was restraint. civilization under pressure, choosing order over revenge, even when revenge would have been easy. The British understood something fundamental. Cruelty is a choice, and they chose otherwise. The first meal came that evening, served in a mess hut that smelled of boiled potatoes and institutional disinfectant.

The women lined up with tin plates, moving slowly, uncertain. A British cook, sleeves rolled to his elbows, spooned portions without comment, mashed potatoes, tinned peas, a slice of spam glistening with fat. Bread, thick and pale, with a scraping of margarine. It was plain food, ration food.

But it was hot and it was real, and it was more than most of them had seen in weeks. Elsa sat at a long wooden table and ate with trembling hands. Across from her, a dark-haired woman named Jizela wept quietly into her potatoes, shoulders shaking. Others ate in silence, chewing slowly, as though afraid the meal might be snatched away.

One woman laughed, a sharp, brittle sound that broke off into a sob. The guards stood along the walls, watching but not interfering. One of them, a young private with red hair and freckles, shifted uncomfortably, then looked away. Later, Elsa would learn his name was Collins. Later still, she would learn he had a sister who had died in the blitz.

But tonight, he was just a shape in olive drab, and she was just a woman trying to remember how to swallow without crying. After the meal, a British officer stood and read from a typed sheet. Rules: simple, direct, enforced. No unauthorized movement beyond the huts. No contact with civilians without permission. Work assignments would begin within the week. Letters could be written and would be censored but delivered. Medical concerns were to be reported immediately.

Refusal to cooperate would result in loss of privileges, not physical punishment. “You are prisoners,” the officer said in clear, slow German. “But you are not animals. Behave accordingly, and you will be treated accordingly.” He folded the paper and left.

That night, Elsa lay in her bunk, a real bunk with a mattress stuffed with straw and a blanket that smelled faintly of soap and listen to the sounds of 46 women breathing in the dark. Some snored, some whispered, some prayed. She thought about the mug of tea, the nurse’s hands, the food that had filled her belly for the first time in weeks.

And she thought about the officer’s words, “You are not animals.” It was such a small thing to say, such a low bar to clear. Yet, after everything they had endured, it felt like a revolution. Within a week, the women were assigned to work details, not as punishment, but as policy. The Geneva Conventions permitted P labor, provided it was non-military, compensated, and conducted under humane conditions.

Britain, desperate for agricultural labor, with so many of its men still overseas, saw an opportunity. The prisoners saw a chance to earn small wages and escape the boredom of the huts. Elsa was sent to a dairy farm 3 mi from the camp along with a dozen other women.

They rode in the back of a truck each morning, flanked by a single guard, an older corporal named Davies, who carried a rifle he never pointed, and a thermos of tea he occasionally shared. The farm belonged to a man named Whitmore, 60some, weathered as old leather, who ran the place with his wife and a teenage son. He stood in the yard that first morning, arms crossed, and looked the women over with a gaze that was wary but not hostile.

“You’ll milk,” he said through an interpreter. “Morning and evening, 6 days a week. You break something, you fix it. You steal. You’re gone. You work honest, you’ll eat honest. Simple as that.” The women nodded. They had expected worse. The work was hard. Dawn milking began at 5:00 a.m., fingers aching in the cold, backs bent over wooden stools.

The cows were large and indifferent, occasionally kicking, but the rhythm of it, pull, squeeze, release, was soothing in its simplicity. No radios crackling with bad news, no bombs, just the hiss of milk into pales and the warm grassy smell of the barn. By the second week, Whitmore’s wife began leaving a pot of tea on the workbench along with thick slices of bread.

She said nothing, just set it down and walked away. The women drank it gratefully, hands wrapped around the warm tin mugs. By the third week, Ilsa could milk a cow faster than Whitmore’s son, and he admitted it grudgingly. The work became routine, then competence. Then, quietly, a source of pride.

One afternoon, as Elsa was hauling a pale toward the cooling shed, Whitmore appeared beside her. He took the pale without asking and carried it the rest of the way. When he set it down, he said in slow, careful English, “Good work.” Ilsa, whose English was improving in fragments, nodded. “Thank you.” Whitmore grunted and walked away. But the next morning, there was an extra slice of bread waiting.

