September 1st, 1943. The air at Rabal Airfield is thick, a soupy mixture of humidity, volcanic dust, and the faint sweet smell of aviation fuel. Inside an operations tent, Lieutenant Commander Saburo Sakai, a living legend, a samurai of the skies, holds a piece of paper.

One of his eyes is a milky white void, a permanent souvenir from an American dauntless dive bombers’s tail gunner. But his good eye, the one that has guided him to over 60 aerial victories, scans the intelligence report and then a sound cuts through the oppressive heat. It’s a laugh. It’s not a small chuckle. It’s a deep, genuine, dismissive laugh.

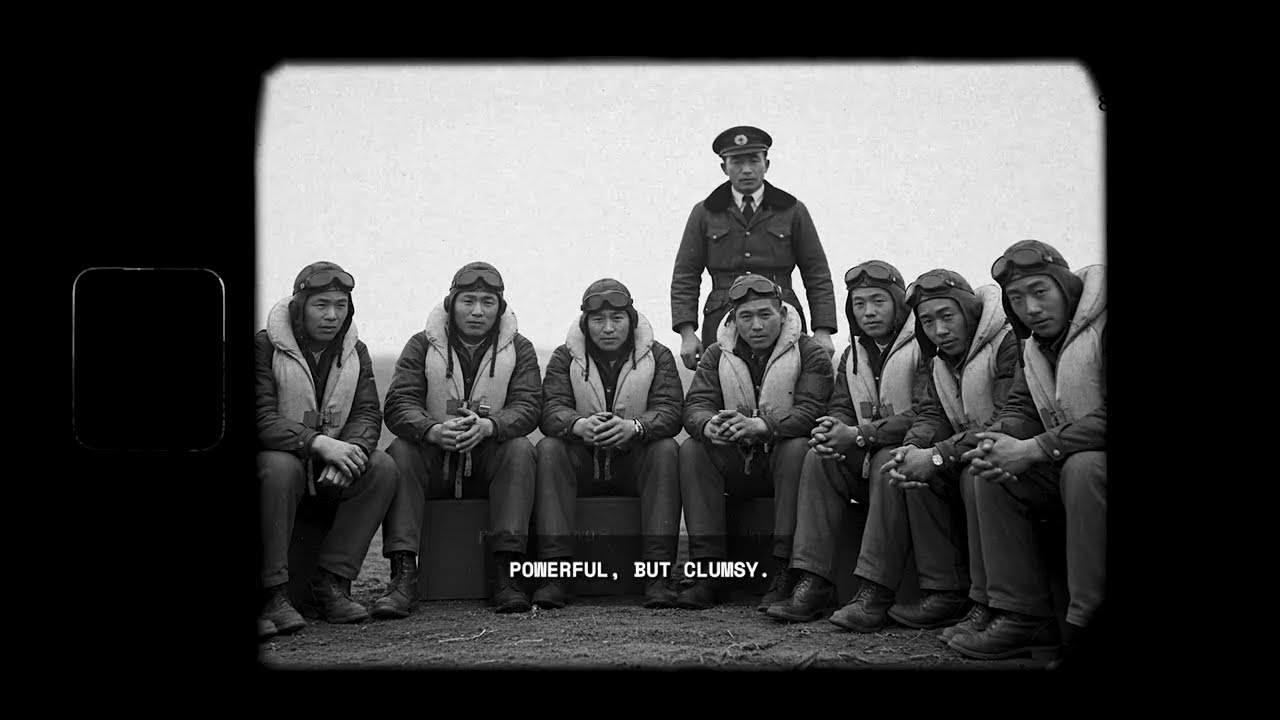

He reads the words aloud to the other pilots, the elite of the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service. The Americans have a new fighter. They call it the Hellcat. The name itself is absurd, a piece of brutish American marketing. But it’s the specifications that are truly comical. Our intelligence suggests it weighs nearly 6 tons, twice our zero.

