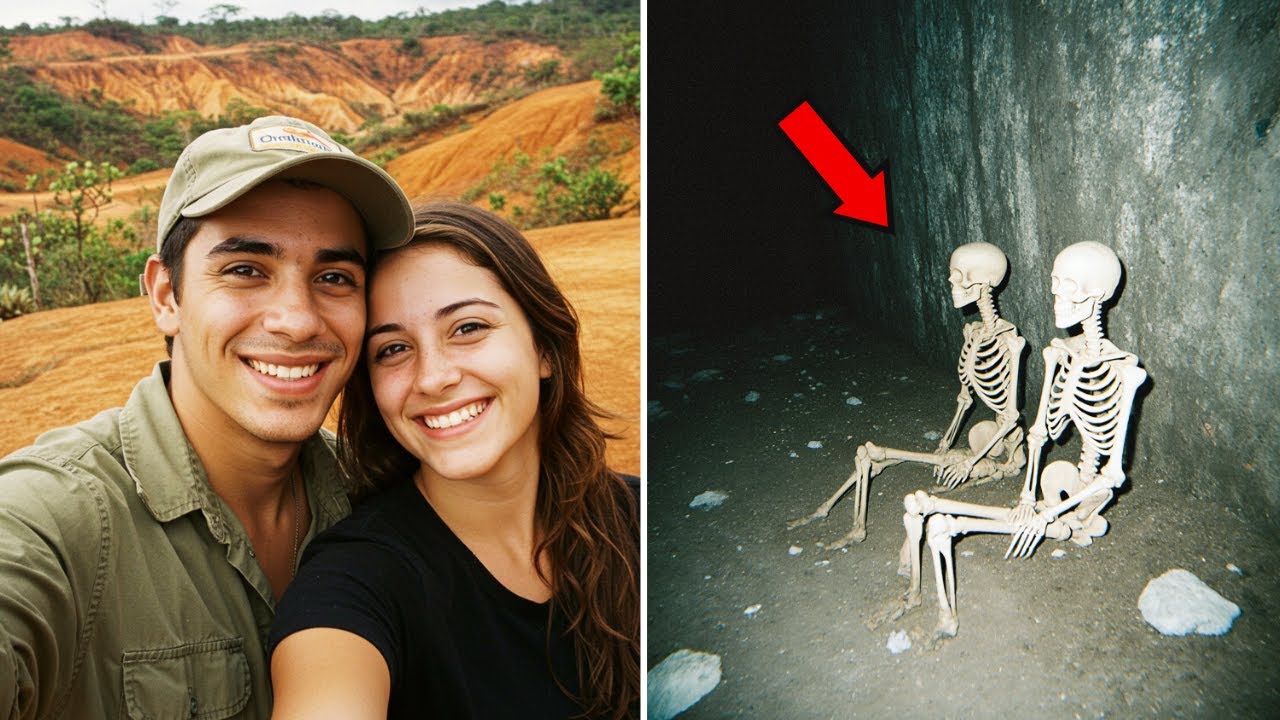

Imagine vanishing, not just getting lost, but truly disappearing off the map. And then, 8 years later, you are found not in a forest or at the bottom of a river, but in an abandoned mine sealed from the inside. You are sitting against the wall next to the love of your life, as if you had simply fallen asleep. But you are dead, and the bones in your legs are broken.

This isn’t a story about movie monsters. This is the true story of Marina and Bruno. A story about how a romantic weekend in the interior of Minas Gerais turned into an 8-year mystery, the answer to which was more terrible than anyone could have imagined.

The March sun of 2011 beat down on Marina Silva’s small apartment in Belo Horizonte as she finished packing her backpack for the third time. At 24, she worked as a nurse at the Hospital das Clínicas and was looking forward to the weekend she had planned with such care. Bruno Almeida, 26, arrived promptly at 6 a.m., driving his blue 2005 Corsa. As a mining technician, he knew the roads of the Minas interior well, especially the Congonhas region, where the old deactivated iron mines were located.

