There’s a photograph that still exists locked in a vault in Virginia. It shows a child who should not have been possible. A boy born in 1938 to parents who shared the same blood going back 16 generations. The family called him a “miracle.” The doctors called him something else. What they found inside that child’s body would force an entire bloodline to confront a question they’d been avoiding for 200 years.

“What happens when purity becomes a prison?”

This is that story and it’s worse than you think.

Hello everyone. Before we start, make sure to like and subscribe to the channel and leave a comment with where you’re from and what time you’re watching. That way, YouTube will keep showing you stories just like this one.

The Mather family arrived in colonial Virginia in 1649. They were English gentry, minor nobility with land grants and a name that meant something back in London. But America gave them something England never could: control, complete, unchallenged control over who entered their bloodline and who didn’t.

They didn’t call it obsession then. They called it “preservation.” By 1700, the Mathers had established what they referred to in private correspondence as “the covenant.” It was simple. Marry within the family. Keep the land together. Keep the name pure. Keep the blood unmixed. For the first few generations, this wasn’t unusual.

Cousin marriages were common among the colonial elite. But where other families eventually opened their doors, allowed fresh blood, adapted to a changing world, the Mathers doubled down. They built their estate, Ashford Hall, 30 mi from the nearest town. They educated their children at home. They attended a private chapel on their own grounds.

By 1800, they had become a closed circle. And that circle kept tightening. The family kept meticulous records, leatherbound genealogies that tracked every birth, every marriage, every union. They weren’t just preserving history. They were engineering it. First cousins married first cousins. Then second cousins married each other.

Then their children did the same generation after generation. The same names, recycling, Thomas, Elizabeth, William, Margaret. The same faces appearing over and over in daguerreotypes and oil paintings like echoes of echoes of echoes. By 1900, the Mathers weren’t just isolated. They were biologically distinct, a population unto themselves, and they were proud of it.

They believed they had achieved something rare, something sacred. They believed their blood was purer than anyone else’s in Virginia, maybe in all of America. They believed they had protected themselves from the contamination of the outside world. They had no idea what they’d actually done. The first signs appeared in the 1870s, but no one called them warnings.

A daughter born with six fingers on her left hand. A son whose legs bowed so severely he never walked without pain. A stillbirth. Then another, then three in a single year. The family called these things “God’s will.” They held private funerals. They buried the children in the family cemetery behind Ashford Hall under stones that listed no cause of death.

They didn’t write about these losses in letters. They didn’t speak of them to outsiders. And they certainly didn’t stop marrying each other. By 1900, the Mather family tree had become something else entirely. It wasn’t a tree anymore. It was a knot, a tangle of lines that looped back on themselves again and again.

If you tried to map it, you’d see the same names appearing in multiple positions. A man who was simultaneously someone’s uncle, second cousin, and grandfather. A woman who was both aunt and sister-in-law to the same child. The mathematics of kinship had broken down. What remained was something biology was never meant to handle, but the outside world barely noticed.

The Mathers kept to themselves. They were wealthy enough that eccentricity was called tradition. They owned enough land that isolation seemed like choice rather than necessity. When they came to town, which was rare, people remarked on how they all looked alike. The same sharp nose, the same deep set eyes, the same way of holding their heads, tilted slightly back, as if perpetually looking down at something beneath them.

People said they looked “aristocratic, pure.” No one said what they actually looked like. Copies degrading with each generation. Then came 1923. A Mather daughter, Catherine, tried to leave. She was 17. She’d read books smuggled in by a sympathetic tutor. She’d seen photographs of the world beyond the estate.

She wanted to go to Richmond, maybe even further. She told her father she wanted to marry someone from outside the family. Someone new. The conversation lasted 4 minutes. Her father, Thomas Mather VI, made his position clear. If she left, she would be “dead to them.” Her name would be struck from the family Bible. Her face would be removed from the portraits.

She would become a ghost. Catherine stayed. 6 months later, she married her first cousin. His name was also Thomas. Catherine and Thomas had their first child in 1925, a daughter. She lived for 3 days. The second child came in 1927, a son. He survived, but he never spoke. Not a single word in his entire life.

