“I’m a Navy Seal, sweetheart. I’ve forgotten more about combat than you’ll ever learn.”

Commander Jason Milner didn’t say it quietly. He announced it to the entire mixed service training cadre at the Joint Readiness Training Center, Fort Polk, Louisiana, right before his palm connected with Staff Sergeant Raina Kellerman’s shoulder during a close quarters combat demonstration. Not a coaching tap, but a deliberate strike meant to test her balance and embarrass her in front of 35 students from across special operations communities.

She was 31, compact and efficient with hands that moved like they’d solved violent problems in places most people would never see. Milner saw an army NCO who’d gotten an instructor billet through connections rather than capability. He didn’t see the surgical scar on her right shoulder from a fast rope training accident at a facility in North Carolina that didn’t appear on any official maps. He didn’t see the way her eyes tracked movement patterns and threat angles without conscious thought. He saw someone to humiliate, someone whose presence at this level of instruction offended his sense of how the system should work.

What Milner didn’t know was that the woman he’d just struck had spent 3 years as a subject matter expert at a classified training facility, helping develop hand-to-hand combat doctrine that was now being taught to operators across JSOC. The training bay went dead silent. The question wasn’t whether she’d respond. It was what would happen when people found out who she really was.

Fort Polk’s Joint Readiness Training Center sat in the middle of Louisiana Pine Forest, a sprawling complex where conventional and special operations units came to validate combat readiness before deployments. The air smelled like rubber mats and the accumulated sweat of thousands of soldiers who trained here. Staff Sergeant Raina Kellerman, 31, stood near the demonstration area in Army combat uniform with sleeves rolled to regulation standards.

She was 5’6 and maybe 135, built like tensile steel, all functional strength with nothing wasted. Her hair was pulled into a tight bun that met AR670-1 standards, dark brown with a few premature gray strands from deployments in places where stress was measured in hours survived rather than missions completed. Her hands showed the wear of her profession, calloused knuckles, small scars from years of impact training, and the kind of grip strength that came from weapon manipulation and rope work.

She’d been at Fort Polk for 4 months, assigned as a hand-to-hand combat instructor for a joint service advanced tactics course that pulled personnel from across conventional and special operations units. Her orders listed her as a combat instructor with previous assignments in training development. What the orders didn’t specify was where that training development had occurred or who she’d been developing it for.

If you’re watching from Louisiana or any military community tonight, you recognize these training centers where warriors sharpen skills that mean the difference between mission success and failure. If this story hits home, consider subscribing. We cover the operators the system overlooks.

Commander Jason Milner was the senior Navy instructor, a 43-year-old SEAL with 16 years in naval special warfare, and an ego that filled rooms before he entered them. He wore his trident-like armor and carried himself with the confidence of someone who’d spent years being introduced as a Navy Seal before any other qualification.

He’d done solid work. Four deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, competent performance, nothing that would make it into classified after-action reports, but nothing that embarrassed the community either. What ate at him was that he plateaued at O-5, watched younger officers move past him into positions he’d wanted, and spent the last three years teaching rather than operating.

He’d been watching Kellerman since the course started. Didn’t like that she was army teaching techniques to students that included seals. Didn’t like that she carried herself with quiet confidence that suggested she’d proven things he was still trying to prove. Didn’t like most of all the students listened when she spoke and applied her methods without the resistance they showed other instructors.

The scar on her right shoulder hidden under her uniform was from a fast rope training accident 3 years back. She never explained it. The people who knew didn’t ask.

Raina Kellerman grew up at Fort Bragg, now Fort Liberty, in a modest house near the main post that smelled like coffee and boot polish. Her father, Command Sergeant Major Marcus Kellerman, had spent 28 years in the army, most of it with 75th Ranger Regiment and later in advisory roles at the Special Operations Command.

He’d deployed nine times, earned a silver star and three bronze stars with V devices, and carried himself with the kind of quiet professionalism that made subordinates work harder just to meet his standards. He’d retired as the regimental sergeant major and taught his daughter that respect was earned through consistency, competence, and never asking others to do what you wouldn’t do yourself.

Her mother, Rebecca, had been a civilian nurse at Womack Army Medical Center, who’d spent years treating soldiers coming back broken from deployments. She taught Raina that strength came in different forms, that being able to break someone and being able to heal someone both required discipline and precision.

Raina enlisted at 19, chose military police initially because she wanted to prove herself in a combat arms adjacent field, and reclassified to infantry the moment the combat exclusion policy was lifted. She went through Ranger School in 2016 as part of the first group of women to attend after integration. And she’d passed on her first attempt by simply meeting the standard without excuses or accommodations.

