Every Son in the Winstead Family Spoke a Language No One Could Identify

There’s a photograph that still exists. You won’t find it in any museum. It sits in a safety deposit box in eastern Kentucky, held by a family that refuses to speak its name aloud. The image shows seven boys standing in front of a white farmhouse, their faces solemn, their eyes fixed on something beyond the camera’s frame.

They range in age from 4 to 19. Every single one of them is a winstead, and every single one of them spoke a language that shouldn’t exist. The year was 1947. The place was Harrow County, a stretch of Appalachin farmland so isolated that mail came once a week and doctors didn’t. When state officials finally arrived at the Winstead property that autumn, they found something that would haunt them for the rest of their lives.

Not evidence of abuse, not signs of neglect, but seven brothers who communicated in a tongue that had no root in English, no connection to any known language on earth, and no explanation that anyone could provide. The boys understood English perfectly. They simply refused to speak it to each other.

And when pressed by authorities to explain where their language came from, the oldest boy, Samuel, said something that was recorded in the county report, but never made public. our father taught us before he forgot. Hello everyone. Before we start, make sure to like and subscribe to the channel and leave a comment with where you’re from and what time you’re watching.

That way, YouTube will keep showing you stories just like this one. What you’re about to hear is not folklore. It’s not an urban legend whispered around campfires. This is a documented case that involved state linguists, child psychologists, and eventually federal investigators. The Winstead brothers became the subject of academic papers that were later withdrawn, interviews that were sealed, and a single audio recording that was destroyed in a fire that authorities ruled accidental, but that no one in Harrow County believed was anything but

deliberate. The family still lives in Kentucky. They still don’t give interviews. And according to the one journalist who managed to speak with a surviving relative in 2008, the language never fully disappeared. It just went underground. This is the story of the Winstead brothers and the question that still has no answer.

Who taught them to speak? The Winstead family came to the attention of authorities because of a school teacher named Margaret Holloway. In September of 1947, she was assigned to the one room schoolhouse that served the children of Harrow County’s most remote families. On her first day, three Winstead boys arrived together.

Samuel, age 14, Thomas, age 11, and Joseph, age 8. They sat in the back row. They didn’t cause trouble. But within an hour, Margaret noticed something that made her skin crawl. The boys were whispering to each other. Not in English, not in any language she recognized. The sounds were guttural, rhythmic, almost melodic in places, consonants that clicked at the back of the throat, vowels that bent in ways that didn’t match the Appalachin draw every other child in that room carried like a birthright.

She approached them during recess, asked them what language they were speaking. Samuel looked at her with an expression she would later describe as pity. He said in perfect English, “It’s ours, ma’am. Just ours.” Margaret let it go. For three days, she let it go. But the whispering didn’t stop. And worse, it began to spread.

By the end of the first week, she noticed two younger Winstead boys, ages 6 and four, sitting outside the schoolhouse during lunch, speaking the same impossible language. They had never attended school before. They weren’t old enough, but somehow they had come with their brothers that day, and no one had questioned it.

3:46

When Margaret asked the older boys why their younger siblings were there, Thomas answered flatly. They wanted to listen. She reported it to the county superintendent on a Friday afternoon. Told him she believed the Winstead boys were speaking some kind of invented dialect, possibly as a form of rebellion or isolation.

4:04

The superintendent, a man named Charles Dillard, dismissed her concerns. He told her Appalachin families were strange, insular, and that children often created games that adults didn’t understand. He told her to stop wasting his time. But Margaret Holloway didn’t stop. She did something that would change everything.

4:22

She brought a tape recorder to school the following Monday. A realtoreal machine borrowed from the county library. And during recess, while the Winstead boys sat beneath an oak tree, speaking to each other in low, careful tones, she recorded them. That recording was played for Charles Dillard 3 days later. He listened in silence.

4:42

Then he called the state police. Not because he thought the boys were in danger, but because he didn’t recognize a single word, they said, and neither did anyone else. Within two weeks, the Winstead farm was swarming with officials. Not in a violent way, not like a raid. It was quiet, methodical, the kind of intrusion that happens when the state realizes it has no idea what it’s looking at.

