Veterinarian Vanishes in 1987 — Three Years Later, Police Make a Macabre Discovery at a Slaughterhouse.

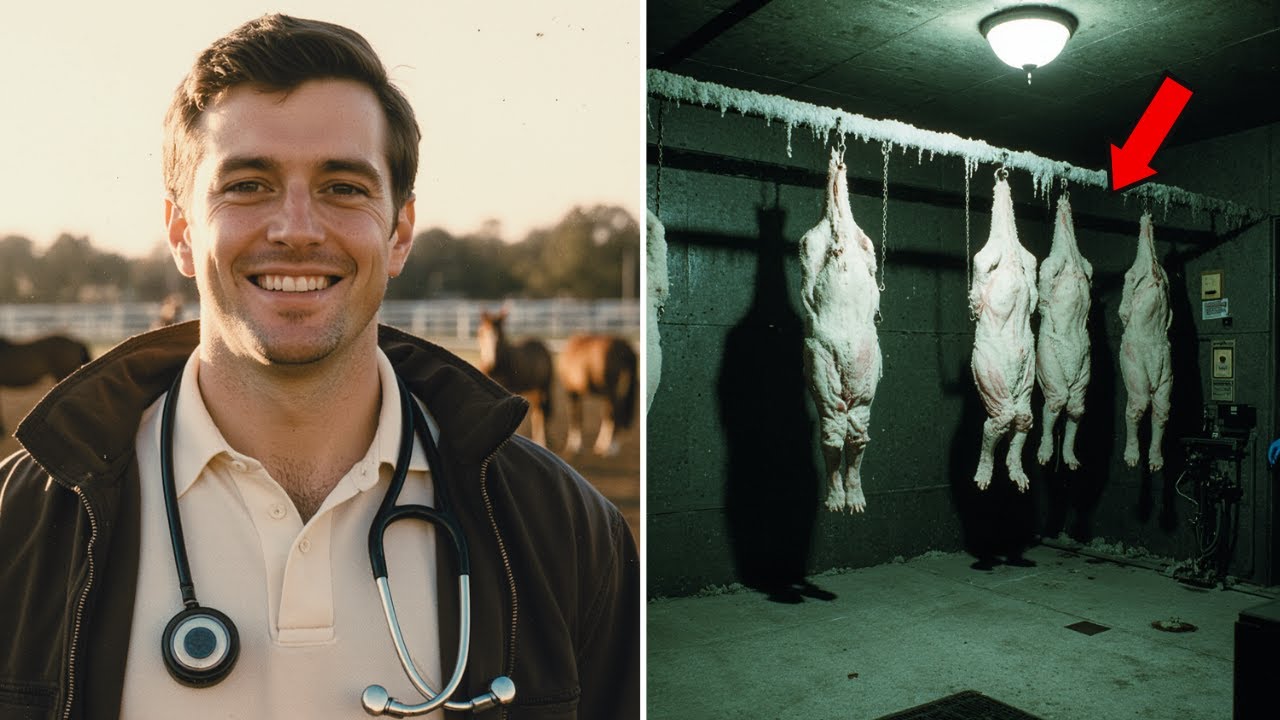

Dr. Thomas Brennon was 34 years old and considered one of the best racehorse veterinarians in the state. He worked at the prestigious Churchill Downs, Kentucky’s most famous racetrack, where the Derby had been held every year since 1875. On that cold March morning, Thomas parked his blue Ford truck in the employee lot, as he had done every morning for 8 years.

He greeted the security guard at the entrance, grabbed his usual coffee at the canteen, and headed to the stables.

“Good morning, Doc,” called Marcos Web, one of the oldest grooms. “Need you to take a look at Thunder Road. He’s limping on his left hind leg.”

Thomas nodded, grabbing his medical bag. Thunder Road was a 3-year-old stallion valued at over 2 million dollars. Any injury could mean the end of his career before it even began. While examining the animal, Thomas talked to Marcos about the approaching season.

“This horse has potential for the Derby,” he said, carefully palpating the tendon. “But he needs rest, no training for two weeks.”

“The owner won’t like that,” Marcos murmured.

“The owner can call me if he has a problem with my professional evaluation.”

That was one of the things everyone respected about Thomas. He never compromised the animals’ health for money or pressure. In a sport where millions of dollars changed hands in bets, such integrity was rare.

At 2:00 PM, Thomas received a strange call. It was from a number he didn’t recognize.

“Dr. Brennon, I need you to come to Sullivan Slaughterhouse immediately. We have an emergency situation with some horses.”

Thomas frowned.

“Sullivan Slaughterhouse? I don’t work with slaughter—”

“Please, doctor. These are retired racehorses. I need someone who understands the breed. I will pay double your normal rate.”

Against his better judgment, Thomas agreed. The Sullivan Slaughterhouse was 40 km from Louisville, in the rural areas of Kentucky. It was a place that mainly processed cattle, but occasionally dealt with old or injured horses that owners no longer wanted to keep. Thomas hated that aspect of the industry—horses that had raced, that had won prizes, ending up on a slaughter line—but it was the brutal reality of the business.