More laughter fills the tent, twice the weight. To these men, artists who painted death in the sky with aircraft that felt like extensions of their own bodies, this was insanity. They flew the Mitsubishi A6M0, an aircraft so light, so nimble, it could outturn anything the Allies had ever thrown at them.

For 2 years, the Zero had been the undisputed master of the Pacific. It was a scalpel, a rapier, a whisper on the wind, and the Americans were sending a fat, heavy, clumsy sledgehammer to fight it. Through the tent flaps, Sakai could see them lined up on the pierced steel planking runway, his squadron zeros. They were beautiful, sleek, and impossibly deadly.

They had swept the skies of British hurricanes, American P40s, and Dutch Brewster Buffaloos. They were the embodiment of a warrior philosophy that prioritized skill, spirit, and agility over brute force. This new American plane, this Hellcat was an insult. It was a flying truck.

It was a continuation of a failed American design philosophy that tried to solve problems by throwing more metal at them. The consensus in the tent was clear. The Hellcat would be another easy kill, a footnote in the glorious history of the Zero. But what Saburro Sakai and every pilot laughing in that tent could not possibly know was that this joke, this overweight, ugly American machine, was not just a new plane. It was a death sentence.

It was the physical manifestation of an industrial and tactical philosophy so powerful, so ruthless that it would not just defeat the zero, it would systematically annihilate Japanese naval aviation. In less than 2 years, this failure of design would be responsible for over 5,000 Japanese aircraft kills. It would achieve an astonishing kill ratio of 19 to1.

The laughter in that tent was the last echo of an era. The era of the zero was over. The age of the Hellcat was about to begin, and it would be born in fire and fury, rewriting the entire mathematics of air power and turning the Pacific sky from a dueling ground into a slaughterhouse.

To understand the sheer shock that the Hellcat represented, you first have to understand the myth, the legend of the plane it was built to kill, the Mitsubishi A6M0. In late 1941 and early 1942, the Zero was less an aircraft and more a force of nature. It appeared in the skies over Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and Singapore like a ghost, a silver phantom that defied the known laws of aeronautics.

Allied pilots who encountered it and survived spoke in hushed, disbelieving tones. They described a fighter that could climb like a rocket and turn on a dime, dancing circles around their own sluggish planes. The numbers were so one-sided they seemed like propaganda. At Pearl Harbor, the Japanese lost just 29 aircraft while destroying or crippling over 300 American planes.

In the conquest of the Philippines, it was seven losses against 103 destroyed. The story was the same everywhere. The Zero was invincible. When American engineers finally got their hands on a captured Zero in 1942, the Akutan Zero, they were baffled. They ran the performance numbers, and at first they refused to believe them.

A fighter with the range of a light bomber, the agility of a pre-war biplane, and the firepower to shred anything it faced, it seemed impossible. The secret was a design philosophy that was as brilliant as it was brutal. The Zer’s designer, Jiro Horoshi, had been given an impossible task. Create a carrierbased fighter that was faster, more agile, and had a longer range than any land-based fighter in the world. To achieve this, he made a pact with the devil.

He sacrificed everything, and I mean everything, for performance. The Zero was built from a top secret aluminum alloy called extra super duralamin, making its airframe unbelievably strong yet feather light. But that was just the start. There was no armor plate to protect the pilot.

A single bullet in the right place, and the man flying the plane was dead. There were no self-sealing fuel tanks. A stray round could turn the entire aircraft into a ball of fire. The radio was often removed to save a few extra pounds. Every single component was scrutinized, and if it wasn’t absolutely essential for flight or combat, it was discarded.

The result was a masterpiece of minimalist design. Its wing loading, the amount of weight each square foot of the wing has to support, was incredibly low, just 22 lb per square foot. This gave it a phenomenal turning radius of just over 600 ft. It could literally fly circles around its opponents.

