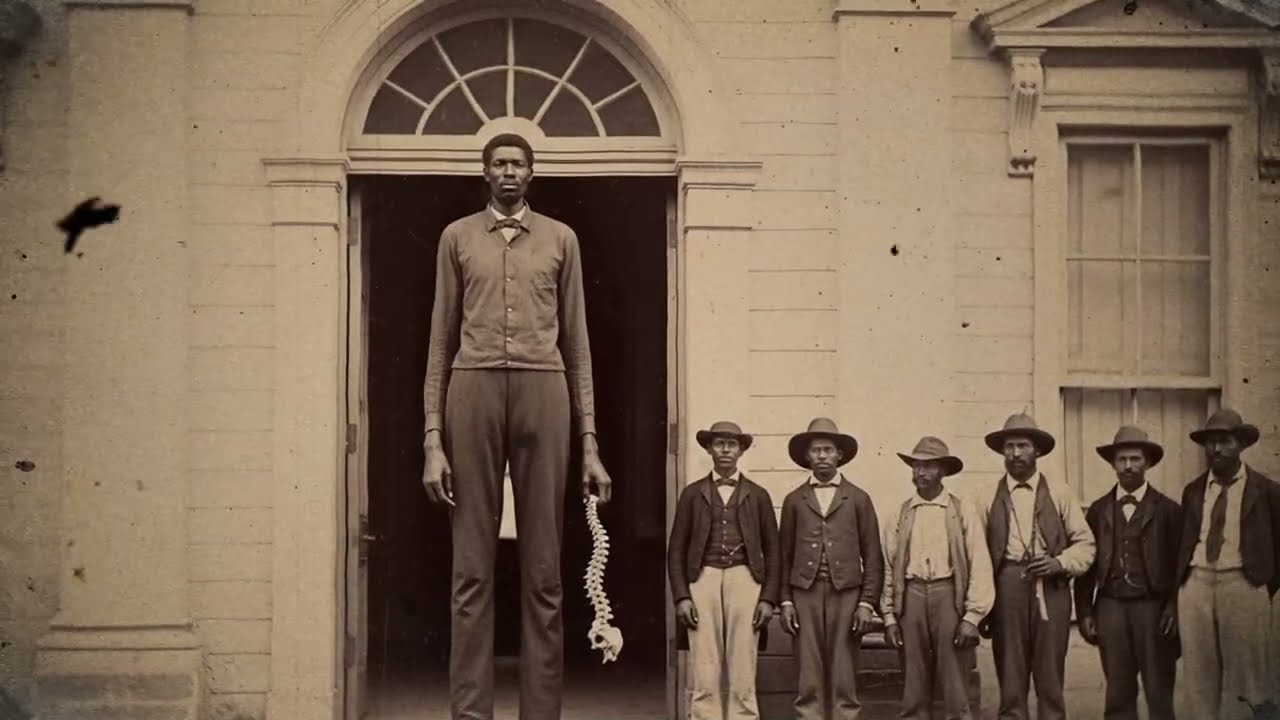

Samson’s Curse: The 7’2 Slave Giant Who Broke 9 Overseers’ Spines Before Turning 25 (Alabama, 1843)

The iron shackles cut deep into wrists that could crush a man’s skull. 7 feet and 2 in of muscle stood on the auction block in Mobile, Alabama. As the August sun beat down without mercy, the crowd fell silent. They had never seen a human being this size. Samson didn’t look at them.

He looked through them, passed them into something they couldn’t understand. Nine men would try to break him. Nine men would never walk again. This is the true story of the giant who refused to bow. Before we continue, hit that subscribe button.

This story gets darker than anything you’ve heard before, and you won’t want to miss what happens next. The mobile slave market stank of human sweat and fear on that August morning in 1843. Wooden platforms lined the waterfront where ships from the Caribbean docked weekly, bringing their human cargo. Auctioneer Marcus Thornnehill had sold thousands of enslaved people in his 20-year career.

But when the cargo door opened on the merchant vessel deliverance, even he stepped backward. Samson emerged bent nearly double through the doorway. When he straightened to his full height, women in the crowd gasped. Men reached instinctively for weapons they weren’t carrying.

His skin was darker than the Mississippi mud, stretched tight over muscles that belonged on a draft horse, not a man. Scars crisscrossed his back in patterns that told stories of previous owners who had tried and failed to break his spirit. The chains binding his wrists were naval grade iron, thick as a grown man’s thumb. His ankles bore matching restraints connected by a two-ft length of chain that forced him to shuffle rather than walk.

Despite the restrictions, despite the humiliation of standing half- naked before hundreds of gawking strangers, Samson’s eyes burned with something that made seasoned slave traders nervous. Thornhill cleared his throat and began his pitch, but his usual confidence wavered. The giant on his platform wasn’t broken.

That was a problem. Bidding started at $500, twice the going rate for a prime field hand. Plantation owners from across southern Alabama had traveled to Mobile specifically for this auction. Word had spread about the giant captured in Haiti after killing three French colonial soldiers with his bare hands.

“600,” called a voice from the back. Thomas Witmore, owner of Whitmore plantation, pushed through the crowd. He needed strong backs for the expansion of his cotton fields. “700,” countered another buyer. The price climbed steadily. “$800. 900. $1,000.” The crowd murmured. That was enough to buy three healthy field hands and still have change for a house servant.

Thornhill smiled as the bids continued. He had paid the ship captain $200 for the giant, and now he would make five times that profit. But as he looked at Samson standing motionless on the block, a cold finger of doubt traced his spine. The enslaved man’s eyes had fixed on Thomas Whitmore, and something in that gaze made Thornhill think of a predator sizing up prey. “$1,200.”

Whitmore’s voice cut through the murmurss. “Final offer. I’ll pay cash today.” The other biders fell silent. $1,200 was fortune money. Thornhill brought down his gavvel with a crack that echoed off the waterfront buildings. “Sold to Thomas Whitmore of Witmore Plantation.”

As workers moved to transfer the chains to Whitmore’s custody, Samson finally moved. He turned his head slowly to face his new owner. In the heavy silence that followed, a single word emerged from the giant’s throat, deep as distant thunder, “Remember!” Thomas Whitmore’s cotton plantation sprawled across 800 acres of Alabama soil, worked by 147 enslaved people.

The overseer position had changed hands twice in the past year. Both previous holders had quit after receiving death threats from enslaved workers who refused to be broken. Whitmore needed someone ruthless. He needed someone who understood that fear was the only currency that mattered. He needed James Rutled, a man whose reputation for cruelty had spread across three states.

What Witmore didn’t know was that Rutled had already heard about the giant. What neither of them understood was that Samson’s chains held something far more dangerous than muscle. They held mathematics, memory, and a patience that could outlast stone. The sun began its descent as the wagon carrying Samson rolled north toward Whitmore Plantation, where the first spine would break in exactly 17 days.

The wagon wheels cut deep ruts in the red Alabama clay as Samson arrived at his new prison. Whitmore plantation stretched endlessly in all directions, rows of cotton plants turning brown in the late summer heat, wooden slave quarters arranged in neat lines behind the main house, and everywhere the smell of wood smoke and human exhaustion.

