Couple Disappears on a Trail in Rio de Janeiro — 7 Years Later, Their Bodies Are Found Inside a Tree.

Roberto Silva adjusted his flashlight and directed the beam into the crack of the Centenary Jequitibá. What he saw made him recoil immediately, his heart racing. “My God!” he whispered, feeling his legs tremble. “Is there something in there?” There were deteriorated, bones.

And that definitely shouldn’t be there. In 15 years working in that forest, Roberto had never found anything like it. “Central! This is Roberto Silva.” He spoke into the radio, his voice trembling. “I need immediate backup. I found human bodies inside a tree.”

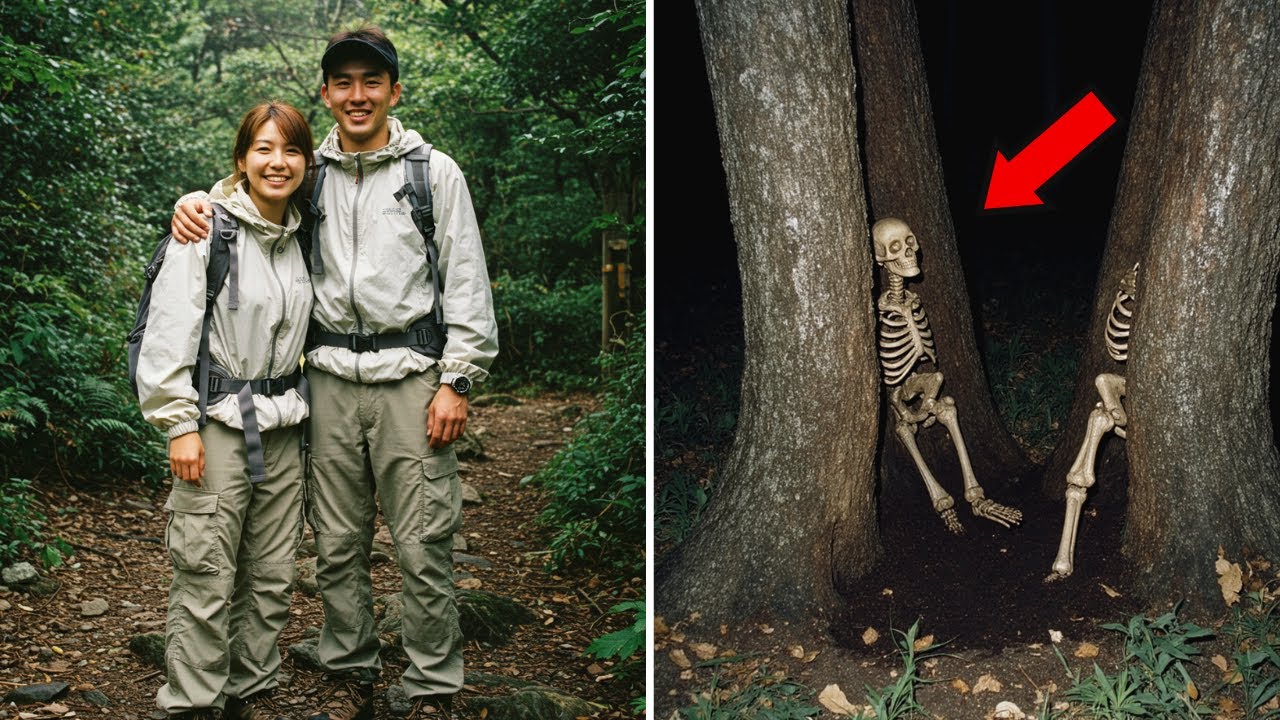

7 years earlier, Hiroshi and Yuki Tanaka had flown from Japan for a romantic honeymoon in Rio de Janeiro and simply vanished. The Japanese consulate, the Federal Police, even Interpol participated in the search. Now Roberto had just discovered where they had been all this time. But how did two Japanese tourists end up inside a Brazilian tree? And why did no one find them during seven years of intense searching? The answer would shock not only the families, but the entire international community.

It was a sunny morning in September 1997 when Roberto Silva, an experienced 38-year-old park ranger, decided to make his routine rounds on the Morro da Urca trail. After 15 years protecting Rio’s forests, Roberto knew every stone, every tree, every curve of those trails like the back of his hand.