Her father attended her graduation and said five words, “You earned it. Keep going.”

What wasn’t in her official service record was the assignment between 2019 and 2022. Someone from the Army’s training and doctrine command had approached her after she’d completed a combatives instructor course at Fort Benning with the highest technical scores in her class. They’d asked if she wanted to help develop training doctrine for specialized units. No details, just an offer that required a security clearance upgrade and an understanding that the work wouldn’t appear in her official record for years.

She’d spent 3 years at a facility near Fort Bragg that was officially listed as a training site, but functionally served as a development center of the special operations tactics. Her job had been to help refine hand-to-hand combat techniques that could be taught efficiently to operators who needed to master multiple skill sets quickly.

She’d worked alongside civilian martial arts experts, former special operations personnel, and soldiers who were testing doctrine before it went into formal training pipelines. The work had been intellectually demanding and physically brutal. Testing techniques under stress, documenting what worked and what failed, training cadres, who would then train operators.

The shoulder injury came during a fast rope training evolution where equipment failure sent her down a 40ft rope faster than intended. She’d instinctively tried to arrest the fall, compounded the shoulder badly enough to require surgical repair, and spent 6 months in physical therapy learning to use her arm properly again.

She’d come back and finish her assignment before rotating to Fort Polk with a service record that showed instructor time, but nothing about where or who she’d trained. Her father had died of a heart attack 8 months after she got to Fort Polk. Suddenly, he’d been running his morning PT, and his heart just stopped. At the funeral, she’d found a letter he’d written years earlier to be delivered after his death.

It said, “The standard is the standard. Gender doesn’t lower it or raise it. You met it. Now help others meet it without excuses.”

She’d carried that letter with her. Read it when the weight of constantly having to prove herself became heavy. I tried to remember that the standard mattered more than the noise around it.

Commander Jason Milner’s fundamental problem wasn’t incompetence. It was that his competence had plateaued years ago, and his ego hadn’t adjusted accordingly. He’d made it through BUD/S on his first attempt, deployed to solid SEAL teams, performed adequately in combat, and spent 15 years being introduced as a Navy Seal at every opportunity.

What haunted him was the realization somewhere around year 12 that he wasn’t going to be legendary, that younger seals were outperforming him, that his name wouldn’t be mentioned in the same breath as the community’s heroes. He’d found his niche as an instructor where his credentials commanded automatic respect and students couldn’t compare him directly to the operators still downrange doing the work he’d aged out of.

And when he’d arrived at Fort Polk to teach close quarters combat to a joint service course, he’d expected to be the unquestioned authority on solving violent problems. Then Staff Sergeant Raina Kellerman had walked into the first instructor planning meeting and Milner’s worldview had started fracturing. She was in the army. She was a woman.

She was a junior enlisted. And she demonstrated techniques during the first week that made his students, including experienced seals and rangers, nod and take notes like they were learning something new. That was when Milner started his campaign. Not overt harassment that would trigger complaints, but subtle undermining that questioned her credibility.

Comments during instructor meetings about how combative doctrine had been watered down to accommodate integration. Questions about her deployment history that she’d deflect with vague references to training assignments, implications that she’d gotten her instructor Billet through diversity initiatives rather than merit.

He’d cultivated relationships with two other instructors, a marine gunnery sergeant named Torres, and an Air Force combat controller, technical sergeant named Klene, who’d laughed at his jokes and played along. The real poison was what he’d said to students between training evolutions. casual comments about how standards had changed, how army combatives didn’t translate to real world maritime operations, how instructor credentials didn’t always reflect actual combat experience.

Students had started watching Kellerman more critically, questioning techniques that worked, second-guessing her experience. Kellerman had noticed she wasn’t blind to the subtle hostility or the way students hesitated before accepting her instruction, but she’d dealt with worse during her time at the classified facility operators who’d initially dismissed her until they’d seen her work.

She’d learned that responding to disrespect just validated it in people’s minds. Better to let the work speak and let skeptics convince themselves. But Milner had mistaken her professional restraint for weakness. had convinced himself that she wasn’t pushing back because she couldn’t. That underneath the calm exterior was someone who knew she didn’t belong at this level.

The demonstration that became the breaking point was scheduled for week 12. Postquarters defensive techniques against larger, more aggressive opponents. Milner was supposed to play the role player while Kellerman demonstrated responses for students to learn and practice standard training evolution they’d done dozens of times with other techniques.