And the morning after that, a pat of real butter. Small gestures earned, not given. The currency of respect built one pale of milk at a time. Not all the locals were as pragmatic as Whitmore. Some refused to acknowledge the prisoners at all, turning away when the trucks passed. Others glared with a bitterness that needed no translation. The war had cost Britain dearly.

Families had lost sons, brothers, fathers, cities had burned. Rationing still pinched tight. Resentment was a resource that never ran out. But proximity has a way of eroding certainty. Mrs. Whitmore, who had said nothing to the prisoners for the first month, began to speak in clipped functional sentences. “Mind the gate. Don’t leave tools in the rain.”

Later, when one of the women, a girl named Analisa, caught a fever, Mrs. Whitmore brought her a bowl of soup herself, set it down on the bunk, and left without a word. The next day, Ana returned to work. By winter, small shifts had accumulated into something larger. Elsa was allowed to walk unescorted from the barn to the house when she needed to fetch supplies.

The teenage son, who had once glared at her, now joked in broken German about the cows. And on Christmas Eve, when the women returned to camp after a long day, Whitmore pressed a small parcel into Ilsa’s hands. Inside a scarf, knitted wool, worn but clean. “Wives,” he said gruffly. “Don’t need it now.”

Elsa wanted to say something, but the words tangled. She settled for a nod, clutching the scarf as the truck rattled away. That night, she wore it in the hut, and several women asked where it came from. She told them. They said nothing, but their silence was not empty. It was the silence of people reconsidering the map of the world they had been handed.

Trust, it turned out, was not given in declarations. It was built in gestures so small they barely registered until you looked back and realized the ground had shifted beneath you. In late October, a woman named Margot developed a persistent cough that turned bloody. The camp’s medical officer, a Scottish doctor named Mloud, examined her and diagnosed tuberculosis.

Within hours, she was transferred to a civilian hospital in Canterbury. The women watched her go with rising fear. Hospitals were where people disappeared. But 3 weeks later, Margot returned. Thinner, yes, but alive. She spoke in a dazed voice about clean sheets, medicine that tasted bitter but worked, and a British nurse who had sat with her during the worst night.

Reading aloud from a book Margot couldn’t understand but found comforting anyway. “They treated me,” Margot said, still disbelieving, “like I was a person.” Mloud visited the camp weekly, checking on chronic ailments and dispensing treatment with the same brisk efficiency he would have used on British soldiers. He did not smile often, but he did not sneer either.

When Elsa asked him once why he bothered, he looked at her as though the question itself was absurd. “You’re ill,” he said simply. “I’m a doctor.” It was a statement so plain it felt radical. The numbers supported the sentiment. Medical care for German PS in Britain was comprehensive. Serious cases were transferred to hospitals. Vaccinations were administered.

Dental care, though basic, was provided. The mortality rate among PS from disease remained negligible, a stark contrast to the chaos of some American or French transit camps, where logistics had collapsed under the weight of numbers. Britain had decided that letting prisoners suffer was beneath it. Not because prisoners deserved mercy in some abstract sense, but because a civilized nation did not abandon its standards under pressure. Mloud never said any of this.

He simply treated his patients and moved on. But his actions, repeated week after week, carved out a truth the women could not ignore. The enemy they had been taught to fear was capable of restraint. And restraint, they were learning, was its own form of power. After a particularly brutal shift, a coward kicked over a full pale, and Elsa had to start over in the freezing dawn.

She sat on the edge of her bunk and thought about the last year. The mud, the hunger, the American camps, the sergeant with the tea, the nurse, Whitmore’s gruff, “good work,” Mrs. Whitmore’s scarf. None of it fit the story she had been told. If you’re finding these forgotten corners of history worth your time, consider subscribing. History doesn’t need sensationalism. It just needs listening.

Christmas came with frost that turned the camp’s wire into silver lace. The women had not expected to celebrate. Prisoners did not get holidays, but the British, it seemed, operated differently. On Christmas Eve, the camp commandant, a soft-spoken major named Henshaw, announced that a service would be held in the mess hut.

