If you were a betting man in the summer of 1941, you wouldn’t have put a dime on the survival of the Soviet Union, let alone the survival of a 24 year old history student named Ludmila Pavlichenko. At that time, the prevailing wisdom in Moscow, Berlin, and arguably even Washington was that warfare was a biological impossibility for women.

The general consensus held that the female constitution was simply too fragile for the butchery of the infantry. Women belonged in the field hospitals, scrubbing floors and bandaging wounds shielded from the ballistic reality of the front line. But history has a way of shattering our assumptions when survival is on the line.

When Ludmila walked into a recruiting office in Kiev, the officer took one look at her manicured nails and university transcripts and laughed. He told her to “be a nurse,” he told her. “Combat was about blood, screams and death, things a woman supposedly couldn’t handle.” Ludmila didn’t argue with emotions. She argued with ballistics.

She told him she had been shooting since she was 14, clocking top tier scores in regional marksmanship clubs. When the officer smirked, she demanded a test. He pointed to a fence post 100m downrange. Ludmila raised a rifle and put five rounds through the center of the post. The officer stopped laughing.

He stopped laughing because he was looking at an anomaly that shouldn’t exist. A woman who treated a rifle not as a heavy foreign object, but as an extension of her will. However, marksmanship on a range is calm. Marksmanship. In 1941, Ukraine was chaos. By August 8th, the axis forces had tightened the noose around the port city of Odessa.

The Romanian Fourth Army, supported by their Wehrmacht elements, had sent a massive force swelling to nearly 160,000 men to crush the city. The Soviets were outnumbered significantly. The Red Army was losing men faster than they could draft them, which is the only reason Ludmila found herself in the 25th Rifle Division, lying in the dirt behind a stack of rubble in the village of Belyayevka.

She had been on the line for six hours without food or sleep, she had a standard issue Mosin Nagant bolt action rifle, 40 rounds of ammunition and a very personal score to settle. Just 11 days earlier, the Luftwaffe had bombed Kiev University. Her mentor, Professor Anatoly Vulov, had been buried alive under the masonry for two hours before they pulled his body out. Her best friend Natasha had been trapped in the library when the incendiaries hit.

The fire consumed the building before she could get out. Ludmila wasn’t there for glory. She was there because her world had been incinerated. At 547, in the morning, the theory of gender roles collided with the reality of the Eastern Front through a crack in a farmhouse wall 280m away. Ludmila spotted a German helmet.

The enemy sniper was tracking a Soviet sergeant named Dmitry Kravchenko, a man who just the day before had shared his bread ration with Ludmila. Kravchenko had no idea he was seconds away from death. In that moment, Ludmila didn’t panic. She didn’t faint. She remembered her instructor’s voice echoing in her head: “Don’t think about killing. Think about solving a problem.” It was a ballistic equation. Distance 280m.

Wind a light cross breeze from the west. Target. Stationary. It ceased to be murder and became mathematics. She adjusted for windage, settled the crosshairs and squeeze the trigger. The rifle kicked against her shoulder. The sound cracking across the valley through the scope. The German helmet jerked backward and disappeared.

One shot, one kill. She felt no guilt. No satisfaction. Just a cold, mechanical curiosity about where the next target was hiding. This wasn’t the behavior of the weaker sex. It was the birth of the deadliest female sniper in history who had just cleared the first variable in an equation that would eventually equal 309.

To understand why Ludmila Pavlichenko had to reinvent the art of sniping, we first have to understand the meat grinder that was the siege of Odessa. By late August 1941. The situation wasn’t just desperate. It was terminal. The Wehrmacht had the city in a chokehold, cutting off water supplies and pounding the defensive lines with the level of artillery precision that the Soviets simply couldn’t match.

In this environment, order is supposed to be the antidote to chaos. When bullets are flying and command structures are fracturing. Soldiers cling to their training. They cling to the book. For Soviet snipers, that book was the official infantry doctrine of the Red Army. It was a rigid set of rules designed to keep valuable specialists alive. The logic seemed sound.

“Never fire more than three shots from one position. Never stay in a hide for more than 30 minutes. Always have a primary, secondary and tertiary firing position and crucially, always move immediately after an engagement.” It sounds sensible, doesn’t it? It’s the military equivalent of hit and run. But there was a catastrophic flaw in this logic that nobody in Moscow had accounted for.