Milner decided to make it a teaching moment about real world violence. He’d spent the morning talking to students about his SEAL training, about combat in Ramadi, about how real fights didn’t follow training room rules. He’d established his credentials thoroughly before the demonstration started. When they squared off on the mats with 35 students watching, SEALs, Rangers, Marine Recon, Air Force Special Operations, Milner announced that she’d probably gotten her position because of her father’s name rather than her own capabilities.

He said it loud enough that every student heard clearly. Then he struck her shoulder with an open palm, not quite a punch, but aggressive enough to force a response to test whether she’d fold under pressure in front of an audience. He expected hesitation, maybe embarrassment. Some visible crack in her composure he could exploit.

What happened instead took approximately 4 seconds and left him flat on his back, staring at ceiling tiles, trying to figure out how he’d gotten there. Kellerman sat alone in the instructor office that night after the training day ended, and students had filtered back to their transient barracks. The room was quiet except for fluorescent lights humming overhead and the distant sound of someone running a buffer across tile floors in the adjacent hallway.

Her shoulder ached where Milner had struck it, not from his hit, but from the old injury, the one that still reminded her of its presence when stress and physical work combined. She could have hurt him badly. That knowledge sat heavy in her chest. She’d chosen the gentlest response in her arsenal, a simple off-balancing technique that had put him on the ground without injury, without lasting damage beyond wounded pride.

She could have applied any of a dozen joint manipulations that would have required medical intervention, could have made him understand viscerally how badly he’d miscalculated. But that wasn’t what her father had taught her. Command Sergeant Major Kellerman had spent 28 years leading Rangers and had always said that professionals chose the minimum effective response.

That violence was a tool requiring precision, not a statement requiring volume. That proving you were dangerous was what insecure people did when they were trying to convince themselves. She pulled out her wallet and found the letter her father had written, the one delivered after his funeral. Read it again, even though she’d memorized it months ago.

“The standard is the standard. Gender doesn’t lower it or raise it. You met it. Now help others meet it without excuses.”

The problem was that she’d spent three years helping develop doctrine at a classified facility, working with some of the best hand-to-hand combat specialists in the military, and none of that appeared in her official record.

To people like Milner, she was just an army staff sergeant with an instructor billet who probably hadn’t earned her position. He had no context for the work she’d done. no understanding that she’d been testing and refining techniques before they went into formal training pipelines that people like him would eventually teach from.

She thought about her father, about the way he’d carried himself confident without being arrogant, competent without needing constant validation, about the letter asking her to help others meet the standard without excuses. Maybe that was the point. not proving herself to people like Milner who’d already decided what they thought, but making sure the students learned what they needed to survive, regardless of who taught them or what assumptions they brought into the training bay.

She closed the wallet and started preparing the next day’s training plan. Students needed to learn how to survive close quarters combat when everything went wrong. That mattered more than Milner’s ego or her own frustration with constantly having to prove she belonged. Colonel William Ashford, the course director, called a mandatory instructor meeting the following morning at 0700.

Ashford was 53 with 29 years of service, most of it in special forces, and he carried himself with the kind of presence that made people pay attention without him raising his voice. He’d been running joint training courses for 8 years and had zero patience for instructors who couldn’t maintain professional standards.

He said that yesterday’s demonstration had been reviewed by multiple observers and that Commander Milner’s conduct had fallen below expectations for senior instructors. He said that aggressive role-playing was acceptable when coordinated in advance, but that striking a fellow instructor without prior agreement and making comments about how she’d gotten her position crossed professional lines.

He said Milner would receive formal counseling and would be restricted to classroom instruction for the remainder of the course. Milner started to protest and began citing his experience and credentials. Ashford cut him off and said that credentials didn’t excuse unprofessional behavior and the part of being a senior operator was knowing when and how to apply pressure appropriately.

Then Ashford said something that caught everyone off guard. He announced that the training cadre would participate in a week-long instructor validation exercise. A compressed evaluation of teaching ability, technical proficiency, and performance under realistic training conditions. All current instructors would participate.

Results would be documented and forwarded to their respective commands for consideration in future assignments. Milner’s face went dark, but he couldn’t object without appearing afraid of evaluation. The validation started the next day. First evolution was teaching effectiveness. Each instructor had to teach a complex technique to students with no prior experience, then have those students demonstrate it against full resistance.

Milner taught a weapon retention sequence that was technically sound, but required too many precise movements to work reliably under stress. Students struggled to execute it against resistance. Kellerman taught a simplified grip break technique that worked even when students made mistakes. Her students executed successfully on first attempts against full resistance.