Attendance was optional. A German-speaking chaplain had been arranged. Ilsa went along with most of the others. The hut had been decorated sparsely. A small pine tree, a string of paper garlands, candles set on the window sills. The chaplain, a thin man with kind eyes, read from the Gospel of Luke in careful German.

The women sang still quietly, voices cracking on the high notes. When the service ended, the guards who had stood respectfully at the back brought in trays, biscuits, chocolate, tinned fruit, small luxuries hoarded from rations. They set them on the tables without ceremony and stepped back. Major Henaw cleared his throat. “Happy Christmas,” he said in accented German.

Then, in English to his men, “at ease,” the guards relaxed. One of them, Private Collins, approached hesitantly and offered Elsa a cigarette. She shook her head. She didn’t smoke, but thanked him anyway. He nodded, embarrassed, and retreated. Later that night, as the women sat in the hut with full stomachs and the faint warmth of human kindness lingering, Jazella said softly, “I didn’t think they would remember we were Christian, too.”

No one answered, but several women nodded. In December, the women were told they could write letters home. The letters would be censored, of course, and delivery was not guaranteed. Germany was fractured, occupied, its postal system a patchwork of chaos. But the offer was made, and most women accepted.

Ilsa sat with a pencil and thin paper trying to find words for her mother. She could not say where she was. That would be censored. She could not describe the farm, the food, the kindness. She did not know if her mother would believe it. In the end, she wrote, “I am alive. I am fed. I am treated fairly. Do not worry. Simple, safe, true.” Her letter, along with dozens of others, passed through the hands of a British sensor, was stamped, and eventually made its way east.

Months later, Elsa would learn that her mother had received it, that it had been read aloud in a neighbor’s kitchen, that the neighbor, whose son was still missing, had wept, and said, “At least someone’s children are safe.” The letters, small and constrained as they were, carried a weight beyond their words. They were evidence, proof that the propaganda had lied, that surrender to the British did not mean death.

In towns across occupied Germany, those letters became quiet arguments against despair. The British, whatever else they were, had kept their prisoners alive, had fed them, had not tortured them. The contrast with Soviet camps, where letters rarely came and conditions were brutal, sharpened the point. One letter could not undo a war.

But multiplied by hundreds, by thousands, they became a chorus that whispered a subversive truth. Restraint was possible. Civilization could survive. By early 1946, routines had solidified. Work, meals, sleep. But within that structure, small freedoms began to emerge.

A camp library was established, stocked with donated books in German and English. Ilsa borrowed a battered copy of Janeire, reading it slowly, dictionary in hand. Others read newspapers, censored but current, or German classics smuggled in by sympathetic chaplain. A music club formed. Women with instruments or memories of instruments gathered twice a week to sing.

Harmonies rose through the hut, filling the cold air with something warmer than blankets. The guards tolerated it. Some even stopped to listen. Language classes began. A handful of British soldiers, bored and curious, offered to teach English in exchange for German lessons. The exchanges were awkward, full of laughter and misprononunciations, but they created a bridge where none had existed before.

One evening, Private Collins sat across from Elsa at a rough wooden table, pointing at words in a primer. “Chair, table, window.” Elsa repeated them carefully. When she got window wrong, he corrected her gently. When she got it right, he grinned. “You’re good at this,” he said. She smiled. “You are patient teacher.”

It was a small moment, insignificant on its face, but it was also two people who had been enemies choosing to sit together and share knowledge. That choice, repeated night after night, was its own form of victory. Not everything was smooth. Discipline was necessary. Rules were broken. One afternoon, a woman named Hilda tried to smuggle extra food from the farm back to camp.

She was caught at the gate, the bread bulging beneath her coat. The guard, a stern sergeant named Morris, confiscated it and reported her. Hilda expected punishment. A beating perhaps, solitary confinement. Instead, she was called to Major Henshaw’s office. He sat behind his desk looking tired. “You stole,” he said flatly.

“I was hungry,” Hilda replied, defiant and ashamed. Henshaw leaned back. “You are fed here. Three meals a day. You know this.” “Not enough, perhaps, but stealing is not permitted. You understand?” Hilda nodded. “You will lose recreation privileges for one week,” Henaw said. “No library, no music club. That is your punishment. If it happens again, the consequences will be more severe.”