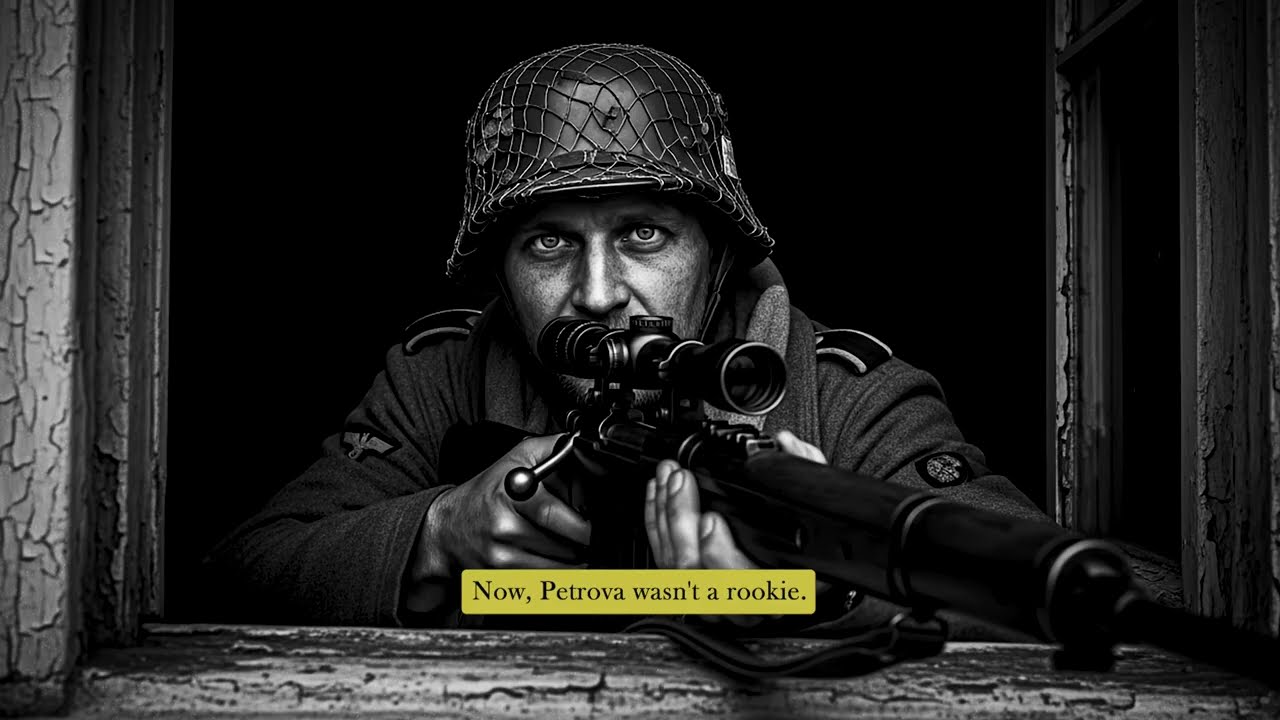

The Germans had read the same book. The first tragic proof of this failure arrived on August 19th in the form of Lieutenant Tanya Petrova. Now, Petrova wasn’t a rookie. She was a hardened specialist with eight months on the line and 47 confirmed kills. She was smart, disciplined and by all accounts, a model soldier. She did exactly what she was trained to do.

She positioned herself on the third floor of a bombed out apartment building. Textbook elevation. She engaged a German machine gun crew at 320m, a single efficient hit. Perfect execution. Following the doctrine, she immediately packed up and moved to her pre-planned secondary position on the second floor.

She waited 20 minutes, again following the rules to let the heat die down, and then engaged a German officer. Another clean kill. Here is where the book betrayed her. The doctrine dictated that she must now rotate to her tertiary position on the ground floor to avoid triangulation. It was a predictable linear regression. Top. Middle. Bottom. Waiting for her was Hans Becker. Becker wasn’t just a German soldier.

He was a counter sniper specialist with 89 confirmed kills. He understood Soviet bureaucracy better than the Soviets did. He knew that a disciplined Russian sniper would never fire from the same floor twice. So after seeing the muzzle flash on the third floor and then the second, he didn’t bother scanning those windows.

He simply aimed his Mauser at the stairwell window leading to the ground floor. And waited. He was hunting an algorithm, not a person. One more observer passed that window, executing her doctrinal movement. Becker put a single bullet through her chest. Ludmila was one floor below. She heard the shot. She heard the body fall. And most chilling of all, she heard the Germans across the street laughing.

They didn’t just kill her friend. They outsmarted the entire Soviet military academy. Therefore, the lesson should have been learned. But military institutions are slow, lumbering beasts. They don’t pivot on a dime, even when the cost is blood. Just eight days later, the doctrine claimed another victim. Corporal Victor Stepanov was the opposite of Petrova.

He was 19 years old, fresh faced with only six weeks of experience. But he was eager to please, and he followed his orders to the letter. On August 27th, he set up in a drainage ditch 400m from the German lines. It was a textbook position, excellent concealment, narrow sightlines, good cover.