5:07

A social worker named Patricia Vance arrived first, accompanied by a county deputy and a linguist from the University of Kentucky named Dr. Leon Marsh. They drove up the long dirt path to the Winstead property on a gray October morning, and what they found was a family that had been expecting them. The father, Clarence Winstead, met them at the door.

5:30

He was 46 years old, rail thin, with hands that trembled when he shook Dr. Marsh’s hand. His wife, Norah, stood behind him, silent, her face drained of color. Inside the house were the seven boys. All of them present, all of them seated in the front room as if they’d been arranged for a photograph. The youngest, a boy named Daniel, age four, sat on the floor at his mother’s feet.

5:53

He didn’t look up when the officials entered. None of them did. Patricia Vance would later write in her report that the boys seemed preinaturely calm, as though they had rehearsed this moment many times before. Dr. Marsh asked Clarence directly. What language were his sons speaking? Clarence said he didn’t know. Dr.

6:12

Marsh asked if the boys had been taught a foreign language by a relative, a hired hand, a traveling preacher. Clarence said no. Dr. Marsh asked if the family had any European ancestry, any connection to immigrant communities, anything that might explain a linguistic anomaly of this scale. Clarence Winstead looked at him and said, “We’ve been in Kentucky since 1792.

6:35

We don’t know anything but English.” Then Dr. Marsh did something unusual. He turned to Samuel, the oldest boy, and asked him in front of his parents to speak the language. Samuel didn’t hesitate. He stood, looked directly at the linguist, and spoke for 30 seconds in a fluid, unbroken stream of sounds that Doc Marsh would later describe as structurally consistent, phonetically complex, and utterly unrecognizable.

7:01

When Samuel finished, Dr. Marsh asked him what he had just said. Samuel translated without emotion. I told you that you won’t understand it because it isn’t yours to understand. The room went silent. Patricia Vance glanced at the other boys. Not one of them reacted. Not one of them smiled or fidgeted or looked surprised.

7:22

They simply sat there watching. Doctor Marsh asked Samuel where he learned the language. Samuel said, “Our father taught us.” Clarence Winstead’s face went white. He stood abruptly and said, “I never taught them a damn thing.” Doctor Marsh turned back to Samuel and asked, “Then who did?” And Samuel Winstead, 14 years old, looked at his father with something close to sadness and said, “You did before you forgot.

7:50

” Clarence Winstead was questioned alone 3 days later. He sat in a windowless room at the county administrative building, a cup of cold coffee in front of him, his hands folded on the table. Patricia Vance and Dr. Marsh were present. A stenographer recorded every word. What Clarence said during that interview was sealed for 60 years.

8:12

It was finally released in 2007 under a Freedom of Information Act request filed by a graduate student researching linguistic isolation in Appalachia. The transcript is 11 pages long. Most of it is Clarence repeating the same thing. He didn’t teach his sons anything. He didn’t know where the language came from. He didn’t understand why they spoke it.

8:32

But on page 8, something shifts. Dr. Marsh asked Clarence if he had ever heard the language before his sons began speaking it. Clarence hesitated. Then he said yes. He said he remembered hearing it once a long time ago when he was a boy. He couldn’t have been more than seven or eight years old. His own father, a man named Eli Winstead, had been sick with fever, delirious, lying in bed and muttering to himself in the dark.

8:59

Clarence said he stood outside his father’s bedroom door and listened. The sounds coming from that room weren’t English. They weren’t anything he recognized. And when his father recovered a week later, Clarence asked him what he’d been saying. Eli looked at his son and told him he didn’t remember. Told him it was just fever talk.

9:17

Told him to never bring it up again. Clarence said he forgot about it or tried to. But years later, when his own sons were born, something started happening. He said he would wake in the middle of the night and hear himself whispering, not in English. in something else. He said it felt like remembering a song he’d never learned.

9:38

He said it terrified him, so he stopped, forced himself to stop. He never spoke those sounds aloud again. But his sons, he said, must have heard him. They must have learned it before he buried it. Dr. Marsh asked him if he could still speak the language. Clarence said no. He said it was gone, locked away. Dr.

9:58

Marsh asked him if he wanted to remember and Clarence Winstead, 46 years old, father of seven, looked at the linguist with tears in his eyes and said, “God, no. I don’t ever want to remember.” The interview ended shortly after. Clarence was released. No charges were filed. No further action was taken against the family. But Dr.

