In the dead of a Belgian winter on December the 17th, 1944, the most powerful armored weapon of the Second World War ground to a halt. The Tiger 2 tank, a 70-ton beast of steel and firepower, sat silent in the pre-dawn gloom. Its commander, the decorated SS Colonel Joachim Peiper, slammed a fist against the cold turret.

The engine had coughed, sputtered, and died. All around him, stretching back for miles into the misty Ardennes forest, his entire battle group, Kampfgruppe Peiper, was paralyzed. 67 tanks, hundreds of armored vehicles, and nearly 5,000 of Germany’s most elite soldiers were motionless, transformed from a terrifying armored spearhead into a frozen, helpless traffic jam.

They were the tip of the spear for Hitler’s last great gamble in the West, the Battle of the Bulge. They were supposed to be smashing through American lines, racing for the Meuse River, and changing the entire course of the war. But now they were dead in the water. What could possibly stop such a force? What weapon had the Americans deployed to neutralize Germany’s finest so completely? The answer was both absurdly simple and profoundly terrifying.

The fuel gauges all read empty. This wasn’t just a logistical hiccup. It was a symptom of a terminal disease that had infected the entire German war machine. Peiper knew the plan was desperate from the start. His orders were not just to fight, but to hunt. The entire offensive was designed around a strategy of profound weakness.

They had to capture American fuel to survive. Germany, the nation that had perfected the Blitzkrieg, the lightning-fast mechanized assault, could no longer power its own machines. The plan was to literally run on the enemy’s gas as his men shivered in their stalled vehicles. Peiper gazed through the mist at the small village of Honsfeld.

It was an American supply depot, abandoned in haste. The GIs had fled so quickly they’d left coffee still warm and fires still burning. And there, lined up like a gift from the heavens, were rows upon rows of American jerry cans. Thousands of them. It was a miracle. A junior officer pried one open and sniffed. “Gasoline, Herr Obersturmbannführer. High octane.” The relief was electric.

His men scrambled from their vehicles, frantically beginning the work of refueling. Peiper walked through the enormous stockpile, doing the math in his head. 50,000 gallons. It was a staggering amount. Enough to fill every tank, every halftrack, every vehicle in his entire Kampfgruppe.

Enough fuel to get them to the Meuse River and perhaps beyond. In that moment, it felt like salvation. The offensive was back on. The war was still winnable. But as he stood amidst this incredible bounty, watching his elite SS soldiers pouring American fuel into the engines of German panzers, a cold, crushing realization began to dawn on him.

A question that would unravel everything he thought he knew about the war. “Why would the Americans just leave this here?” If they could afford to abandon what was to Germany a war-winning treasure, then what did that say about the enemy they were fighting? This wasn’t a miracle. It was a death sentence. To understand the profound shock Peiper felt, you have to understand the state of Germany in late 1944.

The Third Reich was running on fumes, literally. For months, Allied bombers had been systematically erasing Germany’s ability to produce fuel. The sprawling Leuna works, the heart of Germany’s synthetic fuel production, had its output slashed by over 95%. The refineries at Pölitz, Blechhammer, and Brüx were ghost towns operating at less than 10% capacity.

Albert Speer, Hitler’s armaments minister, had presented the Führer with reports showing in cold hard numbers that Germany could no longer wage a mobile war. The Luftwaffe was grounding its most advanced fighters, not for lack of pilots, but for lack of aviation fuel. Pilot training was slashed from hundreds of flight hours to a mere 60.

The mighty German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, was a ghost fleet, its battleships and cruisers rusting in port, unable to sail. On the home front, civilian traffic had been banned for years. Gasoline was a substance more precious than gold, and the Gestapo would launch full-scale investigations into the black market theft of a single liter.

The nation that had once conquered a continent was reverting to horsedrawn carts. Now, contrast that with the United States. In 1944, America didn’t just have an oil industry. It was the oil industry. The United States produced a staggering 1.8 billion barrels of crude oil that year. Germany, even counting all its synthetic plants and captured Romanian oil fields, produced just 33 million barrels.