James Rutled stood waiting in the yard between the main house and the quarters. He was a compact man, 5’8 in of coiled violence, with arms thick from years of wielding a bullhip. A jagged scar ran from his left eye to his jaw, a reminder from a knife fight in New Orleans that he had won by biting through his opponent’s throat. He dressed entirely in black despite the heat.

And the whip coiled at his belt had a name, Mercy. He called it that. Ironically, when Samson climbed down from the wagon, Rutled didn’t flinch at his height. He had broken bigger spirits than this, even if they came in smaller packages. 50 yards away, enslaved workers pretended to busy themselves with evening chores while watching the confrontation.

They had seen this scene play out before, new arrivals being introduced to Plantation Justice. It always ended the same way. “My name is James Rutled,” the overseer said, circling Samson slowly. “I run this plantation. Mr. Witmore owns the land and the people, but I own your waking hours, your sweat, and your blood if you make me take it. You will address me as sir.”

“You will obey every command without hesitation. You will meet your cotton quotota or face consequences. Do you understand?” Samson said nothing. His eyes tracked Rutled’s movement with the same intensity a barn cat watches a circling hawk. Rutled stopped circling. He uncoiled Mercy from his belt. The leather made a sound like a snake sliding through dry grass.

“I asked you a question, boy. When I ask questions, you answer. Now, do you understand?” The silence stretched between them like a tightening rope. Other enslaved people had stopped even pretending to work. Everyone watched. “I see,” Rutlage said quietly. “You need a lesson in respect.” The first lashing. Rutled’s arm moved with practiced precision.

The whip cut hair, then flesh. A line of blood appeared across Samson’s shoulders. The giant didn’t make a sound. Crack. A second stripe parallel to the first. No sound, crack, a third, fourth, fifth. Each strike perfectly placed to maximize pain. Rutled had given thousands of lashings in his career.

He knew exactly how to make a man scream, but Samson stood silent, his eyes never leaving Rutlage’s face. By the 10th strike, Rutlage’s breathing had grown heavy, not from exertion, but from something else. uncertainty. He had broken men with three lashes. He had reduced grown field hands to weeping children with five. This giant absorbed 10 like summer rain.

Rutled raised the whip for an 11th strike. That’s when Samson spoke for the second time since arriving in Alabama. His voice came out soft as distant thunder. “17 days.” The whip froze mid ark. “What did you say?” “17 days,” Samson repeated. “Remember the number.” Rutled’s face flushed crimson.

He delivered five more lashes in rapid succession, each one harder than the last. Blood ran down Samson’s back, pooling in the dust at his feet. But through it all, the giant never looked away, never cried out, never bent. Finally, Rutled coiled his whip. His hands trembled slightly, not from fear, but from rage.

In all his years as an overseer, no one had ever looked at him with such absolute contempt. “Take him to the quarters,” he ordered the other workers. “Get him patched up. Tomorrow he picks cotton like everyone else. If he doesn’t meet quota, we’ll continue this conversation.” The quarters that night, 10:30 to 11:30. The slave quarters consisted of 20 wooden cabins, each housing 8 to 10 people.

Samson was assigned to cabin 7, where the other field hands made room for him with a mixture of fear and curiosity. An older woman named Esther, who served as the plantation’s unofficial healer, cleaned his wounds with strips of cloth and a mixture of herbs she kept hidden in a tin box. “You shouldn’t have spoken to him,” she whispered as she worked. “Rutlage has killed men for less.”

Samson sat perfectly still despite the pain that must have been radiating through his torn flesh. “How long has he been overseer here?” “10 months. The one before him lasted only 6 months. Couldn’t handle the work.” She paused, her hands gentle on his wounds. “Couldn’t handle what Mr. Whitmore demanded. Rutled has no such weakness.”

He enjoys it. Other workers in the cabin listened in the darkness. A young man named Isaiah, barely 18, spoke up. “They say you killed three soldiers in Haiti. Is it true?” Samson’s response came after a long silence. “They were trying to separate my mother from my sisters. I was 14.” The cabin fell silent.

Everyone there had similar stories. Families torn apart, loved ones sold away, children ripped from mother’s arms. Samson’s size made him unique, but his pain was universal. The reality of what you’re hearing happened to millions of people. If this story is opening your eyes to history they didn’t teach in school, let others know by sharing this video.

The truth needs to be told. Esther finished bandaging Samson’s back and sat back on her heels. “What did you mean when you told Rutled 17 days?” Samson’s eyes gleamed in the candle light. For the first time since arriving at the plantation, something that might have been a smile crossed his face. “In Haiti, my father was a blacksmith.”

“Before the French killed him, he taught me to work metal and he taught me to count. Not just 1 2 3. He taught me mathematics. How to measure, calculate, predict, how to see patterns.” “I don’t understand,” Isaiah said. “Rutlage has a pattern. I watched him while he circled me. He favors his right leg. Old injury probably.”

“He breathes harder after exertion than a man his size should. Weak lungs. He holds his whip in his right hand, but reaches for his knife with his left. That means his dominant hand isn’t as strong as it should be. He’s hurt it recently.” “So?” another voice asked from the darkness. Samson’s smile widened, though there was no humor in it.

“So I can calculate exactly how long it will take for his patterns to create an opportunity. 17 days from now, the moon will be in the right phase. The cotton will be at the right height. He will make his usual rounds at the usual time, and his patterns will intersect with mine.” “You’re planning to run,” Esther breathed. “No,” Samson said. “Running is what they expect.”

“I’m planning something they can’t predict because they don’t think we can think. They see muscle and dark skin and chains. They don’t see mathematics.” In the darkness of cabin 7, eight enslaved people listened as a giant explained how he would break his first overseer. Not with rage, not with strength, but with the one thing the system never expected from people it considered property, superior intelligence.

The cotton fields waited in the darkness beyond the cabin walls, and in 17 days they would witness something that would change Whitmore Plantation forever. The bell rang at 4:30 in the morning, as it did every day except Sunday. Samson woke in the darkness of cabin 7, his back screaming from the previous day’s lashing. Around him, other workers stirred, bodies exhausted from yesterday’s labor, preparing for today’s suffering.

By 5:00, 147 enslaved people stood in rows before the cotton warehouse where James Rutled distributed picking sacks. Each sack had a name written in chalk on a small slate attached to it. Each slate showed yesterday’s weight and today’s quotota. The mathematics of slavery written in numbers that determined who would eat and who would bleed.

Rutled stood on a wooden platform so he could see every face. “Daily quotota is £200 per person. Anyone who comes up short answers to me personally. Anyone who exceeds quotota gets an extra ladle of stew at dinner. Anyone who refuses to work loses their food entirely.” He paused, his eyes scanning the crowd until they found Samson. “We have a new worker today.”

“He’s a big boy, so his quotota is £300. I trust that won’t be a problem.” Samson took his sack without expression. The cotton picking bag was designed for someone six feet tall at most. On him, it looked like a child’s toy, but he slung it over his shoulder and followed the others into the field as the first rays of sun broke over the horizon.

Cotton stretched in every direction, plants heavy with bowls ready for harvest. The work was simple but brutal. Grab the cotton bowl. Pull it from the plant without damaging the stem. Drop it in your sack. Move to the next plant. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. From sunrise to sunset, bent double, fingers bleeding from the sharp edges of the dried bowls, back screaming, arms aching.