10:17

Marsh didn’t stop. He spent the next 6 months studying the Winstead boys. He recorded over 40 hours of their speech. He analyzed syntax, phonetics, grammar. He consulted with colleagues at Harvard, Princeton, and the Sorbon. And every single one of them came to the same conclusion. The language was real. It had structure. It had rules.

10:38

It wasn’t random. It wasn’t invented by children playing a game. It was old, and no one knew where it came from. Dr. Leon Marsh kept meticulous notes. His archive, now housed at the University of Kucky’s Special Collections Library, contains transcripts, audio logs, and handwritten observations spanning from October 1947 to April 1948.

11:02

What he documented during those months has never been fully explained. The language the Winstead Boys spoke wasn’t just consistent, it was evolving. Between the first recording in October and the last in April, Dr. Marsh noted over 300 new words, 14 grammatical shifts, and the emergence of what he called ritual phrases that the boys used only in specific contexts.

11:27

When he asked Samuel what these phrases meant, the boy said they were for remembering. When Dr. Marsh asked what they were supposed to remember, Samuel wouldn’t answer. But the most disturbing discovery came in January of 1948. Dr. Marsh was reviewing recordings from separate interviews he’d conducted with each brother individually.

11:47

He’d asked them all the same question. Describe your earliest memory. All seven boys answered in the language. And when Dr. Marsh had their responses translated by Samuel weeks later, he realized something that made him stop sleeping well. Every single boy described the same memory. Not similar memories, the exact same one.

12:08

They spoke of standing in a forest at night, of hearing a voice calling to them from the trees, of following that voice until they reached a clearing where their father stood, younger than they’d ever seen him, speaking words they didn’t yet understand, but knew they had to learn. Samuel said the memory felt more real than anything that had happened since.

12:26

Thomas said he saw it every time he closed his eyes. Joseph, the 8-year-old, said it wasn’t a memory at all. He said it was still happening. Dr. Marsh brought this to the attention of the state psychologist assigned to the case, a woman named Dr. Elellanar Finch. She interviewed the boys herself separately on different days without telling them what she was looking for.

12:47

And they all told her the same thing, the same forest, the same voice, the same impossible memory of a father who looked 30 years younger teaching them a language that shouldn’t exist. Doctor Finch wrote in her report that the boys showed no signs of delusion, no signs of coaching, no signs of collaboration. She wrote that they believed what they were saying with a conviction that unnerved her.

13:11

She recommended the family be monitored but not separated. She said removing the boys from their home might cause psychological harm. What she didn’t write, but told a colleague years later was that she believed the boys weren’t lying. She believed they had all seen the same thing, and she didn’t know how that was possible.

13:29

If you’re still watching, you’re already braver than most. Tell us in the comments, what would you have done if this was your bloodline? By March of 1948, Dr. Marsh had compiled enough data to publish a paper. He titled it, “A case study in Isolated Linguistic Development. He submitted it to three academic journals. All three accepted it, but before it could be printed, he received a visit from two men in dark suits who identified themselves as federal investigators.

13:59

They didn’t say which agency they were from. They told Dr. Marsh his research was being classified for reasons of national security. They confiscated his recordings. They took his notes. They told him he was never to speak publicly about the Winstead family again. Dr. Marsh protested. He demanded an explanation.

14:19

And one of the men said something that Dr. Marsh repeated to his wife that night and that she shared with a reporter 40 years later. You’re not the first to find a family like this. And every time we do, the same thing happens. The father doesn’t remember. The sons do, and we still don’t know why.

14:39

On the night of May 14th, 1948, a fire broke out in the basement of the Harrow County Administrative Building. It started just after midnight. By the time the volunteer fire department arrived, the entire lower level was engulfed. No one was hurt. The building was empty, but everything stored in that basement was destroyed. That included all physical records related to the Winstead case, the original tape recording made by Margaret Holay.

15:03

The transcripts of Clarence Winstead’s interview, the psychological evaluations, the copies of Dr. Marsh’s confiscated notes that had been held by the county, all of it turned to ash. The fire marshall ruled it an electrical fault, a frayed wire in the old building’s wiring system, but there were problems with that explanation.