On that specific morning, something different caught his attention. A centenary jequitibá, over 15 meters tall and with a trunk almost 3 meters in diameter, showed strange signs. Roberto stopped in front of the gigantic tree, frowning. There was a crack in the trunk he had never seen before, a vertical slit approximately 50 cm long, as if the wood had opened naturally over the years.

“What a strange thing,” murmured Roberto, approaching the tree. The ranger had passed by that same Jequitibá hundreds of times over the years but had never noticed that opening. Perhaps it was the result of the intense rains of the last few weeks that could have caused some change in the structure of the old wood.

Roberto took his flashlight and directed the beam of light into the slit. What he saw made him step back a few paces, his heart racing. There was something inside the tree, something that definitely shouldn’t be there. It looked like fabric, maybe clothes, but in an advanced state of decomposition. “My God!” whispered Roberto, feeling his legs tremble.

In a decade and a half working in that forest, he had already found dead animals, trash abandoned by irresponsible tourists, and even some suspicious situations. But that was different. That looked human. With trembling hands, Roberto took his radio communicator and made contact with the Municipal Guard base.

“Central. This is Roberto Silva, sector 7 of the Morro da Urca trail. I need immediate backup. I found something suspicious inside a tree. It could be criminal evidence.”

The response came quickly. “Roberto, confirm your exact location. Investigation team on the way. Do not touch anything and isolate the area.” Roberto marked the spot with isolation tape he always carried in his backpack and moved a few meters away from the Jequitibá.

While waiting for the team’s arrival, his mind began to make connections. Seven years ago, there was a case that deeply marked not only the tourism community of Rio de Janeiro but gained international repercussions. A young Japanese couple had disappeared without a trace after going out for a hike.

Hiroshi Tanaka, 28, an electronic engineer at Sony in Tokyo, and Yuki Tanaka, 26, an English teacher at a private school in Kyoto, had arrived in Rio on March 15, 1990, for a dream honeymoon. It was the couple’s first international trip, having married just two weeks earlier in a traditional ceremony in Osaka, Yuki’s hometown.

Hiroshi and Yuki were the typical modern young Japanese couple of the 90s: dedicated workers who saved for two years to realize their dream trip to Brazil. They were fascinated by Brazilian nature, especially the tropical forests that do not exist in Japan. In letters sent home, they shared their admiration for the lushness of Rio’s Atlantic Forest.

On that fateful afternoon of March 17, 1990, Hiroshi and Yuki left their hotel in Copacabana bound for Morro da Urca. They had planned to hike to the top to watch the sunset, a romantic activity Yuki had found in Japanese travel guides about Brazil. The plan was simple: go up in the morning, enjoy the view, have a picnic at the top, and come down before nightfall.

Yuki had prepared onigiri, Japanese rice balls, and Hiroshi carried an analog camera to document every moment of the adventure. The couple was last seen at 2:30 PM, when they bought water and cereal bars at a small stand near the start of the trail. The vendor, Mr. José, a 51-year-old man who had worked at the spot for over 10 years, remembered them perfectly.

“It was a different couple, you know?” Mr. José had told the police at the time. “Real Japanese, very polite. She tried to speak Portuguese, he spoke English with me. They bought water, some cereal bars, and asked about the best time to come down using gestures and loose words. I said it was better to start the descent around 5 in the afternoon before it got dark. They understood, thanked me doing that Japanese bow, but Hiroshi and Yuki were never seen again.”

At 10 PM that same night, when the couple did not return to the hotel, the manager called first the Military Police, then the Japanese consulate in Rio de Janeiro. The hotel manager, Mr. Fernando Macedo, an experienced man who had worked in the hotel sector for over 15 years, knew something was wrong.

“They were extremely organized,” Mr. Fernando explained to the investigators. “They left all documents tidied in the room safe. Money, cards, passports. They only took the essentials for the trail. And they told me specifically in English that they would return for dinner at 7 PM because they had a reservation at a Japanese restaurant in Ipanema that they had researched before the trip.”

The search operation was intense and international. Firefighters, municipal guard, Federal Police, volunteers, even Navy helicopters participated in the searches that lasted three weeks. The Japanese consulate assigned two employees to accompany the investigations full-time. Sniffer dogs covered every meter of the trail and adjacent areas.

Divers checked nearby lakes and streams. Mountaineering experts explored hard-to-reach areas. Nothing was found. The case gained international repercussions, especially in Japan. Correspondents from NHK, the Japanese public broadcaster, traveled to Rio de Janeiro to cover the case.