He would sit in the corner of the nursery, rocking back and forth, his eyes fixed on nothing. The family doctor, a man named Harold Brennan, who had served the Mathers for 30 years, wrote in his private journal that the boy seemed “trapped in a place the rest of us cannot see.” The third child was born in 1929, another daughter.

She appeared healthy at first. Then at age 4, she began having seizures, 10, sometimes 15 a day. She died before her 8th birthday, but Catherine and Thomas kept trying because that’s what Mathers did. You produced heirs. You continued the line. By 1935, Catherine had been pregnant seven times. Three children survived past infancy.

None of them were quite right. The family stopped inviting the doctor to holiday gatherings. They stopped hosting the rare visitors who still came to Ashford Hall. The shutters stayed closed. The gates stayed locked. Inside those walls, something was unraveling. Then, in January of 1938, Catherine became pregnant again.

She was 32 years old and exhausted. Her body had been through too much. But this pregnancy was different. She didn’t get sick. She didn’t have the complications that had plagued her other pregnancies. For the first time in years, there was hope. Maybe this child would be the one. Maybe this child would be perfect.

Maybe this child would prove that the covenant had been right all along. The boy was born on September 14th, 1938. They named him William, like his great-great-grandfather and his great-great-great-grandfather. Before that, when Dr. Brennan first saw the infant, he said nothing for a full minute. The nurses who attended the birth were sworn to secrecy.

Catherine held her son and wept, not with joy, with something else, something that didn’t have a name yet, because William Mather was beautiful, unnaturally so. His features were perfect, symmetrical, almost luminous. His eyes were bright and clear. But when Dr. Brennan examined him more closely, away from Catherine’s sight, he found something that made his hands shake as he wrote his notes.

This child wasn’t just unusual. This child was impossible. William’s heart was on the right side of his chest. Not the left where it belonged, but the right. A condition called dextrocardia. Rare, but not unheard of. But that wasn’t all. His liver was on the left. His stomach was reversed.

Every major organ in his body was a mirror image of where it should have been. Complete situs inversus. Dr. Brennan had read about it in medical journals. It occurred in perhaps one in every 10,000 births. But there was more. William had extra bones in his feet, small vestigial things that served no purpose. His skull was slightly misshapen, not enough to see, but enough to feel under careful examination.

There were ridges where there shouldn’t be ridges, gaps that had closed too early or too late. And his blood, when Brennan drew samples, something was wrong with the cellular structure. The red blood cells were malformed. Some too large, others too small. His white blood cell count was abnormal.

His platelets didn’t cluster the way they should. It was as if William’s body had been assembled from a blueprint that had been copied and recopied so many times that errors had crept into every system. But the child lived. He breathed. He cried. He fed. And as the weeks passed, he began to grow. The family celebrated quietly. They told themselves that William’s differences were merely “curiosities.”

After all, he was alive. He was a Mather. He would carry on the name. Dr. Brennan said nothing to contradict them. But in his journal, he wrote, “I have delivered a child who should not exist. I do not know if he is a miracle or a warning.” By the time William was 6 months old, other things became apparent.

He didn’t respond to sound the way other infants did. Loud noises didn’t startle him. Music didn’t soothe him. At first, they thought he might be deaf, but he wasn’t. He could hear. He simply didn’t react. His eyes tracked movement, but there was something absent in his gaze, something that should have been there, but wasn’t.

When Catherine held him, he didn’t mold to her body the way babies do. He remained stiff, distant, as if he were somewhere else entirely. The family began to whisper. Late at night in rooms where servants couldn’t hear, they began to ask the question they’d been avoiding for a century and a half. “What have we done?” William turned 2 years old in 1940.

He still hadn’t spoken. He walked, but with an odd shuffling gait, as if his legs didn’t quite belong to him. He didn’t play with toys. He didn’t laugh. He would spend hours staring at the wallpaper in the drawing room, tracing the patterns with his eyes over and over and over. The other children in the house, his older siblings, avoided him, not out of cruelty, but out of instinct.

There was something about William that made them uneasy, something they couldn’t name. Dr. Brennan came less frequently now. He was 73 years old, and his hands trembled when he held his stethoscope. But in the spring of 1941, Catherine insisted he come to examine William again. The boy had begun doing something new, something that frightened her.