Hilda stared. “That’s all.” Henshaw’s gaze was steady. “The barbed wire is the punishment. I don’t need to add more.” It was a philosophy the British guards seemed to share. Confinement was penalty enough. Cruelty on top of it served no purpose.

When a guard lost his temper and shoved a prisoner, he was reprimanded publicly. When another made inappropriate comments, he was reassigned. The message was clear. Discipline was necessary, but brutality was not. The line between the two was carefully maintained. To the women, who had known camps where guards ruled by fear and fists, this restraint was almost incomprehensible. But over time it became the norm.

The wire was real. The rules were real. But within those boundaries, dignity was preserved. And dignity, they were learning, was not a luxury. It was the foundation of everything else. By spring of 1946, something remarkable had happened. The war had been over for nearly a year, but repatriation was slow. Agreements between the Allies and the fractured German zones were tangled.

Logistics lagged. Many prisoners remained in Britain waiting. But waiting had changed shape. Elsa no longer needed an escort to walk from the camp to Whitmore’s farm. She left each morning with the other women unsupervised and returned each evening. The trust was implicit.

If they ran, where would they go? Britain was an island. Germany was rubble. But more than practicality held them. Something quieter had taken root. Routine. Respect. The knowledge that running would betray the small, hard-earned trust that had been built. At the farm, Whitmore now let Elsa operate the tractor during plowing season. It was a significant gesture. Machinery was valuable.

Misuse could be costly. But he handed her the controls with a brief nod and walked away. She drove carefully, feeling the weight of his trust as much as the machine. One afternoon during the summer harvest, the workload became overwhelming. Whitmore was short-handed and a storm threatened.

Without being asked, Elsa and the other women volunteered to stay late, working until dusk to bring the hay in before the rain. They were not paid extra. They simply did it. Whitmore said nothing that night, but the next morning he brought tea to the barn himself and poured it into their mugs.

“Good people,” he muttered, then walked away before anyone could respond. The shift was subtle, but profound. The women were no longer prisoners being supervised. They were laborers being relied upon. They had earned their place, not through pleading or performance, but through competence and consistency. Pride returned. Not the hollow, brittle pride of propaganda, but something quieter, the pride of work done well, of trust honored.

That more than anything marked the final erosion of the old beliefs. Elsa sat on the steps of the hut one evening in late June, watching the light fade over the downs. The air smelled of cut grass and distant rain. She thought about the last year, about the mud and the fear, about the tea on the platform, about Witmore’s scarf and the chaplain’s candles and Mloud’s steady hands.

She thought about the propaganda, the lies that had shaped her understanding of the world. If the British were not monsters, what else had been false? If prisoners could be treated with decency, what did that say about the cause she had once served? The thoughts were dangerous, unsettling, but unavoidable. Years later, when historians interviewed former PWs, Ilsa would be among them.

Her words would be recorded in a transcript filed away in an archive few would read. “I expected cruelty,” she would say. “I had been told the British were brutal, that they would starve us, beat us, use us, and yes, it was a prison. Yes, we were not free. But they did not need to treat us as human. They chose to. And that choice forced me to question everything I had believed. If they could be decent, then perhaps we had not been. That was the hardest truth of all.”

She would pause in the recording, her voice quiet. “The real prison was not the wire. It was the lie I had lived inside.”

The tape would end shortly after, but the truth in those words would linger. Repatriation finally came in the autumn of 1946. The women were processed once more, given documents, and told they could return to Germany. Trains were arranged, camps emptied. Some left immediately, desperate to find family, to rebuild, to go home. Others hesitated.

Ilsa stood in line with her papers and thought about home. Her mother’s letters had been brief. The village was half destroyed. Food was scarce. Work was scarcer. The occupation zones were tangled with bureaucracy and bitterness. Germany was not a home anymore. It was a wound. She thought about Whitmore’s farm, about the rhythm of the work, about the quiet trust that had been built.