Hiroshi and Yuki’s parents flew from Tokyo and Kyoto to Brazil and remained in the city for almost two months with the help of consulate translators, distributing pamphlets with photos of the couple, giving interviews through interpreters, offering a reward for any information. At the time, without social networks as we know them today, dissemination depended on newspapers, television, and posters.

Even so, the case mobilized the worldwide Japanese community through letters and telegrams. Mr. Kenji Tanaka, Hiroshi’s father, was a 42-year-old Toyota engineer who had never left Japan before this tragedy. Through a translator, he always told journalists: “My son knew orientation very well and had hiking equipment. He knew how to use a compass and paper maps. They didn’t get lost. Something happened to them.”

Mrs. Akemi Yamamoto, Yuki’s mother, a 38-year-old primary school teacher, divided her anguish between hope and the cultural despair of being in a completely different country. “My daughter was athletic, practiced martial arts since childhood. If she were lost in the woods, she would have found a way to survive, to ask for help. The total silence… that’s not normal.”

Brazilian investigators worked in coordination with Interpol and Japanese authorities, exploring all possibilities. Accident? But where would the bodies be? Kidnapping? But there was no ransom demand. And although the couple had a comfortable financial condition in Japan, they were not rich by Brazilian standards. Xenophobic crime? But there was no evidence of racial conflict. Voluntary flight? But why would they leave all belongings, passports, and money at the hotel?

The delegate responsible for the case, Dr. Carlos Mendonça, a veteran with 15 years of experience in missing persons cases, publicly admitted that this was one of the most intriguing cases of his career, especially involving foreign citizens. “In a decade and a half investigating disappearances,” said the delegate in an interview for Jornal do Brasil in 1991, “I’ve never seen a case with so few traces involving international tourists. It’s as if Hiroshi and Yuki had simply evaporated from the face of the Earth.”

The diplomatic pressure made everything even more complex. The consul general of Japan in Rio de Janeiro, Mr. Takeshi Nakamura, personally followed the investigations and maintained constant contact with Brazilian authorities. “This case represents not only a family tragedy but also a matter of international tourism safety,” declared the Consul. “Brazil receives thousands of Japanese tourists annually, and cases like this can affect bilateral relations.”

As the months passed, media coverage gradually decreased. Other cases occupied the headlines. The families returned to Japan but never stopped searching. Mr. Kenji maintained regular correspondence with Brazilian authorities through letters, since the internet was still incipient in the early 90s.

The Japanese consulate kept the case as a diplomatic priority, sending semi-annual reports to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. The Japanese embassy in Brasília pressed for regular updates on the investigations. The years passed: 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996. Brazil went through economic turmoil. The implementation of the Real Plan, changes in government. And the case of Hiroshi and Yuki was gradually being archived in collective memory, but never forgotten by diplomatic authorities.

And then came that September morning in 1997. Roberto Silva was still standing beside the Jequitibá when he heard the noise of vehicles approaching. Three Civil Police cars, a van from the Institute of Criminalistics, an ambulance, and a Federal Police car came up the access road to the trail.

The first to arrive was investigator Paulo Henrique Cardoso, a 35-year-old man, a specialist in missing persons cases and fluent in English. “Roberto, show me exactly what you found,” said the investigator, already wearing gloves and putting on a mask.

Roberto led the team to the Jequitibá and pointed to the crack in the trunk. “It’s in there. I used the flashlight and saw what looks like clothes, maybe bones too. I didn’t touch anything.” Investigator Paulo directed a more powerful flashlight into the tree’s opening. What he saw confirmed the worst fears. There were clearly human remains inside the hollow of the Centenary Jequitibá.

“Dr. Marcos,” called Paulo, addressing the medical examiner who had just arrived. “You need to see this. And call the Japanese consulate. If it’s who I’m thinking, we’re going to have to notify the diplomatic authorities.”

Dr. Marcos Figueiredo, a medical examiner with 28 years of experience, approached the tree carefully. He was a meticulous man, known for his technical precision and sensitivity in dealing with victims’ families, especially in international cases.

“We’re going to need to open this tree very carefully,” said Dr. Marcos after examining the situation. “If there are indeed bodies in there and if they are the Japanese tourists, this will generate international repercussions. We need to preserve all possible evidence.”