Stepanov engaged a patrol at dawn, dropping two Germans. The survivors scattered. Now the instinct of survival says run. But the doctrine said, “stay low, wait 15 minutes, then move to the secondary position.” The logic was to ensure you weren’t spotted while moving. So the 19 year old kid stayed in the ditch. He checked his watch. He waited. The problem was that the Germans had changed the game.

They weren’t just using snipers to hunt snipers anymore. They were using mathematics and heavy ordnance. German spotters had seen the general direction of Stepanov shots. They didn’t need to see his head. They just needed to know which grid square he was in. They knew Soviet doctrine mandated a waiting period. They knew he was still there. They didn’t send a sniper.

They called in an artillery strike. A high explosive shell landed directly in the drainage ditch. It was an obliteration. Kill. There was nothing left of Viktor Stepanov to bury. He had died because he did exactly what he was told by September. Ludmila Pavlichenko had watched seven of her fellow snipers die. Every single one of them was a disciplined soldier.

Every single one followed the rules of engagement. And every single one returned to base in a body bag or didn’t return at all. This creates a terrifying psychological crisis for a soldier. Usually you believe that if you are skilled and disciplined, you will survive. But Ludmila realized that on the Eastern Front, discipline was a death sentence.

The German counter sniper units were simply too good. They had analyzed the Soviet pattern of operations, the defensive posture, the waiting, the reactive shooting. And they had built a machine to dismantle it. The Soviet snipers were fighting like prey, hiding, waiting for an opportunity and trying to escape.

The Germans, especially veterans like Hans Becker, were fighting like predators, active, aggressive and manipulative. They forced the Soviets to move and then punish that movement. Ludmila sat in her dugout, cleaning the Cosmoline off her Mosin Nagant and came to a radical conclusion. The problem wasn’t marksmanship. The Soviets could shoot just as straight as the Germans. The problem was the philosophy.

To survive Odessa, she had to stop acting like a soldier following orders and start acting like a hunter. Setting a trap, she had to throw the rulebook into the fire, because following the rules was the quickest way to join Petrova and Stepanov in the grave. In any rigid hierarchy, whether it’s a corporate boardroom or the Red Army, doing something illegal is usually the fastest way to lose your job. Or in 1941, Soviet Russia, your life.

But Ludmila Pavlichenko reached a breaking point. She realized that the Soviet sniper doctrine was essentially a defensive manual. It taught soldiers how to hide and how to wait. It was passive. However, warfare is not a passive activity. It is an imposition of will. Ludmila realized that to survive against the superior force, like the Wehrmacht, she had to stop thinking like a soldier protecting a position and start thinking like a hunter baiting a trap.

She decided to do the one thing the manual explicitly forbade. She was going to expose her position on purpose. This was the birth of the dual nest strategy, a tactic so reckless that her commanding officers would have likely court martialed her on the spot. Had they known the details. Desperation, however, is the mother of invention.

The concept was terrifyingly simple. Instead of finding one perfect hiding spot, Ludmila would dig two. The primary nest was the bait. Here, she would position a decoy, a helmet propped on a stick, or a spare tunic stuffed with straw and leaves to mimic the silhouette of a prone soldier. It didn’t have to be perfect.

It just had to be convincing. From 300m away, through the distorted glass of a German scope. The secondary nest was the kill zone. This was an expertly concealed hide located only 4 to 6m away. Close enough to traverse in seconds, but far enough to be outside the immediate blast radius. If the Germans used explosive rounds, here was the gamble.

She would wait in the secondary nest, essentially watching her own ghost. When a German sniper took the bait and fired at the helmet in the primary nest. Two things would happen instantly. First, the German would reveal his position through the muzzle flash. Second, he would rack the bolt of his Mauser, watching through his scope to confirm the kill.

He would see the helmet jerk or the straw man slump for a human brain processing visual data. It takes about 2 to 4 seconds to realize that the body isn’t bleeding or falling naturally. Those 2 to 4 seconds were the difference between life and death. That was Ludmila’s window. While the German was cognitively processing the deception.

Ludmila would already have his chest in her crosshairs. She tested the suicidal theory on September 3rd, 1941. The setting was a ruined cellar near the front line. The German lines were 340m away, a comfortable distance for a marksman, but close enough for mistakes to be fatal.

Ludmila set up her mannequin in the primary nest, propped up on debris, as if observing the field. Then she slid into the darkness of her secondary position. Five meters to the right. And then began the hardest part of sniping the waiting. Movies make sniping look like constant action. In reality, it is an endurance sport of pain management. Ludmila lay motionless for 45 minutes.

Her muscles cramped, her vision blurred from the strain of staring through the scope. Insects crawled across her hands and face, and she couldn’t twitch a muscle to swap them away. To move was to die. At 6:17 a.m., the silence broke. A shot cracked across no man’s land. In the primary nest, the decoy helmet spun violently backward.

