You’re standing in the war tent when the order comes down. The generals fall silent. One of them, a man who has burned cities without flinching, looks at the con and asks him to repeat it. He does. The words hang in the air like smoke from a funeral p. You glance around. Even the most hardened warriors. Men whose hands are stained with the blood of a hundred battles exchange looks that say the same thing.

This isn’t war. This is something else entirely. Before we go any deeper, drop a comment and let me know where in the world you’re watching from. It never stops amazing. Me that a decision made in a Mongol camp 8 centuries ago can reach someone on their phone today, half a planet away. The year is 1206. The steps of Central Asia have just witnessed the unification of waring tribes under one man.

Teu Jen, now known to history as Genghask Khan, his empire would become the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever seen. Stretching from the Pacific to the Mediterranean. But what truly set him apart wasn’t just conquest. It was how he rewrote the rules of power itself, especially regarding the people at the very bottom, the slaves, the captives, the ones everyone else treated as less than human.

What he did with them didn’t just shock his generals. It violated every assumption about how conquerors were supposed to behave. And the ripples of those decisions would echo through seven centuries of history documented in Persian chronicles, Chinese records, and the terrified letters of European monks who heard the rumors and thought the world was ending.

This is that story, not the sanitized version, the real one. In the autumn of 1206, shortly after his coronation as great Khan, Genghask Khan issued an order that made even his closest advisers pause. He had just returned from a brutal campaign against the Tatters, the same tribe that had murdered his father decades earlier. Thousands of Tat warriors laid dead.

Their families had been captured. Tradition was clear. The men would be executed, the women and children enslaved, distributed among the officers as spoils of war, property, tools. That’s what captives were. Genghask Khan called a kurill tai a gathering of his inner circle. His generals expected rewards, land, titles, slaves to work their new estates.

What they got instead was a speech that turned the logic of conquest inside out. “These people,” he said, gesturing to the thousands of tatter captives huddled under guard, “are not your property. They are mine, and I will decide their fate.” The tent erupted, not in celebration and confusion. What was the point of conquest if not plunder? Then came the second shock.

“The children,” Genghaskhan continued, “will be adopted into Mongol families, not as servants, as sons and daughters. They will be given Mongol names, taught to ride and shoot, and raised as warriors. The women will not be concubines. They will be wives with the same rights as any Mongol woman. The men who surrender will not be changed. They will be soldiers in my army with the same pay and the same share of future plunder as any man-born Mongol.”

Silence. The kind that feels like the moment before a storm breaks. One General Jamuka’s former lieutenant, a man who had fought alongside the Khan for years, stood up. “My Khan,” he said carefully, “if we do not enslave our enemies, how will they know they have been defeated?” Genghask Khan’s reply was recorded by the Persian historian Rasheed Alden, who had access to Mongol court records decades later.

The Khan said something that sounded less like a military strategy and more like a revolution. “A man in chains is worthless. A man who fights for me because I gave him a future is worth a thousand slaves.” It wasn’t mercy. Don’t mistake it for that. Genghask Khan was one of the most ruthless conquerors in human history.

Cities that resisted were annihilated so completely that even their irrigation systems were destroyed, turning farmland into desert. But he had seen something others hadn’t. Slavery was inefficient. A resentful captive was a weak link. But a former enemy who believed he could rise through merit, that was a weapon.

Still, the generals were skeptical. They had lived their entire lives in a world where social status was fixed at birth. Nobles remained nobles. Slaves remained slaves. Mongols remained Mongols. What the Khan was proposing was social chaos. He gave them a demonstration. Among the tatter captives was a boy perhaps 10 years old named Shikiquk.

His parents had been killed in the fighting. By the laws of the step he should have been sold or worked to death. Instead, Genghis Kong brought him into his own gear, his household, not as a servant, as a foster son. The generals watched, waiting for the moment when the boy would be quietly sent away to do menial labor. had never came.