The criminalistics team worked for over 4 hours to carefully open the side of the Jequitibá without damaging what was inside. A representative of the Japanese consulate, Mr. Hideaki Watanabe, arrived at the scene at 3 PM, accompanied by an official translator. Using specialized tools, they created a larger opening that allowed complete access to the tree hollow.

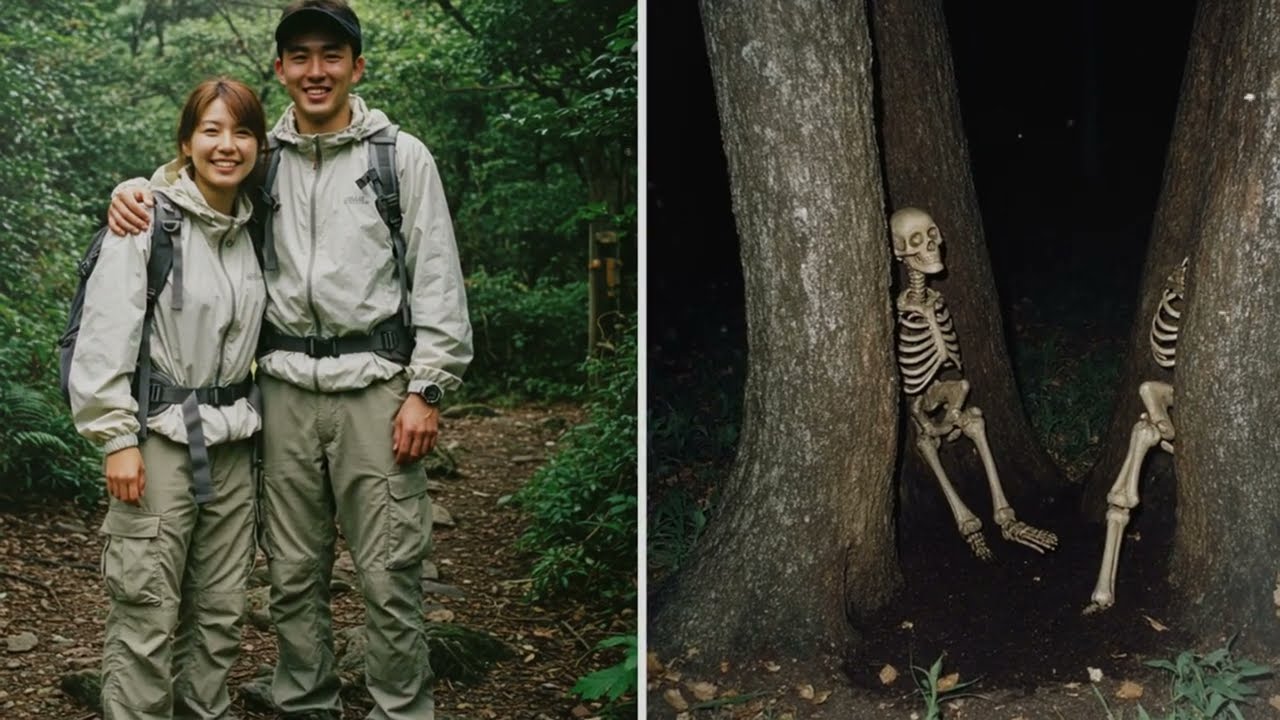

What they found inside left them silent for several minutes. Two human skeletons were positioned embracing each other inside the tree hollow. The clothes, although deteriorated by time and humidity, were still partially recognizable. One of the skeletons wore remnants of a t-shirt with Japanese characters, still vaguely visible, and men’s shorts. The other wore a light-colored blouse and women’s shorts.

But the most shocking thing was how the bodies were positioned. They didn’t seem to have been placed there after death. The position suggested they had entered the tree still alive and died inside, embracing one another. “How is it possible for two adult people to enter a tree?” asked one of the criminalistics technicians in a low voice, conscious of the Japanese representative’s presence.

“Dr.” Marcos carefully examined the internal structure of the Jequitibá. “Centenary trees like this can develop huge internal hollows,” he explained in English so the consular representative could understand. “It’s a natural process of heartwood decomposition. Some jequitibás have hollows so large they could shelter several people.”

Along with the skeletons, objects were found that helped with initial identification: a men’s leather wallet, a small Japanese-style women’s purse, a Nikon analog camera, and two Japanese passports in a waterproof plastic package. There were no cell phones, since in 1990 mobile phones were not yet common in Brazil or Japan.