Hiroyoshi Nishasawa, Japan’s future ace of aces, wrote in his diary, “Flying the Zero is like wearing wings. The aircraft responds to thought, not just control input. American planes fly like trucks. Powerful but clumsy. They build fighters like they build cars. Heavy, overbuilt, wasteful. This was the core belief of the Japanese naval air service.

They believed in the supremacy of the pilot, the samurai spirit, enhanced by an aircraft that was a pure extension of his will. They saw air combat as an art form, a duel of skill. And in their artists hands, the zero was the perfect brush. So when the first intelligence reports on the Grumman F6F Hellcat trickled in during early 1943, they were met with utter contempt.

The specifications read like a list of everything a fighter plane shouldn’t be. Its loaded weight was over 12,000 lb. The Zero was barely 5800. Its wing loading was a ponderous 36.5 lb per square foot, which suggested a turning radius of nearly 1,000 ft. In the turning dog fights that Japanese pilots mastered, the Hellcat would be a sitting duck. It was a brick. And the list went on.

It carried armor plate everywhere, 212 lb of it, just to protect the pilot. It had bulletproof glass. Its fuel tanks were massive and self-sealing, adding hundreds of pounds of weight. It carried 2,400 rounds of ammunition for its 650 caliber machine guns. It was everything the Zero was not.

Heavy, complex, and built for survival, not just performance. Captain Manoru Jenda, the tactical genius who had planned the Pearl Harbor attack, reviewed the specs and wrote a dismissive analysis that would become infamous. The Americans have learned nothing, he concluded. This Hellcat represents the continuation of their failed philosophy.

Attempting to overcome pilot skill with a weight of machinery. A zero will fly circles around it. The mathematics seem to prove him right. The entire Japanese tactical doctrine was built around the turning fight. Get into a horizontal circle with the enemy. Use the zero superior agility to get on his tail and finish him.

Based on the numbers, the Hellcat was designed to lose that fight every single time. The Japanese pilots laughed because they saw the Hellcat not as a threat, but as confirmation of their own superiority. They were the artists, the samurai. The Americans were just factory workers churning out clumsy machines.

They believed they were fighting a war of spirit and the Hellcat was a soulless beast of iron. They were about to learn in the most brutal way imaginable that they had fundamentally misunderstood the nature of the war they were fighting. The Americans weren’t coming to duel, they were coming to exterminate.

The first hint that something was terribly wrong with this picture came on September 30th, 1943 near Marcus Island. Petty Officer First Class Yoshio Fukui was a veteran zero pilot flying escort for a reconnaissance plane. He knew the sky. He knew its rhythms, its dangers, its predictable patterns.

When he spotted six dark blue shapes climbing from the southeast, his brain processed them through the lens of his experience. His first thought recorded in his afteraction report was that they were B-25 bombers flying a strange route. They were too big, too bulky to be fighters. Then the shapes turned and Fukulele saw the silhouette for the first time.

A single massive radial engine, a thick barrel-chested fuselage, and wings that looked almost comically short and stubby for such a large body. First encounter with F6FT type fighter, he would later write. Initial impression, Americans have mounted fighter guns on a torpedo bomber. It was an ugly, brutish looking thing. Fukulele felt no fear, only a sense of professional curiosity.

He and his wingman would deal with this lumbering beast using the timehonored tactics that had never failed them. He rolled his zero into a diving turn. the standard opening move. The plan was simple. Use the Zero’s exquisite agility to slice inside the clumsy American’s turn, get on his tail, and send him burning into the Pacific. He expected the heavy American fighter to continue straight.

Unable to follow his nimble maneuver, he would curve neatly onto its 6:00 position, a position from which no Allied pilot had ever escaped him. But then the impossible happened. The Hellcat didn’t try to turn with him. It didn’t run. It did. Something that violated every rule of air combat as Fukui understood it. It went vertical. Fukui watched in stunned disbelief.