He told Marcos where he was going and left in his truck around 3:30 PM. The sky was gray, threatening rain. The rural road was deserted, surrounded by farms and empty fields.

When Thomas didn’t return home that night, his wife Sarah initially didn’t worry much. He sometimes stayed late when there were emergencies with the horses. But when midnight arrived and he didn’t answer the phone, she started calling the racetrack.

“No, Mrs. Brennon,” the night security guard said. “Dr. Brennon left around 3:30 in the afternoon. Marcos said he was going to check something at a slaughterhouse.”

Sarah called the police at 2:00 AM. Sheriff Daniel Cooper took the case personally. Thomas Brennon was known in the community: a man of integrity, a good father to two young children, with no history of trouble.

They found Thomas’s truck the next day, abandoned on a dirt road 5 km from Sullivan Slaughterhouse. The keys were still in the ignition. His medical bag was on the passenger seat. No sign of struggle, no sign of Thomas.

Sheriff Cooper went to Sullivan Slaughterhouse. The owner, Robert Sullivan, was a large 55-year-old man with hands the size of hams and a permanently scowling expression.

“Veterinarian? I didn’t call any veterinarian,” Sullivan said, spitting tobacco on the ground. “We don’t have horses here right now. Only cattle!”

“Someone called Dr. Brennon from your slaughterhouse, asking him to come. It wasn’t me, and I don’t have a phone in the office—it’s been broken for a week. The phone company still hasn’t come to fix it.”

Cooper checked. It was true. The slaughterhouse phone had been disconnected for eight days. Whoever had called Thomas, it wasn’t from there.

“Can I take a look around the premises?” Cooper asked.

Sullivan shrugged. “Be my guest, but you won’t find anything. I don’t know about any veterinarian.”

Cooper spent two hours inspecting the slaughterhouse. It was a sinister place, the smell of blood and death impregnated in the concrete walls, hooks hanging from rails on the ceiling, the drainage floor stained by decades of blood, but nothing that indicated a crime, nothing related to Thomas Brennon.

The investigation continued for weeks. They interviewed everyone at the racetrack, checked Thomas’s finances—nothing suspicious. His marital life was stable, he had no known enemies. There was no reason for him to simply disappear. The official theory was kidnapping followed by murder, probably for money. Racehorse veterinarians sometimes carried expensive drugs, but no body was found, no ransom demand, nothing.

Sarah Brennon appeared on local television, pleading for information.

“Please, if anyone knows anything about my husband, anything at all, contact the police. Our children need their father. I need to know what happened.”

But days turned into weeks, weeks turned into months. The case went cold. Other crimes demanded attention. Life went on. Thomas Brennon was officially declared presumed dead in 1989, 2 years after his disappearance. Sarah received the life insurance and tried to rebuild her life with her two young children.

The Sullivan Slaughterhouse continued operating normally. Robert Sullivan processed cattle, paid his taxes, and stayed out of trouble. In everyone’s eyes, he was just a rural businessman doing his dirty but necessary job. No one knew that in the sub-basement of that blood-stained concrete building, there was a compartment that didn’t appear on any blueprint of the building, a cold and dark space where secrets were kept, where the truth about Dr. Thomas Brennon waited, frozen in time, and no one would know.

Until three years later, during a routine inspection that should have been simple, federal inspectors began asking questions about inconsistencies in the weight records of processed meat. Questions that would lead to a discovery that would horrify the entire nation.

Margaret Chen was 28 years old and a federal inspector for the USDA, the United States Department of Agriculture. Her job was to inspect meat processing establishments, ensuring compliance with health and food safety regulations. It was a job most people found repugnant. Margaret didn’t mind. She had grown up on a farm in Iowa. She had seen animals born and die. She wasn’t sentimental about the process, but she was meticulous, obsessed with details. And that was what led her to Sullivan Slaughterhouse on that hot June morning.

“There are discrepancies in your records, Mr. Sullivan,” Margaret said, flipping through papers on her clipboard. “In the last six months, you reported processing 847 heads of cattle, but your purchase records show only 720 animals acquired.”

Robert Sullivan was sitting behind his messy desk, his red face shining with sweat.

“Accounting errors. My accountant is an idiot.”

“A 127-head difference is not an accounting error, Mr. Sullivan. It’s federal fraud.”

“Look here, miss…”

“It’s Inspector Chen, and I will need to perform a full inspection of the facilities, including all cold storage chambers, storage areas, and temperature logs.”

Sullivan stood up, trying to use his size to intimidate.

“You can’t just come in here and—”

“I can, actually. It is in the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 9, Section 301.2. I can inspect any area of this establishment without prior notice. If you refuse cooperation, I can shut down your operations immediately.”

Margaret didn’t blink. She had dealt with men trying to intimidate her since she started this job. She was 1.60 meters tall and weighed 52 kg, but she had the authority of the federal government and wasn’t afraid to use it.

Sullivan finally sat down. “Do your inspection.”

Margaret spent the next 4 hours at the slaughterhouse. She checked the slaughter area—adequate, though not impeccably clean. She checked the cold chambers where carcasses hung from hooks—temperatures correct, storage acceptable. She checked the processing room where meat was cut and packaged. She checked temperature logs, cleaning logs, employee certificates. Everything seemed to be in order, except for the numbers that didn’t add up.