Investigator Paulo carefully opened one of the passports. The name was clearly legible: Hiroshi Tanaka. The other passport confirmed: Yuki Tanaka. “My God!” whispered Paulo in English, looking at the consular representative. “It’s the Japanese couple from 1990.”

Mr. Watanabe from the consulate immediately made a call to Brasília informing of the discovery. Within minutes, diplomatic protocols were activated. The Japanese embassy in Brasília was notified, which in turn contacted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo. The news of the discovery spread quickly, first through diplomatic channels, then to the international press. Within hours, correspondents from NHK, the Japanese public broadcaster, were flying to Rio de Janeiro, 7 years after having covered the original disappearance.

Hiroshi and Yuki’s families were contacted via international phone lines by Japanese authorities who coordinated with the consulate in Rio to break the news simultaneously. Mr. Kenji Tanaka, now 49, received the call from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at his home in Tokyo. After 7 years, he had learned to fear official calls about his son.

“Mr. Tanaka,” said the formal voice in Japanese. “We believe they found Hiroshi-kun and Yuki-chan in Brazil. Two bodies were discovered along with their passports. We will need confirmation by examination. But…” Mr. Kenji broke down in tears. 7 years of uncertainty, of hope, of nightmares finally came to an end. It wasn’t the ending he had dreamed of, but it was an ending.

Mrs. Akemi Yamamoto, Yuki’s mother, now 45, received a similar call 30 minutes later. “I always knew they wouldn’t come back,” she said through tears. “But I hoped, I always hoped I was wrong.” The two families, accompanied by officials from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and consular representatives, flew to Rio de Janeiro the next day.

The identification process by medical examination would take a few weeks, but the passports and physical characteristics were already sufficient for a positive preliminary identification. While they awaited the final results, the question that haunted everyone was: how had Hiroshi and Yuki ended up inside a tree?

Dr. Marcos Figueiredo, after three days of analyzing the skeletons with the assistance of Japanese forensic specialists sent especially for the case, called an international press conference to present his preliminary conclusions. “Based on the examination of the bones and the position of the bodies,” explained the examiner in Portuguese with simultaneous translation into Japanese, “our hypothesis is that Hiroshi and Yuki entered the Jequitibá hollow voluntarily. There are no signs of violence, fractures caused by aggression, or evidence that they were forced into the tree.”

A journalist from TV Globo raised his hand. “Doctor, why would two people voluntarily enter a tree?”

“That is the central question,” replied Dr. Marcos. “We are working with some hypotheses. It could have been to protect themselves from some danger, like wild animals or ill-intentioned people. It could have been due to disorientation, if they were lost and panicked, or it could have been due to adverse weather conditions.”

Investigator Paulo, speaking in English for the international correspondents, added: “We are analyzing weather records from March 1990. During the week of the disappearance, there were several intense storms in the region. It’s possible they took shelter in the tree during heavy rain and became trapped inside.”

A correspondent from NHK asked in English: “But how could healthy adults become trapped inside a tree? Why couldn’t they get out?” This explanation did not fully satisfy. How would two healthy and prepared adults get stuck inside a tree? Why couldn’t they call for help? The answer came when the criminalistics team made a crucial discovery on the fourth day of investigation.

Examining the interior of the Jequitibá more carefully, they found evidence that the original entrance to the tree hollow had collapsed. “Look at this,” said criminal expert Dr. Fernanda Souza, pointing to a specific area of the tree. “There are clear signs that there was a larger opening here, but it was closed by a landslide of earth and debris.”

The theory began to form. Hiroshi and Yuki, possibly lost or trying to protect themselves from a tropical storm—a phenomenon nonexistent in Japan—found the opening in the trunk of the Jequitibá and decided to shelter inside. The tree hollow was spacious and dry, a perfect refuge for someone coming from a country without tropical forests.

But during the night or in the following hours, intense rains typical of Rio’s climate caused a small landslide on the slope near the tree. Mud, rocks, and debris blocked the entrance through which they had entered, trapping them inside the Jequitibá.

“It is a tragedy of cultural and geographical circumstances,” explained Dr. Marcos. “They probably tried to get out, but the opening was completely blocked. Without proper tools and with limited space to maneuver, and without experience with this type of tropical situation, they couldn’t open a new exit.”

The Nikon camera found with the bodies provided crucial additional clues. Although damaged by humidity, technicians managed to recover several images from the photographic films. The last photos showed Hiroshi and Yuki on the trail, smiling and happy, meticulously documenting every moment of the Brazilian adventure.