The German had taken the bait. Ludmila didn’t flinch. She scanned the German line there 320m out, a wisp of smoke and a figure shifting behind a brick wall. The German was adjusting his bolt, waiting to see his target fall. He was confident. He was secure, and he was dead. Ludmila had roughly three seconds. She didn’t overthink the windage. She acquired the shape, exhaled and squeezed.

The figure dropped instantly. But here is where the genius of her adaptation kicked in. A rookie would have cheered. A doctrinal soldier would have stayed to confirm. Ludmila did neither. She immediately abandoned both positions and sprinted 40m west to a tertiary building. Only then did she raise her scope to check her work.

She saw two German soldiers dragging a body away from the brick wall. The experiment was a success. Over the next six weeks, she refined this bait technique into a science. She began to profile her enemy with the obsession of a serial killer. She noticed that German snipers were creatures of habit.

They preferred elevated positions, second or third floor windows because it gave them a commanding view of the battlefield. They like to keep the sun at their backs, to avoid glare in their optics, and fatally. They rarely changed positions during the day because they felt safe in their superiority. Ludmila inverted all of this.

She built her kill nest at ground level, where the Germans rarely looked because it offered poor visibility. She timed her hunts for the hours when the sun would be blinding the Germans, using the glare as natural camouflage. It was a high stakes game of chess, where she forced the opponent to play with the sun in his eyes. By October, she had 78 confirmed kills. 22 of them were enemy snipers.

Word spread. The infantry, usually suspicious of the loners with scopes, began to view her as a guardian angel. Officers who were losing men daily came to her begging for help. They brought vodka, extra rations, and sometimes just their grief. On October 12th, the lieutenant named Volkov approached her. He was desperate.

His platoon near a railway junction was being dismantled by a single German sniper. This enemy was a shadow. He had killed nine men in four days. Officers, radio operators, machine gunners. He was picking off the high value assets and vanishing. Volkov. Men were paralyzed. They refused to move. The German wasn’t just killing bodies. He was killing the unit’s will to fight.

Ludmila took the job. Not for the vodka, but because she remembered the seven friends she had already buried. She spent two days just watching the railway junction from 800m away. She mapped the terrain. She counted the buildings. She noted the wind patterns swirling through the steel skeletons of the train cars.

She identified 11 possible hiding spots for the German. 11 was too many to watch. If she guessed wrong, Volkov would lose another man or she would lose her life. She had to force a choice. She set up her trap five meters from where the Soviet soldiers congregated. She constructed a high quality decoy dressed as a Soviet officer, the irresistible target.

She positioned it so it was visible from eight of the 11 potential German hides. Then she hid 12m away and waited. At 6:30 a.m., the decoy officer appeared. Minutes ticked by. Ten, 20. 30. 40 minutes of agonizing stillness. At 7:11 a.m., the shot came. The decoys had snapped back. Ludmila saw the muzzle flash instantly.

It came from a destroyed boxcar 420m down the track. This was a revelation. Ludmila had considered the boxcar, but dismissed it. Why? Because a boxcar is a thin metal trap. If Soviet artillery spotted a sniper there, a single high explosive shell would turn it into a shrapnel grenade. No sane sniper would hide there. But this German was smart.

He had calculated that the Soviets were short on ammunition, and wouldn’t waste a precious artillery shell on a single wrecked train car. He bet his life on Soviet logistics, and he had been winning until now. Through the open door of the boxcar. Ludmila saw the German moving. He was cycling as bolt, probably grinning at another officer kill. He had about five seconds of satisfaction left.

Ludmila fired through the scope. She saw him stumble. It wasn’t a clean kill. He was wounded, scrambling to escape the metal trap he’d built for himself. She chambered another round. The bolt action was smooth, familiar. She fired again. The German dropped and didn’t move. When Volkov s men swept the boxcar later, they found him dead with two holes in him.

One in the shoulder, one in the head. His logbook claimed 67 kills. He was a master of his craft, but he had made the mistake of engaging a woman who understood that the only way to win a fair fight is to make sure it isn’t fair. She told Volkov it was “simple mathematics,” but we know better. It was the calculated application of courage.

She turned herself into the worm on the hook to catch the fish. And speaking of location, whether you’re watching this from a high rise in Chicago, a farmhouse in the UK, or anywhere in between, we want to know where our history keeping community is located. Drop your city or state in the comments below.

It’s amazing to see how far these stories travel. If Odessa was a tragedy, Sevastopol was an apocalypse. By November 1941. The German war machine had pushed the Soviet defenders to the very edge of the Crimean peninsula. The Siege of Sevastopol wasn’t just a battle, it was a cage match where the cage was shrinking every day.