“Mr. Sullivan, where exactly do you store the meat that isn’t in the main cold chambers?”

“I don’t have other storage.”

“Your electrical records show consumption consistent with at least two additional refrigeration units besides the ones I saw.”

Sullivan blinked. It was quick, but Margaret noticed. Nervousness.

“Old equipment. It’s not always running.”

“Can I see it?”

“There’s nothing to see.”

“Then you won’t mind if I look.”

It wasn’t a question. Margaret was already walking, checking doors, hallways, storage areas. Sullivan followed her, increasingly agitated.

“You don’t have a warrant for—”

“I don’t need a warrant. We’ve already established that.”

Margaret found a door at the end of a dimly lit corridor. It was locked.

“Where does this door lead?”

“Old basement. We don’t use it anymore.”

“Why is it locked?”

“To avoid accidents. Stairs are bad.”

“Open it.”

“I don’t have the key here.”

Margaret looked at him with an expression that clearly said she didn’t believe him.

“Mr. Sullivan, I can come back with a federal marshal and a court order, or you can open this door now. Your choice.”

There was a long silence. Margaret could see Sullivan calculating options. Finally, he sighed and took a set of keys from his pocket.

“Stairs are bad,” he repeated. “If you get hurt…”

“I’ve noted your concern.”

The door opened with a creak. Cold, damp air rose from the stairs leading down into darkness. Margaret turned on her flashlight and descended carefully. The basement was larger than she expected. Low concrete ceiling, walls stained with dampness, several old boxes piled up, obsolete equipment covered in dust. And at the back, partially hidden behind metal shelves, there was a heavy metal door with an industrial latch, the type of door used in cold storage chambers.

“What is that?” Margaret asked.

“Old freezer. Hasn’t worked in years.”

Margaret approached, placed her hand on the door; it was freezing.

“I feel cold coming from here. It is working, Mr. Sullivan. Must be a refrigerant leak or something.”

Margaret tried the latch; locked.

“Open it.”

“I don’t have the key, Mr. Sullivan.”

Margaret turned to face him. “For the last time. Open this door now.”

There was something in her voice, an absolute authority that admitted no refusal. Sullivan realized he had no choice left. If he refused now, she would return with reinforcements. It would be worse. With trembling hands, he looked for another key on the ring.

“Look, there are things in there that aren’t for human consumption. Old carcasses I should have discarded, but I didn’t. It’s illegal, I know, but it’s not…”

“Open the door.”

The latch clicked. Sullivan pulled the heavy door. Icy air rushed out, forming mist. Margaret pointed her flashlight inside, and what she saw would make this the most famous inspection in USDA history.

Margaret Chen had seen many unpleasant things in her three years as a federal inspector. Rotting carcasses, rat infestations, disgusting sanitary conditions—but nothing had prepared her for what her flashlight illuminated in that underground cold chamber. Hanging on meat hooks along the walls were bodies. Not cattle. Humans.

Margaret let out a sound that was half scream, half gasp. Her flashlight shook in her hand, the light dancing over the frozen figures. There were at least six that she could see clearly. Adult men, naked, hanging by their ankles like animal carcasses. The flesh was bluish from the extreme cold, covered by a thin layer of crystallized ice, faces frozen in final expressions of terror or pain.

“God in heaven!” Margaret whispered.

Behind her, Robert Sullivan remained in the doorway, motionless. He didn’t try to run, didn’t try to attack her; he simply stood there looking at the floor, like a man who finally accepts that his secret has been exposed.

Margaret forced her legs to work, taking two steps back, away from the chamber of horrors. With trembling hands, she grabbed the walkie-talkie clipped to her belt.

“Emergency. I need police immediately at Sullivan Slaughterhouse. Rural Route 47. Multiple… Multiple bodies found.” Her voice cracked. “Send everything you have. Now.”

She kept the flashlight pointed at Sullivan while retreating toward the stairs. He didn’t move, just looked at her with empty eyes.

“How many?” Margaret asked, her voice steadier now, initial shock transforming into controlled fury. “How many men did you kill?”

Sullivan didn’t answer initially, then in a low voice: “I didn’t kill anyone.”

“There are six corpses hanging in your cold chamber.”

“I didn’t kill them,” Sullivan repeated. And there was something in his tone. Not regret, not guilt, but a strange insistence. “They were already dead when they arrived here.”

“What the hell does that mean?”

Before Sullivan could answer, they heard sirens in the distance. Margaret kept her distance from him, hand on the pepper spray she carried, until police cruisers began to arrive.

Sheriff Daniel Cooper was the first to go down to the basement. He was older, grayer than in 1987, but his eyes were still sharp. When Margaret described what she had found, he paled.

“Show me.”

Margaret led him to the cold chamber door. Cooper looked inside and immediately turned away, vomiting against the basement wall. Even having been sheriff for 23 years, even having seen horrific car accidents and bloody crime scenes, this was different.

