A historical scandal: 47 children discovered in the Schneider family’s cellar (1834)

In the spring of 1834, somewhere in the rolling hills of Thuringia, a discovery was made that would forever change how we understand the depths of human cruelty. Forty-seven children, aged six to sixteen, were found chained in a cellar beneath a house that, from the outside, appeared to be an ordinary farmhouse.

The children were all very different, spoke different languages, and, when questioned through tears, could only whisper one name: Mother Schneider. The report by the local magistrate, which remained hidden in the archives of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar for over a century, described scenes so harrowing that three of the investigating officers resigned within a week.

What made this case truly terrifying was not only the horror of what was discovered, but the chilling realization that Konstanze Schneider had carried out her twisted work undetected for more than two decades. The children called her Mother. But the truth behind this title would prove far darker than anyone could have imagined.

Before we continue with the story of the Schneider family and their unspeakable secrets, I have something important to ask you. This story is not for everyone, but only for the bravest souls who dare to confront the darkest chapters of Germany’s past. If you have read this far, you are not like most people. You understand that some truths are too horrific to ignore, no matter how disturbing they may be.

The question that tormented investigators back then, and that continues to haunt historians today, is how such a large-scale operation could have remained undetected for so long in a tightly knit rural community. Thuringia in 1834 was a land between two worlds.

The old feudal structures still shaped daily life, while the first signs of industrial change were emerging from the west and north. In this setting, the small village of Mühlgrund, with perhaps 50 families scattered across the wooded hills and fields, represented a typical rural settlement in Central Germany at that time.

Most residents lived by farming grain, raising goats or pigs, and trading goods in the general store run by the couple Heller. Social gatherings usually took place in the one-room village school, which also served as a meeting house. The Schneiders’ property lay on the edge of this community.

A modest two-story timber-framed house surrounded by almost 200 acres of fertile farmland. To travelers on the country road connecting Mühlgrund to Weimer, the farmstead appeared quite inconspicuous. The house itself, built in the traditional Thuringian style, featured whitewashed timber framing with dark beams and a small flower garden in front of the entrance.

A red barn stood six paces behind the house, complemented by a chicken coop and a smokehouse, completing the familiar picture of a farm. What made the Schneiders’ property unique, however, was not apparent from the street. Ernst Schneider, who had acquired the land in 1809 with money from his father’s inheritance, had gone to considerable lengths to expand the house’s cellar.

While most houses in Thuringia at that time had only simple storage cellars, the Schneiders’ cellar extended far beyond the house’s footprint. Local craftsmen recalled being hired for various excavation jobs in the 1810s and 1820s. Yet no one had ever seen the finished work.

Schneider paid well and in cash, but demanded that the workers concentrate on their respective sections rather than overseeing the entire project. Konstanze Schneider, née Müller, had come to Mühlgrund in 1811 as a 22-year-old bride.

Neighbors described her as a beautiful woman with dark hair and an unusually soft voice. She dressed simply but neatly, attended Protestant church services when her health permitted, and cultivated a reputation for charitable work. When asked for contributions to charitable causes, Konstanze always explained that she and Ernst were already caring for several orphaned children from her family in Saxony.

This arrangement, she said, was only temporary until suitable permanent accommodations could be found. This explanation was enough to satisfy the community’s curiosity regarding occasional sightings of children at the tailor’s house.

Mrs. Heller from the general store later reported that she had sometimes seen a child’s face peeking out from the tailor’s cart when Konstanze was there.

Konstanze drove to town to buy supplies. The children never spoke, but Konstanze explained that they were shy, traumatized by the loss of their parents, and needed time to adjust to their new surroundings. Since the village community was familiar with the plight of orphaned children during a time of high mortality rates, they accepted this explanation without question.

Johann Heller, who ran the shop, later recalled that Konstanze Schneider was one of their most reliable customers. Every two weeks, she would appear with a detailed list and enough cash to buy large quantities of basic foodstuffs: rye flour, oats, salt, pork, sauerkraut, and other provisions.

The quantities seemed unusually large for a childless couple. But whenever Johann brought this up, Konstanze reminded him of the supposedly orphaned children. She also bought unusually large quantities of basic medications, explaining that children from impoverished backgrounds often contracted illnesses that needed treatment. The Schneider farm operated according to a schedule that struck some neighbors as odd.

While most families rose at sunrise and worked until dusk, the Schneiders’ farm was often bustling with activity well into the night. Lights burned in the windows of the timber-framed house at unusual hours, and sometimes the sounds of hammering or construction work echoed through the fields.