That was exactly where they were going. “Ready for our adventure?” asked Bruno, kissing Marina on the forehead. “More than ready,” she replied, adjusting her backpack strap. “It’s been a while since we left BH.” The plan was simple: Three days camping in a rural area near Congonhas, photographing the historic landscapes of the old iron mines, and enjoying time together away from the city rush.

Marina had borrowed a tent from her brother. Bruno had brought his new camera, and both were excited like teenagers. Before leaving, Marina sent a message to her older sister, Carla: “Leaving now with Bruno. Back Sunday night. Love you.” That was the last message anyone in the family received from them.

They left Belo Horizonte via BR-040 heading towards Congonhas. Bruno had studied a detailed map of the region and chosen a specific spot, a rural area near old 20th-century iron mines, now abandoned. The region was known to locals but rarely visited by tourists.

“It’s going to be perfect for photos,” Bruno explained as he drove, “and it has an incredible view of the valley.” Marina smiled, watching the Minas landscape unfold through the window: green mountains, small colonial towns, and occasionally, the marks of old mining operations that characterized that region. The weekend passed, Sunday arrived, and Marina and Bruno did not return home.

Initially, no one was worried. Perhaps they had decided to extend the trip by a day. It happens. But when Monday arrived and neither Marina appeared at the hospital nor Bruno at the mining company where he worked, the alarms began to ring. Carla, Marina’s sister, was the first to act. She called her sister’s cell phone.

“The number you have dialed is unavailable or out of coverage area.” She tried Bruno. Same result. On Tuesday, after consulting friends and family without getting any leads, Carla and Bruno’s parents went to the Belo Horizonte police station to report the disappearance. “They went camping near Congonhas,” Carla explained to the chief.

“They should have been back Sunday night.” The police chief, experienced in cases of people lost in the countryside, took note of the details. “Miss, I’ll be direct. The region you mention is extensive. It has forests, hills, old abandoned mines. If they got lost or the car broke down on a dirt road…” He didn’t finish the sentence, but the meaning was clear.

On Wednesday, a search operation was organized. Firefighters, Military Police, Civil Defense, and dozens of volunteers mobilized. The family had provided information about Bruno’s blue Corsa and the approximate region where they intended to camp. The first days of the search were intense. Helicopters flew over the region.

Ground teams scoured dirt roads and trails. Sniffer dogs were used. The expectation was to find them quickly. Maybe hurt, maybe with a broken-down car, but alive. The search region was challenging. Old mining roads crisscrossed amidst the vegetation of the Minas savanna. Abandoned mines dotted the landscape, some sealed, others merely fenced off with deteriorated barbed wire.

It was a labyrinth of possibilities. On the fifth day of the search, when hope began to dwindle, the fire department helicopter spotted something: a metallic reflection on an abandoned dirt road, almost hidden by vegetation. It was Bruno’s blue Corsa. The car was stopped in the middle of a road leading to old mining facilities.

The initial impressions were confusing. The vehicle showed no signs of an accident, the doors were unlocked, and the interior seemed untouched. Corporal Mendoza of the Fire Department was one of the first to examine the vehicle. “The tank was empty,” he reported later. “Completely dry. The car’s GPS showed a route continuing down this road to an old iron mine.”

In the back seat, they found the camping backpacks untouched. In the glove compartment, Bruno’s wallet with money and documents. On the passenger seat, Marina’s cell phone with 60% battery. “If they were in danger, they would have called someone,” Corporal Mendoza observed. But there were no missed calls, no attempts at contact.

The GPS indicated a specific direction: Mina Santa Rita, an old iron extraction site deactivated in the 1990s. The road continued for another 3 km to get there. The search teams immediately followed the location indicated by the GPS. Mina Santa Rita was an abandoned complex. Deteriorated concrete structures, rusted equipment, and several entrances sealed or partially blocked.