Food was scarce, ammunition was rationed, and hope was the rarest commodity of all. But amidst the shelling and the starvation, a new threat emerged that terrified the Soviet command more than the Luftwaffe bombers overhead. A single German sniper had arrived in the sector. This wasn’t an ordinary marksman. In three days, he had eliminated 11 Soviet soldiers. But it wasn’t the number that was chilling.

It was the selection. He wasn’t shooting random infantrymen. He was killing officers, sergeants and radio operators. He was systematically decapitating the Soviet command structure. The effect was devastating. When you kill the men who give the orders, the unit paralysis spreads like a virus. Officers stopped wearing their rank insignia. Sergeants refused to stand up to shout commands.

The defense of the sector was beginning to disintegrate from the top down. Major Chernov called Ludmila to his bunker. The mood was grim. He laid out the photographs of the victims. Every single one was a single shot to the head or chest. No wounded, no follow up shots needed. This was the work of a virtuoso.

Chernov gave Lyudmila a simple, brutal ultimatum. “Find him and kill him. You have 48 hours.” If she failed, the sector would likely collapse. The Germans would break the line and thousands of Soviet troops would be encircled. It was a duel for the soul of the city. Ludmila accepted. This was the moment she had been training for since she first picked up a rifle at 14.

But she didn’t rush out to the front line with her gun blazing. That’s how you die. Instead, she went to work like a detective. She analyzed the kill zones. All 11 deaths had occurred within a 400 meter radius of a specific ruin complex. They all happened in the early morning between 545 and 730. This told her the German was a creature of routine, but a smart one.

When she plotted the angles of the shots on her map, she realized he never fired from the same position twice. Monday, he shot from the northeast. Tuesday the southwest. Wednesday the northwest. He was walking around the perimeter, constantly shifting his hide to keep the Soviets guessing. This German was a mirror image of everything Ludmila had been fighting against.

He was disciplined. He was mobile. He was following the doctrine of shoot and move to perfection. He was, in essence, the perfect soldier. To catch him, Ludmila needed help. She recruited Lieutenant Boris, a reconnaissance officer who knew the ruins of Sevastopol like the back of his hand. Together, they crawled through the rubble at night.

Mapping the terrain from the perspective of a predator. They were looking for line of sight. The German had to see his targets to kill them. This meant he needed elevation and clear lanes of fire. Ludmila identified 14 buildings that offered the necessary vantage points. 14 was too many. She had to narrow the field. She lay in her bunk that night, staring at the ceiling, running the variables.

Why? Early morning? Why that specific time window? Then it clicked. 600 hours to 700 hours was shift change. The night sentries were tired and swapping out with the morning crew officers were moving between bunkers for briefings. The light was low and tricky.

The German was hunting during the moment of maximum confusion and vulnerability. Using this insight, she eliminated the positions that had poor visibility at dawn. She was left with three high probability locations the north tower of a bombed out church, the third floor of a collapsed apartment block, and the rooftop of a former schoolhouse. Now she had a location, but she still needed a trigger. On the morning of November 8th.

Ludmila Pavlichenko made the most dangerous decision of her life. She decided that a dummy on a stick wouldn’t fool a sniper of this caliber. He was too good. He would spot the fake. So she decided to be the bait herself. At 5:42 a.m., Ludmila crawled into position near the Soviet command post. She was wearing an officer’s greatcoat she had borrowed from a corpse.

It was too big. But from 300m, the silhouette was unmistakable. She stood up. Let that sink in. In a sector terrorized by a sniper who never missed. She stood up in the open. She propped her rifle behind a pile of rubble four meters away. If the German took the shot, she calculated, she would have roughly 1.5 seconds to react.

If she was wrong about his location, she would be dead before her body hit the ground. If she was right, she would have one chance to dive, grab her rifle and fire before he disappeared. She stood there for 17 minutes. 17 minutes is an eternity when you are waiting to be shot. The wind cut through the oversize coat.

Her instincts were screaming at her to dive for cover every distant crack of a rifle made her heart hammer against her ribs. But she stood still. Hands relaxed, mimicking the posture of a bored officer waiting for a briefing. 5:59 a.m. the crack of a Mauser K 98 is distinct, sharp, flat, authoritative. Ludmila heard the sound an instant before she felt the air displace around her head. The bullet snapped past her ear, parting her hair.

He had missed by centimeters. She didn’t freeze. She didn’t panic. She dove not backward into safety, but sideways toward her rifle. She hit the ground hard, ignoring the bruising impact. Her hands found the Mosin Nagant instantly. It was muscle memory. She swung the barrel toward her primary suspect. The church tower. Through the scope, the world narrowed to a circle of glass.

There, 300m away, the third floor of the bell tower. A shadow was moving back from the opening. The German had taken the shot he had missed. And now, following his doctrine, he was retreating into the shadows to relocate. Ludmila had three seconds before he vanished into the darkness of the stairwell. She didn’t check the wind. She didn’t calculate the drop.