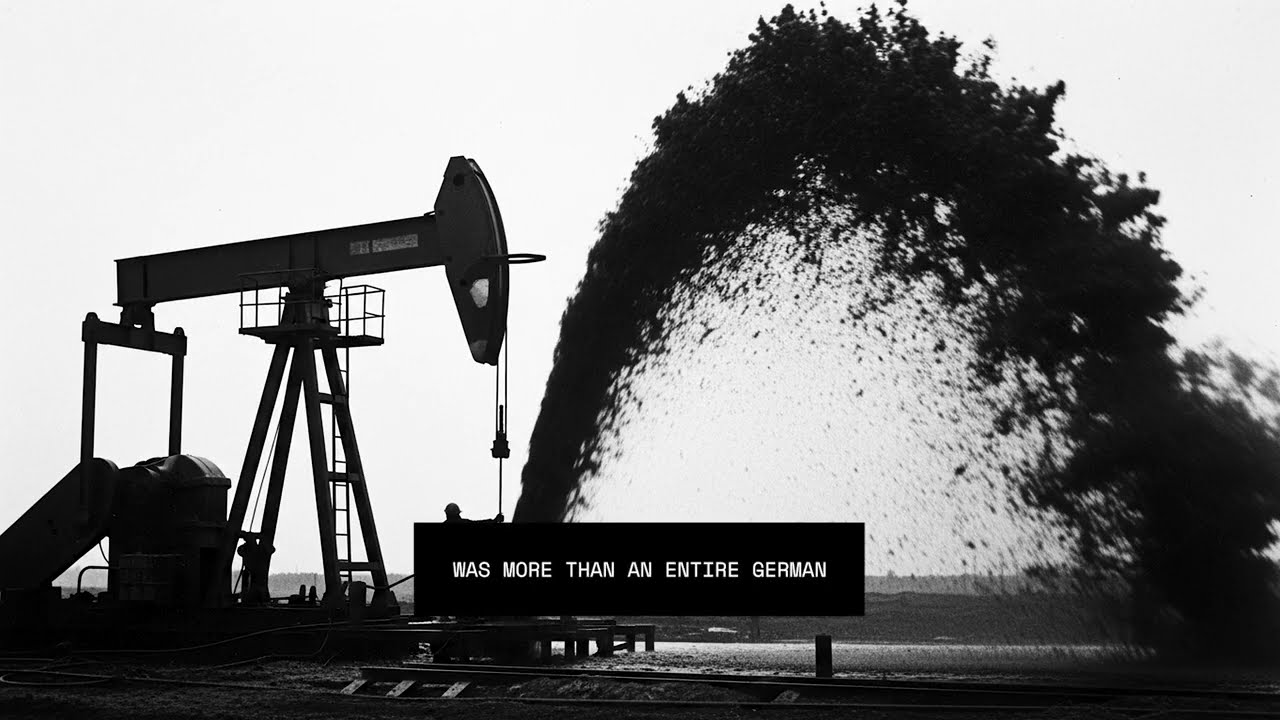

That’s less than 2% of American production. The East Texas oil field by itself produced more oil than all of Axis occupied Europe combined. This wasn’t a gap. It was a chasm. While German logisticians were rationing fuel by the liter, the Americans were dealing with a problem of such massive abundance that they had to invent new ways to move it all.

They built a system called the Red Ball Express, a fleet of nearly 6,000 trucks operating 24/7 on dedicated one-way highways across France, delivering over 12,500 tons of supplies to the front every single day. The fuel consumed by the trucks of the Red Ball Express alone was more than an entire German army group received in a month.

But even that wasn’t enough. So they performed an engineering miracle called Operation Pluto, Pipeline Under The Ocean. They laid flexible pipelines across the bottom of the English Channel, pumping over a million gallons of fuel directly from Britain to France every day. From there, a sprawling network of pipes spread inland, a circulatory system pumping the lifeblood of war directly to the front lines.

By December 1944, American forces in Europe were consuming 1.2 million gallons of fuel per day and their logistical network was delivering 1.4 million. They were fighting a massive high-intensity battle and still adding 200,000 gallons to their strategic reserves every single day. This was the context that Joachim Peiper was beginning to understand as his men refueled at Honsfeld.