Shigi Coutuk was taught to read and write an unusual skill even among Mongol nobility. He was trained in law, administration, and combat. And within a decade, Genghask Khan appointed him as one of the empire’s supreme judges, responsible for codifying Mongol law. A former slave child became one of the most powerful legal minds in the empire.

The message was unmistakable. But the real shock, the thing that made even the loyal generals question whether their Khan had gone mad came during the campaign against a Quorasmian Empire in 1219. The Quorasmian Sha had made the fatal mistake of executing Mongol envoys. In response, Genghask Khan unleashed a campaign of such calculated terror that chronicers struggled to describe it.

The city of Nishapur was erased. Every living thing inside its walls was killed, including dogs and cats. Bakara was burned. Samuran fell after a siege that left pyramids of skulls outside its gates. Hundreds of thousands of captives were taken. Skilled artisans, engineers, scribes, people with knowledge the Mongols needed.

Standard practice would have been to enslave them. shackle them, force them to work under threat of death. Genghask Khan did something else. He made them an offer. The offer was recorded in the Jaime Al Tawarak, the most comprehensive Persian chronicle of the Mongol Empire. The Khan gathered the captive craftsman and scholars in a field outside Samaran.

Through interpreters, he told them this: “You can return to your homes and rebuild what was destroyed under Mongol rule, paying tribute, always knowing we can return. Or you can join us. You will not be slaves. You will be paid. You will keep your faith. You will teach our children your skills. And if you prove loyal, you will be given land and titles that no conqueror would ever grant a captive.”

The crowd didn’t believe him. Why would they? Every conqueror in history had lied to captives. Promises made before shackles. Then he did something unprecedented. He released a hundred of them. No guards, no chains, just released them with supplies and horses and told them to go tell others what they had heard to test whether he meant it. Most of them ran. A few stayed.

And when the ones who ran reached other cities, they carried a message that sounded like a rumor, a fairy tale, a trap. “The Mongols are freeing skilled captives and paying them.” Within a year, artisans from across Central Asia were voluntarily seeking out Mongol administrators, offering their services. Not because they love the Mongols, how could they after the slaughter, but because the alternative was a lifetime of servitude under local warlords who viewed them as disposable.

Genghask Khan had discovered something terrifying. Freedom, even limited freedom, was a more powerful tool of empire than chains. His generals hated it. There’s a recorded incident from 1222 and documented by the Chinese diplomat Xiao Hung who was sent to observe the Mongol court. A senior general named Mukalli confronted Genghask Khan in front of the assembled commanders.

The argument was over a group of captured Chinese engineers who had been offered positions as siege specialists complete with pay, rank, and the promise that their families would be protected. Mikalli’s complaint was blunt. “These men helped defend the cities we destroyed. They killed our soldiers. Now you want to reward them.”

Genghask Khan’s response was even more blunt. “Do you want revenge or do you want to win?” Mukalli, to his credit, understood, but not everyone did. Some generals began quietly executing captives anyway, out of sight of the Khan, trying to maintain the old order. When Genghdis Khan found out, he made an example that sent a chill through the officer cores.

The general responsible, a man named Belgatai, a distant cousin of the Khan, was stripped of his command and forced to serve as a common soldier for a full year. not executed, not exiled, demoted. The message was clear in this army. My word is law. And I said, “These people are not slaves.” But here’s the darker twist.

The thing that complicates the entire narrative. Genghaskhan’s system wasn’t universal. He freed skilled captives and integrated tribes that surrendered. But cities that resisted, populations that defied him after being warned, they were shown no mercy. Mass executions. Enslavement of the survivors in Termes.

After a brutal siege, tens of thousands were enslaved and distributed among the troops in the traditional way as property. So what was the logic? Why free some and chain others? The answer lies in a single Mongol word, eklas, loyalty. In the Mongol worldview, resistance was betrayal. Surrender was wisdom.

If you surrendered, you could be trusted. If you resisted and lost, you were an enemy forever. This wasn’t moral philosophy. It was cold calculation. Genghis Khan built an empire where former enemies could rise to the highest ranks, but only if they submitted completely. The Chinese general Guo Khan, whose family had fought against the Mongols, became one of the empire’s most successful commanders.

