WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded

In the stunned aftermath of Pearl Harbor as Japanese naval flags flew high across the Pacific, the Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo gathered to ask a simple, brutal question: What next? The maps were unrolled. The victories were tallied, but one man, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, knew a secret. It wasn’t about the ships he’d just sunk.

It was about the nation he had awakened. What he told the High Command wasn’t just a warning. It was a terrifying admission that a full-scale invasion of the United States was already impossible. The reason why would chill them to the bone. And it had almost nothing to do with the U.S. Army. This is the story of what Japan’s High Command said, and what they truly feared when they realized America couldn’t be invaded.

In the final days of 1941. The mood in Tokyo was electric. The Empire of Japan stood at the pinnacle of its power. The attack on Pearl Harbor had been, from their perspective, a staggering success, crippling the American Pacific Fleet in a single, decisive blow. General Hideki Tojo, the Prime Minister, and the military hardliners saw a path to victory that seemed all but certain.

Their armies were sweeping across Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, Malaya, the Philippines. They were falling like dominoes. The British were reeling. The Dutch were in disarray. An America they believed had just been dealt a knockout punch. This was the era of the “Victory Disease,” a wave of national hubris that swept through the Japanese command.

They had come to believe their own propaganda. They believed the Japanese “Bushido” spirit. The will of the warrior was spiritually superior to the soft, decadent, materialistic culture of the West. They viewed Americans as merchants and farmers, not fighters. A nation divided, unwilling to pay the price in blood of people who would surely sue for peace once their fleet was at the bottom of the sea.

Their plan, the Kessen doctrine, was built on this very assumption. It called for a single decisive fleet action. A winner-take-all battle that would so devastate the American Navy that Washington would have no choice but to negotiate a truce, leaving Japan as the undisputed master of Asia and the Pacific. But inside the heavily guarded walls of the Imperial General Headquarters, one man did not share in the celebration.

He knew the truth. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, was the very architect of the Pearl Harbor attack. Yet he was perhaps the most American-educated man in the entire Japanese government. He was a paradox, a patriot who deeply mistrusted the army’s aggressive plans and a brilliant naval strategist who now feared he had sealed his nation’s doom.

You see, Yamamoto had not just visited America. He had lived there. He studied at Harvard University from 1919 to 1921. He later served as a naval attaché in Washington, D.C. He hadn’t just seen the monuments and the politicians. He had traveled the country. He had driven from the East Coast to the West. He had seen the small towns, the vast farmlands and the roaring factories of the industrial heartland.

He spoke the language. He read the papers, and he understood the American psyche in a way that Tojo and the army generals simply could not. While the others celebrated, Yamamoto was writing in his diary. He famously wrote to a colleague, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.

” The High Command, however, was already looking past the Kessen doctrine. They were looking at the maps and asking the logical next question: What if we don’t just defeat America? What if we invade them? What would it take to land the Imperial Japanese Army on the shores of California? This is where the story truly begins.

Because when Yamamoto was pressed on this very question, his answer was not based on naval charts or troop counts. It was based on something he had seen in the hardware stores of Montana, in the fields of the Midwest, and in the stubborn character of the American people. The generals in Tokyo saw America as a target.

5:05

Yamamoto saw it as a fortress. The first and perhaps most shocking revelation he presented to them was not about a new battleship or a secret airbase. It was about the American people themselves. In the Japan of the 1940s, the relationship between the people and the state was one of absolute obedience. After the Meiji Restoration, the government had systematically disarmed the populace.

5:33

The old samurai class had their swords confiscated. Gun ownership was not a right. It was a rare privilege granted only by the state. The army was the only entity with real firepower. This was the lens through which the Japanese generals saw the world. An army fights an army. The civilians, the heimin, simply bow to their new masters.

5:58

Yamamoto had to shatter this illusion. He explained to a room of bewildered commanders what he had witnessed in America. He told them that in the United States, weapons were not just for soldiers. He had seen hardware stores in tiny rural towns that sold rifles and shotguns stacked next to hammers and nails.

6:19

He had seen sporting goods stores where any man could walk in and purchase a firearm with ammunition. He described a culture where fathers taught their sons to hunt, where marksmanship was a point of pride, a tradition passed down from a frontier heritage that was, at the time, only a generation or two removed.