His miraculous find of 50,000 gallons was less than 5% of what the Americans were pumping across the channel every single day. It was a rounding error. As his men worked, the evidence of this terrifying reality mounted. One of his sergeants, who could read English, found the shipping manifests in the abandoned depot office.

He brought them to Peiper. The papers detailed the journey of this gasoline from a refinery in Texas to a port in New York, across the Atlantic to Liverpool, across the channel to Normandy, and then trucked 400 miles to this tiny depot in Belgium. The entire journey of over 6,000 miles had taken less than 6 weeks.

Peiper read the documents, crumpled them in his fist, and said nothing. His face, according to the sergeant, went pale. Then another soldier found a stack of the American military newspaper, Stars and Stripes. The papers were dated December 15th, just 2 days old. The headline celebrated the opening of a brand new pipeline from Cherbourg to Verdun.

A pipeline capable of delivering 300,000 gallons of fuel per day. A single secondary pipeline was delivering six times more fuel every day than the amount Peiper had just captured and believed to be his salvation. The feeling of victory evaporated, replaced by a cold dread. They weren’t fighting another army.

They were fighting an industrial planet. With his tanks full of American gasoline, Peiper’s Kampfgruppe roared back to life and surged forward. They were back on schedule, a lethal spearhead once again. They smashed through the village of Büllingen, capturing more American supplies, food, ammunition, and most importantly, maps.

But the maps only deepened the horror. They showed the locations of other American fuel depots in the area. And they were everywhere. Every major crossroads, every small town seemed to have its own massive fuel stockpile. The US First Army alone had over 3.5 million gallons sitting in reserve depots just behind the front lines.

Peiper pushed on, his forces growing more desperate and brutal, committing the infamous Malmedy massacre where they murdered 84 unarmed American prisoners of war. Even this atrocity was born of logistical panic. Peiper would later claim he couldn’t spare the fuel to transport prisoners to the rear. By the evening of December the 17th, his advance guard reached the town of Stavelot.

And there they saw it, the ultimate prize, the largest American fuel depot in the entire sector. It contained over 2 million gallons of gasoline. Here was the fuel to get them not just to the Meuse, but all the way to Antwerp. Here was the fuel to win the Battle of the Bulge, but as the lead German tanks rumbled towards the depot, they saw American soldiers moving among the vast stacks of jerry cans.

They weren’t preparing a defense. They weren’t trying to evacuate the fuel. They were destroying it. Captain John Brewster of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion had received his orders: “Deny the fuel to the enemy at all costs.” His men worked frantically, pouring gasoline to create trails between the stacks and distributing white phosphorus grenades.

As Peiper’s tanks crested the hill overlooking the depot, Captain Brewster gave the order. A sergeant pulled the pin on a grenade and tossed it. The world erupted in fire. A wall of flame shot hundreds of feet into the air and within minutes the entire 15-acre depot was a raging inferno. A pillar of black smoke climbed thousands of feet into the winter sky, visible for 100 miles.

The fire would burn for three days, consuming enough fuel to have powered the entire German offensive to Antwerp and back again. Peiper stood on the turret of his command tank, watching the blaze in stunned silence. One of his men later recalled his words. He turned from the fire and said quietly, “They can afford to burn 2 million gallons just to deny them to us. What are we doing here?”

That question echoed across the Ardennes. All along the front, American engineers were doing the same thing. At Spa, they burned 2.5 million gallons. At Francorchamps, another million. In the first week of the battle, American forces deliberately destroyed over 8 million gallons of their own fuel to prevent it from being captured.

To the German High Command, this was an act of incomprehensible madness. 8 million gallons was more fuel than they had allocated for the entire offensive. It was an amount of energy that could have changed the strategic balance of the war. To the Americans, it was a sound tactical decision, a resource that was vast and crucially replaceable.

While Peiper’s men were now desperately siphoning the last drops of fuel from knocked out vehicles, American C-47 transport planes were flying hundreds of sorties to the besieged town of Bastogne, airdropping supplies, including 160,000 gallons of gasoline. The Americans were flying more fuel to a single surrounded garrison in a day than Peiper’s entire elite armored division possessed in total.