The Hellcat simply pointed its nose at the sky and climbed, not sluggishly, but with a terrifying, ferocious power he had never witnessed. The source of this power was something the intelligence reports hadn’t properly conveyed. The Pratt and Whitney R2800 double wasp engine. A 2,000 horsepower 18 cylinder marvel of engineering.

It produced over 700 more horsepower than the Zero’s Nakajima Sakai engine. That engine was now pulling the 6-tonon Hellcat upwards at a staggering 3,500 ft per minute. Fukulele, trying to follow, felt his own lightweight zero shutter. His air speed bled away rapidly as his less powerful engine struggled against gravity.

The hunter had suddenly, inexplicably, become the hunted. At 15,000 ft, the Hellcat pilot performed a maneuver that should not have been possible for a plane of its weight. A perfect hammerhead stall turn, a graceful, deadly pyouette in the sky that reversed its direction and placed it directly above Fukulele, dropping onto his tail like a hawk.

The American pilot opened fire. Fuku’s report captured the shock. Six machine guns, not the four we expected. The volume of fire was unprecedented. In 3 seconds, 1750 caliber rounds tore through his Zero’s unarmored fuselage. The noise was deafening, the impacts jarring his entire body.

Only by instinctively throwing his plane into a desperate spin did he manage to escape the stream of tracers. He barely nursed his riddled aircraft back to Marcus Island. His wingman, Petty Officer Secondass Masau, never returned. Neither did the reconnaissance plane they were supposed to be protecting. The first blood had been drawn and it was the Hellcats. Fukui’s report and a tremor of confusion through the Japanese command.

The fat, clumsy American plane wasn’t supposed to be able to do that. It wasn’t supposed to be able to climb. The rules, it seemed, were changing. Just a week later on October 5th, the lesson was driven home with even greater brutality over Wake Island.

Lieutenant Yoshio Sheiga led a flight of 12 zeros to intercept what they assumed was another minor hit-and-run raid by American carriers. They climbed to 20,000 ft, positioning themselves perfectly. Below us, 12 F6F fighters, Shea wrote in his diary. We held every advantage. Altitude, position, surprise. Victory was certain. This would be a textbook engagement. A classic bounce from above.

The Zeros dove. But as they screamed down on the unsuspecting Americans, the Hellcat pilots did something baffling. They didn’t panic. They didn’t scatter. They didn’t even try to turn and engage. They simply held their formation nose down into a gentle dive and accelerated.

The Zeros built for agility, not speed in a dive, struggled to catch the heavier, more streamlined Hellcats. As the Japanese pilots opened fire from maximum range, hoping for lucky hits on the unarmored American planes, they saw their bullets sparking off the fuselages to little effect. They were hitting planes built with that 212lb cocoon of armor around the pilot with self-sealing fuel tanks that could absorb dozens of hits and seal the punctures.

The Zero, a plane that could be brought down by a handful of well-placed rounds, was firing at a flying tank. Then, as the Zeros pulled out of their dives, having wasted precious altitude and ammunition, the Hellcats executed their counterattack. But it wasn’t a dog fight. It was a physics lesson. They didn’t turn.

They used their immense engine power and their weight, the very thing the Japanese had laughed at, as a weapon. They climbed. They used their superior horsepower to regain altitude at a rate the Zeros simply couldn’t match. At high altitudes, the Zeros unsuperched engine gasped for air, its performance dropping off dramatically. At 25,000 ft, the Hellcat was still a beast. Shea watched in horror.

“They came down on us like hawks on sparrows,” he wrote. “Their weight gave them speed we couldn’t match. They would dive, fire those six terrible guns, then climb away before we could react. It was a slaughter. The Hellcats refused to play the Zero’s game. They refused the turning duel. They fought on their own terms using slashing, high-speed passes.