15:22

The building had been inspected just two months prior, and passed with no issues. The fire started in a specific section of the basement where the Windstead files were stored, not near any electrical panels. And 3 days before the fire, a county clerk named Thomas Ritter told his wife he’d been asked by two men in suits to show them where certain files were kept.

15:44

He described the men as polite but cold. He said they didn’t give names. He said they spent 20 minutes looking at boxes in the basement and then left without taking anything. Thomas Ritter died of a heart attack in 1953. He was 34 years old. Margaret Holloway, the school teacher who started it all, left Harrow County in June of 1948.

16:06

She took a position in Ohio and never returned. In a letter to a friend written in 1961, she said she still thought about the Winstead Boys. She said she still heard their voices sometimes late at night, whispering in a language she’d only heard once but could never forget. She said she was glad the recordings were gone. She said some things weren’t meant to be preserved.

16:25

Margaret Holloway died in 1987. She never married. She never taught again after leaving Ohio in 1965. In her personal effects, her niece found a small notebook filled with strange symbols, phonetic notations, attempts to recreate the sounds she’d heard those boys make nearly 40 years earlier. The notebook was donated to a local historical society.

16:50

It was lost in a flood in 2003. Dr. Leon Marsh never published another paper on linguistics. He continued teaching at the University of Kentucky until his retirement in 1976, but colleagues said he became withdrawn, obsessive, paranoid. He claimed his office had been broken into multiple times, though nothing was ever reported stolen.

17:12

He told a graduate assistant in 1972 that he’d kept one thing the federal agents didn’t know about. a single reel of tape he’d hidden in his home, a recording of Samuel Winstead speaking for 10 uninterrupted minutes in the language. He said he listened to it once a year. He said he still couldn’t understand a word, but that he felt something every time he heard it, a pull, a recognition, like his own blood was trying to remember something it had forgotten. Dr.

17:39

Marsh did in 1981. His house was emptied by his daughter. She found no tape. She found no recordings. She found a locked drawer in his desk that had been pried open. Whatever had been inside was gone. The Winstead family never left Harrow County. The seven brothers grew up. They married. They had children of their own.

18:00

And according to every public record, they lived quiet, unremarkable lives. Samuel became a carpenter. Thomas worked at a lumberm mill. Joseph ran a small hardware store in town until he retired in 1992. They attended church. They paid their taxes. They never gave interviews. And to anyone who asked, they said they didn’t remember speaking any language but English.

18:25

But there are stories, whispers that never quite died. In 1976, a journalist from Louisville drove to Harrow County to investigate the Winstead case after reading a brief mention of it in a university archive. He spoke to several towns people. Most refused to talk. But one older woman, who’d been a neighbor of the Winsteads in the 50s, told him something strange.

18:47

She said she used to hear the boys at night, even as grown men, standing outside together and speaking in low voices. She said it didn’t sound like English. She said it didn’t sound like anything from this world. When the journalist tried to contact the Winstead brothers directly, he received a visit from a local sheriff who told him he wasn’t welcome in Harrow County.

19:07

He left that same day. His article was never published. In 2008, a genealogologist researching Appalachian family lines managed to contact a grandson of Thomas Winstead. The grandson, who asked not to be named, agreed to a brief phone conversation. He said his grandfather never spoke about the language, never acknowledged it.

19:30

But he said that once, when he was 12 years old, he walked into his grandfather’s workshed and found him standing alone, whispering to himself. The boy froze. His grandfather didn’t notice him at first, and the sounds coming out of that old man’s mouth were nothing the boy had ever heard. Guttural, rhythmic, ancient. When Thomas finally saw his grandson standing there, he stopped mid-sentence.

19:53

He looked at the boy with an expression of pure fear. And then he said in English, “Don’t ever repeat what you just heard, not to anyone, not even to yourself.” The grandson said he never did, but he said he still remembered the sounds. He said sometimes late at night he caught himself whispering them and he had no idea why.

20:14

There’s a theory that’s never been proven but never quite gone away. It suggests that the Winstead language wasn’t invented. It wasn’t learned from a book or a traveler or a forgotten dialect. It was inherited, passed down not through teaching, but through blood, through something deeper than memory. Dr. Marsh believed it. Dr. Finch suspected it.