The realization spread like a virus from the front lines all the way to the top. General Hasso von Manteuffel, commander of the Fifth Panzer Army, wrote after the war, “When I learned the Americans had destroyed 8 million gallons of fuel, I knew the offensive had failed before it truly began.” The physical battle was still raging, but the psychological war, the war of industrial capacity, was over.

The numbers tell a story that no battlefield heroics could ever overcome. While Germany’s war machine was dying of thirst, America was drowning in oil. The contrast was present in every piece of equipment. A German Tiger tank burned 2.5 gallons per mile in combat. An American Sherman less than one. American trucks were standardized with interchangeable parts, making maintenance a simple, streamlined process.

The German army was a chaotic museum of captured equipment. French tanks that needed different lubricants. Soviet trucks that needed different spare parts. Each one a logistical nightmare that multiplied the difficulties. By December 20th, Peiper received a radio message that sealed his fate: “Fuel convoy destroyed by Allied aircraft. No resupply possible.”

He was trapped. He gathered his officers. One of them stated the grim reality: “We have fuel for perhaps 20 km. The Meuse is 30 km away.”

It was here surrounded and doomed that Peiper spoke the words that captured the essence of Germany’s defeat. “Gentlemen,” he said, “We have discovered we are fighting an enemy who burns more fuel to deny it to us than we received for this entire operation. What we captured at Honsfeld, which seemed like a miracle, was nothing to them. We cannot win.”

3 days later, on the night of December 23rd, the weather finally cleared. The Allied air forces, which had been grounded by fog, took to the skies. Over 2,000 sorties were flown that day. A P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bomber consumed 300 gallons of fuel per hour. A B-26 Marauder medium bomber burned 200 gallons. A single day of Allied air operations consumed more aviation fuel than the Luftwaffe had received for the entire month.

Under this aerial onslaught, Peiper’s position became completely untenable. That night he gave his final order. They were to abandon their vehicles. His men, the elite of the Waffen SS, destroyed their own priceless machines. They placed explosive charges inside their remaining 39 Tiger and Panther tanks, their 70 armored halftracks, and over a 100 other vehicles.

They drained the last few drops of fuel, not to fight, but to ensure the demolitions were complete. Then under the cover of darkness, Joachim Peiper and the 770 survivors of his original 5,000-man force slipped away on foot, retreating through the snow-covered forest like ghosts.

They left behind millions of Reichsmarks worth of Germany’s best military hardware. Defeated not by enemy guns, but by an empty fuel gauge. The story of Kampfgruppe Peiper and the 50,000 gallons of captured fuel is more than just a war story. It represents the brutal mathematical conclusion of industrial warfare.

It was the moment when the romantic myth of the superior German warrior, the idea that fighting spirit and tactical genius could overcome material disadvantage, finally died. It didn’t matter that a German soldier in 1944 was on average a more experienced combat veteran than his American counterpart. It didn’t matter that the Tiger Tank was in many ways superior to the Sherman.

None of it mattered because the war was no longer being decided by soldiers or generals, but by factories and refineries thousands of miles away. It was being decided by an unwininnable equation. In 1944, the Allies had a production advantage over the Axis of more than 5:1 in almost every category of equipment. But in petroleum, the lifeblood of modern war, that ratio was nearly 50 to 1.