For the average picker, 200 lb meant harvesting approximately 400 bowls per hour for 12 hours. It meant your fingers became mechanical extensions of your will, moving faster than thought, picking until you couldn’t feel your hands anymore.

It meant ignoring the heat, the thirst, the pain, and the knowledge that tomorrow you would wake up and do it all again. Samson began picking. His massive hands moved with surprising delicacy, plucking cotton without damaging the plants, but he worked slowly, deliberately slowly. By noon, his sack was barely one-third full. Other workers glanced at him nervously. They knew what was coming.

Rutled made his rounds on horseback, checking the progress of his workers. He carried a leather ledger where he recorded weights and made notes about who would face punishment. When he reached Samson’s row, he dismounted and walked through the cotton plants to where the giant picked. “Show me your sack.”

Samson straightened to his full height, dwarfing the overseer. He held out the picking bag. Rutled grabbed it, hefted it, and his face darkened. “This is maybe 60 lb. You need 240 more before sunset. You’re not even trying.” “The work is new,” Samson said carefully. “Tomorrow will be better.” “Tomorrow,” Rutled’s hand moved to his whip.

“You think you can negotiate with me? You think you can decide when you work hard and when you don’t?” A crowd was forming. Workers from adjacent rows had stopped picking to watch. They had all been in Samson’s position before, falling short of quota, facing Rutled’s wrath. Learning that resistance only made things worse.

They watched the giant to see if he was truly different or just another man who would break. Rutled uncoiled Mercy. “Strip off your shirt. You’re going to learn what happens to lazy workers on this plantation.” Samson didn’t move. His eyes fixed on something beyond Rutled’s shoulder. Calculating, measuring, planning. “I will meet my quotota,” he said.

“But I need something first.” The overseer’s laugh was sharp as broken glass. “You need something, boy? You don’t need anything except to learn your place. Now strip or I’ll have five men hold you down while I whip you bloody.” “I need water,” Samson continued as if Rutled hadn’t spoken.

“The other workers have buckets at the end of each row. I have nothing. Give me water and I’ll pick 300 before sunset.” Rutled’s face flushed crimson. Several workers held their breath. No one negotiated with James Rutled, but after a long moment, the overseer’s lips twisted into something resembling a smile. “Fine.”

“You want water? You’ll have water. But if you come up even one pound short of 300, I’ll give you 50 lashes instead of 10. Do we have a deal?” “We have a deal,” Samson said. A bucket of water appeared at the end of Samson’s row, brought by a house servant who looked at the giant with wide, fearful eyes. Samson drank deeply, then returned to picking. But something had changed.

His hands moved faster now, not frantically, but with mechanical precision. He had been studying the other pickers all morning, watching their techniques, calculating the most efficient method. Cotton bowls dropped into his sack in a steady rhythm. Row by row, he moved through the field. Other workers noticed the change.

Isaiah, picking in the adjacent row, watched in amazement as Samson’s massive hands plucked cotton at a speed that seemed impossible for someone his size. By 2:00, Samson’s sack was half full. By 3:00, it hung heavy on his shoulder. By 4:00, he was dragging it behind him because it had become too heavy to carry. Rutled rode by twice, each time checking the sacks weight with increasingly surprised expressions. But Samson wasn’t just picking cotton.

He was counting. Every bowl represented approximately 4 oz. 75 bowls per pound. 300 lb meant 22,500 bowls. He had been tracking his progress with mathematical precision since receiving his water, adjusting his speed to ensure he would hit exactly 300 lb, not 1 ounce more, not 1 ounce less.

As the sun began its descent toward the horizon, Samson plucked his final bowl. He tied off his sack and dragged it toward the cotton scales near the warehouse. A crowd had formed. Word had spread that the new giant might actually meet Rutled’s impossible quota. Rutled stood beside the scales, his ledger open. One by one, workers brought their sacks to be weighed.

Most hid their quotas. A few fell short and received check marks in the ledger. Promises of punishment to come. When Samson’s turn arrived, the overseer’s smile was predatory. “Let’s see if you’re as smart as you think you are.” Two workers helped lift Samson’s sack onto the scale.

The counterweight dropped, steadied, then settled. Rutled leaned in to read the measurement. His smile faded. He checked the weight again, adjusting the counterbalance to be certain. “300 lb,” he said slowly. “Exactly 300 lb,” the watching crowd murmured. Meeting quotota was expected. Meeting it exactly was impossible. Cotton wasn’t that precise. bowls varied in size. Moisture content affected weight. The scales themselves had a margin of error.

Yet somehow this giant had calculated down to the ounce. Samson met Rutled’s stare without expression. “Tomorrow I’ll do 350.” The overseer’s hand went to his whip, then stopped. Around them, workers watched in silence. For the first time in his 10 months at Witmore Plantation, James Rutled felt something he hadn’t experienced in years. Uncertainty.

This giant wasn’t like the others. This giant was thinking several moves ahead. The mathematics of oppression met something unexpected. Mathematical genius. This is just the beginning of how Samson turned the systems own tools against it. Stay with us. “Get to your quarters,” Rutled finally said.

His voice had lost its edge of confidence. “All of you. Tomorrow’s another day.” As the workers filed away toward their cabins, Isaiah walked beside Samson. “How did you know the exact weight?” Samson’s response came quietly. “I counted every bowl. 75 per pound time 300. But I also added an extra 20 bowls to account for moisture loss during the day and scale variance. Mathematics doesn’t lie, people do.”

Behind them, James Rutled watched the giant disappear into the gathering darkness. He made a note in his ledger beside Samson’s name. Dangerous. Monitor closely. Break if necessary. 16 days remained until the first spine would crack.

James Rutled had broken men’s bodies for two decades, but he had also learned to break their minds. Over the next week, he deployed every psychological weapon in his arsenal against Samson. Day three, Rutled assigned Samson to work alone in the furthest cotton field, half a mile from other workers. Isolation was a weapon, but Samson worked without complaint, his sack filling with mechanical precision, his mind calculating, counting down the days. Day five, Rutlidge cut Samson’s food ration in half.

The other workers watched as Samson received watery corn mush, barely enough to sustain a child, let alone a 7-ft giant doing brutal labor. But Samson ate slowly and somehow maintained his quota. Workers began slipping him portions of their own meals when overseers weren’t watching. Day seven, Rutlidge ordered Samson to work through Sunday rest.

While others rested, Samson picked cotton alone under the brutal sun. But through it all, the giant never complained. Every night he would announce the countdown. “13 days,” then “12 days,” then “11.” On the eighth night after Samson announced “nine days,” Esther finally asked, “What happens in nine days?”

Samson sat with his back against the cabin wall. “Rutled makes his rounds every day at the same times. 4:30 wake up. 6:00 first inspection. 9:00 midm morning check. Noon lunch. 3:00 afternoon rounds. 6:00 weighing. 8:00 cabin inspection. He never varies. Not by five minutes. People who rely on routines become predictable.” “But what good does that do?” Another worker asked. “He’s armed. He has dogs.”

“I won’t attack him,” Samson said. “I’ll let him attack me, but on my terms, not his.” The conversation was interrupted by boots on the cabin steps. The door swung open. Rutled stood silhouetted against the moonlit yard. “I heard talking. Who was speaking?” Samson’s voice emerged from shadows. “I was praying.”