20:34

And if you read between the lines of the federal investigators confiscated reports, the ones that were partially declassified in 2012, you’ll find references to genetic linguistic memory and hereditary speech patterns with no environmental trigger. You’ll find mentions of other families, other cases, other children who spoke languages no one recognized.

20:56

and you’ll find a single note written in the margin of one report in handwriting that was never identified. The fathers always forget, the sons always remember. We still don’t know which one is the curse. The last surviving Winstead brother, Daniel, the youngest, died in 2019. He was 76 years old.

21:17

He left behind three daughters and 12 grandchildren. At his funeral, one of his daughters gave a eulogy. She spoke about her father’s kindness, his quiet strength, his love for his family. And at the very end, she said something that made several people in attendance go still. She said that the night before he died, her father had called her to his bedside.

21:37

He was struggling to breathe, struggling to speak, but he grabbed her hand and whispered something to her, a string of sounds she didn’t understand. She asked him what it meant. And Daniel Winstead with his last bit of strength looked at his daughter and said, “It means we’re still here.” The language of the Winstead family was never translated.

21:56

It was never decoded. It exists now only in fragments, in memories that fade, in recordings that were destroyed, in bloodlines that continue. And somewhere in eastern Kentucky, there are children being born who may one day wake up speaking words their parents never taught them. Words that have no origin, no history, no explanation, just a voice passed down through generations, whispering in the dark, reminding them of something they were never supposed to forget.

22:28

If you made it this far, thank you for watching. Leave a comment and let us know what you think really happened to the Winstead family. And remember to subscribe because stories like this are just the beginning. There are more families, more languages, more secrets buried in American soil. And we’re going to find every single one of

News

Dylan Dreyer shocked the entire TODAY studio with a revelation so unexpected it stopped the show cold — and left Craig Melvin frozen in disbelief. What began as a routine segment quickly spiraled into a moment no one on set saw coming, triggering whispers, stunned silence, and a backstage scramble to understand what had just happened. Check the comments for the full story.

Dylan Dreyer’s Startling Live Revelation Brings TODAY Studio to a Standstill — Craig Melvin Left Speechless as Chaos Erupts Behind…

Dylan Dreyer’s new role on TODAY has officially been confirmed — but what should be a celebratory moment is now causing shockwaves behind the scenes. A source claims her promotion may trigger a drastic shake-up, with one longtime host allegedly at risk of being axed as the show restructures its lineup. Tensions are rising, and nothing feels guaranteed anymore. Check the comments for the full story.

OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENT: Dylan Dreyer Takes on Powerful New Role on TODAY — Insider Claims a Co-Host May Be Facing a…

Jenna Bush Hager just revealed the shocking moment NBC asked her to change a single word on live TV — a word she believed would erase her voice, her style, and everything she’d built. What followed wasn’t loud, but it was powerful: a quiet rebellion, a personal stand, and a turning point she never saw coming. Her behind-the-scenes confession finally shows fans the strength beneath her polished smile.

Jenna Bush Hager Just Revealed the Shocking Moment NBC Asked Her to Change a Single Word on Live TV —…

The SEAL Admiral Asked Her Call Sign as a Joke — Then ‘Night Fox’ Turned Command Into Silence

The SEAL Admiral Asked Her Call Sign as a Joke — Then ‘Night Fox’ Turned Command Into Silence The sharp…

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her She was mocked…

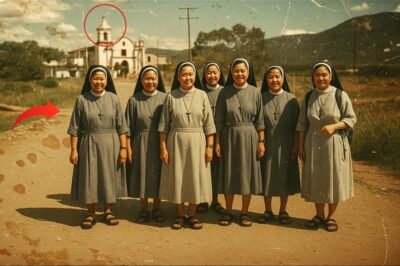

7 Nuns Disappeared During Pilgrimage – 24 Years Later, The Truth Shocks Everyone- Part 1

7 Nuns Disappeared During Pilgrimage – 24 Years Later, The Truth Shocks Everyone- Part 1 In May 2001, seven Benedictine…

End of content

No more pages to load