6:41

He wasn’t just talking about a few thousand hobbyists. The intelligence estimates, while difficult to confirm precisely, were staggering. In a nation of 130 million people, there were believed to be around 50 million firearms already in civilian hands. This was a concept the High Command could barely process.

7:03

“So what?” One general might have argued. “They are not trained soldiers. They are civilians.” Yamamoto’s reply, as history remembers it, was chilling. He is famously quoted as having said, “You cannot invade the mainland United States. There would be a rifle behind every blade of grass.” Think about what that simple sentence implied.

7:29

It wasn’t a military calculation. It was a sociological one. He was painting a picture of an invasion that would be unlike any in human history. It wouldn’t be an army fighting an army for control of a capital city. It would be an army fighting an entire populace. Every farmhouse would become a sniper’s nest, every town, a stronghold, every highway, a potential ambush.

7:59

The Japanese soldier trained for decisive battles on open fields or in jungle warfare, would be thrust into a 3000 mile long meat grinder. They would not be fighting a disciplined army that would surrender when its officers were captured. They would be fighting millions of individuals, farmers, factory workers, mechanics and merchants who believed with religious-like fervor that they had a God-given right to defend their own property and their own lives.

8:32

This was the nightmare in Japanese military doctrine. You broke the enemy’s will to fight, but how could you break the will of 100 million people fighting on their own land, for their own homes? There was no surrender point. We often hear these stories, and they resonate with a sense of national pride, a pride in that Greatest Generation and the spirit that defined them.

8:59

If you believe this kind of history, this deeper look into why the world is the way it is is more important than ever to remember. We’d be honored if you’d take a moment to subscribe. It’s a simple click, but it sends a powerful message that you want more stories just like this one. Stories that matter. But Yamamoto’s warning didn’t end there.

9:26

The rifle behind every blade of grass was only the first layer of an impossible problem. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, the Japanese Imperial Army was willing to pay that price in blood. Let’s say they were prepared to lose millions of men fighting a guerrilla war against the entire American population.

9:48

Now they face the problem that no amount of fighting spirit could solve: mathematics. Yamamoto unrolled the maps. The generals in Tokyo were used to island-hopping to fighting in China, a vast land, but one with ancient, defined territories. They looked at the map of the United States, and the reality of the geography began to sink in.

10:12

Japan, as a nation, is a collection of islands roughly the size of California. America was a continent, from the landing beaches in California to the centers of government and industry in the east. An invading army would have to cross nearly 3000 miles. This wasn’t just flat land. First, they would have to fight their way over the Sierra Nevada mountains, a massive granite wall.

10:42

Then, after crossing the deserts of Nevada and Utah, they would face the Rocky Mountains, one of the most formidable mountain ranges on the planet. Even if they made it past those natural fortresses, they would then emerge onto the Great Plains, a vast open expanse stretching for a thousand miles. This was a logistical death trap.

11:08

An army moves on its stomach, and it fights with its supplies. Every single bullet, every single bag of rice, every gallon of gasoline for their tanks and trucks would have to come from Japan. This was the second great impossibility: the tyranny of distance. The Japanese supply line would stretch 5000 miles across the Pacific Ocean.

11:31

This was, by itself, an insane proposal. The United States Navy, shattered at Pearl Harbor, was already rebuilding with a vengeance. American submarines would hunt these supply convoys relentlessly. The journey would take weeks, and every ship that made it through would be a miracle. Meanwhile, what about the Americans? Yamamoto had seen their internal logistics.

11:56

He had seen the web of railroads that crisscrossed the nation. The United States could move an entire army from New York to California in a matter of days, complete with all its tanks, artillery and supplies. Japan’s rail system was tiny and fragmented by comparison, and an invading Japanese army would be stranded.

12:17

They would be an island of troops in a sea of hostile territory. They would be cut off, starved and hunted. Every mile they advanced inland would stretch their non-existent supply lines thinner, while the Americans would only get stronger, drawing on the vast, untouched resources of their own continent, an invasion force would not be able to live off the land.

12:40

The land itself would be fighting them. They would not be able to replenish their supplies. Their supply line would be at the bottom of the Pacific. It was a logistical fantasy. No army in history had ever successfully projected power on such a scale against such a well-defended and geographically massive opponent.