The Persian administrator Adamolik Juveni, whose city had been sacked, ended up governing much of the Western Empire. But the ones who resisted to the end, the historical records are silent on them because they didn’t survive to be recorded. The paradox shattered the minds of observers. How could the same ruler be so ruthless and so generous? How could the same army that built pyramids of skulls also elevate former slaves to positions of power? A Franciscan monk named John of Plano Carpini sent to the Mongol court in the 1240s. He wrote in his report to the Pope:

“They destroy without mercy, yet they reward loyalty as no Christian king does. I do not understand them. I am not sure they are entirely human.” The consequences rippled outward in ways Genghask Khan himself may not have foreseen. By the time of his death in 1227, the Mongol Empire’s administration was filled with men and women who had started as captives.

The empire’s legal code, the Yasa, was maintained and interpreted by former slaves who had been educated in Mongol law. The siege engines that would eventually crack the walls of Baghdad and Kiev were designed and operated by Chinese and Persian engineers who had been given the choice between death and employment.

In Hungary in 1241, Mongol armies arrived with soldiers who spoke a dozen languages because the army had absorbed so many different peoples. European chronicers reported with horror that Christians fought alongside Mongols. Not because they had converted, but because they had been integrated. The Mongol Empire became a machine that devoured enemies and turned them into components of itself.

And at the center of that machine was a principle that violated every rule of medieval society. Status is earned, not inherited. It wasn’t equality. The Mongol aristocracy remained at the top, but it was mobility. A captive could become a soldier. A soldier could become a captain. A captain could become a governor.

The only requirement was ichklas, loyalty. After Genghis Khan’s death, his successors, Guyodi, Gekk, Mongji, Kubla maintained the system. They didn’t reinvent it, didn’t soften it, didn’t question it. They simply continued a strategy that had already reshaped the map of the world. The Yuan dynasty in China was administered largely by non-Mongs, men who had once been outsiders and in some cases enemies.

The Ilanate in Persia was run by Persian bureaucrats who had started as captives and prisoners of war yet became indispensable to Mongol rule. The Golden Horde in Russia incorporated Slavic soldiers into its ranks, turning former hostages into warriors whose loyalty was forged not by birth, but by opportunity. But there’s a final haunting detail that survived in the Mongol Chronicles.

Something that shifts the entire story into a stranger place, a place where power and philosophy blend. It arrives quietly, almost like an afterthought, but it carries the weight of a dying empire builder’s final reflection. In 1226, a year before his death, Genghask Khan returned to Mongolia for the last time. He was aging, tired.

The endless campaigns had worn him down, not only in body, but in spirit. He had seen more cities fall than any man alive. He had watched more armies break. He had buried more friends, rivals, wives, and children than any ruler ever hopes to endure. According to the secret history of the Mongols, the closest thing we have to a Mongol primary source.

He gathered his sons and generals and told them something that confused them. He said, “I have taken more slaves than any man in history, and I have freed more slaves than any man in history.” One day people will remember only one of those things. Choose which one. The room was silent. No one knew how to answer. Was it a test, a confession, a warning, or was it simply the truth spoken plainly by a man who understood that memory, the memory of nations, is a battlefield just like any other. We still don’t know.

What we do know is this. Genghask Khan’s treatment of captives created an empire that lasted longer and integrated more cultures than almost any other in history. It also created a system that was ruthlessly efficient, capable of both extraordinary brutality and extraordinary opportunity. He didn’t abolish slavery.

He weaponized freedom, turning it into a strategic tool rather than a moral principle. And in doing so, he revealed something uncomfortable about power. Mercy and cruelty are not opposites. They are tools and in the hands of a conqueror who understood human nature as deeply as Genghask Khan did. Both could be used to build an empire that stretched across continents, stitched together by roads, messengers, soldiers, and former captives who owed their new lives to the man who had once held their fate on the blade of a sword.