There was no time for mathematics. She trusted her hands. She trusted the thousands of rounds she had fired since she was 14. She centered the crosshair on the retreating shadow and fired. It was an instinct shot. The kind marksman instructors tell you never to take because it’s reckless. But combat is reckless. The rifle kicked through the scope. She saw the shadow jerked violently.

The figure staggered and then fell backward, out of sight. Silence returned to Sevastopol. Ludmila didn’t move. Was he dead or was he wounded and waiting for her to pop her head up to check? She chambered another round and held her arm on the tower window. Three minutes passed. Nothing. Ten minutes. The sun began to rise, properly illuminating the dust motes dancing in the air.

15 minutes. Finally, she signaled Lieutenant Boris and his clearing team. They advanced on the church, moving expertly from cover to cover. Rifles raised. Expecting an ambush. Ludmila watched over them. Her finger hovering on the trigger, ready to put a bullet in anything that moved in that tower. They breached the building. Minutes ticked by.

Then Boris appeared in the tower window. He waved target down. Confirmed kill. When Ludmila lowered her rifle, her hands were shaking. It wasn’t fear. It was the adrenaline crash. She had just won a duel against the Phantom. When the Soviet soldiers inspected the body, they found a story in the details.

The German sniper had taken a single round through the chest. He was dead before he hit the floor in his hands. He was still clutching his rifle. A Mauser K 98 with a custom high power optic. This wasn’t a standard infantry issue. This was a hunter’s weapon. But the real revelation was in his pocket. They found a logbook. It was a meticulous record of death. Names. Dates. Ranges. Wind conditions.

The logbook revealed that this wasn’t just a soldier. He was a highly decorated ace who had been deployed specifically to hunt in the Crimea. Historians have debated the exact identity of this German sniper for decades. In her memoirs, Pavlichenko described finding a logbook claiming hundreds of kills, marking him as one of the deadliest opponents on the Eastern Front.

Whether he was a singular super sniper or a composite of the lethal specialists, the Germans deployed. The reality remains he was a master of his craft. But here, here’s the truth. It doesn’t matter whether his name was König, Thorvald, or simply Hans. The fact remains a highly skilled German sniper paralyzed a critical sector of the Sevastopol defense. He killed 11 men in three days.

He was dismantling the Soviet command. And Ludmila Pavlichenko, a 25 year old history student. I’d thought him out, weighted him and ultimately outshot him. She didn’t win because she had a better rifle. She won because she was willing to break the rules of survival. She won because she realized that to kill a monster, you have to be willing to offer yourself as the meal. This victory at Sevastopol cemented her legend. But the war wasn’t over.

Lyudmila would go on to fight for another seven months. However, the physical toll of her bait tactics was mounting. She was wounded four times. In September 1941. Mortar shrapnel tore into her arm and shoulder. She bandaged it in the field and was shooting again the next day. In December, an artillery shell landed ten meters from her position.

The concussion knocked her unconscious for two minutes. She woke up, shook off the dizziness, and refused evacuation. In February 1942, she was caught in an airburst barrage from a German 88 flak gun. Shrapnel shredded her calf. She was immobile for a week, but dragged herself back to the line after ten days. But in June 1942, her luck finally ran out.

During a massive mortar bombardment, she was caught in a shallow trench around landed close to close. Shrapnel slammed into her face. It cut her cheek open, damaged her eye socket and fractured her jaw. She was blinded by blood. The medics who found her thought she would die from shock. She survived. Of course she was, Ludmila.

But as she lay in the hospital in Sevastopol recovering from surgery that saved her eye but scarred her face forever. The Soviet high command made a decision that would change her life more than any bullet. She was now too famous to die. With 309 confirmed kills. She was a living symbol of Soviet resistance. If the Germans killed her now, it would be a crushing propaganda blow. So Josef Stalin himself signed the order.

Ludmila Pavlichenko was to be pulled from the line immediately. She was 25. She had served for 11 months. She had killed 309 fascists. And now she was being told her war was over. She begged to stay. She told them she could still shoot. She told them her friends were still dying. But orders were orders.

Lady death was going on tour, and her next battlefield wouldn’t be a ruined city in Ukraine. It would be the polished floors of the white House. It is hard for us today to imagine the sheer cultural vertigo. Ludmila Pavlichenko must have felt in the autumn of 1942. One month she was eating canned meat in a muddy trench in Sevastopol, smelling cordite and death.

The next she was sitting in the white House drinking tea with Eleanor Roosevelt. The Soviet high command had sent her on a goodwill tour to the United States. The mission was political to convince the allies specifically the Americans, to open a second front in Europe to relieve the pressure on the Red Army to the Soviets. Ludmila was a hero to the Americans. She was a curiosity.