13:01

And even this, the geography and the logistics, was not the giant Yamamoto truly feared, the true giant. The one he had seen in the roaring fires of Detroit and Pittsburgh was the one thing Japan could never hope to match. The problem wasn’t just that America was big. The problem was what America did. Yamamoto had to explain to the High Command that their entire premise for the war was flawed.

13:28

They believed they could cripple America by sinking its fleet. But Yamamoto knew that America’s true power was not in its fleet-in-being, but in its capacity to build a new one and then build another one after that. This was the third and most terrifying impossibility: the Arsenal of Democracy. Let’s put this in perspective with numbers, the kind of hard numbers that would have kept Yamamoto awake at night.

13:56

In 1941, as Japan prepared for war, their industrial capacity was a fraction of America’s. Take steel, the very backbone of any modern war machine. The United States in 1941 produced about half of the world’s steel. Japan’s total output was about 10% of America’s. Or consider oil, the lifeblood of tanks, planes, and ships.

14:23

The United States was the world’s largest producer, drawing over 60% of the world’s entire supply from its own wells in Texas, Oklahoma, and California. Japan, by contrast, had almost no domestic oil. They were completely dependent on imports. The very imports America had just cut off, which is what had forced their hand to attack in the first place.

14:49

The Japanese High Command knew these numbers, but they didn’t understand them. They believed their superior spirit could overcome a deficit in material. Yamamoto knew this was nonsense. War, he understood, is ultimately a battle of production, of logistics, of attrition. And in that battle, Japan had already lost.

15:12

He had seen the automobile factories in Detroit. He told his fellow officers, with no exaggeration, that the American auto industry could, by itself, out-produce the entire war-making capacity of the Third Reich. And he was right. When America turned on the switch, the results were beyond comprehension. The Ford Motor Company, which had perfected the assembly line, built a new factory at Willow Run.

15:41

At its peak that single factory was producing a B-24 Liberator bomber every single hour. Think about that. A four-engine heavy bomber, one of the most complex machines of the age, rolling off the line every 60 minutes, 24 hours a day. Japan celebrated the construction of a new aircraft carrier as a national triumph that took years.

16:09

American shipyards, like the ones run by Henry Kaiser, were applying assembly-line techniques to ships. They were building Liberty cargo ships in a matter of weeks. Then they got it down to days. One ship, the SS Robert E. Peary, was built from the first keel plate to launching in just four days and 15 hours. This was the giant.

16:34

The sleeping giant wasn’t just the American military. It was the American factory worker, the engineer, the farmer. It was a system that could pour out a flood of steel, aluminum and oil, creating a wave of tanks, planes and ships that would be simply unstoppable. Yamamoto’s plan for Pearl Harbor was never to win a long war.

16:57

It was a desperate gamble. He told the High Command that he could run wild for six months or a year. But after that, he had utterly no confidence in victory. He was hoping to inflict a wound so painful, so sudden, that the soft Americans would simply give up. And this led to his fourth, and perhaps most profound realization.

17:21

The final fatal miscalculation made by the generals in Tokyo. They believed the American spirit was weak. Yamamoto, the Harvard man, the student of history, knew they were dangerously wrong. This was the fourth impossibility: underestimating the American character. The Japanese generals, particularly those in the Army, were products of the rigid, feudal and emperor-worshiping Bushido code.

17:51

To them, the highest honor was to die for the Emperor. Surrender was the ultimate shame. They looked at America, a loud, messy, democratic nation where people argued with their government, where individuals were celebrated, and they saw weakness. They saw a lack of cohesion, a lack of spiritual purity. Yamamoto had seen something entirely different.

18:17

He had studied American history. He knew about the Revolutionary War, where a ragtag army of farmers and merchants, fighting for a radical idea of liberty, had defeated the greatest military power on Earth: the British Empire. He knew about the American Civil War, a conflict that had cost more American lives than almost all their other wars combined, fought with a brutal ferocity over the very definition of their nation.

18:48

Yamamoto understood that Americans were not motivated by obedience to a god-emperor. They were motivated by something the High Command couldn’t grasp: individualism. The “Don’t Tread on Me” spirit. The deep, stubborn belief in personal independence and the defense of one’s own home. This, he warned, made them the most unpredictable and dangerous of enemies.