He would stand in front of the mirror in the hallway and stare at his reflection for hours. Not playing, not making faces, just staring. And sometimes late at night, she would hear him in his room talking. Not words exactly, more like sounds, rhythmic, repetitive, like a language that had no human origin. Brennan arrived on a cold afternoon in March.

He found William in the library, sitting perfectly still in a chair far too large for him. The boy’s eyes were open but unfocused. Brennan spoke to him. No response. He clapped his hands near William’s ear. Nothing. He placed a hand on the boy’s shoulder and William’s head turned slowly mechanically until their eyes met. Brennan would later write that in that moment.

He felt as if he were looking at something that was looking back through William, not from him, something that was using the boy’s eyes as windows. The examination took an hour. Brennan measured. He listened. He tested reflexes. And then he did something he’d never done in 50 years of practicing medicine. He asked the family to leave the room.

When they were alone, Brennan sat down across from William and spoke to him as if he were an adult. He said, “I don’t know what you are, but I know you’re not what they think you are.” William’s expression didn’t change. But his lips moved. And for the first time in his life, William Mather spoke. One word, clear, precise, unmistakable.

He said, “Neither.”

If you’re still watching, you’re already braver than most. Tell us in the comments what would you have done if this was your bloodline.

Dr. Brennan left Ashford Hall that evening and never returned. He wrote one final entry in his journal dated March 18th, 1941. It read, “There are some things medicine cannot explain. There are some outcomes that science predicted, but humanity refused to believe. The Mathers have created something that exists in the space between what we are and what we were never meant to become. I have recommended they seek help beyond my capabilities. I do not believe they will.”

He died 4 months later. Heart failure. The journal was found in his desk drawer, locked away with his will. His daughter burned it after reading only three pages. She told no one what she’d seen written there. The family did not seek help. Instead, they made a decision. William would be kept at home. He would be educated privately.

He would be protected from the outside world, just as the family had always been protected. They convinced themselves this was kindness. But it was fear. Fear of what doctors might say. Fear of what the world might think. Fear of what William himself might reveal about what 16 generations of the covenant had produced.

So the boy grew up in silence, in isolation, in a house that had become a tomb for a bloodline that refused to die. As William aged, the physical abnormalities became more pronounced. By age 10, his spine had begun to curve in ways that defied normal scoliosis. His joints were hyper-mobile, bending at angles that made servants look away.

His teeth came in crooked, overcrowded, some growing behind others. But his mind, his mind was the true mystery. He taught himself to read by age five, though no one had instructed him. He could do complex mathematics in his head. He spoke when he chose to speak in perfectly constructed sentences that sounded like they’d been rehearsed for weeks.

But he had no empathy, no emotional connection. He would watch his mother cry and tilt his head like a bird observing an insect. By 1950, the family had shrunk. Catherine died in childbirth attempting one last pregnancy. Thomas drank himself to death 2 years later. The surviving siblings scattered, some to other parts of Virginia, others further away, desperate to escape Ashford Hall and everything it represented.

William remained alone, except for two elderly servants who were paid enough to stay silent. The estate fell into disrepair. Paint peeled. Gardens went wild. The gates rusted shut. And inside, William Mather lived in the decaying monument to his family’s obsession. A living artifact of what happens when purity becomes pathology. William Mather lived until 1993.

55 years old. He never married, never left the estate, never had children. The Mather line, that unbroken chain stretching back to 1649, ended with him. When the county finally sent someone to check on the property after years of unpaid taxes, they found him in the library dead in the same chair where Dr. Brennan had examined him half a century earlier.

The autopsy revealed what the family had spent generations refusing to see. William’s organs were failing, had been failing for years. His kidneys were malformed. His liver was scarred. His heart, reversed though it was, had chambers that didn’t close properly. He had tumors in places tumors rarely grow. His bones were brittle, riddled with micro fractures.

Genetically, the medical examiner wrote, “William Mather had the biological profile of someone whose parents were more closely related than first cousins, closer than siblings.” The DNA analysis showed something that shouldn’t exist outside of laboratory experiments: homozygosity at a level incompatible with long-term survival. The estate was sold.