“Marina, Bruno!” shouted the firefighters, their voices echoing through the abandoned tunnels. Silence. They examined every accessible entrance, every structure where the couple could have sought shelter. They found old soda cans, teenager graffiti, but no sign of Marina and Bruno. The search extended for another week.

Every meter of the region was inspected, every possibility explored. Divers checked old flooded pits. Spelunkers went down into the safer mines. Even psychics were consulted by the desperate families. Nothing. It was as if Marina and Bruno had simply materialized in the middle of the dirt road and then vanished into thin air.

Gradually, the official searches were scaled back. The case was transferred to the Civil Police as a missing persons case. Photos of Marina and Bruno began to appear on utility poles and in supermarkets with the question no one could answer: “Have you seen them?”

Eight years passed. For Marina and Bruno’s families, every birthday, every Christmas, every special date was a renewal of pain. The absence of answers was perhaps worse than the certainty of death. At least death would allow for mourning, burial, and closure. Carla, Marina’s sister, never completely gave up. She maintained a Facebook group called “Looking for Marina Silva and Bruno Almeida,” which gathered over 15,000 people. She regularly posted updates, theories, and pleas for information.

“8 years without news,” she wrote in a March 2019 post. “If you are alive, if someone is holding you captive, please find a way to let us know. If anyone knows what happened, have mercy on our families.” Dona Rita, Bruno’s mother, had developed a habit of visiting psychics and fortune tellers. “He is alive,” she insisted at family gatherings.

“My mother’s heart feels that he is alive.” Bruno’s father, Seu José, was more pragmatic. “Rita, it’s been 8 years. If they were alive, they would have found a way to let us know.” At the police station, the case remained officially open, but in practice, it was shelved. The detective in charge had retired. The documents were archived, and new emergencies occupied the police’s attention.

Occasionally false leads appeared. Someone swore they saw a couple looking like them in another city. A psychic claimed to know where they were. An anonymous alleged kidnapper sent messages demanding ransom. All turned out to be hoaxes or delusions. The region where they disappeared continued its normal life. Farmers cultivated their lands.

Some mines returned to operation on a small scale. Occasional tourists visited the historical sites. The story of Marina and Bruno became a local legend. The couple who became “enchanted” in the old mines. “There are people who swear they hear voices in the mines at night,” said Zé Pequeno, owner of the bar in the nearest town. “They say it’s the two of them calling for help,” but for most people, Marina and Bruno were just a sad memory, a story about the dangers of venturing into the wilderness alone.

And so the years passed, until two scrap metal collectors decided to try their luck at the old facilities of the Santa Rita mine. Valdecir Santos, 38, and his cousin Jaíson, 42, were neither adventurers nor detectives. They were scrap collectors living on the outskirts of Congonhas and knew that the old mines hid treasures of iron and other sellable metals.

“That region has a lot of abandoned iron,” Valdecir explained later. “Old rails, structures, pipes. You just have to know where to look.” On a Wednesday in August 2019, they loaded their Kombi van with tools, blowtorches, crowbars, hammers, and headed towards Mina Santa Rita. They didn’t know the story of Marina and Bruno.

To them, it was just another job site. They arrived at the mine around 9 a.m. The place was exactly as the firefighters had left it 8 years earlier. Silent, deteriorated, apparently abandoned. “Let’s start with that entrance over there,” said Jaíson, pointing to a side tunnel that looked promising.

When they approached, they noticed something strange. The entrance, which should have been open or blocked with boards and wire, was sealed with a welded iron plate. “This is weird,” muttered Valdecir. “Who seals a mine from the inside?” Normally, abandoned mines are sealed with concrete and signposted by the DNPM, the National Department of Mineral Production.

That sealing looked improvised, almost clandestine. For the collectors, however, the iron plate was valuable in itself. They spent two hours cutting with a blowtorch until they opened a passage large enough for a person. When the last cut was made, a stale, cold air escaped from the opening. It was the kind of air that only exists in places that have been closed for a long time.