“Lord in heaven,” he said, wiping his mouth. “Someone call the FBI and the State Police and whoever else we need. This is… this is beyond us.”

In the next few hours, the small rural slaughterhouse was transformed into a federal crime scene. FBI agents arrived from Louisville, forensic teams from Frankfort, crime scene units, television vans began to gather on the road. Robert Sullivan was placed in handcuffs and taken for interrogation. He didn’t resist, didn’t ask for a lawyer immediately, simply sat in the back of the cruiser with a blank expression.

The forensic team began the meticulous process of documenting and removing the bodies. Each was photographed extensively still on site. Measurements were taken. Chamber temperature recorded: 18 degrees—cold enough for perfect preservation.

Dr. Allan Reeves, Kentucky’s chief medical examiner, personally supervised. He was 56 years old and had seen countless deaths, but even he was visibly shaken.

“Preservation is exceptional,” he told Cooper. “Rapid freezing and consistent temperature. These bodies could be years old, but they look fresh. Can you estimate how long they’ve been here?”

“Not yet, but given the technology of the refrigeration equipment, the ice layer… I’d say years. Several years.”

Seven bodies were found in total. All adult men, varying in age from what appeared to be 30 to 60 years old. All naked, all hanging in the same methodical way. And on a table at the back of the chamber, they found something even more disturbing: a veterinarian’s toolbox. Inside were syringes, medications, surgical instruments, and an ID card.

“Dr. Thomas Brennon. DVM,” Federal Agent Jason Hart read aloud. “Address in Louisville. License issued in 1979.”

Cooper felt his stomach drop.

“I know that name. Thomas Brennon. Veterinarian who disappeared three years ago.”

Hart looked at him.

“Disappeared in March 1987. Went out to answer an emergency call and was never seen again. We searched for months. This slaughterhouse was one of the places we investigated at the time.”

“And you found nothing?”

Cooper looked at the cold chamber, at the concrete walls that had hidden this horror.

“We didn’t look in the right place.”

Identification of the bodies began. Fingerprints were collected from frozen fingers. Dental records would be compared. DNA would be extracted. But the first body identified was the easiest. One of the men had a distinct tattoo on his shoulder, a horse in motion. And when they compared his fingerprints with licensed veterinarian records, there was a match.

Dr. Thomas Brennon, 34 years old when he disappeared, left a wife and two young children, presumed dead for 3 years.

Sarah Brennon was notified that night. Cooper went personally. She opened the door with a cautious expression. Calls from the police were never good news.

“Mrs. Brennon, we found your husband.”

She put her hand to her mouth, tears already forming. “Is he… is he alive?”

Cooper shook his head slowly. “No, ma’am. I’m so sorry. But we know what happened to him now, and we are going to get justice.”

Sarah collapsed. Cooper supported her while she sobbed.

“I knew it,” she cried. “I always knew he wouldn’t leave us. I always knew someone took him from us.”

In the following days, the other bodies were identified. They all had one thing in common. They were all horse veterinarians. They had all disappeared in the last 5 years from different parts of Kentucky. Dr. William Morrison, 42, missing in 1985. Dr. James Chen, 38, missing in 1986. Dr. Rebecca Foster, 31, missing in 1988. And so on.

Seven veterinarians, seven families who had lost loved ones without explanation, seven missing persons cases that now had an answer. But why? Why would someone kill veterinarians? And what did Robert Sullivan have to do with it? The answers would come from the interrogation, and the story Sullivan would tell would be darker and more complex than anyone imagined.

Interrogation Room. Jefferson County Police Station. June 16, 1990. 2:00 AM.

Robert Sullivan sat at the metal table, hands cuffed in front of him. He hadn’t slept since the arrest but seemed strangely calm, like a man relieved to finally stop carrying a burden. FBI Agent Jason Hart sat across from him, recorder between them. Sheriff Cooper leaned against the wall, observing. Both were exhausted, but there was no way to sleep until they understood what they had discovered.

“Mr. Sullivan,” Hart began. “Do you understand your rights? You have the right to a lawyer.”

“I don’t need a lawyer,” Sullivan said. “I’m going to tell everything.”

Hart and Cooper exchanged glances. Criminals usually didn’t cooperate so easily.

“Are you waiving your right to a lawyer?”

“I am. I want this to be over.”

Hart turned on the recorder. “For the record, Robert James Sullivan is voluntarily waiving his right to a lawyer and agrees to speak with us. It is June 16, 1990, 2:33 AM. Mr. Sullivan, tell us about the bodies in your slaughterhouse.”

Sullivan took a deep breath.

“I didn’t kill any of them. I need you to understand that first. I’m not a murderer.”

“Then what are you?”

“I’m a gravedigger. A gravedigger who was paid to make bodies disappear.”

Silence filled the room.

“Explain,” Hart said.

“I started this business 15 years ago,” Sullivan began. “Honest slaughterhouse, processing cattle. Small numbers, small profit, but it was a decent life. Then, in 1984, a man came to see me. His name was Victor Koslov.”

“Nationality?” Hart asked.

“Russian or Ukrainian, heavy accent. He worked for important people, rich, powerful. Said they needed someone discreet who could make things disappear.”

