They Banned His “Boot Knife Tripline” — Until It Silenced 6 Guards in 90 Seconds

At 3:47 a.m. December 14th, 1944, the Arden holds its ground under a fixed band of fog, thick enough to flatten sound and shorten distance. Frost clings to every steel surface. Canvas walls droop under the weight of ice. Inside an improvised workshop marked only by a dim kerosene lamp, Sergeant Thomas Callaway works without pause.

The lamp sputters once, throwing a brief tremor of light across his hands. He does not react. The crate beneath him caks as he shifts to study the small device balanced on his knee. Piano wire coils in a disciplined spiral, guided by hands that once aligned the teeth of brass gears in a Philadelphia repair shop.

The tent is cold enough that tools hold their breath before warming under his grip. Outside, a patrol passes at steady intervals. Boots strike frozen mud with the rhythm of a metronome. No voices, only breath and cloth, and the quiet scrape of a rifle sling adjusting under a parka. The line moves on. The fog closes behind them. Callaway keeps working.

The device in his hands is unofficial. Banned 3 weeks earlier by divisional order. The report had used clear language: “mechanically unsound, tactically reckless.”

“Too many moving parts,” they said. “Too much imagination in a war that demanded predictable equipment.”

But Callaway had seen the pattern of the ambush sites, empty posts, rifles left leaning against trees, no blast signatures, no tracks, only the quiet subtraction of men during the hours between 1:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m. He aligns the spring housing by touch. No haste, no hesitation. The mechanism was never meant for spectacle. It was a simple trigger built from scavenged fragments. A narrow blade guided by controlled tension meant to activate only under a precise shift of weight. No explosives. No report. A silent answer to a silent threat.

The lamp hums faintly as fuel settles. A wrench slips in his pocket as he leans forward to secure the final plate. He pauses long enough to wipe frost from the metal with the sleeve of his jacket. The gesture is quiet, automatic, almost clerical. In the stillness, small sounds become measurements, cloth against steel, the soft pivot of his knee on the crate, the faint expansion of the lamp’s glass.

By 3:55 a.m., the first completed device rests beside him. The shape is unremarkable. Just a narrow assembly meant to fit along a boot sole. He turns it once in the lamp glow to confirm nothing rattles. Nothing binds. Nothing announces itself. A distant truck engine fires somewhere along the timber line. Slow revolutions. Thick winter fuel. A convoy warming for the morning push.

That dull vibration seeps through the ground, reminding him of the system that keeps moving, whether men sleep, vanish, or improvise. In this war, machinery sets the pace. Soldiers adapt or fall behind it. Callaway reaches for the second set of parts. He works faster now, not from urgency, but from certainty. The infiltration teams will test the perimeter again before dawn.

He has seen their timing. He has seen how they move. His unauthorized answer sits heavy on the canvas beside him, its weight small but absolute. By 4:10 a.m., he begins wrapping wire for the third device. The fog outside has thickened. Cloth rustles as the tent wall shifts under a light breeze, then returns to stillness. Every detail feels suspended in the same cold interval.

The question remains unchanged, anchored between the lamp’s glow and the frozen dark beyond the canvas. When command declares an idea forbidden, yet the field demands an answer. The decision falls to the man holding the tools. Callaway never speaks it aloud, but it waits in the quiet. Thomas Callaway’s story begins far from any front line. Philadelphia, early 1920s.

A narrow workshop on a second floor corner above a hardware store. Dust on the window sills. Street cars groaning through morning steam. Inside, a boy learns the discipline of gears from a father who can no longer see them. By 52, the elder Callaway had lost his sight. He taught by sound. He guided his son’s fingertips over worn brass plates, counting teeth by touch, mapping tension through the faint flexcks of metal. In that room, silence carried meaning.

A clock’s slow, irregular tick identified a bent pivot. A fast double tap revealed a loose escapement. Thomas learned to solve problems without looking at them. By 16, he could place his ear against a watch case and name the fault before he opened it. Customers assumed the skill was intuition. It was repetition. The same sequence every time.

Identify the pattern, predict the failure, correct it with the smallest possible movement. That method never left him. He enlisted in 1942 at 34, older than most in his barracks by nearly a decade. The army tested his hands first, then sent him to ordinance repair. Broken rifles, jammed breaches, cracked receiver plates.