Rutled stepped inside. “Praying out loud after curfew.” “The Lord doesn’t observe curfew, sir.” The overseer’s jaw clenched. He couldn’t punish prayer without contradicting plantation policy. “Since you’re so devoted, you can pray tomorrow while working an extra row. 350 lb quotota.” “Yes, sir.” Rutled lingered, his eyes moving from face to face.

“9 days until what?” The silence stretched tight. “9 days until Sunday,” Samson replied. “I was praying that God grants me strength to endure nine more days until the Sabbath rest.” The overseer stared, then walked away. Only when the sound faded did anyone breathe. “He knows you’re planning something,” Esther whispered urgently. “Good,” Samson said. “Let him watch.”

“People who watch closely miss what’s happening at the edges of their vision.” On the 11th day, 6 days before Samson’s predicted convergence, Rutled made his move. At the afternoon weighing, Samson dragged his sack to the scales. £350, exactly as ordered, but Rutlidge smiled. “According to my ledger, you were supposed to pick £400 today.”

Samson’s face remained expressionless. “You said 350.” “Did I?” Rutled opened his ledger showing £400 written in fresh ink. “See £400. You’re £50 short.” Workers had gathered to watch. Everyone knew what was happening. Rutled was manufacturing a reason to punish Samson publicly. “You changed the number,” Samson said quietly.

“Are you calling me a liar, boy?” The challenge hung in the air. Either way, Rutled one. Samson looked at the overseer, and then smiled. “No, sir. I must have misheard. My mistake. I’ll accept the punishment I’ve earned.” Rutled’s smile faded. He had expected resistance. “Strip your shirt. 50 lashes. Everyone watches.”

As Samson removed his shirt, revealing scars of previous punishments, he caught Isaiah’s eye. His lips moved silently. “5 days.” The first lash fell. Samson didn’t make a sound. By the 20th, watchers had turned away. By the 30th, Esther wept openly. By the 40th, even overseers looked uncomfortable. By the 50th, Rutled was breathing hard, his weak lungs struggling.

The giant hadn’t broken, hadn’t screamed, hadn’t begged. “Get him cleaned up,” Rudlage ordered, his hands trembling. “Tomorrow’s quota is £400.” As workers carried Samson toward the quarters, the overseer stood alone in gathering darkness, feeling something cold in his chest. Not guilt, but uncertainty. He might have misjudged his opponent.

In cabin 7 that night, Esther tended Samson’s wounds while he whispered through gritted teeth, “5 days. His pattern is almost complete. Desperate men make mistakes. Five more days.” Samson’s back was torn flesh. But when the bell rang, he rose with the others. Each step was agony. Yet Samson walked to the warehouse, took his sack, and listened as Rutled announced, “400.”

“No exceptions.” £400 meant 30,000 cotton bowls. For someone played raw less than 24 hours ago, it was effectively impossible. Everyone knew it. But Samson picked up his sack and walked into the fields. Each movement pulled at wounds across his back. Each bend sent lightning through his body.

By 6:00, his shirt was soaked with blood and sweat, but his hands kept moving. 75 bowls per pound. 400 lb, 30,000 bowls, 12 hours, one every 1.4 seconds. The mathematics were clear. The pain was irrelevant. By noon, Samson’s sack was barely 1/3 full. Rutled checked the weight, his smile genuine. “Maybe 120 lb. You need 280 more by sunset. Looks like we’ll be having another conversation this evening.”

Samson said nothing. His entire existence had narrowed to a single focus. Hand to plant, pull cotton, drop in sack, move to next. The pain became white noise. He acknowledged but didn’t obey. At 4:00, Isaiah made a decision. He finished his own row early, then moved into Samson’s field and began picking.

10 minutes later, Sarah appeared with an empty sack and began picking. Then Marcus arrived. Within 30 minutes, seven people were picking cotton in Samson’s rose, their hands moving in silent coordination. Rutled noticed before sunset. He rode into the field at full gallop, his face crimson with fury. “What is this? What are you doing in his rose?” Isaiah straightened.

“Helping, sir. He’s injured. We finished our quotas early.” “You thought?” Rutled’s whip came off his belt. “You don’t think, you obey. Everyone who picked in his rose, drop your sacks. You’re all getting 10 lashes.” Samson finally spoke. “No.” Rutled turned slowly. “What did you say?” “They were following my orders.”

“I asked them to help. If anyone gets punished, it should be me.” “You’ll all be punished. Every single one of you will.” “400 lb.” Samson interrupted, pointing to his bulging sack. “Weigh it right now. If it’s 400 lb, you leave them alone. If not, add their lashes to mine.” Rutled’s eyes narrowed. “Fine.”

“If you’re short, even £1, everyone here gets 20 lashes, including you.” They brought scales into the field. Workers from other sections stopped to watch. Even Thomas Whitmore emerged from the main house. The afternoon sun cast long shadows as four men lifted Samson’s sack onto the scales. The counterweight dropped, settled. The needle wavered, then stopped. 43 lb.

Rutled stared in disbelief. “That’s impossible.” “Mathematics doesn’t care about conditions,” Samson replied. “I picked 280 lb. Isaiah picked 40. Sarah picked 35. Marcus picked 28. The others added 60. 280 + 120 = 400 plus 3 lb margin of error. 403 total.” He had calculated it exactly.

Despite pain, despite chaos, he had mathematically coordinated seven people’s labor to hit his quota precisely. Whitmore stepped forward. “Mr. Rutled, a word.” The two men walked away and spoke in low tones. Finally, Witmore addressed the crowd. “What happened today will not happen again. Anyone caught picking in another’s rose will be sold immediately. But today’s quotota was met. No punishment. Return to duties.”

As the crowd dispersed, Rutlidge caught Samson’s arm, his grip iron tight. “You think you’re smart, but I’ve broken bigger men. Whatever you’re planning for 4 days from now, I’ll be ready. When it comes, I’ll make sure it’s the last thing you ever do.” Samson looked down at the overseer, and for the first time, his expression showed pity. “4 days, sir.”

“Remember the number.” That night, as Esther tended wounds that should have killed a normal man, Samson whispered, “For days, he’s watching me now. Watching closely, exactly as planned. When you want to hide something, you make people look directly at it. They see what they expect and miss everything else.” “What are they missing?” Isaiah asked.

Samson’s smile was visible in dim candle light. “They’re watching me. No one’s watching him.” Samson worked his quotas for 3 days without incident. 300 lb each day. Not a bowl more, not less. His wounded back slowly healed. The plantation settled into brutal routine, but beneath the surface, tension grew. Rutled increased surveillance.

He rode through fields every hour instead of every three. He conducted surprise cabin inspections at random times, but the harder he looked, the less he saw. The network around Samson operated in silence, in glances, in moments too brief to catch. Day 13. Samson asked Isaiah during a water break, “When Rutled walks through fields, which leg does he favor?” Isaiah thought. “His right.”

“He limps slightly.” Day 14. Sarah reported a conversation she overheard between Whitmore and his wife. “Mr. Whitmore thinks workers are deliberately slowing pace. He told Rutled to increase discipline.” Day 15. Old Marcus shared an observation. “The chestnut mare Rutled rides. She’s skittish around snakes. Last week, a garden snake crossed the path and nearly threw him.”