Valdecir turned on his flashlight and illuminated the interior. “Jaíson,” he called in a strange voice. “Come here.” Jaíson approached and looked through the opening. In the flashlight beam, about 15 meters into the tunnel, two human figures were sitting leaning against the wall. “Those are people,” whispered Jaíson. “Dead people,” corrected Valdecir.

They didn’t enter immediately. They stood there, processing what they saw. The two figures were in an almost peaceful position, a man and a woman sitting side by side, as if they were resting. “We have to call the police,” said Jaíson. “We have to,” agreed Valdecir. They left the mine, drove to a point where they could get a cell signal, and called the Military Police of Congonhas.

“Hello, police! Yeah, we were collecting scrap metal at the Santa Rita mine and found… found two dead people inside here.” The news of the discovery at the Santa Rita mine spread like wildfire. In a few hours, the site was surrounded by Civil Police cars, fire department, forensics, and inevitably journalists.

Detective Marcelo Arruda of the Civil Police of Congonhas took personal charge of the case. He vaguely remembered the disappearance from 8 years ago but hadn’t made the immediate connection. “Two people found in a sealed mine,” he noted in his pad. “First suspicion: Accident.” The initial forensic observations were intriguing.

The bodies were in an almost serene position, sitting leaning against the rock wall. Decomposition had been slowed by the dry mine air, preserving clothes and physical features. “White male, approximately 25-30 years old, dark hair,” dictated criminal expert Dr. Fernanda Reis. “White female, approximately 25 years old, long brown hair, clothing compatible with outdoor activities.” Dr. Henrique Costa, the medical examiner in charge, made the first observations on site. “No evident signs of external violence, no visible stab or gunshot wounds.”

But when the bodies were removed for detailed examination, the findings became disturbing. “Both victims present multiple fractures in the lower limbs,” reported Dr. Costa after the autopsy. “Complete fracture of the right tibia in the male, fractures of the tibia and fibula in the female. Fractures consistent with a fall from a considerable height.”

Detective Arruda frowned. “Fall from a height inside a horizontal mine?” The answer came when the technical team minutely examined the mine’s structure. Above the place where the bodies were found, there was a vertical opening. A shaft rising towards the surface. “It’s a vent for the old mine,” explained engineer João Batista, called to advise the investigation. “These openings served for ventilation during operation. This one is approximately 8 meters deep.”

A new theory began to form. Marina and Bruno had not entered the mine through the side entrance. They had fallen through the vertical vent. “Probably on the surface there was some deteriorated covering,” the engineer continued. “Old boards, vegetation.” They stepped without realizing it and plummeted. That would explain the broken legs. An 8-meter fall onto solid rock would certainly cause serious injury.

But it didn’t explain the most disturbing part: How had the side entrance been sealed from the inside? Analysis of the iron plate revealed chilling details. The welding had been done professionally, with proper equipment. More importantly, it had been done from the interior of the mine. “Someone was inside the mine when this plate was welded,” concluded welding expert Antônio Ferreira. “Impossible to do this kind of work from the outside.”

Detective Arruda felt a chill. “Are you saying someone locked these people inside the mine?” “I’m saying the welding was done from inside. How that person got out afterwards, I can’t say.” The investigation gained new urgency. This was no longer an accident, but a possible homicide. Two young people had fallen into the vent, were injured and helpless, and someone had taken advantage to imprison them there until they died.

Analysis of the skeletons revealed even more macabre details. Dr. Costa, the medical examiner, found marks on the bones indicating survival after the fractures. “The fractures show signs of an inflammatory process,” he explained to the detective. “This means they survived days, maybe weeks after the fall.” “Are you saying they died of hunger and thirst?” “Of dehydration, probably. It is a slow death.”