“What kind of things?”

“Initially, documents. Financial records that needed to be destroyed without a trace. I had an industrial incinerator here, perfect for the job. They paid well, very well.”

Sullivan looked at his handcuffed hands.

“After a few years, Koslov came back. Said he had a different problem. There was a person who knew things they shouldn’t know, a person who needed to disappear.”

“Dr. William Morrison,” Cooper said. “1985, first veterinarian.”

Sullivan nodded. “I don’t know what he found out. They never told me. Koslov just said Morrison was a problem and needed to vanish completely—no body, no murder case.”

“So you agreed to hide a corpse?”

“They offered me 50,000,” Sullivan said simply. “I was drowning in debt. The bank was going to take the slaughterhouse. 50,000 was… was salvation.”

Hart leaned forward. “How did it work?”

“Koslov brought the body here at night, always in the early morning, always alone. Bodies were always already dead. I swear that. I never killed anyone. I just stored them in the underground cold chamber. Yes, I installed that specifically for this. Built the compartment myself, without hiring anyone. It doesn’t appear on any official building plan. It’s an industrial chamber; can maintain a temperature of 18 degrees indefinitely.”

“Why not simply destroy the bodies? You have an incinerator.”

Sullivan hesitated.

“Koslov said they needed to be preserved. As insurance. In case someone didn’t cooperate, they had evidence stored. DNA preserved perfectly in the cold. Could be used against powerful people if necessary.”

“Blackmail,” Hart said.

“I think so. They never told me details. Just paid me to keep the bodies frozen and my mouth shut.”

“Seven bodies over 5 years,” Cooper said. “All veterinarians. Why? What did the veterinarians know?”

“I don’t know. I never asked. The less I knew, the better.”

Hart drummed his fingers on the table. “You mentioned powerful people. Who exactly?”

Sullivan looked at him with a tired expression.

“Agent Hart, we are talking about the horse racing industry. We are talking about billions of dollars, betting, breeding, sales. When there’s that much money involved, there’s corruption. There always is.”

“Doping,” Cooper said suddenly. “The veterinarians discovered the doping scheme.”

Sullivan didn’t answer, but his silence was answer enough.

Hart leaned back, processing this. Horse racing doping was a federal crime. Giving illegal substances to horses to improve performance or hide injuries could influence race results. With millions bet on each race, people killed for much less.

“Names,” Hart said. “I need names of who was involved.”

“Victor Koslov is the only name I know. He was the intermediary. I never met the bosses.”

“Is Koslov still around?”

“I don’t know. Last time I saw him was March of this year. Brought the last one. Brought Dr. Foster. Said the operation was closing down, that there would be no more bodies. Paid me a final bonus and disappeared.”

Hart made a note. “We’re going to need a full description of him. Everything you remember.”

“I can do better. I have a photo.”

Both Hart and Cooper looked surprised.

“You have a photo of Koslov?”

“Precaution,” Sullivan said. “If something went wrong, I wanted evidence that I was working for someone. I took a photo of him one night when he was unloading the body. He doesn’t know I have it.”

“Where is it?”

“Safe in my office. Combination is 15-28-43.”

Hart left to retrieve the photo. Cooper remained with Sullivan.

“You understand,” Cooper said calmly, “that even if you didn’t kill these people, you are an accomplice. Seven counts of concealing a corpse, obstruction of justice, conspiracy. You’re going to spend the rest of your life in prison.”

Sullivan nodded. “I know, and I deserve it. There is no excuse for what I did. Those families suffered for years without knowing what happened to their loved ones because of me.”

“Why confess now? Why not invent a story?”

“Because I’m tired,” Sullivan said simply. “Tired of living with this. Every night when I closed my eyes, I saw those faces, those frozen bodies. Seven people who had families, lives, dreams—and I turned them into carcasses of meat.”

He looked at Cooper with wet eyes.

“Do you have any idea what it is to wake up every day knowing there are corpses in your basement? That every time you process a piece of meat, you are meters away from where human bodies are stored? It is a living hell.”

Hart returned with a Polaroid photo. It showed a tall man of approximately 50 years, dark hair slicked back, angular face, wearing a black overcoat. He was standing next to a white van.

“This is Victor Koslov,” Sullivan confirmed.

Hart studied the photo intensely. “I’m sending this to our analysts. If Koslov has a record, we’ll find him.”

The interrogation continued until dawn. Sullivan gave every detail he remembered: dates, times, descriptions of how the bodies were delivered. He revealed where he kept the cash payments, buried in metal cans on his property. He described the van Koslov drove: a white Ford Econoline with no markings.

When they finished, Hart turned off the recorder.

“Mr. Sullivan, you will be formally charged later today. The prosecutor will likely offer deals if you cooperate fully.”

“I will cooperate,” Sullivan said. “But there is one thing I need you to understand. The men who killed these veterinarians are powerful people, connected people. They won’t simply let themselves be exposed. They will fight. And people who fight against them tend to disappear.”

Hart smiled coldly.

“Mr. Sullivan, now that this is a federal case, they can’t simply make an FBI agent disappear. That would bring much more heat than any doping scandal.”