When she reached the processing desk, the British officer looked up. “Repatriation or voluntary extension.” “Extension?” She said quietly. He stamped her papers without comment. Not all the women stayed, but some did. They worked through the winter of 1946, earning small wages, sending money home when they could. By 1947, as conditions in Germany stabilized, most returned.

But a few, very few, chose to settle permanently. They married British men or found work in towns that no longer saw them as enemies. Ilsa stayed for another year, then left in the spring of 1947. Whitmore drove her to the station himself. They did not say much. There was not much to say. “Safe journey,” he said, handing her a parcel.

Inside a loaf of bread, fresh and warm. She nodded, unable to speak. Then she boarded the train. Years later, she would write him a letter. He would write back. The correspondence would continue sporadically for decades. Small updates, news of family, a photograph of Ilsa’s children, a postcard from Whitmore’s visit to London.

The war had ended, but the quiet bond it had forged, unlikely and resilient, endured. Civilization is not the absence of conflict. It is the choice made daily to maintain standards when abandoning them would be easier. The British did not have to treat their prisoners with decency. They could have justified cruelty a hundred ways. Revenge, efficiency, indifference. The temptation was real. And in some places, it won.

But in most camps, on most farms, in most encounters, restraint prevailed. Not because it was easy, but because it was chosen. The tea on the platform, the nurse’s steady hands, the chaplain’s candles, the farmer’s trust. Each was a small refusal to let the war strip away what mattered.

The women who lived through it carried that knowledge forward. It changed them in ways they could not articulate, but could not deny. They had expected monsters and found men. They had expected brutality and found order. And that contradiction forced them to reconsider everything. The real victory in the end was not territorial. It was moral.

Britain proved that a nation at war could remain a nation of laws. That power, enormous and unchecked, could still choose restraint. The tin mugs handed out on that railway platform became symbols, not grand or dramatic, but humble, a reminder that decency, when practiced consistently, accumulates into something larger, something that outlasts the war itself. If these stories of restraint and quiet dignity resonate with you, subscribe.

History’s most important lessons are often its quietest. Ilsa kept the mug for decades. It sat on a shelf in her kitchen in a rebuilt German town, dented and tarnished. Visitors sometimes asked about it. She would smile and say “only a gift.” But at night, when the house was quiet, she would hold it in her hands and remember the cold platform, the sergeant’s voice, the warmth spreading through her fingers.

She remembered and she understood. True strength is not in the fist, but in the hand that chooses not to close.

News

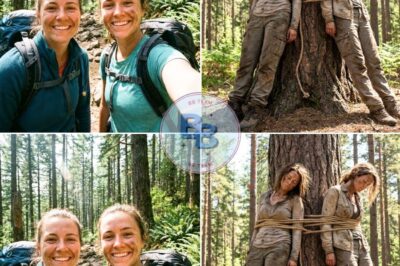

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS In the early autumn…

She Disappeared — 15 Years Later, Son Finds Her Alive in an Attic Locked with Chains.

She Disappeared — 15 Years Later, Son Finds Her Alive in an Attic Locked with Chains. Lucas parked the pickup…

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901)

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901) In the spring…

They Banned His “Boot Knife Tripline” — Until It Silenced 6 Guards in 90 Seconds

They Banned His “Boot Knife Tripline” — Until It Silenced 6 Guards in 90 Seconds At 3:47 a.m. December 14th,…

What Genghis Khan Did to His Slaves Shocked Even His Own Generals

You’re standing in the war tent when the order comes down. The generals fall silent. One of them, a man…

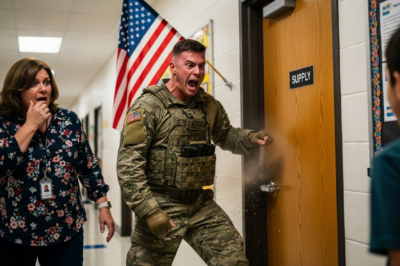

Teacher Locked My 5-Year-Old in a Freezing Shed for Lunch… She Didn’t Know Her Green Beret Dad Was Coming Home Early.

Chapter 1: The Long Way Home The C-130 transport plane touched down on American soil with a screech of tires…

End of content

No more pages to load