When she stepped off the train in Washington, DC, she didn’t look like a diplomat. She wore her standard issue Red Army uniform olive drab, functional and ill fitting. She wore no makeup. Her face still bore the fresh, angry scar from the mortar shrapnel in June. The American press didn’t know how to handle her. In 1942, America. Women were vital to the war effort. Yes.

But as Rosie the Riveter building planes and factories or as nurses, the idea of a woman lying in the mud for three days to put a bullet through a man’s brain was alien. It was terrifying. The reporters descended on her like vultures. But they didn’t ask about her tactics. They didn’t ask about the ballistics of the Mosin Nagant or the strategic situation in Crimea.

One reporter from the Washington Post asked her if she wore makeup at the front. Another asked if she curled her hair before a battle. A third commented that her uniform made her look fat and asked why she didn’t wear something more feminine, perhaps a shorter skirt. Ludmila, who had watched her friends blown to pieces by artillery, stared at them in disbelief.

She answered with a quote that should be etched in stone. “Gentlemen, I am 25 years old and I have killed 309 fascists invaders by now. Don’t you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?” It was a slap in the face to the American ego. But one person in that room wasn’t offended. She was captivated.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady of the United States, saw something in Ludmila that the press missed. She saw a kindred spirit, a woman operating in a man’s world, refusing to apologize for her competence. In a move that shocked the State Department, Eleanor invited Ludmila to stay at the white House not for a formal dinner, but as a houseguest.

For weeks, the deadly Soviet sniper and the aristocratic American First Lady lived under the same roof. They were an odd couple. Eleanor was tall, patrician, and diplomatic. Lyudmila was short, blunt, and scarred by war, but they formed a genuine friendship. Eleanor took Ludmila under her wing, teaching her how to navigate the shark tank of American politics, while Ludmila told Eleanor the unvarnished truth about the war in the East. This friendship transformed the tour.

Eleanor arranged for Ludmila to speak at rallies across the country New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and as Ludmila traveled. Something shifted. The American public began to see past the uniform in Chicago. Thousands of people packed the stadium to hear her speak. Ludmila stood at the podium, looking out at a sea of well-fed, safe Americans. She didn’t deliver a prepared propaganda speech.

She spoke from the gut. She told them about the burning of Kiev University. She told them about her friend Natasha. She told them about the baby killers of the Wehrmacht. The crowd went silent. Then they erupted. Men took off their hats. Women wept.

For the first time, the reality of the Eastern Front became tangible to the American heartland. It wasn’t just lines on a map. It was this young woman with the sad eyes and the scar on her cheek. American magazines began to change their tune. They stopped calling the girl sniper and started calling her the most dangerous woman in the world. Woody Guthrie, the legendary folk singer, even wrote a song about her. “Miss Pavlichenko was well known to fame. Your country fighting is your game.”

However, the military establishment was harder to win over. American officers were deeply skeptical of her 309 number. To them, it seemed statistically impossible. A kill rate that high in just 11 months. It sounded like Soviet propaganda. So the U.S. War Department quietly conducted its own investigation.

They didn’t just take her word for it. They used their intelligence networks to cross-reference her claims with captured German casualty reports and radio intercepts from the Sevastopol sector. What they found silenced the doubters. The dates matched the locations matched the spikes in German. Officer casualties coincided perfectly with Ludmila’s presence in those specific sectors.

The Germans themselves had corroborated her story in their own panicked radio transmissions about the “Russian witch” she wasn’t lying. If anything, the number 309 was conservative, as it only counted kills confirmed by a third party witness. The real number was likely much higher. By the time the tour ended in early 1943, Ludmila was exhausted.

She had shaken thousands of hands, smiled for endless photos, and answered the same inane questions about lipstick 100 times. She had become a symbol, a caricature. She hated it. She told Eleanor that she felt more tired standing on a stage in New York than she ever felt, lying in an ambush in Odessa. In combat, she had agency.

She had a rifle. She could solve the problem. In America, she was just a prop. But the mission was a success, and her tour helped shift American public opinion. It humanized the Soviet ally. It helped pave the way for the eventual opening of the Second Front. D-Day. In 1944, when Ludmila prepared to leave for Moscow in 1943, she gave Eleanor Roosevelt a gift. A traditional Russian shawl.

It was a small personal gesture between two women who had reshaped history in their own ways. They promised to write and remarkably, they did. Even as the Cold War descended and the Iron Curtain fell, turning their nations into bitter enemies, the sniper and the First Lady kept in touch. Ludmila returned to a Soviet Union that was very different from the one she left. The tide of war had turned at Stalingrad.