But Cooper, who had known Kentucky and its powerful families for decades, didn’t seem so confident.

In the following weeks, the story exploded nationally. “House of Horrors in Kentucky.” “Seven Veterinarians Found in Cold Storage.” The headlines screamed. Television programs covered it obsessively. Comparisons to famous serial killers were inevitable.

But as details emerged about a possible connection to the racing industry, the narrative shifted. This wasn’t about a sick lone killer. It was about organized crime, systemic corruption, contract killings.

Churchill Downs issued a statement denying any involvement. Horse breeders’ associations did the same. Lawyers for rich and powerful people threatened to sue anyone who implicated their clients without proof. But the FBI kept digging.

Victor Koslov’s photo was circulated nationally, and three days later they got a result.

“We have a match,” Agent Hart said, pointing to the computer screen. “Victor Koslov isn’t his real name. It’s Vitaly Kovalsky, American citizen born in Ukraine, immigrated in 1978. Extensive criminal record.”

Cooper, who had been invited to join the investigation as a consultant, studied the screen.

“What kind of crimes?”

“Association with organized crime, extortion, threats. Served 3 years in federal prison in the late 70s. Since then, he’s been smart. No convictions, but constantly under investigation. Last known address is in Lexington.”

“Is he still there?”

“Let’s find out.”

An FBI tactical team executed a search warrant at Kovalsky’s residence at 6:00 AM. The house was modest, far from what one would expect from someone earning money making people disappear. But it was empty, no sign of recent occupation. Neighbors said Kovalsky had left in March, right after making his last delivery to Sullivan. He took two suitcases and drove away in his white van. No one had seen him since.

“He knew this was coming,” Hart said, inspecting the empty house. “Closed the operation and disappeared before we found out.”

But Kovalsky had left something behind. In the attic, behind loose insulation, agents found a cardboard box containing documents—meticulous records of payments, dates, coded names.

“He kept records,” Hart said with disbelief. “Smart criminal always destroys evidence. Why would he keep this?”

“Insurance,” Cooper suggested. “Like Sullivan said. In case he needed protection against his employers.”

The documents were taken for forensic analysis. Codes needed to be deciphered, names identified. It was weeks of work, possibly months. But one thing was clear in the records: payments came from a corporate account, a company called Bluegrass Holdings LLC, registered in Delaware but operating in Kentucky.

Investigation of the company revealed a complex ownership structure: subsidiaries of subsidiaries, shell companies, offshore accounts. Someone had built a financial maze specifically to hide real identities. But the FBI had resources and patience. It took three weeks of painstaking work, tracking bank transactions, corporate records, investment documents. Finally, they discovered three names at the top of the ownership chain.

Richard Pemberton, 58 years old, owner of one of Kentucky’s largest racing stables. His horses had won the Kentucky Derby three times in the last two decades.

Marcos Donovan, 52 years old, chief veterinarian for several major racetracks. He had access to all horses, all medications, all supervision.

Judge Harrison Blackwell, 64 years old, retired Circuit Court judge. He had connections to practically everyone in positions of power in the state.

“My God,” Cooper whispered when the names were revealed. “Pemberton is untouchable. He funds half the politicians in the state. Blackwell… he sentenced cases I judged. And Marcos Donovan… he was friends with Thomas Brennon.”

Hart studied the files.

“Friend or not, he is implicated. These three control Bluegrass Holdings, and Bluegrass Holdings paid Kovalsky. And Kovalsky delivered bodies to Sullivan.”

“How did they choose the victims?” Cooper asked. “Why these specific veterinarians?”

The answer was in Kovalsky’s documents. He had kept brief but revealing notes.

“Dr. William Morrison: discovered doping program after unauthorized autopsy of horse that died in race. Threatened to report to racing commission.”

“Dr. James Chen: tested champion horse’s blood before race, found steroids, confronted Donovan directly.”

“Dr. Thomas Brennon: refused to participate in scheme when approached. Said he would report everything. Considered immediate risk.”

And so on. Each veterinarian had discovered the doping scheme or refused to participate. Each one had been eliminated before they could expose the operation.

“They were doping horses systematically,” Hart said. “Using steroids, stimulants, painkillers. Making mediocre horses win races, betting millions on results they already knew. And any veterinarian who found out or refused to participate was murdered and frozen. Clear message for anyone who thought about talking.”

Cooper felt rage growing. “Thomas Brennon was a good man, a man of integrity, and they killed him for it.”

“Yes, and now we are going to prove it.”

Arrest warrants were issued for Richard Pemberton, Marcos Donovan, and Judge Blackwell. But Hart knew arresting wasn’t enough. They needed solid evidence for conviction. They needed a witness who could connect the suspects directly to the murders. They needed Vitaly Kovalsky.

A national search was launched. Kovalsky’s photo was sent to every law enforcement agency. Borders were alerted, airports monitored. But Kovalsky was a professional; he had disappeared completely.

Until July 15, 1990, a detective in Miami called the FBI.

“We have a match on your Kovalsky. Body found in a canal near the Everglades. Fingerprints confirm identity.”