19:13

A professional army like their own follows orders. It attacks when told. It retreats when commanded. But a nation of armed civilians, fighting on their home soil, they don’t follow orders from a distant general. They fight because someone is on their land. They fight for their family, their farm, their town. There is no negotiating.

19:37

There is no single breaking point in the Japanese model of war. You capture the capital. You take Tokyo. The Emperor surrenders. The war is over. But in America, what would you capture if you captured Washington, D.C.? The government would simply move to Chicago. If you captured Chicago, they’d move to Denver.

20:00

Every single state, every single county would continue to resist. The war would be endless. So when the generals asked Yamamoto for his final assessment, he laid out the facts: to invade the United States, Japan would need to cross 5000 miles of ocean, hunted by submarines, to land on a hostile continent. There they would be met on the beaches by not just an army, but by millions of armed citizens with better marksmanship than many of their own soldiers.

20:35

If they survived that, they would have to fight their way across 3000 miles of brutal, unforgiving terrain, including two of the world’s largest mountain ranges. Their supply lines would be non-existent. And all the while, the American Arsenal of Democracy, a manufacturing behemoth that dwarfed their own, would be churning out an endless supply of new tanks, new planes and new ships, arming a populace that was united not by obedience, but by a terrible resolve to never, ever be conquered.

21:12

The room fell silent. The “Victory Disease” was cured. The plan to invade America was quietly shelved, not just as difficult, but as impossible. It’s a spirit that many of us still feel today, a connection to that generation’s grit. It’s a complex topic, and we’re curious to hear your perspective. What part of that American character do you think was the most decisive factor? Was it the independent spirit, the industrial toughness, or something else entirely? Please take a moment and let us know in the comments below.

21:50

We truly value the wisdom and experience our viewers bring, and we read as many comments as we can. Now, this entire story, this grand strategic dilemma has a fascinating and dark mirror image. Because the Japanese High Command had correctly identified all the reasons why invading America was impossible. But they failed to apply that same logic to themselves.

22:18

While they knew they could never conquer America, they held an ironclad belief that America could never conquer them. This brings us to the final, chilling chapter of this story: the invasion that was planned. As the tide of the war turned, as the sleeping giant woke and began its relentless march across the Pacific, the United States faced the very question Japan had shrunk from: what would it take to invade the Japanese homeland? The plan was codenamed Operation Downfall.

22:55

It was scheduled for late 1945 and 1946, and it was, in every sense, the Japanese nightmare in reverse, but with one terrible difference. The American plan called for the largest amphibious assault in human history, far exceeding D-Day in scale. It would involve over a million and a half Allied troops. The first landing, Operation Olympic, would hit the southern island of Kyushu.

23:24

The second, Operation Coronet, would strike near Tokyo itself. The American planners, men like General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz, began to run the numbers. They looked at the geography of Japan. They looked at the fanatical resistance they had faced on islands like Iwo Jima and Okinawa, where Japanese soldiers and even civilians fought to the last man, often taking their own lives rather than surrendering.

23:53

And then they looked at what the Japanese High Command was planning. The Japanese defense plan was called Ketsugo, or “Decisive Operation.” It was, in essence, a plan for national suicide, having failed to stop the American war machine at sea, the High Command decided to stake everything on a final, apocalyptic battle on the beaches of their homeland.

24:17

But this time, they wouldn’t just be using their army. They were preparing to enact the very rifle behind every blade of grass strategy that Yamamoto had feared in America. The Japanese government began to mobilize the entire population. They were dissolving schools to put children to work in factories. They were training civilians, women, old men and boys, not with rifles because they had none to spare, but with bamboo spears, with kitchen knives, with anything that could be used as a weapon.

24:52

They were forming “Patriotic Citizens Fighting Corps.” The plan was simple. When the first American soldiers set foot on the beach, every single man, woman and child in Japan would hurl themselves at the invaders in a final suicidal wave. They were building thousands of kamikaze planes and explosive motorboats designed not to win the battle, but simply to inflict such a staggering number of casualties that the soft Americans would finally lose their nerve.