He worked in motor pools and field depots where machinery outnumbered people. Trucks idled outside during inspections. Generators coughed in the cold. A warehouse lamp buzzed overhead as he reset trigger assemblies worn thin by constant use. The military saw him as a technician. He saw the war as a giant sequence of mechanical interactions. Every system had a rhythm. Every man’s patrol steps formed a pattern.

Nothing moved without leaving some trace for those who knew how to look. His leather notebook wrote in his breast pocket small diagrams, ratios, angles, notes written during brief quiet spells when a convoy halted for refueling. Most entries were adjustments to existing gear, ways to reduce friction, ways to cut noise, ways to keep a radio mass from vibrating against its bracket during long hauls. Many suggestions were dismissed.

A few were implemented quietly, folded into official equipment without his name. Then the infiltration report started. Centuries gone from their posts without warning. No scuffle, no signal, just absence. Patrol radio men speaking into static at 2:00 a.m. Waiting for replies that never came. The gaps were small but consistent.

Callaway recognized a pattern in the timing the way he once recognized a clock losing seconds. The boot knife trip line came from that observation. Not an upgrade, not a weapon in the traditional sense. A tool built to answer a precise field condition. The narrow moment when an enemy guard steps close enough to notice movement yet not close enough to expect resistance.

A half second where weight shifts heel to toe and balance goes soft. His solution used only tension, a spring, and a blade narrow enough to travel 6 in in a straight line. No noise, no flash, no mechanical complexity beyond what he could assemble by feel. In his mind, it was applied physics, nothing more. Command rejected it immediately.

They cited failure points, weather exposure, the unpredictability of field testing. Their conclusion was final. Callaway built one anyway. He kept it wrapped in oil cloth inside his pack. During night drills, when the range lights were low and officers counted silhouettes from a distance, he tested it on captured German dummies, clean strikes, reliable tension, no misfires.

He logged each result in his notebook, but never submitted the findings. The army valued conformity. He valued function, and in the cold hours before dawn, function tended to prevail. Some solutions never earn recognition. Some never leave a single workshop or a single pack. But they shape the quiet margins where men survive or vanish.

Winter 1944 holds the Arden in a fixed grip. Snow stiffens the forest floor. Roadside ditches freeze into narrow troughs where truck ruts harden overnight. Every route feeding the sector carries weight beyond its cargo, fuel, ammunition, plasma units, spare barrels, all threaded through a lattice so tight that one stalled convoy can stall a regiment.

The system depends on uninterrupted motion, and the forest knows it. Each night, convoys idle in staggered intervals. Engines warm. Exhaust lifts in slow columns that drift into the treeine. The Germans watch these patterns. Their reconnaissance teams move quietly, marking the points where headlights dim or where a driver hesitates at an icy bend.

The Americans know the observation exists, but not where the watchers sit or how many operate in the gaps between trees. What they cannot ignore are the disappearances. Sentry posts along secondary roads begin reporting gaps, not gunfire, not alarms, simply the absence of men who should be standing at their stations. A rifle leaning against a stump. A helmet on frozen grass. No blood in the snow. No cartridges. No drag marks.

The record logs show the same window every time between 2 a.m. and 4:00 a.m. when the fog thickens enough to dull visibility and distort distance. The pattern locks into the daily reports like a slow mechanical fault repeating under strain. Infiltration specialists are at work, likely drawn from SS reconnaissance units trained to move without signatures.

They operate inside the fog using the perimeter itself as cover. They remove isolated guards, observe troop movements, trace the rhythm of American rotations, then retreat before first light. By the time the absence is discovered, the information has already left the forest. Headquarters responds with familiar measures. Patrol frequency doubles.

Rotation intervals shrink until exhaustion becomes another weakness. Command issues standing orders. “Fire at any movement not identified by password.” None of it stops the infiltrators. They wait for guard handoff moments when one man steps down and the next has not yet settled. They track the pauses between the sweep of lanterns. They use stillness as a route.