Hart flew to Miami immediately. Kovalsky’s body was three weeks old when found, partially decomposed by the warm Florida water, but the cause of death was clear. Two shots to the back of the head. Professional style execution.

“They cleaned him up,” Hart told Cooper over the phone. “Only direct witness is dead. Without Kovalsky… case gets much harder.”

“And Sullivan?”

“Sullivan only dealt with Kovalsky. Never met the bosses. Can’t testify against them directly.”

Cooper closed his eyes.

“So they’re going to get away?”

“No, not without a fight. We still have financial records. We still have Kovalsky’s documents. We can build a circumstantial case.”

But both knew the truth. A circumstantial case against rich people with expensive lawyers rarely resulted in conviction, especially in Kentucky where the horse racing industry had immense power.

The arrests were made on July 20. Richard Pemberton was taken from his $3 million mansion in handcuffs. Marcos Donovan was arrested at Churchill Downs in front of dozens of shocked witnesses. Judge Blackwell surrendered voluntarily with a team of five lawyers.

All denied everything. Said Bluegrass Holdings was a legitimate investment, that they didn’t know Kovalsky, that they had no idea the company was being used for criminal purposes.

“We are victims here,” Pemberton’s lawyer declared on television. “My client is a respected businessman, being defamed by an ambitious prosecutor seeking headlines.”

Public opinion was divided. Some saw clearly: powerful people had ordered the killing of seven honest veterinarians. Others questioned: “Where was the direct proof?” Everything was circumstantial.

The trial was scheduled for March 1991. It would be one of the most followed cases in Kentucky history. And then, in January 1991, something changed everything.

Agent Hart was in his office when the phone rang. It was Marcos Donovan, or rather, Marcos Donovan’s lawyer.

“My client wishes to make a deal,” the lawyer said bluntly. “He will testify against Pemberton and Blackwell in exchange for a reduced sentence.”

Hart leaned forward, heart racing.

“What kind of testimony?”

“Everything. How the scheme worked. Who gave orders. Who did what. He kept personal records that corroborate Kovalsky’s documents.”

“Why now?”

There was a pause.

“Between us… Marcos has cancer. Terminal. Six months to a year to live. Doesn’t want to die in prison. And I think… I think his conscience finally caught up with him.”

The deal was negotiated quickly. Marcos Donovan would plead guilty to conspiracy and obstruction of justice. In exchange for full testimony, he would receive a 15-year sentence with possibility of parole after five, knowing he likely wouldn’t live that long.

His first interview with prosecutors was devastating.

“It started almost 10 years ago,” Marcos explained, voice weak. “Richard Pemberton approached me in 1981. Said there was too much money being left on the table, that we could earn millions if we ‘managed’ the horses’ performance properly.”

“Doping,” the prosecutor said.

“Yes. In the beginning, it was small. Anabolic steroids to build muscle, stimulants to increase speed, painkillers to hide injuries. Only a few horses, specific races. And it worked perfectly. Horses that should have come in fourth or fifth won. We made heavy bets because we knew the results. In 5 years, we had made about 40 million dollars.”

“Other veterinarians didn’t notice?”

“Some noticed. Most didn’t care. The entire industry has doping problems; everyone knows. But some… some had a conscience. Threatened to report, like Dr. Morrison.”

Marcos closed his eyes.

“Bill Morrison was a good vet, better person. He did an autopsy on a horse that died after a race in 1985. Found toxic levels of Phenylbutazone and Furosemide. Came to confront me.”

“What did you do?”

“I offered money. A lot of money. He refused. Said he couldn’t be bought, that he was going to the racing commission that week.”

Marcos opened his eyes, tears rolling down.

“I told Pemberton. Pemberton called Blackwell. Blackwell knew Kovalsky through criminal connections he had. A week later, Bill Morrison was missing.”

“And you didn’t do anything?”

“I was terrified. Realized I was involved with murderers, but I was also implicated. If I spoke, I’d go to prison too. So I kept quiet. And when the next vet found out… and the next… and the next… I kept quiet.”

“Thomas Brennon,” Hart said. “Tell us about him.”

Marcos sobbed.

“Tom was my friend. We’d known each other for 15 years. When Pemberton said we needed another vet in the operation, I suggested Tom. I thought… I thought he would understand. That the money would tempt him as it tempted me. But he refused. More than that, he cursed me out. Said I was a disgrace to the profession, that vets had a duty to protect animals, not drug them for gain. Said he was going to the police immediately.”

“So you killed him?”

“No,” Marcos insisted. “I didn’t kill anyone. But I told Pemberton. And Pemberton… he is cold, emotionless. Just said: ‘I’ll take care of it.’”

“How did they get him?”

“Kovalsky called Tom, pretending to be a slaughterhouse owner with sick horses. Tom was the type of person who always helped, even when it wasn’t convenient. He went. And Kovalsky was waiting.”

“How were they killed?”

Marcos shivered.

“Kovalsky used lethal injection. Pentobarbital in a massive dose, the same we use for animal euthanasia. Death was quick. Then he took the body to Sullivan.”

“Pemberton ordered all the murders?”