The question haunting everyone was: “Who would do something so cruel? And how did that person get out of the mine after sealing the entrance?” The answer came when they found the maps. The investigation into the ownership of the Santa Rita mine revealed a crucial detail. Although the mine was officially deactivated and belonged to the state, the surrounding area was leased for agricultural activities.

The lessee was Osvaldo Pereira Neto, 67, who lived alone on a small rural property 15 km from the mine. Neighbors described him as a solitary and temperamental man who did not like visitors or intruders. “He was always weird,” said Dona Geralda, who lived on the nearest property. “Doesn’t talk to anyone, doesn’t go to town. When someone passes near his land, he comes out with a shotgun in hand.”

When the police went to question Osvaldo about the events at the mine, he initially denied any knowledge. “I never go to that mine,” he insisted. “It’s dangerous, it could collapse.” But a search of his property revealed devastating evidence.

In the makeshift workshop behind his house, they found welding equipment, a blowtorch, electrodes, even a portable generator. In a locked cabinet, they discovered detailed maps of the Santa Rita mine tunnel network, including vents and passages that even official records did not show. “Where did you get these maps?” asked Detective Arruda.

Osvaldo remained silent. The most incriminating evidence was found in a dresser drawer: Photographs, dozens of photographs of tourists and curious people who had visited the region over the years, and among them, a photo of Marina and Bruno next to the blue Corsa. Confronted with the evidence, Osvaldo finally confessed, but his version of events was cold and devoid of remorse.

“They invaded my property,” he said during the interrogation. “They were camping where they shouldn’t, making noise, dirtying everything.” According to his account, he had observed Marina and Bruno camping near the mine vent. During the night, when they moved away from the camp to fetch firewood, Osvaldo removed the deteriorated covering of the vent and placed branches and leaves over it, creating a trap.

“I just wanted to scare them,” he alleged. “Wanted them to go away.” When Marina and Bruno returned the next morning, they stepped on the trap and plummeted into the vent. Osvaldo went down through the side tunnel and found them injured but alive. “They were moaning, asking for help.” He continued, without showing emotion, “But I couldn’t let them out. They were going to report me.”

Instead of calling for help, Osvaldo went home, got his welding equipment, and sealed the side entrance of the mine. Then he exited through a secret passage only he knew, an old ventilation tunnel that emerged almost 1 km away. “I went back a few days later to see if they had stopped making noise.” He admitted, “Everything was already quiet.”

The confession shocked even experienced police officers. Osvaldo had condemned two young people to a slow and agonizing death simply because they trespassed on land that wasn’t even his. “Do you understand that they suffered for days?” asked the detective. Osvaldo shrugged. “Their problem. Shouldn’t have entered where they weren’t invited.”

The trial of Osvaldo Pereira Neto became one of the most followed criminal cases in the region. Prosecutor Juliano Vasconcelos asked for a conviction for qualified homicide with three aggravating factors: frivolous motive, cruel means, and use of resources that hindered the victims’ defense.

“The defendant created a situation of absolute despair for Marina Silva and Bruno Almeida,” argued the prosecutor during the trial. “They spent days, possibly weeks injured, hungry and thirsty, in total darkness, knowing they were going to die.” The defense tried to claim mental disturbance and legitimate defense of property, but the evidence was undeniable.

Osvaldo had premeditated the crime, executed it coldly, and lived normally for 8 years, while two families agonized without answers. Carla, Marina’s sister, gave an emotional testimony. “For 8 years, we lived in the hope that they were alive somewhere. It was torture, but at least it was hope. Discovering they died this way, that this man left them to rot in a mine as if they were garbage…” She couldn’t finish the sentence.

Dona Rita, Bruno’s mother, was even more direct. “I would prefer my son had died in a car accident. At least it would have been quick. This monster tortured our children to death.” In December 2020, Osvaldo Pereira Neto was sentenced to 35 years in closed prison.