When questioned seriously, he explained that he was making improvements to accommodate the growing number of children. Dr. Markus Weiß, the itinerant country doctor who served the region around Mühlgrund, later recalled being called to the Schneider farm several times in the 1820s and early 1830s. Each time, the call came that one of the orphaned children was ill and needed medical attention. However, Dr. Weiß was never allowed to examine the children himself.

Instead, Konstanze described the symptoms and requested specific medications. When the doctor insisted on seeing his patients, she explained that the children were too afraid of strangers, too traumatized by their experiences to be examined by an unknown man.

The deception was so convincing that even the local pastor, Samuel Krause, believed in the Schneiders’ charitable work. During his occasional visits, he praised Konstanze and Ernst for their Christian compassion in taking in so many unfortunate children. He offered to help find permanent homes for them. But Konstanze always assured him that she was already corresponding with relatives in Saxony who would eventually take the children in.

This process, she explained, simply required patience and careful planning. No one in the community suspected that Konstanze Schneider had perfected her deception over two decades. The orphaned children were not temporary guests waiting for loving families. They were captives, bought, kidnapped, or torn from their families across multiple regions and held in conditions that would have brought even hardened criminals to tears.

The discovery that would expose the horrific secrets of the Schneider family began with a series of seemingly unrelated incidents in the early months of 1834. February had been unusually harsh, with temperatures remaining well below freezing for weeks.

The relentless cold that gripped Thuringia that winter would prove to be both a blessing and a curse for the 47 children imprisoned beneath the Schneider house. On February 23, 1834, a traveling merchant named Jakob Stern was en route from Weimar to Jena when a fierce blizzard forced him to seek shelter.

The Schneiders’ farm, the nearest building visible from the road, seemed the obvious choice for emergency accommodation. Ernst Schneider, despite his obvious reticence, could hardly refuse hospitality to a stranded traveler in such dangerous weather.

Stern later described the evening as uncomfortably tense. Konstanze Schneider served a simple meal of rye bread and salted meat. But the conversation remained halting and awkward. The Schneiders seemed nervous, constantly glancing at each other and startled by every sound. When Stern asked about the children he had heard lived on the farm, Konstanze explained: “They were all asleep and mustn’t be disturbed.”

“The children,” she said, “were weakened by fever and needed rest.” But what disturbed Stern most was a sound. While lying on a makeshift bed in the Schneiders’ living quarters that night, he heard muffled wine that seemed to rise from the floor. When he mentioned this seriously the next morning, Schneider explained: “It was…”

News

Dylan Dreyer shocked the entire TODAY studio with a revelation so unexpected it stopped the show cold — and left Craig Melvin frozen in disbelief. What began as a routine segment quickly spiraled into a moment no one on set saw coming, triggering whispers, stunned silence, and a backstage scramble to understand what had just happened. Check the comments for the full story.

Dylan Dreyer’s Startling Live Revelation Brings TODAY Studio to a Standstill — Craig Melvin Left Speechless as Chaos Erupts Behind…

Dylan Dreyer’s new role on TODAY has officially been confirmed — but what should be a celebratory moment is now causing shockwaves behind the scenes. A source claims her promotion may trigger a drastic shake-up, with one longtime host allegedly at risk of being axed as the show restructures its lineup. Tensions are rising, and nothing feels guaranteed anymore. Check the comments for the full story.

OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENT: Dylan Dreyer Takes on Powerful New Role on TODAY — Insider Claims a Co-Host May Be Facing a…

Jenna Bush Hager just revealed the shocking moment NBC asked her to change a single word on live TV — a word she believed would erase her voice, her style, and everything she’d built. What followed wasn’t loud, but it was powerful: a quiet rebellion, a personal stand, and a turning point she never saw coming. Her behind-the-scenes confession finally shows fans the strength beneath her polished smile.

Jenna Bush Hager Just Revealed the Shocking Moment NBC Asked Her to Change a Single Word on Live TV —…

The SEAL Admiral Asked Her Call Sign as a Joke — Then ‘Night Fox’ Turned Command Into Silence

The SEAL Admiral Asked Her Call Sign as a Joke — Then ‘Night Fox’ Turned Command Into Silence The sharp…

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her She was mocked…

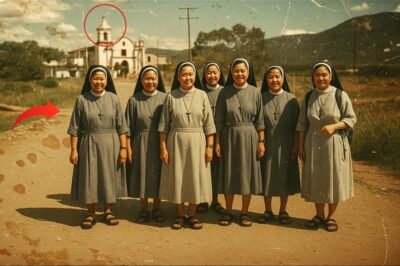

7 Nuns Disappeared During Pilgrimage – 24 Years Later, The Truth Shocks Everyone- Part 1

7 Nuns Disappeared During Pilgrimage – 24 Years Later, The Truth Shocks Everyone- Part 1 In May 2001, seven Benedictine…

End of content

No more pages to load