Second evolution was performance after physical stress. Each instructor completed an 8-mile run with a 35lb rucksack, then immediately demonstrated their primary teaching specialty. Milner finished the run strong, but his technique demonstration afterwards showed fatigue, movements less precise, explanations rushed.

Kellerman finished midpack and demonstrated techniques with the same precision she’d shown fresh, her breathing controlled and movements economical. Third evolution was tactical problem solving under time pressure. A notional hostage scenario requiring immediate action planning with limited intelligence.

Milner’s solution was aggressive, immediate breach, overwhelming force, accepting calculated risks to prevent hostage execution, tactically defensible but high casualty potential. Kellerman’s solution involved establishing containment first, using movement and noise discipline to gather intelligence, then executing precisely when the tactical picture was clarified.

Lower risk, higher probability of success with fewer casualties, the evaluators. Colonel Ashford, a command sergeant major from Ranger Regiment and a Navy Master Chief from Naval Special Warfare, watched without commenting, just took notes. Fourth evolution came on day five, full contact technical demonstration against a resisting opponent in protective gear.

Each instructor faced a student who’d volunteered to provide maximum resistance. Milner went first against a Marine Recon staff sergeant who gave him a solid fight. Milner won, but it took 2 minutes and relied heavily on size and strength rather than technique. Kellerman faced an Army Ranger sergeant first class who was 6’1 and 200 lb.

The engagement lasted 30 seconds. She used his forward pressure against him, executed a hip throw that put him down hard, transitioned to an arm lock that forced an immediate tap. Clean, efficient. Students watching went silent. Final evolution was teaching under adverse conditions. Each instructor had to teach a technique to a deliberately hostile student who questioned every instruction and resisted learning.

Milner became visibly frustrated when his student challenged his methods, eventually just demonstrating the technique himself rather than teaching through the resistance. Kellerman faced a student who openly questioned whether someone her size could teach effective techniques. She responded by having him attack her with maximum effort.

then demonstrated three different controls, then walked him through each technique until he could execute them himself against another student. When the validation ended, Colonel Ashford assembled everyone in the main training bay. Standing beside him was a one-star general nobody had expected. Brigadier General Patricia Hendrix, Deputy Commander of the Army Special Operations Command, who had a reputation for appearing personally when standards or integrity were at stake.

Brigadier General Hendrix was 56 with silver gray hair and a career that included multiple combat deployments with special operations task forces across three decades. She’d come up through military intelligence before crosstraining into special operations support. And she had the kind of credibility that transcended rank and service branches.

She didn’t waste time on formalities. She said she was going to discuss a training initiative that had been classified for operational security reasons, but was now cleared for appropriate professional discussion. She asked if anyone recognized the term “Special Operations Training Doctrine Development Initiative.” Nobody did. Miller looked confused and angry in equal measure.

Hendrix explained that SOTDDI was a three-year program conducted from 2019 to 2022 to develop and refine training doctrine for special operations forces. The program had pulled subject matter experts from across the army to work at a classified facility near Fort Bragg, testing and documenting techniques that would eventually be incorporated into formal training pipelines for JSOC and other special operations units.

The program had focused on developing efficient training methods that could produce consistent results across operators with different backgrounds and physical attributes. She paused, let that settle. Then she said that Staff Sergeant Raina Kellerman had been one of 12 personnel selected for that program.

She’d spent three years helping develop hand-to-hand combat doctrine that was now being taught at every special operations training facility in the army. That her technical expertise had been used to train Cadres, who then trained operators across JSOC, that the techniques students had been learning in this course were based partly on doctrine she’d helped develop.

The training bay went completely silent. Hendrix continued, said that Kellerman’s shoulder injury visible in her medical records had come from a training accident during that assignment. She’d spent 6 months in recovery and rehabilitation, then completed her assignment before rotating to Fort Polk. That her service record showed instructor time, but not the specific details of what she’d been instructing because the program had been classified.

She said the validation exercise just completed had confirmed what multiple evaluators already knew. that Staff Sergeant Kellerman was one of the most technically proficient hand-to-hand combat instructors in the US Army. With expertise developed through years of work at the highest levels of special operations training, Milner’s face had gone white.

Students stared at Kellerman like they were reassessing every assumption they’d made. Gunnery Sergeant Torres looked like he wanted to disappear into the floor. Hendrix turned to Milner and said that credentials mattered, that the seal trident represented genuine accomplishment, but that rank and experience didn’t justify undermining fellow instructors or making assumptions about how someone earned their position.