By late December, the perimeter resembles a machine running with a hidden fault. The lines function, but tension builds in every guard post. Radio operators keep channels open through the night, listening to static for patterns that never come. Trucks leave earlier to beat the fog, arriving coated in ice, their drivers silent from strain. A sense of pressure settles over the sector, thin but constant.

Moments later, the fog thickens again, swallowing sound. A lantern flickers near a supply depot as wind stalls behind the ridgeel line. Across the perimeter, men tighten coat collars and tap rifle stocks against boots to stay alert. The infiltrators move somewhere beyond the first row of pines.

The Americans know it. They just do not know when the next gap will appear. What the sector needs is not another man with a rifle staring into the haze. Human reaction time has limits. In the minutes before dawn, vision narrows, hearing dulls, and even a trained guard drifts into routine. The infiltration teams rely on that routine.

They use the silence as cover, knowing the fog erases small sounds before anyone notices. To counter a silent approach, the answer must be just as silent. A mechanism, not a warning, a trigger that does not depend on awareness. A system that converts the infiltrator’s advantage into his vulnerability. Logistics function on predictability.

Even an enemy steps follow rules when the environment compresses his options. Callaway sees this clearly, the way he once read a watch running slow. Command does not. They apply the same solutions louder and faster, unaware that the problem hides in the quiet space just before a sentry realizes he is no longer alone. In the Arden, the perimeter waits each night for the next absence.

By the second week of December, Callaway begins marking details the way a mechanic tracks a repeating fault. Small indicators, quiet deviations, pieces others acknowledge but never connect. December 9th, morning briefing. Frost still clings to the canvas roofs when the report reaches the table. Another missing sentry checkpoint 7.

No alarm, no struggle, just footprints in the frozen mud. Two sets, both Americansue tread. One set continues past the post, the other stops midstride. The imprint ends sharply, heel half pressed into the frost. No scuff marks, no sideways drag. As if the man rose off the ground and drifted out of the scene. The officers read the log. Initial it. Move on. Callaway keeps the image in his mind.

2 days later, a supply sergeant from the quartermaster line mentions a faint sound near the eastern perimeter. Something like fabric tearing. He heard it around 3:00 a.m. short, almost delicate. He didn’t investigate because it ended before he could pinpoint a direction. In a sector where every tree groans under ice and every branch snaps under weight, a single unfamiliar sound becomes easy to dismiss.

But the sergeant’s tone carries something Callaway recognizes. Uncertainty anchored in a real event. On December 12th, Callaway walks the ground near checkpoint 4, where another sentry vanished two nights before. Snow has drifted over much of the terrain, but the earth beneath tells its own record. Near a half-fallen spruce, he finds a shallow depression about 8 in long, edges soft, centerpressed firm, the shape of a kneeling position, not recent, but not old.

The frost surrounding it has melted slightly and refrozen in a thin skin, suggesting body heat lingered for close to 20 minutes. He studies the sighteline. The depression sits at the precise angle where a sentry would never look during routine sweeps. Too close to the tree line for the flashlights beam. Too far to trigger suspicion.

A patient position, a calculated one. He photographs it with a borrowed camera, winding the film slowly so the gears don’t grind in the cold. Then he steps back, notes the compass bearings, paces the distance from the post, and sketches the arc of a normal guard rotation. The conclusion forms without drama.

The infiltrator waited motionless until the guard turned his back at the usual interval. Before the next rotation, the sentry was gone. When he presents the findings to his lieutenant, the room carries the odor of damp wool and extinguished cigarettes. The lieutenant listens, nods, accepts the print, and sets it beside a stack of broader intelligence reports, German armor clusters, roadblock sightings, supply dumps targeted by artillery. The lieutenant thanks him.

That is the end of it. Headquarters is focused on movements measured in battalions, not a single kneeling mark in the soil, not the absence of one guard, or another, or another. Callaway returns to his workshop without comment. By late afternoon, the fog thickens along the supply road.

A half-loaded truck idles behind the tent, its exhaust pooling in steady pulses. He sits on the same crate he uses for repairs and reviews his notes. Each disappearance aligns with a narrow window. Each kneeling position suggests patience, not improvisation. The infiltrators are not opportunists. They are technicians working according to a method.