Samson absorbed each piece without comment. His mind was a map now, charting physical locations, temporal patterns, psychological vulnerabilities, environmental factors. Every variable contributed to an equation that would resolve in 2 days. On the night of day 15, Samson gathered seven people in cabin 7 after curfew. The risk was enormous, but the time had come.

“In 2 days, at 3:00, Rutled will conduct rounds through eastern cotton fields. He’ll be riding his mayor. Temperature will be mid90s. He’ll be tired. His weak lungs will struggle in the heat. That’s when the pattern completes.” “What pattern?” Esther asked. Samson spread his hands like chess pieces. “Every system has weak points.”

“Rutledge is the enforcement mechanism of this plantation. Remove him and the system destabilizes. But you can’t just attack that leads to execution. So you make him remove himself.” “I don’t understand.” Sarah whispered. “Mathematics can predict outcomes with enough variables. I’ve collected them for 15 days.”

“Tomorrow we arrange them. The day after they interact and the equation solves itself.” “What do you need?” Isaiah asked. “Tomorrow morning, Marcus, find a water moccasin near the creek. Don’t kill it. Trap it in a sack and hide it in the tool shed near Eastern Fields.” “That’s a death sentence if I’m caught,” Marcus protested. “You won’t be.”

“Overseers never inspect the tool shed on Saturdays, their lightest supervision day. You’ll have a 3-hour window. Sarah tomorrow mentioned to Mrs. Whitmore that workers in Eastern Fields complained about loose fence posts. Make it casual. She’ll tell Mr. Whitmore, who will tell Rutled to inspect Eastern Fields on afternoon rounds.”

“Isaiah, you’re going to pick in the row adjacent to mine. At exactly 2:45, collapse from heat exhaustion. Not fake, actually. Collapse. Don’t drink water.” “That’s dangerous,” Esther interrupted. “People die from heat stroke.” “Not if someone is there with water within 5 minutes, which you will be, Esther. You’ll deliver afternoon water to that field.”

“You’ll revive Isaiah and Rutled will have to dismount to check him. Plantation policy. That’s when his horse will be vulnerable.” Marcus spoke. “You’re going to spook his horse with the snake.” “Yes, his right knee is weak. A fall from horseback onto that knee could injure him severely, possibly permanently.” Day 16. The execution.

28 col 40 30 col 0 0 Saturday dawned hot and humid by 9:00 temperature had climbed to 92° by noon 97 Marcus found his water moccasin at 11:30 4 ft long brown and thick with a distinctive flathead marking it as one of Alabama’s most dangerous serpents he trapped it and carried it to the tool shed not a single overseer looked his direction.

He hid the sack beneath old cotton sacks and walked away, heart hammering but face calm. Sarah spoke with Mrs. Whitmore at 12:15, mentioning loose fence posts in the exact casual tone Samson had coached. Mrs. Whitmore thanked her and immediately told her husband.

Whitmore summoned Rutlidge at 12:30 and ordered him to inspect eastern field fences during afternoon rounds. By 2:00, all pieces were in position. Samson worked his row. Isaiah worked adjacent, deliberately, not drinking since noon, despite brutal heat. Esther prepared water buckets. Marcus worked close enough to see, but far enough to avoid suspicion.

At 2:15, Isaiah began feeling symptoms. Dizziness, confusion, fatigue. At 2:30, he collapsed exactly as planned because the mathematics of dehydration and heat were as reliable as any physical law. Esther saw him fall. She ran with water calling for help. Workers converged. Someone fetched the overseer. At 2:45, Rutlidge arrived on his mayor. He dismounted to check Isaiah.

Annoyance on his face. Another weak worker. too lazy to drink properly. While Rutled examined Isaiah, Samson moved with precision. He walked to the tool shed ostensibly for more equipment and retrieved the burlap sack. The moccasin inside was agitated from hours in heat. Samson carried it back, timing his approach to coincide with Rutled remounting. “Mr. Rutled, sir, I found something you should see.”

The overseer, back in his saddle, turned. “What is it, boy?” “A loose fence post, just like Mr. Whitmore wanted you to inspect. Dangerous. Looks like it might collapse.” Rutled urged his horse toward Samson. Irritation clear. “Show me.” Samson walked toward fence 20 ft away. Rutled followed.

They reached the fence and Samson pointed to a perfectly secure post. “This one, sir, that post is fine. Are you wasting my time?” “My mistake. Must have been this one.” Samson moved along the fence, leading Rutled’s horse further from other workers. When isolated, Samson made his move. In one fluid motion, he opened the sack and flung the water moccasin toward ground directly in front of the mayor.

The snake landed coiled and ready. Its triangular head rose, detecting the massive warm creature above. The mare saw the serpent and reacted with pure terror. She reared violently, screaming, her hooves pouring air. Rutled caught off guard tried to maintain his seat but his weak knee couldn’t grip.

His damaged hand couldn’t hold rains with sufficient strength and his compromised lungs left him gasping instead of bracing. He fell backward, body twisting to protect himself. The impact was catastrophic. Rutled’s right knee struck ground first, bending at an angle nature never intended.

The sound of breaking bone was audible even over the mayor’s panic. The overseer’s scream followed, high-pitched, agonized, utterly human. He collapsed into red Alabama dust, clutching his shattered knee. All authorities stripped away in an instant. Workers came running. Samson was already moving toward Rutlage. Face a mask of concern. “Mr. Rutled. Sir, are you injured? I tried to warn you about the snake. It must have been hiding near the post.”

Through gritted teeth, Rutled managed. “You… You did this… planned.” “I found a snake, sir. I was showing you the dangerous post, just like Mr. Witmore ordered. The snake must have been attracted to shade. Someone get the doctor. Mr. Rutledge has been thrown.” Thomas Witmore arrived within minutes.

He found his overseer writhing in dust, right knee bent at an obscene angle, bone fragments visible through torn flesh. The mayor had bolted. A 4-ft water moccasin slithered away through cotton plants. “What happened?” Whitmore demanded. Multiple voices. “A snake spooked his horse. Mr. Samson was showing him fence posts.”

“The mayor threw him. It was an accident.” Whitmore looked at Samson, suspicion flickering. But what could he prove? The giant stood with appropriate concern, hands empty. Story corroborated by half a dozen witnesses. A snake had appeared. Common in Alabama cotton fields. A horse had been spooked. Happened regularly. An overseer had fallen. Tragic, but hardly unprecedented.

“Get him to the house,” Whitmore ordered. “Send for Dr. Harrison. You back to work. All of you.” As workers dispersed, Isaiah caught Samson’s eye for a fraction of a second. The giant’s expression never changed, but in that brief glance, an entire conversation occurred. The mathematics had been perfect. The pattern had completed exactly as calculated.

The first spine had broken. That night, Dr. Harrison delivered his diagnosis. Rutled’s right knee was shattered beyond repair. The kneecap had fractured into seven pieces. Even with best medical care available in 1843 Alabama, Rutled would never walk normally again. His days as overseer were finished.