What American pilots called boom and zoom tactics, dive, fire, climb, repeat. It was clinical, efficient, and utterly devastating. Eight zeros were shot down in minutes. Not a single Hellcat was lost. The myth of the Zero’s invincibility was shattered over Wake Island.

The Japanese pilots had brought their swords to the duel, but the Americans had shown up with rifles and were shooting them from a hilltop a mile away. The horrifying truth was dawning across the Pacific. The Hellcat wasn’t designed to outturn the Zero. It was designed to make turning irrelevant.

The Americans had looked at the zero’s strengths and weaknesses and created a machine and a doctrine designed specifically to nullify the former and exploit the latter. This new American doctrine was called energy fighting. It was a philosophy of air combat that treated a fighter not as a duelist rapier but as a reservoir of kinetic and potential energy. Speed was kinetic energy. Altitude was potential energy.

The goal was to always have a higher energy state than your opponent. Lieutenant Commander Jimmy Thatch had developed a tactic called the Thatche, where two friendly fighters would fly in a pattern that constantly covered each other’s tails, luring enemy fighters into the guns of their partner. This combined with the Hellcat’s strengths created a deadly new system.

Japanese pilots trained as individual samurai were now facing a coordinated ruthless machine. Lieutenant Commander Tao Tanameisu, a 32 victory ace, tried to explain this new reality to his pilots at Rabul in November 1943. Forget everything you know about air combat, he told them his voice grim. The Americans have changed the rules.

They no longer fight our fight. They fight like executioners, not warriors. He explained how the Hellcats worked in pairs, a leader and a wingman, one high, one low. While a zero pilot was desperately trying to turn with one, the other was already diving on him from above. Their radios, Tanamezu noted, which we laughed at for adding weight, let them coordinate perfectly. We fly as individual samurai. They fight as a single machine.

This was the crux of it. Japan had perfected the warrior. America had perfected the system. And the system extended far beyond the cockpit. The Americans had a secret weapon the Japanese couldn’t even comprehend. radarg guided fighter direction. While Japanese pilots scanned the vast empty sky with the naked eye, relying on instinct and luck, Hellcat pilots were being guided to their targets by controllers on the carriers below.

These controllers stared at glowing radar screens that could see Japanese formations from 50, 70, even 100 miles away. They were chess masters positioning their Hellcat pieces for a perfect checkmate. Lieutenant Saddamu Kamachi described the terrifying experience. We were climbing through clouds when they hit us. No warning, no visual contact.

Hellcats diving from above, exactly on our heading, perfectly positioned. They knew where we were, our altitude, our course. We were blind men fighting those who could see in the dark. The technological gap was becoming a chasm. The Hellcat’s six Browning M250 caliber machine guns fired a combined 4,500 rounds per minute.

Each bullet was a heavy high velocity slug that carried four times the kinetic energy of the Zero smaller 7.7 mm rounds. A 1second burst from a Hellcat put a devastating amount of lead into the air, enough to shred the Zero’s delicate, unarmored frame. The Zero was a glass cannon. The Hellcat was a flying anvil, and it was dropping on them from a great height.

But perhaps the most decisive factor wasn’t the planes, the tactics, or even the radar. It was the pilots. Japan had started the war with a small elite cadre of the best trained pilots in the world. Their training program was legendarily difficult, taking 3 years and requiring at least 700 flight hours before a pilot saw combat. They were truly the best of the best.

But they were a finite resource, and the Hellcat was killing them faster than they could be replaced. By early 1944, the relentless attrition was catastrophic. The demanding three-year program was a distant memory. New Japanese naval pilots were being rushed to the front with as little as 300 hours of flight time, then 200.

Crippling fuel shortages meant most of that training was done in gliders or outdated aircraft. Gunnery practice was limited to a handful of rounds. They were being sent into combat against the deadliest fighter system ever created with barely enough training to take off and land safely. Meanwhile, the American war machine was operating on a different scale of reality.