In a war driven by timets and fuel allotments, even silent killers follow a schedule. Interrupt the schedule and the method fails. Callaway traces a finger along the edge of his notebook, stopping at the line he wrote earlier that morning. “Change one variable. The ground can be passive or it can respond.” He closes the book, listening to the faint metallic tick of cooling engine parts outside. Sometimes the smallest adjustment turns the whole system. December 13th, 1944.

Evening briefing. The tent walls move slightly under a steady wind from the river. Lanterns cast slow pulses of light along the canvas ceiling. The battalion commander reads from a sheet thick with carbon smudges. His voice stays flat as he restates a policy everyone already knows:

“No unauthorized modifications to defensive equipment. No improvised weapons systems. No deviations from approved sentry protocols.”

He doesn’t name Callaway. He doesn’t need to. The room understands the target of the reminder. Word of the bootmounted knife had traveled along the company streets in less than a day. Mechanics in the motorpool repeated the story with interest. Riflemen joked about ordering their own versions. The officers didn’t joke. They saw a breach in the chain that keeps an army from dissolving into individual initiative. Systems function only when every part stays in line. A short silence settles after the briefing ends.

Then coats rustle, benches shift, and the men file out. Callaway remains seated at the back, hands still, boots planted. He offers no defense and no comment. Argument would not change the order, and he has already completed the calculation that matters. Six sentry posts guard the eastern perimeter, six disappearances over the past cycle.

The spacing between each event forms a pattern, roughly 72 hours. The next window opens tonight or tomorrow before dawn. The approved measures, double rotations, paired patrols, routine call and response have failed every time. The probability of another loss under existing doctrine sits near certainty.

His own device presents an untested alternative, unknown success rate, but measurable, more than zero. Enough to enter the equation. The probability of disciplinary action, if he proceeds, is fixed, a guaranteed penalty. But penalties belong to the future. Dead centuries belong to the present. And Callaway does not assign moral weight to the decision. He treats it as a mechanical problem with human variables.

Two forces in conflict. One force must be altered. A gust of cold air slips beneath the tent flap. The lantern flame bends. Callaway stands, adjusts his collar, and exits without a word. Elsewhere in the camp, diesel engines cool in scattered bursts of ticking metal. Snow collects on crate tops. The supply road grows still.

By the time Callaway reaches his quarters, the sky has dimmed to a flat metallic shade. He kneels beneath his cot and pulls out a canvas bundle. Inside lie the six completed devices. Each one inspected for fit, alignment, and spring consistency. The mechanisms are basic. A blade aligned along the boot sole. A compressed spring held by a release plate.

A narrow pressure trigger tuned to the subtle weight shift of a man leaning forward. A grab, a strike, a lunge, any movement that shifts balance within 12 in of the wearer activates the plate. No blast, no sound beyond metal clearing metal. The blade moves faster than a man can react.

He locks each spring, then tests the tension in small incremental pulls. No misfires, no irregularities. The simplicity gives them reliability. In any industrial system, simple components last longest. Callaway wraps each unit in a strip of canvas, ties the ends, and marks them with chalk so he can recognize them in darkness.

He places them in a torn satchel used for spare wiring. Then he sits on his cot and waits for the sky to finish darkening. Outside, the camp generators cycle down. A short hum, then a low continuous throb. The sound forms the steady pulse of the front machinery holding a line long after men grow tired. By 9 p.m. night has settled.

He lifts the satchel, checks the chalk marks again, and steps into the cold. The system would not change itself. Would you have broken a direct order to adjust one failing variable? December 14th, 1944. 2:15 a.m. The fog sits low across the eastern line, thick enough to blur the outlines of tents and trucks. Diesel exhaust hangs in slow layers trapped beneath the cold air.

Callaway moves through it with a canvas sack over his shoulder. Each step measured, each pause aligned with gaps in the patrol cycle he memorized weeks earlier. He is not hiding. He is navigating the same openings the infiltrators have been exploiting.

Fault lines in the defensive grid created by routine and preserved by habit. The first stop is checkpoint 3. The sentry stands with his rifle tucked under an elbow, shoulders slumped from loss of sleep. He is 19 from Iowa, stationed here for less than a month. Callaway approaches from the expected direction, gives the password, and kneels without ceremony.