The Red Army was marching west. But for Ludmila, the war was over. She was too valuable to risk. She would never fire a shot in anger again. Instead, she was given a new mission, one that would ensure her legacy lived far longer than her own life. She was sent to the sniper schools. It was time to teach.

When the guns finally fell silent in 1945, the world celebrated. Parades marched down Fifth Avenue and Red square. Generals were given medals. Politicians gave speeches. But for the soldiers who had lived in the dirt and the blood, the silence was deafening. Ludmila Pavlichenko returned to Kiev, the city where her war had begun. She didn’t return to the front line, but she had spent the last two years of the war doing something perhaps even more important.

Cloning herself as a chief instructor at the Soviet Vystrel sniper school, she had trained hundreds of young marksmen. She taught them everything she knew. She taught them that patience was a weapon. She taught them that the sun was an ally. And most importantly, she taught them the bait technique. Her students took these lessons to Stalingrad, to Kursk and all the way to Berlin.

Vasily Zaitsev, if the hero of Stalingrad, who killed 225 Germans, used tactics that were direct descendants of Ludmila’s innovations, by 1944, the entire Soviet sniper doctrine had shifted from defensive to aggressive, largely due to her influence. She had changed the DNA of the Red Army. But when the war ended, Ludmila did something extraordinary for a hero of the Soviet Union.

She simply stopped. She didn’t become a politician. She didn’t write a self-aggrandizing memoir to cash in on her fame. She went back to school. She finished the history degree that the war had interrupted in 1941. It was a poetic closure. The history student who had been forced to make history, finally returning to study it. She worked as a historian for the Soviet Navy.

She married. She had a son. She lived a quiet, modest life in a small apartment in Kiev. To her neighbors, she wasn’t Lady Death. She was just Ludmila. The woman who looked tired and sometimes rubbed a scarred cheek when the weather turned cold. But the war never really left her. In rare interviews, she admitted that the faces of the men she killed still visited her.

She said “every German who remains alive will kill women, children and old folks dead. Germans are harmless. Therefore, if I kill a German, I am saving lives.” It was a rationalization, a mantra to keep the ghosts at bay. But those who knew her said her eyes never lost that thousand yard stare.

The look of someone who has seen the absolute worst of humanity and survived it. In 1957, 15 years after their meeting. Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Soviet Union. The Cold War was in deep freeze. The KGB monitored her every move. But Eleanor insisted on seeing her old friend. She went to Ludmila’s apartment in Kiev. The Soviet handlers were nervous. They wanted a controlled meeting.

But when Ludmila opened the door and saw the former first Lady protocol collapsed. The two women embraced Ludmila. The iron sniper wept on Eleanor’s shoulder. For a few hours, the Cold War didn’t exist. Just two friends catching up in a small kitchen. Ludmila Pavlichenko died on October 10th, 1974. She was only 58 years old.

The official cause was a stroke, but many believe it was the long term toll of her injuries and the invisible weight of PTSD. She was buried with full military honors in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. But as the decades passed, her name began to fade. The West forgot her because she was a Soviet. The Soviets forgot the nuances of her story because they preferred the simple propaganda version.

Today, however, her legacy is everywhere. Even if we don’t see her name. When a U.S. Marine Scout sniper sets a trap in training, he is using a variation of her bait technique. When a historian writes about the role of women in combat, her name is the first citation. She proved that a warrior isn’t defined by gender, but by the will to endure.

She proved that sometimes you have to break the rules to save your people. And she proved that a 24 year old history student could stare down the Wehrmacht through a four power scope and make them blink first. Ludmila Pavlichenko was the woman who never missed.

And it is our job to ensure that history never misses her.

News

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese…

He Died in a Fire in 1980 — 12 Years Later, His Mother Sees Him Alive on a TV Broadcast…

The morning of April 12, 1980, dawned like any other in Toledo. Teresa Munoz woke up at 7, prepared breakfast,…

What Happened After 16 Generations of “Pure Blood” Tradition Created a Child No One Could Explain

There’s a photograph that still exists locked in a vault in Virginia. It shows a child who should not have…

They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese…

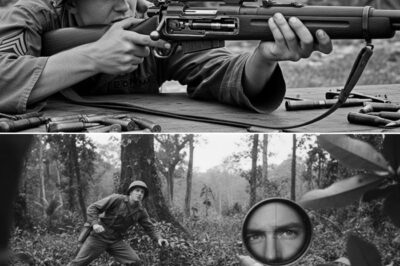

Overwatch in the Rain: How One Army Sniper Opened a Corridor for a SEAL Team

Rain hammers the tin of a joint task force forward base while generators hum and diesel clings to the air….

Do You Know Who I Am? A Marine Shoved Her at the Bar — Not Knowing She Commanded the Navy SEALs

“Women like you get good men killed out here.” The words slammed into Commander Thalia Renwit like a fist as…

End of content

No more pages to load