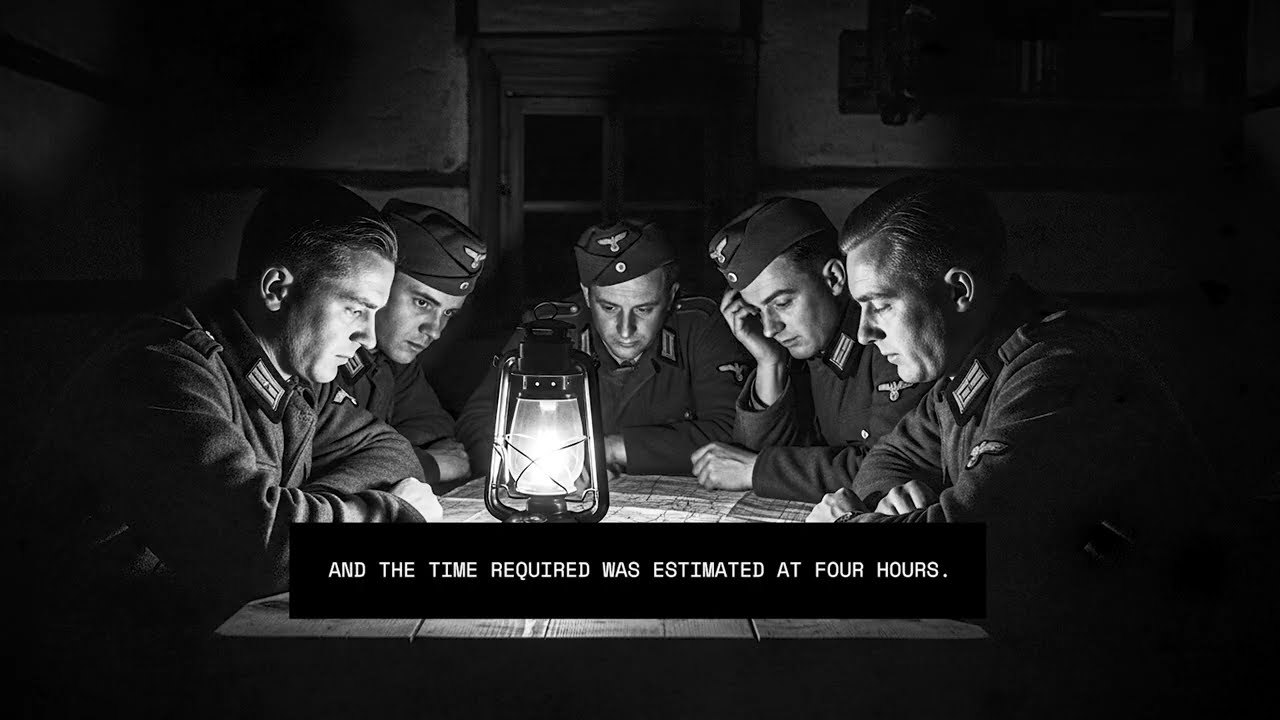

Germany was fighting a global superpower while having the logistical capacity of a small developing nation. When American salvage crews eventually reached Peiper’s abandoned vehicle park at La Gleize, they found dozens of perfectly operational tanks. The official report noted that to get all 39 tanks running again would require about 8,000 gallons of fuel.

The source for this fuel was listed as “local reserve” and the time required was estimated at “4 hours.” The amount of fuel that was an impossible division-saving treasure for the Germans was for the Americans a trivial logistical task that could be sourced locally and completed in an afternoon. That was the discovery at Honsfeld.

Not just that the Americans had more fuel, but that they operated on a completely different plane of reality. A reality where their waste was greater than Germany’s entire need. Today, one of Peiper’s abandoned King Tigers still sits in a museum in La Gleize, right where it ran out of gas. It’s a silent steel monument to a fundamental truth of modern conflict: “Courage is no match for logistics.”

News

He Kept Two Sisters Pregnant for 20 Years — The Darkest Inbred Secret of the Appalachians

They found them in the basement. 16 souls who had never seen sunlight. Their eyes reflecting back like cave creatures…

She Was Pregnant, But No One Knews Who — The Most Inbred Child Ever Born

In the autumn of 1932, a young woman walked into St. Mary’s Hospital in rural Virginia, her belly swollen with…

Wanted: Dead or Alive: Pancho Villa and the American Invasion of Mexico | Historical Documentary

On March 9th, 1916, US troops in the border areas of New Mexico and Texas were put on full alert…

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901)

In the spring of 1998, a surveyor working the eastern ridge of Cabell County, West Virginia, stumbled upon the foundation…

“Couple Disappeared in 2011 in the Minas Countryside — 8 Years Later, Bodies Found in Abandoned Mine…”

Imagine vanishing, not just getting lost, but truly disappearing off the map. And then, 8 years later, you are found…

The Moment Germany Realized America Was Built Different

For decades, the German High Command, the most respected and feared military mind in the world, studied America. They read…

End of content

No more pages to load