In cabin 7, Samson spoke one word to the darkness. “One,” the count had begun. Rutled spent three weeks in the main house, his shattered knee bound in splints. Dr. Harrison visited daily, administering Ldinum for pain. The prognosis never improved. Rutled would walk with a cane for life in constant pain.

Whitmore needed a replacement immediately. 800 acres didn’t oversee themselves. Word went out. Whitmore plantation required an experienced overseer, top wages, immediate start. Within a week, three candidates arrived. Whitmore chose Marcus Webb, a man whose reputation for cruelty exceeded even Rutled.

He was rumored to have killed two people with his bare hands and faced no legal consequences. Web started on a Tuesday morning, exactly 25 days after Rutled’s fall. The plantation’s population watched him with careful eyes, measuring, calculating, waiting. Marcus Webb was 6 feet tall, 220 lb of muscle, with a face carved from granite. He carried two weapons, a bullhip called discipline, and a loaded pistol he made no effort to conceal.

His first action was to gather all 147 workers in the yard. “My name is Marcus Webb,” the new overseer announced. “I know some of you think you’re clever. I know what happened to Mr. Rutled. An accident with a snake. Very convenient. Very fortunate timing for certain people.” His eyes swept the crowd and stopped on Samson. “You… front and center.”

Samson walked through the parted crowd until he stood before Webb. The height difference was dramatic. Samson towered over Webb by 14 in, but Webb showed no intimidation. “I’ve heard about you, the smart one, the mathematical genius. Very impressive.” His tone made clear he was not impressed. “Here’s what you need to understand.”

“I don’t care how smart you are. I care about obedience. When I give an order, you follow instantly. If you hesitate, you bleed. If you refuse, you die. Do we understand each other?” “Yes, sir.” “Good. Your daily quotota is now £500. You’re a big boy. You should handle big numbers. If you come up short, I’ll make Rutled’s punishments look merciful. Now get back in line.”

Web addressed the group again. “New rules start today. Daily quotas increase 10% across the board. Anyone who falls short three times in a week loses Sunday rest. Anyone who causes trouble disappears. I don’t do public punishments. Too theatrical. When I discipline someone, it happens privately and they either learn or they don’t come back.”

“Questions.” Silence. “Excellent. Get to work.” Marcus Webb was different from Rutled in ways that made him more dangerous. Rutled had been predictable. Patterns, schedules, rules. Web was chaos. He appeared at random times. He conducted surprise inspections at 3:00 in the morning. He changed quotas without warning. He rewarded compliance with suspicion and punished failure with disappearance.

In the first week, two workers vanished. One was Thomas, who had questioned a quotota increase. The other was Ruth, caught stealing food. Neither was seen again. When asked what happened, Webb simply said, “Sold to a plantation in Mississippi. If you don’t want to join them, work harder.”

But people who had contacts on neighboring plantations heard no word of Thomas or Ruth arriving anywhere. Whispers began. Whispers that Web hadn’t sold them at all, that their bodies were buried somewhere in the woods. Whispers that couldn’t be proven but felt true. Samson worked his 500 lb quotota without complaint. He met it exactly every day using mathematical precision.

But now he worked alone. No one helped him. No one spoke to him. No one looked in his direction too long. Webb had made clear that association with the giant was dangerous. What no one knew was that Samson barely slept. While others rested during precious hours between sunset and the 4:30 bell, Samson watched.

His cabin was positioned at the rose end with a small gap between wooden planks offering a view of the overseer’s house, main house, and paths between buildings. Night after night, Samson observed. He saw Web emerge from his quarters at 11:00 and walked to the tool shed near the cotton warehouse. He saw the overseer carry a lantern and shovel.

He saw Webb return 2 hours later without the shovel, boots caked in fresh mud. He saw the pattern. Every third night, same routine, same timing, same direction. On the 20th day of Web’s employment, Samson finally understood the disappeared workers weren’t sold. They were buried and Webb was visiting the graves every third night to ensure they remained concealed.

It was a pattern born from paranoia and guilt. The overseer checking his crimes, making certain no evidence had surfaced. In cabin 7, as October began to turn Alabama nights cooler, Samson whispered his plan to the darkness. Not to Isaiah or Esther or Marcus, just to himself, rehearsing the mathematics that would seal Web’s fate.

The equation was more complex this time involving more variables, more risk, more precision. But Samson had learned something important. The system believed he was property incapable of sophisticated thought. That belief was his greatest advantage. On the 21st day of Marcus Webb’s employment as overseer, the giant began the sequence that would break the second spine.

This time the breaking would come not from violence, but from a revelation that would force Whitmore to confront what kind of monster he had hired. The mathematics of justice were accelerating. Samson needed proof. On a moonless October night, while Webb made his routine patrol of burial sites, Samson slipped from cabin 7.

The plantation slept around him as he moved through shadows, his massive frame somehow silent. He reached the tool shed where Webb stored his shovel and found it unlocked. The overseer’s arrogance assumed no one would dare investigate. Inside, Samson found more than tools. A leather ledger sat on a shelf hidden beneath burlap sacks. He opened it by carefully shielded candle and began to read. What he found confirmed his suspicions and revealed something worse.

Marcus Webb kept meticulous records, not of cotton quotas, but of murders. 17 names spread across three plantations over 5 years. Thomas and Ruth were the most recent, but there were 15 others. People who had questioned Web’s authority, failed to meet impossible quotas, or simply looked at him wrong.

Each entry included a date, location, and brief note about disposal method. Samson’s hands trembled, not from fear, but rage. 17 people, 17 families destroyed. 17 murders that would never be investigated because victims were considered property, not people. But the ledger was evidence, and evidence could be weaponized if used correctly. He couldn’t take the ledger. Web would notice immediately.

But Samson had learned to read and write in Haiti before his capture, skills he had carefully hidden. He spent 30 minutes copying key passages onto cloth torn from his shirt, his handwriting cramped and precise in dim candle light. Names, dates, locations. When finished, he returned the ledger to its hiding place, left the shed exactly as found, and disappeared into night. The copied evidence wasn’t enough.

Samson needed corroboration, details only someone with direct knowledge could provide. Over the next week, he began careful conversations with workers from other plantations. These happened in the margins of Sunday trading when people from different properties gathered at the county market to sell vegetables from small personal gardens.

At the market, Samson found Clara, who had worked at Web’s previous plantation in Mississippi. She confirmed three workers had disappeared during Web’s tenure. Two men and a woman, all officially sold, but never heard from again. She also provided a crucial detail. Webb had a distinctive knife with a bone handle he had used to threaten workers.

The knife had belonged to his father, and Webb never went anywhere without it. Samson also spoke with Jacob, who had survived Webb’s discipline at a Georgia plantation. Jacob bore scars across his back forming a pattern, deliberate cuts spelling example. Web had carved it into his flesh as warning.

Jacob had only survived because the plantation owner had intervened, disturbed by excessive cruelty, even by slavery’s brutal standards. Each piece of information was a variable in Samson’s equation. He was building a case not for a legal system that would never prosecute a white man for killing enslaved people, but for a different trial, one that would take place in Thomas Whitmore’s ledgers and conscience.

Because while Witmore profited from human suffering, he was also a businessman. And Marcus Webb represented a liability that could destroy everything Whitmore had built. Samson needed an intermediary, someone who could bring information to Whitmore without raising suspicions about the source. He chose Sarah, the house servant who had helped with the Rutledge operation.

