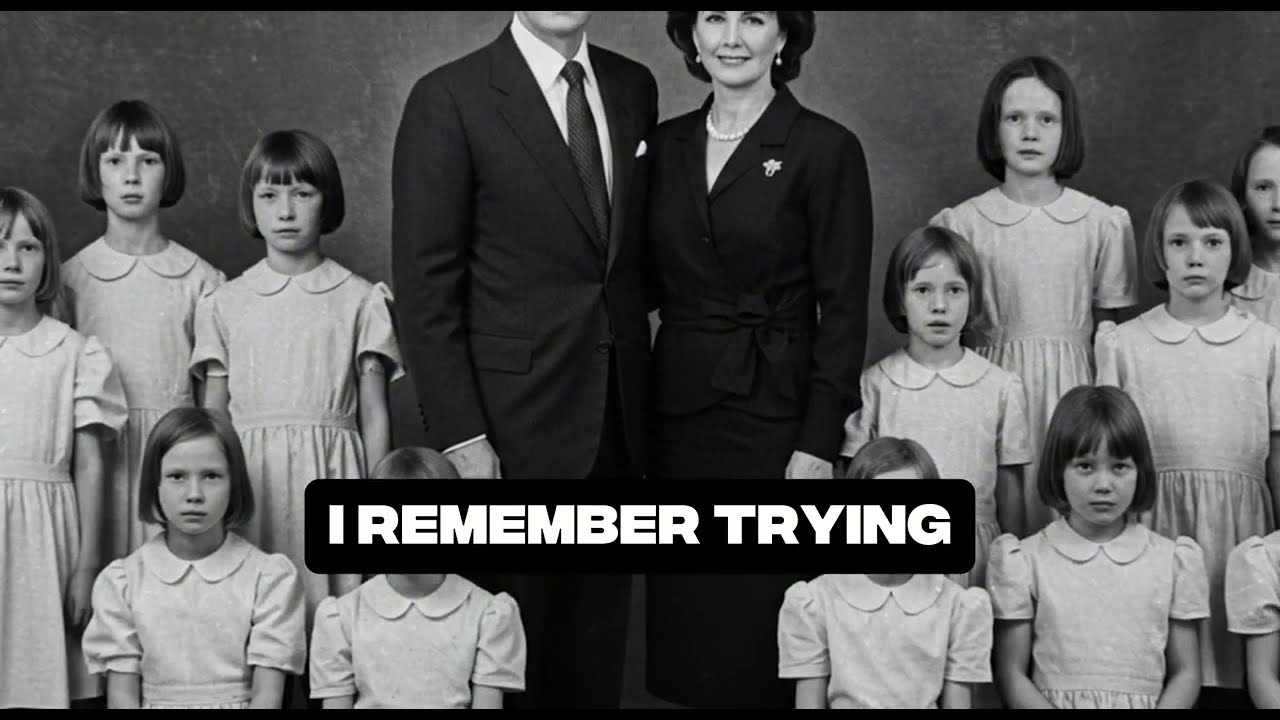

Welcome back to the Ghastly Journal, where we uncover the darkest stories hidden in the shadows of seemingly ordinary lives. Today we dive into a case that will make you question the very foundations of what we call family. This is the Macabra history of the fallings, a couple who adopted 12 children over the span of 15 years, none of whom had birth certificates.

What began as a heartwarming story of generosity quickly unraveled into something far more sinister. Before we begin, remember to subscribe to the Ghastly Journal and turn on notifications so you never miss our weekly descent into the darkest corners of human history. Now, let’s begin. The small town of Milbrook, nestled in the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania, was hardly the kind of place where you’d expect to find a story so disturbing that it would eventually attract the attention of federal investigators.

With a population of just under 3,000 people, Milbrook was the kind of place where everyone knew everyone, where community potlucks and high school football games were the highlights of the social calendar, and where neighbors still brought casserles when someone fell ill.

It was in this idyllic setting that Howard and Margaret Foing made their home in the spring of 1978. The foing residence was a sprawling Victorian mansion on Elm Street, set back from the road and partially hidden by a cops of ancient oak trees. The house had been vacant for nearly a decade before the Foings purchased it. And the locals had begun to call it the haunted house on the hill.