“Yes. Blackwell was also involved. He provided legal cover, used connections to ensure investigations didn’t go anywhere. When you investigated Tom’s disappearance in 1987, Blackwell ensured no one looked too deeply.”

Marcos’s confession was corroborated by personal records he had kept: coded diaries, financial documents, even recordings of some conversations he had made secretly as insurance.

With this testimony, the case changed completely. It wasn’t circumstantial anymore; it was direct testimony from a participant in the conspiracy. Pemberton and Blackwell realized they were finished. Blackwell tried for a deal too, but prosecutors refused. They wanted to make an example of him. A corrupt judge who used power to protect murderers.

The trial began in March 1991 and lasted six weeks. Marcos Donovan testified for three days, detailing every aspect of the conspiracy. He was visibly sick, emaciated by cancer, but his voice remained steady.

Sarah Brennon was in court every day, sitting in the front row. When Marcos testified about how her husband was murdered, she cried silently. But she also held his hand and said “Thank you” when he finished. Thanked him for finally knowing the truth.

The jury deliberated for two days. Verdict: Guilty on all counts. Conspiracy to commit murder (seven counts). Corruption. Money laundering. Obstruction of justice.

Richard Pemberton was sentenced to seven consecutive life sentences without possibility of parole. Judge Harrison Blackwell received the same. At 65 years old, he would die in prison.

Robert Sullivan, who cooperated completely and whose testimony supported Marcos, received a 25-year sentence. With good behavior, he could get out at 65 years of age.

Marcos Donovan served only 4 months of his sentence. He died in the prison infirmary in July 1991, cancer having spread to his entire body. Before dying, he wrote letters to the families of all the killed veterinarians asking for forgiveness.

“I don’t expect you to forgive me,” one of the letters said. “I don’t deserve forgiveness. But I need you to know. Your loved ones were people of principle. They died because they refused to compromise their integrity. They died as heroes, even if the world never knows.”

Sarah Brennon kept that letter. Years later, when her children were old enough to understand, she showed it to them.

“Your father,” she said, “was murdered because he was a good man. Because he couldn’t be corrupted. And that… that is a legacy you should be proud of.”

Epilogue 2024.

Churchill Downs still holds the Kentucky Derby every year. The horse racing industry survived the scandal, although with much stricter regulations on doping and veterinary supervision.

A memorial was erected in Louisville for the seven killed veterinarians. It lists their names, their dates of death, and an inscription:

“Integrity has no price. These seven people died refusing to compromise. May we never forget their sacrifice.”

Sarah Brennon, now 70 years old, still visits the memorial every year on the anniversary of Thomas’s death. Her children, now adults, come with her. One became a veterinarian, honoring his father’s memory. The other became a federal prosecutor dedicated to pursuing corruption.

The Sullivan Slaughterhouse was demolished in 1992. The land remains empty to this day. No developer wants to build on a site where seven people were stored like meat.

Margaret Chen, the inspector who discovered the bodies, received a commendation from the USDA and a promotion. She never stepped foot in a slaughterhouse again; she transferred to desk work, supervising other inspectors. The nightmares eventually stopped, but she never forgotten what she saw in that cold chamber.

Sheriff Daniel Cooper retired in 1995. In a final interview before leaving office, he said:

“In 35 years of law enforcement, the Brennon case was the hardest. Not just because it was horrific, but because it showed that sometimes the monsters aren’t outsiders. They are respected people in our own community. And that… that is more frightening than any serial killer.”

Vitaly Kovalsky never had a funeral. His body was cremated and ashes discarded without ceremony. No one claimed the body, no one mourned his death.

Richard Pemberton and Harrison Blackwell are still in maximum-security federal prison. Pemberton is 92 years old in a wheelchair, suffering dementia. Blackwell died in 2019 at 93, having served 28 years of his sentence. Neither asked for forgiveness, neither expressed regret.

But sometimes justice isn’t about redemption. Sometimes it is simply about the truth finally coming to light. And seven families finally knowing what happened to those they loved. And seven names on a stone memorial, reminding everyone that principles matter, that integrity matters, that some things are more important than money or power—even when the cost is everything.

News

Nazi Princesses – The Fates of Top Nazis’ Wives & Mistresses

Nazi Princesses – The Fates of Top Nazis’ Wives & Mistresses They were the women who had had it all,…

King Xerxes: What He Did to His Own Daughters Was Worse Than Death.

King Xerxes: What He Did to His Own Daughters Was Worse Than Death. The air is dense, a suffocating mixture…

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil In 1912, a formal studio…

The Cruelest Punishment Ever Given to a Roman

The Cruelest Punishment Ever Given to a Roman Have you ever wondered what the cruelest punishment in ancient Rome was?…

In 1969, a Bus Disappeared on the Way to the Camp — 12 Years Later, the Remains Were Found.

In 1969, a Bus Disappeared on the Way to the Camp — 12 Years Later, the Remains Were Found. Antônio…

Family Disappeared During Dinner in 1971 — 52 Years Later, An Old Camera Exposes the Chilling Truth…

Family Disappeared During Dinner in 1971 — 52 Years Later, An Old Camera Exposes the Chilling Truth… In 1971, an…

End of content

No more pages to load