She had access to Whitmore’s study, his correspondence, and most importantly, his ear. On a cold November morning, Samson gave Sarah the cloth containing copied ledger entries. He explained exactly what she needed to do and when. The timing had to be perfect. If Webb discovered the leak before Witmore could act, everyone involved would die.

Sarah waited until a Tuesday afternoon when Witmore was reviewing account books in his study. Webb was making rounds in Eastern Fields miles from the main house. Sarah entered to deliver afternoon tea and deliberately dropped the tray. as she apologized profusely and cleaned the mess, she accidentally left the cloth near Whitmore’s desk. Partially hidden beneath papers where he would find it within the hour, but not immediately suspect it had been planted.

Whitmore discovered the cloth at 4:00. He read the cramped handwriting once, then again, his face growing increasingly dark. He summoned his wife and asked if anyone had entered his study. She confirmed only Sarah. Witmore called for Sarah and questioned her sharply. The house servant maintained perfect composure.

She had found the cloth in laundry and assumed it was Mr. Witmore’s handkerchief, so she returned it to his study. She apologized for not mentioning it directly. The explanation was plausible enough that Witmore dismissed her. But now he held a document listing 17 murders, including two people who had disappeared from his own plantation under circumstances he had found suspicious.

If the information was accurate, his overseer was a serial killer who had brought lethal liabilities to Witmore plantation. Over the next 3 days, Witmore conducted his own investigation. He sent letters to owners of Web’s previous plantations inquiring about workers who had been sold. Responses confirmed the cloth’s accuracy.

Multiple workers had disappeared under Web’s watch, always officially recorded as sold, but never documented arriving at new properties. Whitmore also examined his own ledgers. Thomas and Ruth had been marked as transferred to Mississippi contractor with payment recorded from a buyer whose name matched no one in Whitmore’s business network. The transaction was fabricated. Webb had created false paperwork and pocketed money that didn’t exist.

But the most damning evidence came when Witmore followed Webb on one of his nighttime walks. On a Thursday night in late November, the plantation owner watched from distance as his overseer walked into woods beyond cotton fields. Carrying a lantern and his distinctive bone-handled knife, Witmore followed carefully, staying far enough back to avoid detection.

He watched Webb kneel beside disturbed earth, check something in the ground, then cover it again with fresh soil and leaves. After Webb returned to his quarters, Witmore approached the site with his own lantern. He didn’t dig. He didn’t need to.

The evidence of disturbed earth, the size and shape of the depression, the smell that rose faintly from ground, all confirmed what the cloth had stated. This was a grave, one of several hidden in these woods. Whitmore returned to his house before dawn, his mind racing through calculations that had nothing to do with cotton and everything to do with protecting his business interests.

Web had to go, but removal had to be handled carefully. If word spread that Whitmore Plantation employed a murderer, property values would plummet. Insurance would be denied. Legal complications could tie up finances for years. But before Witmore could act, Samson made his next move. Because the giant had calculated something the plantation owner hadn’t considered, Marcus Webb wouldn’t go quietly.

Men who murdered 17 people didn’t respond to termination with resignation. They responded with violence and that violence properly directed would solve multiple problems simultaneously. On the 47th day of Web’s employment, Samson whispered to Isaiah during midday water break, “3 days Webb will learn he’s being investigated. When he does, he’ll come for me.”

“And when he comes, he’ll make a mistake.” “How do you know he’ll come for you?” “Because I’m going to tell him I’m the source. I’m going to make him so angry, he can’t think straight. Angry people don’t calculate, they react. And reactions can be predicted.” The revelation 38 col 0 0 39 col 0 0 Whitmore summoned Webb to his study on a Friday morning.

The meeting was brief and brutal. Whitmore laid out everything. The ledger entries, the verified disappearances, the graves in the woods, the fabricated transactions. Webb denied nothing. He sat in silence as his employer detailed crimes that would have resulted in hanging if victims had been white. “You’re finished here,” Whitmore concluded.

“You have 24 hours to leave my property. I’ll provide 2 months wages and a letter of reference that makes no mention of these activities, but only if you leave quietly. If you cause problems, I’ll turn this evidence over to the sheriff and let a court decide whether killing enslaved people qualifies as destruction of property.”

Web’s face remained expressionless, but his hands gripped the chair arms with enough force to make would creek. When Witmore finished, the overseer stood slowly. “Someone gave you that information. Someone snooped where they shouldn’t have. Who was it?” “That’s not your concern.” “It’s very much my concern. I don’t leave loose ends.”

“You’ll leave my property by tomorrow noon or I’ll have you arrested. That’s not negotiable.” Webb walked toward the door, then paused. “It was the giant, wasn’t it, Samson? I’ve seen how he watches everything, calculates everything. He’s the only one smart enough to piece together what I was doing.” Whitmore said nothing, but his silence was confirmation.

Webb smiled, a cold expression holding no humor. “I’ll be gone by noon tomorrow, but I’m going to have a conversation with your mathematical genius first. One last piece of business.” “You touch him and our agreement is void,” Witmore warned. “I won’t touch him,” Webb lied. “Just a conversation, man to man.”

Webb found Samson in the furthest cotton field at 2:00 that afternoon. The overseer had dismissed other workers early, claiming he needed to conduct a special inspection. Now the field was empty except for them, a 7’2 giant and a 6-ft killer surrounded by cotton plants rising to chest height, providing perfect concealment from distant observers. “You’re a clever boy,” Webb said conversationally as he approached.

His right hand rested on the pistol at his belt. His left gripped the bonehandled knife. “Clever enough to find my ledger. Clever enough to copy it. Clever enough to get it to Witmore without revealing your involvement. Very impressive.” Samson stood motionless, his picking sack half full beside him, his massive hands empty.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, sir.” “Don’t insult me with lies. We both know what you did. I respect it, actually. Takes real intelligence to expose someone like me. But here’s the problem. I can’t let you live. You’re the only witness who can connect me to those graves.”

“Once you’re gone, it’s just Whitmore’s word against mine, and he won’t risk the publicity of a trial.” “Mr. Whitmore told you to leave,” Samson said carefully. “If you kill me, you’ll hang.” Webb laughed. “Will I? Who’s going to testify against me? The enslaved workers who saw me visit this field. They can’t testify in court. The law doesn’t allow it.”

“Whitmore, who specifically let me go with a reference letter. He becomes complicit if he admits he knew about murders and did nothing. No boy, I can kill you right here, bury you in those woods with the others, and be in Mississippi by Sunday. No one will stop me.” He drew his pistol. “Turn around. I’ll make it quick. That’s more mercy than you’ve earned, but I don’t enjoy suffering.”

“I’m practical about killing.” Samson didn’t turn. Instead, he took one step forward. “You made three mistakes.” Web’s finger tightened on the trigger. “Really? What mistakes?” “First, you assumed I worked alone. I didn’t. Second, you assumed this field was empty. It’s not. Third, you assumed I was afraid of you. I’m not.”