But Howard Falling, a successful investment banker from Pittsburgh, saw potential in the dilapidated structure. He and his wife Margaret, a former pediatric nurse, spent a small fortune renovating the property, transforming it from a crumbling eyesore into the envy of the neighborhood.

They seemed like such a lovely couple, recalls Elaine Winters, who lived across the street from the fallings for nearly 20 years. Howard was always impeccably dressed, even when he was just checking the mail. And Margaret, well, she had this way about her, so poised, so elegant.

They were the kind of people you’d want to invite to dinner, you know, the kind of people who made you feel important just by talking to you. But beneath the veneer of respectability, the fallings harbored secrets that would eventually shock the entire community. According to public records, Howard and Margaret were unable to have biological children of their own.

This was a source of great sorrow for Margaret, who had always dreamed of having a large family. She used to watch the neighborhood children playing from her porch, says Winters. There was something so sad about it, the way she’d just sit there for hours watching them laugh and run around. I remember thinking at the time that she would have made a wonderful mother.

And indeed, it seemed that Margaret would finally get her chance at motherhood when in the summer of 1980, the fallings announced that they had adopted a baby boy whom they named James. The community was thrilled for them. Neighbors organized a surprise baby shower and the local church held a special blessing ceremony for the new family.

James Foing was a beautiful child, brighteyed and quick to smile. And the Foings doted on him obsessively. Margaret wouldn’t let anyone else hold him. Remembers Clara Jenkins who attended the same church as the Foings. Not even at his blessing ceremony.

When the pastor asked to hold him for the blessing, she got this look on her face like a cornered animal. Howard had to whisper something to her before she’d hand him over. And even then, she stood so close to Pastor Williams that she was practically breathing down his neck. In retrospect, this possessiveness might have been the first red flag, but at the time it was easily dismissed as the natural protectiveness of a new mother, especially one who had waited so long to have a child.

Within 2 years, the Foings had adopted a second child, a girl they named Elizabeth. And then in rapid succession came Thomas, Catherine, and William. By 1985, the Fallings had five adopted children, all under the age of six. The speed with which they were able to adopt was unusual, especially given the typically lengthy adoption process in Pennsylvania at that time.

But Howard Falling was wealthy and well-connected, and the couple had an impeccable reputation in the community. They were seen as saviors, says Detective Richard Cooper, who would later lead the investigation into the Foing family. Here was this wealthy couple taking in children who might otherwise have grown up in the system.

Who was going to question that? Who would want to? But there were oddities that, in hindsight, should have raised concerns. None of the Foing children attended public school. Margaret insisted on homeschooling them. The children were rarely seen in town, and when they were, they were never allowed to stray far from their parents’ sides.

They didn’t participate in sports or other extracurricular activities, and they had no friends outside the family. I remember trying to arrange a playd date for my son with James Foing, says former Milbrook resident Patricia Hayes. They were about the same age, and James seemed so lonely. But Margaret always had an excuse.

James was ill or he had too much schoolwork or they were planning a family trip. After a while, I stopped asking. The isolation of the Foing children might have continued indefinitely if not for an accident that occurred in the summer of 1987. 9-year-old Thomas Falling fell from a tree in the family’s backyard and broke his arm. Margaret, despite her background as a nurse, didn’t take him to the hospital.

Instead, she attempted to set the bone herself, resulting in a compound fracture that became infected. It was only when Thomas developed a dangerously high fever that Howard finally overruled his wife and took the boy to the emergency room. Dr. Sarah Chen was the attending physician at Milbrook General Hospital when Thomas was brought in.

The child was in septic shock by the time he arrived, Dr. Chen recalls. We had to perform emergency surgery to save his arm. And even then, there was significant nerve damage. What struck me most, though, was the boy’s reaction. He didn’t cry. Not once during the entire ordeal.

And when I asked him how he’d broken his arm, he looked at his father before answering. It was as if he was waiting for permission to speak. Dr. Chen’s concerns deepened when she asked for Thomas’s medical records and was told that they didn’t exist. According to Howard Falling, all of the children’s records had been lost in a fire at their previous adoption agency. When Dr.

Chen pressed for more information, Howard became agitated and threatened to transfer Thomas to another hospital. That’s when I knew something was wrong, says Dr. Chen. But I had no proof, only suspicions. And in a town like Milbrook, suspicions about a family like the Foings could damage your career. Nevertheless, Dr.