30 seconds, just enough time to explain the principle. “Spring-loaded blade triggered by weight shift from an approaching figure, effective against threats from behind or the flank.” The sentry listens. He doesn’t challenge the legality. He doesn’t ask why the officers haven’t issued an equivalent tool. He only nods once, steady but tired.

Callaway secures the device to the outside of the boot, checks the safety position, and moves on. Elsewhere, the fog thickens around the road junction. A supply truck idles unattended, its engine ticking as heat escapes through the hood seams. Callaway keeps close to the darker edges of the path, not for concealment, but to stay outside predictable lines of sight.

Checkpoint five. A corporal with frost on his eyebrows. The same brief explanation, the same acceptance. The installation finishes in under three minutes. Checkpoint 7, then nine. Each sentry responds with quiet understanding. None report him, not because of loyalty and not out of fear. They simply recognize the failure of the official measures.

They know the rhythm of the disappearances. They know tonight fits the pattern. In a system built on timets, the next entry is overdue. By 3:40 a.m., all six devices are in place. The fog is now a wall, 10 ft of visibility at most. The conditions favor anyone willing to move slowly and wait for an opening. Callaway returns to his tent, sets the satchel aside, and sits on his cot with his rifle across his knees.

He keeps the radio tuned to the perimeter frequency, volume low enough to hear the static shift with every faint variation. The generator outside cycles once, its tone dropping, then stabilizing into a deep hum. 40 minutes pass. Nothing, just the steady crackle of empty air. At 4:23 a.m., the silence breaks. A sound cuts through the fog. A fast metallic snap followed by a collapse heavy enough to tremble through the frozen ground.

Not a shout, not a weapon discharge, more like steel completing its travel, followed by weight hitting Earth, then another snap, then a third. Callaway’s hand closes around the rifle, but he does not move. He waits for confirmation. The radio answers first. A burst of static, then a strained whisper from checkpoint 7.

“Contact reported. No shots fired. Three hostiles down, requesting immediate backup.”

Callaway exhales once, slow, controlled. The system has reacted to the variable he introduced. A small alteration placed in the right position can redirect an entire line of events. Outside, the fog continues to drift, indifferent to the body’s cooling in the dark.

Some victories arrive without noise. Some aren’t recognized at all. Dawn comes late on December 14th, 1944. Around 6:20 a.m., the fog begins to lift in slow, uneven layers, revealing the shape of the treeine. The trucks idling with their hoods frosted over the ruts left by night patrols. What it also reveals is the result of the contact reported hours earlier.

The ground near checkpoint 7 shows footprints cutting into the softened crust. Two sets leading in, none leading out. The bodies lie where they fell. Both German, both wearing SS reconnaissance tabs. Their pistols remain holstered, straps still buckled, as if they never reached the point of drawing them.

Combat knives lie a few inches from their hands, metal dulled by moisture. The first man carries a lateral wound high in the thigh, a clean crosscut that severed the artery. The second carries a similar wound, angled lower just inside the abdomen. Blood trails thin toward the frost, pulled in shallow depressions.

Judging by the volume and spread, neither man lived more than 90 seconds after contact. Not enough time to retreat. Not enough time to make a sound. The sentry stands nearby, blanket around his shoulders, hands still shaking from the cold and the suddeness of the event. He explains it in clipped phrases: footsteps moving in the fog close enough to hear fabric brushing against branches; a slight pressure against his boot; a metallic snap; then bodies collapsing behind him. He didn’t turn around, didn’t investigate. He followed instructions, called for support, and waited without moving.

Elsewhere along the line, checkpoint 5 reports its own discovery. One German infiltrator, same profile, same equipment, same kill wound. Snow disturbed by a fall, then frozen again before dawn. The sentry’s footprints remain exactly where they should be, stable, anchored, untouched by struggle. Checkpoint 9 holds the only variation. Two bodies again, but one man still breathes. When the squad arrives, he is unconscious, pulse thin.

They bind the wound, stabilize him, and carry him to the medical tent. He leaves a dark streak of diluted blood behind, marking each point where the stretcher shifts. By midm morning, the assessment is complete. Six infiltrators neutralized in less than 90 seconds. No American casualties, no gunfire discharged, no alarms that could alert the remaining German teams operating further east.