Thomas Whitmore emerged from cotton plants 20 ft to Web’s left, a rifle raised to his shoulder. Sheriff Benjamin Crawford appeared to Web’s right, also armed. Behind Samson, two deputy sheriffs stepped into view. The overseer was surrounded, and his pistol, still pointed at Samson, became evidence of attempted murder. “Put the gun down, Web,” Sheriff Crawford ordered.

Slowly, Webb’s face cycled through emotions: surprise, anger, calculation. He was trapped. But men who had killed 17 people didn’t surrender easily. His pistol swung toward Whitmore instead of Samson. If I’m going to hang anyway, Samson moved with shocking speed. His massive hand clamped onto Web’s wrist, squeezing with enough force to shatter bone.

The pistol fired, but the shot went wild, burying itself in cotton plants. Webb screamed and tried to bring his knife around with his left hand, but Samson’s other hand caught that wrist, too. The giant lifted Web completely off the ground, holding him suspended like a child. “Drop the knife,” Samson said calmly.

Web’s hand spasmed, and the bone-handled knife fell into red Alabama dirt. Samson lowered the overseer back to ground, but didn’t release his wrists. Sheriff Crawford and deputies moved in quickly, applying iron shackles to Web’s arms and legs. Only then did Samson let go, stepping back to reveal the full extent of the trap that had been sprung.

“How?” Web gasped, his face gray with pain from his shattered wrist. “How did you know I’d come for you?” “Mathematics,” Samson replied. “You’re predictable. You’ve killed 17 people using the same pattern. Isolate them. Eliminate them. Hide them. You couldn’t let me live knowing what I knew. So, I made sure everyone else knew, too. Mr. Whitmore, the sheriff, the deputies, they all heard you confess to murders and threatened to kill me. Now, the law can’t ignore it.”

Whitmore lowered his rifle, his expression complicated. He had spent the previous day coordinating with Sheriff Crawford, explaining that his overseer was a murderer who posed a threat to witnesses.

The sheriff had been skeptical until Whitmore showed him the copied ledger entries and offered to testify about the graves. With a white plantation owner willing to testify, the law suddenly had jurisdiction over crimes it would normally ignore. Sheriff Crawford secured Web in a wagon for transport to county jail. The trial would be brief. Attempted murder of Thomas Whitmore in front of witnesses was enough to hang him, even without addressing the 17 enslaved people he had killed.

The legal system of 1843 Alabama didn’t recognize those victims as fully human, but it took very seriously any threat to white property owners. As the wagon rolled away, Witmore turned to Samson. The giant stood quietly, his massive frame silhouetted against the cotton field, his expression unreadable.

The plantation owner struggled to find words. “Finally, you saved my life. Webb was about to shoot me.” “Yes, sir.” “Why? I own you. I’ve profited from your labor. You have every reason to let him kill me.” Samson met Whitmore’s eyes for a long moment because your predictable and predictable people can be calculated. “Mr. Web was chaos.”

“Chaos can’t be predicted or controlled. Between the two of you, you were the better mathematics. And besides,” he paused, something that might have been a smile crossing his face. “I need seven more.” “Seven more what?” “Overseers, sir. You said I broke nine men’s spines before turning 25. I’m 22 now. Mr. Rutled was number one. Mr. Web is number two. I have seven more to go in 3 years.”

Whitmore stared, unsure whether Samson was joking or deadly serious. The mathematical precision, seven more, 3 years, 25 years old, suggested careful planning. But the slight smile suggested something else. Perhaps both were true. That night in cabin 7, Samson announced to the darkness “two.” The count continued.

Marcus Webb was hanged three weeks later in front of the courthouse in Mobile, Alabama. His last words were allegedly, “Watch out for the giant.” The warning fell on deaf ears. Whitmore hired a new overseer named Patrick Sullivan, who promised to run a more humane operation. Sullivan lasted 18 months before his own spine broke in a cotton jin accident that was investigated and ruled purely coincidental.

The mathematics of revolution continued their inexurable progression and Samson’s legend began to grow beyond the boundaries of a single plantation. By summer 1846, Samson had turned 25. True to his prediction, nine overseers had suffered catastrophic spine or spine related injuries at Whitmore Plantation or neighboring properties where Samson’s influence had spread. The list read like a medical textbook of vertebral trauma.

James Rutled, shattered knee leading to spinal complications. Marcus Webb, hanged, cervical spine severed. Patrick Sullivan, crushed vertebrae in cotton jin accident. David Morrison, fell from warehouse roof onto lower back. William Hayes, trampled by spooked horses, multiple spinal fractures. Charles Dunore, mysterious paralysis after drinking contaminated water.

Robert Ashford, thrown from wagon, cervical fracture. Joseph Sterling, attacked by wild boar that inexplicably invaded plantation grounds. Michael Prescott simply disappeared one night. His body never found, but his spine embossed journal discovered in woods, suggesting he understood what fate awaited and fled. Each incident was investigated.

Each was ruled accidental or unexplained. In every case, Samson had an airtight alibi. He was in fields surrounded by witnesses picking cotton with mathematical precision. But the pattern was undeniable. Any man who became overseer at Witmore plantation faced a mysterious catastrophic fate. Whitmore found himself unable to hire overseers.

Word had spread through Alabama’s plantation networks. Whitmore’s giant was cursed or blessed or something supernatural. Men refused the position despite generous wages. Those who did accept lasted days or weeks before inventing excuses to leave. The plantation’s management structure collapsed and Witmore was forced to supervise operations personally.

Something unexpected happened as Whitmore struggled to manage without overseers. Productivity increased. Without constant threat of brutal punishment, without psychological warfare and arbitrary cruelty, workers at Whitmore Plantation found themselves operating under a slightly less oppressive system. Whitmore motivated purely by profit rather than moral a whack.

News

“Greg Gutfeld SHOCKS AMERICA WITH A $50 MILLION LAWSUIT AGAINST THE VIEW — ‘THIS WASN’T COMMENTARY… THIS WAS A LIVE-TV ASSASSINATION’”

What began as a typical daytime segment quickly erupted into one of the most controversial media confrontations in recent memory….

The Day the Laughter Stopped: Greg Gutfeld Left Speechless and in Tears After Daughter’s Surprise Studio Visit Following Severe Health Scare

In the high-octane world of cable news and late-night commentary, silence is usually the enemy. Airtime is measured in seconds,…

FOX NEWS SHATTERED: Sandra Smith’s Sudden Rise Sends Shockwaves — Johnny Joey Jones Stunned On Air: “This Changes EVERYTHING.”

A decision no one saw coming has erupted into one of the most explosive media storylines of the year, as…

Jenna Bush Hager shares why she won’t be on TODAY for a while: “a significant shift in the amount of relatives.”

Jenna Bush Hager Reveals the Reason She’ll Be Absent from TODAY in the Coming Days: “A Major Change in the…

“Please Pray for Ollie”: Dylan Dreyer Breaks Down in Tears as She Reveals Son’s “Alarming” Health Battle

In the world of morning television, Dylan Dreyer is known as the “ray of sunshine.” Her infectious laugh, self-deprecating humor,…

Jenna Bush Hager shares her heartbreak over the rare illness her son Hal is facing: “It’s hard to accept he’s battling something so severe.”

Jenna Bush Hager Shares Son Hal’s Funny Habits During Family Trip to Italy Jenna Bush Hager recently opened up about…

End of content

No more pages to load