One of the images was dated March 17, 1990, the day of the disappearance, but there was a series of final photos taken with flash showing the interior of the Jequitibá hollow. They were photos of Hiroshi and Yuki, still smiling initially, but progressively more worried. The last images showed clear signs of despair.

“They were fine when they entered the tree,” noted investigator Paulo. “They weren’t injured or in initial panic. They probably thought it was a temporary shelter, as they do in mountains in Japan.”

Dr. Marcos estimated that Hiroshi and Yuki survived between four to six days inside the tree, based on dental wear indicating they chewed tree bark for nutrition, the presence of small improvised containers made with Japanese food packaging to collect rainwater, and evidence that they tried to dig an alternative exit with metal objects.

“They fought intelligently to survive,” said the examiner. “They used survival knowledge they must have learned through Japanese disaster preparedness culture. They didn’t give up easily.” The final position of the skeletons embracing each other suggested they spent their last moments together, comforting one another, a Japanese cultural tradition of facing death with dignity and unity.

The case had a massive international impact in the late 90s. The Brazilian government created special protocols for foreign tourists on trails. Maps were translated into Japanese, English, and Spanish. Emergency equipment was installed at strategic points on major Rio trails. The Japanese consulate collaborated with Brazilian authorities to create safety materials in Japanese for tourists, with detailed maps of the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region and information on emergency procedures.

The centenary Jequitibá where Hiroshi and Yuki were found was transformed into an international memorial. A plaque in Portuguese, Japanese, and English was installed near the tree with the following inscription: “In memory of Hiroshi and Yuki Tanaka, two souls who found in Brazilian nature both the adventure they sought and the eternal rest they did not expect. May their story inspire safety and preparation for all international adventurers who walk these paths.”

The families were finally able to hold the Buddhist ceremony they had awaited for 7 years. The funeral was held in Tokyo with the presence of the Brazilian ambassador to Japan, hundreds of friends, family members, and people who had followed the search during all those years. Mr. Kenji, in his speech at the funeral in Japanese, said through a translator: “My son and Yuki loved life, loved nature, loved each other. Knowing they spent their last moments together, embracing, following our tradition of facing difficulties united gives me a peace I didn’t expect to feel.”

Mrs. Akemi added: “7 years without knowing was a torture no mother should go through. Now I can truly mourn my daughter, I can visit her Buddhist altar, I can begin to accept that she has gone to the next plane of existence.”

The case also led to diplomatic agreements between Brazil and Japan on tourism safety. A registration system for foreign tourists on trails was created with check-in and check-out at specific points. Groups of international tourists must now inform both local authorities and their respective consulates of their hiking plans.

Roberto Silva, the ranger who made the discovery, received a commendation of honor from the Japanese consulate and continued working on Rio’s trails, but he never looked at a centenary Jequitibá the same way again. “Sometimes I think,” said Roberto in an interview for NHK six months later, “how many other stories do these ancient trees keep in silence? How many secrets are hidden in our forest waiting to be discovered? But now I know that our nature impresses so many visitors that sometimes they forget it can also be dangerous.”

Hiroshi’s Nikon camera was donated by the family to the National Museum as part of an educational project on trail safety for international tourists. The couple’s last photos are displayed along with information in multiple languages about safety equipment, trail planning, and emergency protocols. Mr. Kenji transformed his correspondence into a memorial archive, where he keeps letters exchanged with Brazilian authorities and documents about the case. The archive is now consulted by Japanese families who have lost loved ones abroad.

Investigator Paulo Cardoso was promoted to coordinator of international cases and said the discovery changed his perspective on missing foreign tourists. “I learned that cultural differences can turn manageable situations into tragedies. International tourists need special protocols.”

Dr. Marcos Figueiredo included the case in a scientific article on accidental deaths of foreign tourists in natural tropical environments, published in the International Journal of Legal Medicine. The study highlights the importance of specific safety equipment for tourists from temperate countries visiting tropical regions. The Japanese embassy in Brazil now offers safety sessions for all Japanese applying for tourist visas, including specific information about Brazilian nature and climatic differences.

Today, more than 25 years after the disappearance and 27 years after the discovery, the Morro da Urca trail receives thousands of international visitors monthly. Most stop in front of the Jequitibá Memorial, read the multilingual plaque, and reflect on the risks of adventures in foreign countries. Local guides always tell Hiroshi and Yuki’s story to tourists, especially Asians, not to scare them, but to educate them.