The United States had a massive systematic pilot training program. American pilots arrived in the Pacific with a minimum of 300 hours, often more, with at least 50 of those hours in the Hellcat itself. They had fired thousands of practice rounds. They had practiced carrier landings until it was muscle memory.

They had learned energy fighting tactics in the safe skies over Texas and Florida. Not in a life ordeath struggle against veteran aces. Lieutenant Commander Yoshihiro Hashimoto, a training officer in Japan, wrote a heartbreaking final report. We are sending children to fight professionals. Enen Yamamoto arrived at the front yesterday. He had never fired his guns in flight.

We have no ammunition for practice. He had never flown at night. We have no fuel for such training. He lasted 7 minutes in his first combat. The samurai were all dead. Now Japan was sending peasants with swords to face a mechanized army. The culmination of all these factors, the superior aircraft, the revolutionary tactics, the radar, the overwhelming pilot skill gap, led to a single horrifying day in June 1944 that would forever be known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. The Japanese Navy in a desperate gamble committed its

entire remaining carrier force to Operation Ago, a plan for a decisive battle to destroy the American fleet in the Philippine Sea. They gathered nine carriers and 450 aircraft scraped together from every corner of the Empire. This was it, the last stand. Against them sailed the US Navy’s Task Force 58, 15 carriers, over 950 aircraft, including 450 F6F Hellcats.

Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa launched his attack in four waves, still clinging to the belief that the superior range of his aircraft and the Bushidto spirit of his pilots would carry the day. The first wave of 69 aircraft was detected by American radar when they were still 150 mi away. The chess game began. Shipboard fighter directors calmly vetored dozens of Hellcats to the perfect interception point.

They set up the ambush flawlessly with a massive altitude advantage. The sun at their backs approaching from the Japanese plane’s blind spots. Lieutenant Zenji Ab leading the Zero escort saw them just minutes before the attack. His blood ran cold. He described it as a steel curtain, an enormous, terrifying wall of dark blue fighters stacked in layers from 20,000 to 30,000 ft waiting for them.

Every advantage was theirs, he recalled. The engagement was not a fight. It was an execution. It lasted 12 minutes. Of the 69 Japanese aircraft in that first wave, 42 were shot down. The Zeros tried to engage in their familiar turning dog fights. The Hellcat pilots simply refused.

“We’d make a high-side run, shoot one down, and zoom climb back to altitude,” reported Commander David Mccell, the top American Navy ace. “The try to follow, stall out, and another Hellcat would pick them off.” The slaughter continued all day. Wave after wave of Japanese planes flew into the buzzsaw. By the end of the day, Japan had lost 346 carrier aircraft and dozens more land-based planes.

The American losses, just 30 aircraft from all causes. In the ready rooms of the American carriers that night, pilots joked, “Why hell? It was just like an oldtime turkey shoot down home.” The name stuck. The Imperial Japanese Navy’s carrier AirArm, the force that had terrorized the Pacific for 2 and 1/2 years, had effectively ceased to exist in a single afternoon.

The psychological impact on the few surviving Japanese pilots was profound. They developed what military psychologists would later term hellcat psychosis. They were no longer fighting other men. They were fighting an invisible allseeing system that guided an indestructible monster. Admiral Ozawa wrote in his afteraction report, “The enemy’s radarguided fighter direction achieved something we thought impossible.

The industrialization of air combat, our pilots, no matter how skilled, were engaging not planes, but a system.” The laughter from that tent in Rabbal had turned into a scream of collective horror. Unable to compete conventionally, Japan resorted to the ultimate act of desperation. The kamicazi. Vice Admiral Takajiro Onishi, the father of the kamicazi corps, justified it with cold, brutal logic.

If a zero attacks a carrier conventionally, the probability of success is near zero. The Hellcats will destroy it. If the zero becomes a bomb, the probability of hitting increases to 30%. The pilot dies either way. At least as a kamicazi, his death has meaning.