Ashford Hall was torn down in 1997. Developers built a subdivision on the land. Families moved in. Children play in yards where the Mather Cemetery once stood. The headstones were relocated to a municipal graveyard. No historical marker was erected. No plaque explains what happened there. The Mather Family Bible with its 16 generations of carefully recorded marriages was donated to a university archive.

It sits in a climate controlled vault available to researchers by appointment. Almost no one requests to see it, but the medical records remained. Dr. Brennan’s journal or what survived of it eventually made its way to a medical historian in 2008. She published a paper about the Mathers, changing their name, altering identifying details, but keeping the essential truth intact.

It became a case study, a warning, evidence of what geneticists had been saying for decades. That inbreeding depression isn’t just a theory that genetic load accumulates. That recessive alleles, harmless when paired with healthy genes, become devastating when they have nowhere else to go. That families who close themselves off don’t preserve purity, they concentrate damage.

The paper estimated that by the 16th generation, William Mather’s coefficient of inbreeding was approximately .39. For context, the child of full siblings has a coefficient of .25. William’s parents weren’t just related. They were the product of a genetic bottleneck so severe that William himself was essentially the offspring of what genomics would classify as a single ancestral individual replicated and recombined until the copies broke down.

He wasn’t an individual. He was an endpoint. There’s a question people ask when they hear this story. They ask, “How could they not know? How could an entire family, educated people, wealthy people, people with access to doctors and books, and the outside world not understand what they were doing?” But they did know.

On some level, they always knew. The stillbirths told them. The deformities told them. The children who didn’t speak, who seized, who died young, they all told them. But knowing and accepting are different things. The Mathers chose their bloodline over their children. They chose tradition over survival.

They chose the idea of purity over the reality of what purity costs. William Mather’s photograph still exists. It’s in that university archive attached to the family Bible. He’s 12 years old in the picture, standing in front of Ashford Hall in a suit that’s too large for him. His face is pale, beautiful in that uncanny way. His eyes stare directly at the camera.

And if you look long enough, you start to feel what Dr. Brennan felt. That you’re not looking at a person. You’re looking at the final page of a book that should never have been written. A story that ended the only way it could, with silence, with decay, with a bloodline so pure it poisoned itself. The Mathers believed they were protecting something sacred.

What they actually protected was a genetic time bomb. And William was the explosion. The last Mather, the end of 16 generations. The child no one could explain because explaining him meant admitting what the family had done to itself. And some truths are too terrible to speak out loud, even when they’re staring back at you from a mirror.

Even when they’re written in your blood.

News

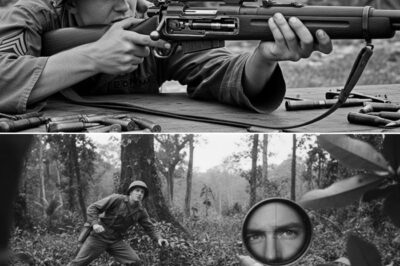

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese…

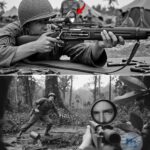

Overwatch in the Rain: How One Army Sniper Opened a Corridor for a SEAL Team

Rain hammers the tin of a joint task force forward base while generators hum and diesel clings to the air….

Do You Know Who I Am? A Marine Shoved Her at the Bar — Not Knowing She Commanded the Navy SEALs

“Women like you get good men killed out here.” The words slammed into Commander Thalia Renwit like a fist as…

Captain Poured Coke on Her Head as a Joke — Not Knowing She Was the Admiral

“You look like you could use a shower, sweetheart.” Captain Derek Holland thought it was funny when he dumped the…

Recruits Aimed A Rifle at Her Skull – They Learned Why You Don’t Provoke A Combat Vet

“I’m a Navy Seal, sweetheart. I’ve forgotten more about combat than you’ll ever learn.” Commander Jason Milner didn’t say it…

I Can’t Close My Legs,” Little Girl Told Bikers — What Happened Next Made the Whole Town Go Silent

From the very first moment, something felt wrong in that quiet motorcycle workshop on the edge of a forgotten American…

End of content

No more pages to load