“They didn’t die because they were irresponsible,” explains Carlos Ferreira, a trilingual tour guide for 20 years. “They died due to a combination of inexperience with tropical climate and circumstances no one could predict. But this teaches us that international tourists need extra preparation.”

The centenary Jequitibá continues standing, majestic and silent, its deep roots and high branches touching the Rio sky. The opening where Hiroshi and Yuki were found was sealed by conservation specialists, but the tree remains as a living reminder of an international love story that not even death could separate.

And every morning, when Roberto Silva makes his rounds on the trail, he stops in front of the Jequitibá Memorial for a few minutes, removes his hat as a sign of respect, and whispers a small prayer for the two young Japanese who found in Brazilian nature both the adventure they sought and the eternal rest they did not expect.

The investigations were officially closed in December 1997, with the conclusion that Hiroshi Tanaka and Yuki Tanaka died of accidental causes, trapped inside a centenary Jequitibá after a landslide blocked their only escape route. The final report sent simultaneously to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Interpol highlighted that the tragedy was the result of a combination of factors: inexperience with tropical climate, lack of adequate emergency communication equipment for the dense forest, and an unpredictable natural event.

The Japanese government used the case to reformulate its safety guidelines for citizens on international trips. Now, all Japanese visiting tropical countries receive a specific manual on natural risks and mandatory safety equipment. Brazil, in turn, implemented the Tanaka Protocol, a set of safety measures specific for Asian tourists, including mandatory trilingual guides on trails classified as dangerous and communication equipment available for rent at tourist spots.

Two years after the official closure of the case, a delegation of Japanese families who lost loved ones in international accidents visited the Jequitibá memorial. Mr. Kenji and Mrs. Akemi led the ceremony which included the planting of a Japanese cherry tree next to the Centenary Jequitibá, symbolizing the union between the two cultures and the hope that future tragedies be avoided.

“Hiroshi and Yuki became bridges between our countries,” said Mr. Kenji during the ceremony with simultaneous translation. “Their death was not in vain if it saves other lives through greater awareness and preparation.” The Japanese cherry tree, which blooms every year between August and September in the southern hemisphere, has become an additional symbol of the memorial. Japanese tourists frequently visit the site during the flowering in a silent pilgrimage that unites mourning and hope.

In 2024, almost 35 years after the disappearance, the Tanaka memorial remains one of the mandatory stops for Asian tourists visiting Rio de Janeiro. Hiroshi and Yuki’s story is told in Japanese schools as an example of preparation and awareness in international travel. Roberto Silva, now retired at 65, still visits the memorial weekly.

“That September morning in 1997 changed not only my life but the way Brazil receives foreign tourists,” he reflects. “Sometimes, tragedies teach us lessons that save future lives.” The Centenary Jequitibá and the Japanese cherry tree grow side by side, their roots intertwining in the Rio soil. Two species from distant countries, united forever by the story of love and tragedy of Hiroshi and Yuki Tanaka, the Japanese couple who found in Brazilian nature both the adventure they sought and the eternal rest they never expected. This is a completely fictional story, created for entertainment purposes.

News

Nazi Princesses – The Fates of Top Nazis’ Wives & Mistresses

Nazi Princesses – The Fates of Top Nazis’ Wives & Mistresses They were the women who had had it all,…

King Xerxes: What He Did to His Own Daughters Was Worse Than Death.

King Xerxes: What He Did to His Own Daughters Was Worse Than Death. The air is dense, a suffocating mixture…

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil

A 1912 Wedding Photo Looked Normal — Until They Zoomed In on the Bride’s Veil In 1912, a formal studio…

The Cruelest Punishment Ever Given to a Roman

The Cruelest Punishment Ever Given to a Roman Have you ever wondered what the cruelest punishment in ancient Rome was?…

In 1969, a Bus Disappeared on the Way to the Camp — 12 Years Later, the Remains Were Found.

In 1969, a Bus Disappeared on the Way to the Camp — 12 Years Later, the Remains Were Found. Antônio…

Family Disappeared During Dinner in 1971 — 52 Years Later, An Old Camera Exposes the Chilling Truth…

Family Disappeared During Dinner in 1971 — 52 Years Later, An Old Camera Exposes the Chilling Truth… In 1971, an…

End of content

No more pages to load