It was the final tragic admission of the Hellcat’s total dominance. The only way to beat the system was to turn their own pilots into guided missiles, hoping to slip through the steel curtain. Even here, the Hellcat proved its worth, transforming from a hunter into a shield. During the battle for Okinawa in 1945, Japan launched nearly 2,000 kamicazi sorties.

Hellcats flew tens of thousands of combat air patrols, forming a protective umbrella over the fleet. They became masters of shooting down the desperate suicide attackers, preventing an estimated 80% of them from ever reaching their targets. It was a grim final chapter with the Hellcat standing as the final guardian against an enemy that had been technologically and tactically bankrupted.

When the war ended, the sheer scale of American industrial might became terrifyingly clear to the defeated Japanese. The Grumman factory in Beth Page, New York, had operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. At its peak, a brand new F6F Hellcat rolled off the assembly line every single hour. Grumman built over 12,000 Hellcats in just 30 months.

In 1944 alone, America produced 35,000 fighter aircraft of all types. Japan in that same year managed to build just over 5,000. Jiro Horoshi, the designer of the Zero, studied a captured Hellcat after the war, and his conclusion was devastatingly simple. “We designed an aircraft for 1941,” he said. “They designed an aircraft system for 1945.

While we were perfecting the sword, they were building the industrial age.” In his final interview before his death in the year 2000, Saburo Sakai, the legendary ace who had laughed at that first intelligence report, was asked about the Hellcat. His words captured the totality of its impact.

“The Zero made Japan a great naval power,” he said. “The Hellcat made Japan realize it was never as great as it believed. We thought we were samurai. The Hellcat showed us we were just men with outdated weapons facing the future. Every Japanese pilot who survived the war survived because a Hellcat pilot chose to let them live.

That is the ultimate defeat, existing at your enemy’s discretion. The Japanese pilots had laughed at the F6F Hellcat. They laughed at its weight, its size, its ugliness. They saw it as a clumsy, brutish machine, an embodiment of everything they despised about their enemy. But they had failed to understand what that extra weight represented. It represented a bigger engine they couldn’t build.

It represented armor plate to protect a pilot they couldn’t replace. It represented self-sealing fuel tanks and heavy radios and a ruggedness that reflected the philosophy of the nation that built it. A nation that could afford to trade metal for men’s lives. A nation that built not just a better fighter, but a better system of war.

By the time the Japanese pilots stopped laughing, their mockery had turned to kamicazi missions. Their proud air force had been erased from the sky, and their empire was in ruins. The Hellcat had the last laugh. It always did.

News

Happiness: The Healer Who Became the Most Feared Killer of the Baiano Hinterland, 1878

Bahia, 1878. On a hot March night, Colonel Joaquim Ferreira da Silva lay dying in his bed. His screams echoed…

She Was Pregnant by Her Grandson — The Most Inbred Matriarch Who Broke All Boundaries

In the mountains of West Virginia, there’s a cemetery where the headstones tell a story that defies nature itself. The…

The Japanese Squadron Disappears in World War II — 60 Years Later, Bunker is Found

The backhoe stopped abruptly when its metal claws hit something that wasn’t dirt or rock. Klaus Bergman, the operator, turned…

How 50,000 Gallons of Free Fuel Doomed Hitler’s Elite Panzer Division

In the dead of a Belgian winter on December the 17th, 1944, the most powerful armored weapon of the Second…

The SEAL Captain Asked, ‘Any Combat Pilots Here?’ — She Quietly Rose to Her Feet

The desert knight was restless. Inside the forward operating base, the air was thick with dust, diesel, and the faint…

Navy SEAL Asked Her Rank As A Joke — Until Captain’s Shadow Hit the Floor Behind Him

“Hey, dish rag.” Petty Officer Braxton Steel’s voice boomed across the mess hall at Coronado Naval Base. His perfectly pressed…

End of content

No more pages to load