The infiltrators had walked directly into a system they could not anticipate. Silent, reactive, faster than human response. The perimeter, for the first time in days, holds. Military intelligence moves quickly. Interviews begin with the surviving German once he is stable enough to speak.

He confirms the pattern analysts suspected coordinated infiltration by eight-man reconnaissance elements trained to eliminate isolated guards and chart approach routes for a broader action. The teams operated without radio, relying on pre-arranged timing. When three elements failed to return, the operation was called off. Their maps remain unfinished. During the interrogation, the officers present display one of Callaway’s devices.

They place it on the table with the trigger disabled. The German stares at it in silence for 30 seconds, eyes fixed on the spring assembly, the blade, the compact frame. When he finally speaks, his English is uneven but clear enough. He asks, “Who builds this?”

The official answer is simple. “No one.”

No record, no approval, no inventor of note. The logs will show only that a threat was neutralized. Unofficially, every man in the battalion knows the truth. They saw the fog lift. They saw what lay on the ground. Some solutions never enter doctrine. They exist only in the spaces where rules fail. December 15th, 1944. Around 9:00 a.m.

Frost clings to the edges of tent flaps outside battalion headquarters. Diesel from a warming generator drifts low, mixing with the morning breath of men waiting for orders. The convoy lines remain still, engines cold, as if the entire perimeter holds a steady inhale. Callaway steps inside the headquarters tent when summoned, boots leaving thin, damp marks on the planks.

Three officers wait at the table. His company commander sits closest, uniform creased from an overnight shift. Beside him, a divisional intelligence officer reviews a folder with pages marked by grease and pencil. At the far end sits a lieutenant colonel from Ordinance Review, collar rigid, handsfolded with exact alignment.

No military police, no legal clerk. The space carries the quiet weight of a system evaluating its own seams. The intelligence officer begins. His voice stays even. “Six confirmed enemy dead. Zero American losses. A disrupted German reconnaissance effort. Interrogation notes indicating a broader offensive delayed for lack of terrain data.” Each phrase is read the same way fuel logs are read. Line after line, weight after weight. Evidence that the machine of defense still holds.

A shift in the tent fabric brings a brief draft. It cools the table surface. The ordinance officer speaks next. “Unauthorized deployment of unapproved equipment. Violation of directive. Introduction of untested mechanical devices near friendly personnel.”

His tone does not rise. His words fall one by one like items placed on a scale already carrying load. The company commander, still silent, slides two documents forward. The paper edges stop in front of Callaway’s gloves. One is a commenation, typing crisp, date already filled. The other is a reprimand for insubordination.

Both stamped, both ready, both incompatible with each other, yet equally accurate. Callaway does not pick them up. He stands as if listening for a sound outside the tent. Trucks shifting, boots on gravel, anything steadier than the moment. He waits for the real question. The lieutenant colonel provides it.

“Sergeant, why didn’t you seek approval through proper channels before deployment?”

Callaway answers without delay. “Because proper channels failed six times, and I calculated tonight would be the seventh.”

A pause follows. A long one, the kind found in the space between radio transmissions. When the set warms and the signal clears, the intelligence officer notes something in his book. The ordinance officer glances between the commenation and the reprimand, then toward Callaway. The paper remains unsigned.

The system for a moment hesitates between matching procedure and matching outcome. The company commander resolves it. He issues a verbal order. “All six devices will be collected immediately. Ordinance specialists will examine them, test them, decide if they merit redesign and controlled production.”

Callaway’s notes and drafts will be transferred to divisional engineering before nightfall. His actions will not be formally recognized. They will not be formally punished. They will simply be removed from the paperwork. The meeting ends 12 minutes after it began. The tent returns to routine noise.

Typewriter keys, map pins shifting, a pot settling on a stove. Back with the unit that afternoon, Callaway’s lieutenant walks beside him for a few paces. He keeps his voice low. “Higher up decided, ‘You didn’t do anything.’” Then he nods once and moves on, leaving the words behind like a footprint in soft ground.