Judge Antônio Carlos Magalhães was severe in the sentencing. “The defendant demonstrated extreme coldness and cruelty. He not only caused the death of the victims but subjected them to prolonged and unnecessary suffering. Society needs to be protected from individuals capable of such inhumanity.”

Marina Silva and Bruno Almeida were finally buried in separate ceremonies in Belo Horizonte. Hundreds of people attended the funerals, including many who had participated in the searches 8 years earlier. Father Roberto, who celebrated Marina’s mass, summarized the general feeling: “Today is not a day of celebration, but of relief. At least now their families can mourn properly, knowing that justice has been done.”

Mina Santa Rita was permanently sealed by the DNPM with concrete and warning signs. A small memorial plaque was installed at the site in memory of Marina Silva and Bruno Almeida, whose lives were interrupted by human cruelty. “May their story serve as a warning about the dangers of intolerance and violence. 2011-2019.”

Two years after the trial, Carla created the NGO “Marina and Bruno – Alive in Memory,” dedicated to supporting families of missing persons and pressing for more effective investigations. “The police could have found my siblings in 2011,” she said during a lecture on the case. “If they had investigated the property better, questioned the lessee, examined the mines more carefully.”

8 years of suffering could have been avoided. The story of Marina and Bruno became a landmark in the discussion about search protocols and follow-up of disappearance cases in Minas Gerais. New guidelines were implemented, including mandatory investigation of private properties in the search area.

Osvaldo remains imprisoned at the Ribeirão das Neves penitentiary. According to staff reports, he maintains the same coldness demonstrated during the trial, refusing to participate in rehabilitation programs or show any regret. “He still believes he did nothing wrong,” reported prison psychologist Dr. Márcia Leite. “In his distorted mind, he was just defending his property from invaders.”

For the families, the healing process continues. Dona Rita, Bruno’s mother, developed a social project offering free psychological support for families of the missing. “If our pain can help other families endure the wait, then it has some purpose.”

The story of Marina and Bruno serves as a grim reminder that sometimes evil comes not from supernatural forces or professional criminals, but from seemingly ordinary neighbors, consumed by paranoia and the total absence of human empathy.

In their graves in the Belo Horizonte cemetery, side by side as they planned to be in life, Marina Silva and Bruno Almeida finally rest in peace. Their deaths were not in vain if they can prevent other families from going through the same agony of 8 years without answers. The love that united them in life and death prevailed over the cruelty that tried to erase them from memory. And perhaps that is the true victory in such a devastating story: proof that even the most extreme human wickedness cannot completely destroy the bonds of true love.

This story, although based on real elements of disappearance cases, is a work of fiction created for educational and awareness purposes regarding search protocols and the importance of more effective investigations in missing persons cases.

News

He Kept Two Sisters Pregnant for 20 Years — The Darkest Inbred Secret of the Appalachians

They found them in the basement. 16 souls who had never seen sunlight. Their eyes reflecting back like cave creatures…

She Was Pregnant, But No One Knews Who — The Most Inbred Child Ever Born

In the autumn of 1932, a young woman walked into St. Mary’s Hospital in rural Virginia, her belly swollen with…

Wanted: Dead or Alive: Pancho Villa and the American Invasion of Mexico | Historical Documentary

On March 9th, 1916, US troops in the border areas of New Mexico and Texas were put on full alert…

The Hollow Ridge Widow Who Forced Her Sons to Breed — Until Madness Consumed Them (Appalachia 1901)

In the spring of 1998, a surveyor working the eastern ridge of Cabell County, West Virginia, stumbled upon the foundation…

The Moment Germany Realized America Was Built Different

For decades, the German High Command, the most respected and feared military mind in the world, studied America. They read…

The $200 Million Nightmare: Inside ‘Project B’ and the Saudi-Backed Bid to Lure Caitlin Clark Away from the WNBA

Three months ago, the idea of Caitlin Clark leaving the WNBA seemed laughable. She is the face of the league,…

End of content

No more pages to load