His generals were shocked because they had been taught that conquest meant domination. Conquest meant burning cities, breaking enemies, and taking spoils. But Genghask Khan taught them something far stranger. Conquest meant transformation. You don’t just take territory. You take people. And if you’re smart, if you’re pragmatic, if you’re willing to see beyond tradition, you give them a reason to fight for you instead of against you.

The slaves he freed became the soldiers who terrified Europe. The captives he spared became the administrators who ran an empire so vast that no one before or since has matched it. And the generals who questioned him watched in the decades after his death as his gamble paid off again and again. Every victory, every expansion, every diplomatic exchange with lands thousands of miles away was built on this single paradoxical idea.

But the pyramids of skulls remained too. The cities that never rose again, the populations that vanished from history. There were entire civilizations whose last entries in their chronicles describe the sound of hoof beatats and the smell of burning walls. Two legacies, one man. Both true. The Mongols kept records.

The conquered kept records. And 800 years later, we’re still trying to reconcile the man who freed slaves with the man who destroyed civilizations. Maybe that’s the real shock. Not what he did, but that he could be both. That history allows such contradictions. That power produces them. The scribes wrote it down.

The witnesses told their children. The echo carried through centuries. And now in a language Genghask Khan never heard in a medium he couldn’t have imagined the question still lingers like smoke over a burned city. If you had stood in that tent in 1206 when the order came down would you have believed him? Would you have believed that a conqueror could genuinely see value in elevating his captives? Or would you have thought like his generals that no conqueror could mean what he said? The answer matters because the ones who believed him built an empire and the ones who doubted him became footnotes names buried deep in chronicles. Their skepticism preserved only long enough to remind us that not everyone could understand the scale of the transformation unfolding around them. And maybe that’s the last irony. Genas Khan, a man often remembered for destruction, understood creation just as deeply.

Not the creation of peace or compassion, as we might imagine, but the creation of systems, alliances, and loyalties. The creation of a world where former slaves could become commanders, where former enemies could administer provinces, where the line between captive and citizen blurred until it became a strategy instead of a sentence in the end.

Maybe his final message wasn’t meant to be solved. Maybe it was a mirror one reflecting the truth that power is always a dualged blade and the hand that wields it decides which edge cuts deeper. But the world remembers both. It always does.

News

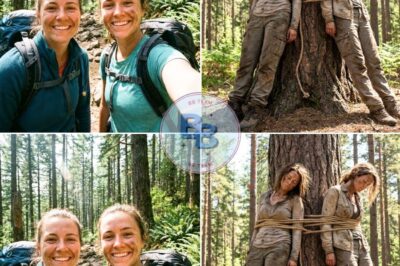

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS In the early autumn…

She Disappeared — 15 Years Later, Son Finds Her Alive in an Attic Locked with Chains.

She Disappeared — 15 Years Later, Son Finds Her Alive in an Attic Locked with Chains. Lucas parked the pickup…

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901)

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901) In the spring…

They Banned His “Boot Knife Tripline” — Until It Silenced 6 Guards in 90 Seconds

They Banned His “Boot Knife Tripline” — Until It Silenced 6 Guards in 90 Seconds At 3:47 a.m. December 14th,…

“You’re Mine Now,” Said The British Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved For Days

“You’re Mine Now,” Said The British Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved For Days September 1945, 1430 hours. A…

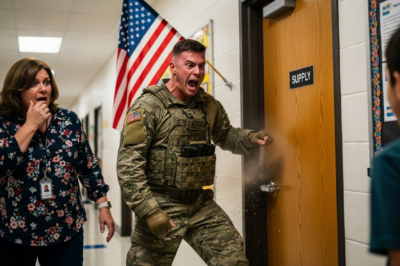

Teacher Locked My 5-Year-Old in a Freezing Shed for Lunch… She Didn’t Know Her Green Beret Dad Was Coming Home Early.

Chapter 1: The Long Way Home The C-130 transport plane touched down on American soil with a screech of tires…

End of content

No more pages to load