Callaway understands some parts of the war function in places where forms cannot follow. Some successes must remain unrecorded so the machine can continue forward without contradiction. In a system built on chain of command, silent solutions often carry the greatest weight. Thomas Callaway received no medal for the night of December 14th, 1944.

The forms drafted in headquarters never left the table. By the next morning, the convoy routes were already clearing ice, fuel trucks warming their engines, schedules returning to their usual pressure. His name moved back into the routine ledger of personnel, the place where most stories remain unrecorded. His boot knife tripline device never appeared in an official manual.

It was logged, tested, discussed in limited correspondence, then archived under technical evaluations. But fragments of its engineering circulated through classified ordinance reports in 1945. Brief mentions of spring weight, blade velocity, ground stake angles. By the post-war years, those fragments reemerged in special operations equipment.

Quiet traces of a fieldbuilt idea carried forward by men who recognized its logic. A mechanical answer to a human gap, a shift of wind across an empty road, can say as much as a citation. Callaway survived the war. He returned to Philadelphia, stepping off the train with a single duffel. Within a month, he reoped his father’s clock repair shop, its windows still lined with brass gears and pendulums.

He slid back into civilian rhythm without ceremony. Customers remembered him for steady hands and precise work, not for anything he’d done overseas. When neighbors asked years later about the infiltration incident, he explained it without embellishment.

“Something wasn’t working,” he said. “I adjusted the mechanism. It worked.”

He described the war the same way he described a broken mainspring, parts under strain, a system losing alignment, a task completed because he knew how tension should feel when it settled back into place. By midday, the sound of trucks outside the shop would drown out the clocks for a moment. Then the ticking returned layer by layer. There were thousands like him in World War II. Mechanics, radio repairmen, engineers, draftsmen. They managed the war’s machinery so the larger structure could function. Their work stayed quiet, technical, and distant from the stories told afterward.

They did not lead charges or raise flags over captured cities. They corrected faults others didn’t see using skills learned in basement, garages, and small businesses long before the war pulled them in. Their monuments are absences. The convoy that passed through a forest road without incident.

The sentry who returned from nightw watch unchallenged. The enemy assault that never materialized because reconnaissance teams failed to report back. These spaces, unmarked and unseleelebrated, carry the trace of men whose solutions prevented events rather than cause them. A truck that never leaves the road still influences the line behind it.

Callaway’s legacy rests in what did not occur on December 15th, 1944. A larger German attack intended to exploit mapped American positions found those positions still uncertain. The terrain remained uncharted because six infiltrators failed to return after walking into a fog bank where the usual variables no longer held. In a conflict defined by mass production and coordinated supply, one adjusted mechanism changed the chain of cause and effect.

The industrial logic of his design, spring tension, blade weight, the angle of force belongs to a different register of warfare. Not courage, not sacrifice. Applied physics under pressure delivered by someone who understood that survival can depend on shifting a single component in an equation everyone else assumed fixed. History often records the men who fought conventionally.

It rarely records the ones who thought differently. Would you have remembered?

News

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS In the early autumn…

She Disappeared — 15 Years Later, Son Finds Her Alive in an Attic Locked with Chains.

She Disappeared — 15 Years Later, Son Finds Her Alive in an Attic Locked with Chains. Lucas parked the pickup…

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901)

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901) In the spring…

“You’re Mine Now,” Said The British Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved For Days

“You’re Mine Now,” Said The British Soldier After Seeing German POW Women Starved For Days September 1945, 1430 hours. A…

What Genghis Khan Did to His Slaves Shocked Even His Own Generals

You’re standing in the war tent when the order comes down. The generals fall silent. One of them, a man…

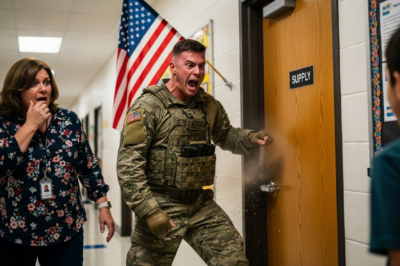

Teacher Locked My 5-Year-Old in a Freezing Shed for Lunch… She Didn’t Know Her Green Beret Dad Was Coming Home Early.

Chapter 1: The Long Way Home The C-130 transport plane touched down on American soil with a screech of tires…

End of content

No more pages to load