She said Milner’s conduct would be formally documented and that his command would receive a detailed report. Then she turned to Kellerman and said that based on her performance and her previous service, she was being offered a position as the senior combatives instructor at the special warfare center and school at Fort Liberty.

It meant promotion recommendation to sergeant first class with consideration for master sergeant once time in grade requirements were met and responsibility for training instructors who would teach operators across the entire special operations community. She asked if Kellerman would accept. Kellerman looked at the students.

At Milner, who couldn’t meet her eyes, at Colonel Ashford, who nodded slightly, at the general who’d come to Fort Polk personally to make this offer, she thought about her father, about the letter asking her to help others meet the standard, about whether training instructors who would train warriors qualified as meeting that standard.

She said yes. Hendrix shook her hand and said the orders would be processed within 2 weeks. Then she dismissed the formation, leaving Kellerman standing in the training bay while students approached to shake her hand and apologize for doubts they’d carried. Milner submitted a request for reassignment within 48 hours.

His command approved the transfer to a SEAL team on the West Coast with formal counseling documentation that would remain in his service record. Word spread through Fort Polk faster than official channels. The army instructor Milner had dismissed wasn’t just competent. She was a subject matter expert who developed doctrine at levels most instructors never reached.

Kellerman spent her final two weeks at Fort Polk completing the current course. Every student passed their final evaluation. Several approached her privately to apologize for initial skepticism, and she responded the same way each time, said that skepticism was natural, that what mattered was whether they’d learned what they needed to survive.

On her last morning at Fort Polk, she found an email from Commander Milner. Brief, said he’d been wrong about her and wrong about himself. Said he’d spent years confusing credentials with competence, and that watching her work had forced him to confront that difference. said he was requesting an assignment as a basic training instructor at Great Lakes, where “maybe he could teach new sailors to earn their place rather than assume it.” She read it once, then archived it.

She didn’t need his apology, but she hoped he meant what he’d written. The drive to Fort Liberty took 9 hours through Louisiana and Carolina highways. She reported to the special warfare center in school on a Monday morning that smelled like pine trees and fresh possibilities. The commandant, a command sergeant major named Rivers, who’d spent 26 years in special forces, shook her hand and said he’d read her actual service record, the complete one that included the classified training development work. Said they didn’t get many instructors with her specific background, and that he expected her to maintain the standards that made special operations personnel effective.

Her first class was 12 instructor candidates from across special operations, Rangers, Green Berets, SEALs, Marine Raiders, all senior NCOs with combat experience and strong opinions about methodology.

She stood in front of them wearing her staff sergeant rank and the same scarred hands that had been refining these techniques for years. She introduced herself. Said she’d spent three years helping develop the doctrine they’d be learning to teach. Said she was going to train them to teach others how to survive close quarters combat when everything went wrong.

Said the training would challenge assumptions about what worked and what didn’t. Then she told them to pair up and prepare to work because credentials were just the starting point and what mattered was whether they could teach effectively when lives depended on it. She thought about her father, about the letter, about whether this training teaches counted as helping others meet the standard. It felt right.

News

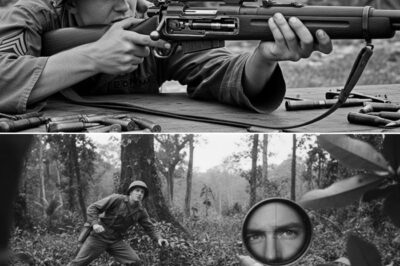

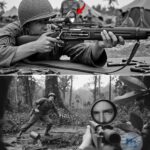

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese…

Overwatch in the Rain: How One Army Sniper Opened a Corridor for a SEAL Team

Rain hammers the tin of a joint task force forward base while generators hum and diesel clings to the air….

Do You Know Who I Am? A Marine Shoved Her at the Bar — Not Knowing She Commanded the Navy SEALs

“Women like you get good men killed out here.” The words slammed into Commander Thalia Renwit like a fist as…

Captain Poured Coke on Her Head as a Joke — Not Knowing She Was the Admiral

“You look like you could use a shower, sweetheart.” Captain Derek Holland thought it was funny when he dumped the…

I Can’t Close My Legs,” Little Girl Told Bikers — What Happened Next Made the Whole Town Go Silent

From the very first moment, something felt wrong in that quiet motorcycle workshop on the edge of a forgotten American…

Kind Old Lady Shelters 15 Bikers in a Snowstorm — Next Morning, 100 Bikes Lined Up Outside Her Home

The snow fell heavy that night, swallowing the small town in silence, blanketing the world in a white so thick…

End of content

No more pages to load