25:26

This was the ultimate tragic irony. The Japanese leaders who had deemed an invasion of America impossible because of its armed, stubborn populace, were now banking their entire survival on becoming that very thing. When American planners saw this, their casualty estimates were beyond anything the world had ever seen.

25:50

They projected that the United States alone would suffer 400,000 to over 1 million casualties in the invasion of Japan, with at least 100,000 to 500,000 deaths. Japanese casualties, they estimated, would be in the tens of millions. The entire nation would be destroyed. This was the context in which President Harry S.

26:15

Truman, who had just taken office after Roosevelt’s death, was presented with a choice. On one hand, Operation Downfall, a path that would lead to the deaths of millions, including a million of his own men. On the other hand, a new terrible weapon, a secret project that had just been successfully tested in the New Mexico desert.

26:39

The atomic bomb. The decision to use the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki remains one of the most debated and painful moments in modern history. But to understand it, we must understand the alternative. The alternative was Operation Downfall, an invasion that would have made every other battle in the war look like a skirmish.

27:04

The Japanese High Command, by embracing the very porcupine strategy they so feared, had inadvertently made the cost of a conventional invasion so unthinkably high that it forced the unthinkable weapon to become a reality. In the end, Yamamoto was right about everything. He was right about the sleeping giant.

27:28

He was right about the terrible resolve. And he was right that an invasion of a determined, armed and vast nation was a form of military suicide. His wisdom was in seeing the truth when everyone else was blinded by victory. The tragedy is that his own nation, in its final, desperate moments, was forced to prove his theory correct.

27:52

The legacy of this story is not a simple one. It’s a complex lesson in humility, in the dangers of underestimating an opponent, and in the profound, often terrifying power of a people united in the defense of their homeland. It’s a reminder that the greatest strength of a nation is not always found in its soldiers or its ships, but in its factories, its geography, and in the unshakeable character of its people.

News

Dylan Dreyer shocked the entire TODAY studio with a revelation so unexpected it stopped the show cold — and left Craig Melvin frozen in disbelief. What began as a routine segment quickly spiraled into a moment no one on set saw coming, triggering whispers, stunned silence, and a backstage scramble to understand what had just happened. Check the comments for the full story.

Dylan Dreyer’s Startling Live Revelation Brings TODAY Studio to a Standstill — Craig Melvin Left Speechless as Chaos Erupts Behind…

Dylan Dreyer’s new role on TODAY has officially been confirmed — but what should be a celebratory moment is now causing shockwaves behind the scenes. A source claims her promotion may trigger a drastic shake-up, with one longtime host allegedly at risk of being axed as the show restructures its lineup. Tensions are rising, and nothing feels guaranteed anymore. Check the comments for the full story.

OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENT: Dylan Dreyer Takes on Powerful New Role on TODAY — Insider Claims a Co-Host May Be Facing a…

Jenna Bush Hager just revealed the shocking moment NBC asked her to change a single word on live TV — a word she believed would erase her voice, her style, and everything she’d built. What followed wasn’t loud, but it was powerful: a quiet rebellion, a personal stand, and a turning point she never saw coming. Her behind-the-scenes confession finally shows fans the strength beneath her polished smile.

Jenna Bush Hager Just Revealed the Shocking Moment NBC Asked Her to Change a Single Word on Live TV —…

The SEAL Admiral Asked Her Call Sign as a Joke — Then ‘Night Fox’ Turned Command Into Silence

The SEAL Admiral Asked Her Call Sign as a Joke — Then ‘Night Fox’ Turned Command Into Silence The sharp…

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her She was mocked…

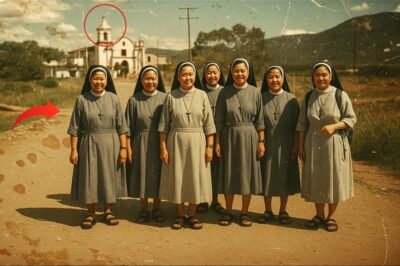

7 Nuns Disappeared During Pilgrimage – 24 Years Later, The Truth Shocks Everyone- Part 1

7 Nuns Disappeared During Pilgrimage – 24 Years Later, The Truth Shocks Everyone- Part 1 In May 2001, seven Benedictine…

End of content

No more pages to load