Chen filed a report with child protective services expressing her concerns about potential medical neglect. A caseworker named David Morris was assigned to investigate. Morris visited the Foing home, interviewed the parents, and observed the children. His report filed 3 weeks later, concluded that there was no evidence of abuse or neglect. The children appeared healthy and well cared for.

Morris wrote, “The home environment is clean and safe. Mrs. Falling explained that she initially tried to treat Thomas’s injury herself due to her medical background and a fear of hospitals stemming from her own childhood experiences. While this decision was ill advised, it does not constitute willful neglect. The case was closed and life in Milbrook returned to normal.

The Foings continued to expand their family, adopting three more children between 1988 and 1990, Robert, Anne, and Henry. By now, some in the community were beginning to whisper about the unusual family on Elm Street. How were they able to adopt so many children so quickly? Why were the children so rarely seen in public? And why did they all share the same vacant expression as if something vital had been drained from them? I used to watch them at church, says Jenkins.

Eight children, all sitting in a perfect row, not fidgeting, not whispering, not doing any of the things that normal children do during a long service. They just sat there staring straight ahead. It was unnatural. But if the community had questions, they kept them largely to themselves. The Fings were generous donors to local causes, and Howard sat on the boards of several influential charities.

They were, by all outward appearances, model citizens. Then in the winter of 1992, a new family moved to Milbrook. Michael and Susan Fletcher, along with their teenage daughter, Emily, took up residence in a modest house just a few doors down from the fallings. Michael was a journalist who had recently accepted a position with the Milbrook Gazette, and Susan was a social worker with experience in child welfare cases.

“Mom noticed something off about the Foing Kids right away,” says Emily Fletcher, now in her 40s. She had worked with traumatized children before and she recognized the signs. The way they flinched at sudden movements, how they never made eye contact, the fact that they always seemed to be watching Margaret out of the corners of their eyes as if they were afraid of missing a cue. Susan Fletcher began to make notes of her observations, documenting patterns of behavior that concerned her.

She also tried to befriend Margaret, hoping to get a closer look at the family dynamics. Margaret was initially receptive, perhaps seeing in Susan a potential ally in a community that was increasingly curious about her unusual family. The two women began to meet for coffee, and occasionally Susan would be invited to the falling home.

“It was during one of these visits that Susan noticed something strange.” “She told me about a room on the third floor,” says Emily. The door was always locked, but she could hear sounds coming from inside, shuffling, and sometimes crying. When she asked Margaret about it, Margaret said it was just storage and that the house made strange noises because it was old. But mom didn’t believe her.

Susan’s concerns grew when in the spring of 1993, she spotted a child she didn’t recognize peering from a thirdf flooror window of the foing house. The child, a girl with long dark hair, vanished from sight as soon as Susan looked up. When Susan mentioned this to Margaret, Margaret laughed it off, saying it must have been Elizabeth or Catherine.

But Susan had met all of the falling children by that point, and she was certain this was someone new. Around the same time, Michael Fletcher was working on a series of articles about adoption fraud for the Gazette. His research had led him to discover that several adoption agencies in Pennsylvania and neighboring states had been shut down in the 1980s for illegally placing children without proper documentation. Dad never specifically connected this to the Foings in his articles, says Emily.

But I remember him telling mom that the timeline matched up with when the Foings were adopting their first batch of kids. Whether by coincidence or design, it was shortly after Michael’s articles were published that the Foings announced they were adopting again.

This time, a set of twins named Peter and Paul, followed by a girl named Mary, bringing their total to 11 children. And once again, the adoptions happened with surprising speed. Looking back, it’s clear that they were taking advantage of loopholes in the system, says Cooper. They would work with different agencies, often in different states.

They would provide documentation from previous adoptions to establish themselves as experienced adoptive parents, and they would specifically request children from difficult backgrounds, children who were less likely to have complete records, children who might slip through the cracks. But why? What possible motive could the fallings have for adopting so many children? According to those who knew them best, Margaret’s desire for a large family seemed genuine. She had transformed herself into the maternal figure she had always wanted to be.

Howard, though less overtly enthusiastic about parenthood, appeared to indulge his wife’s wishes without complaint. It wasn’t about money, Cooper insists. The Foings were already wealthy. They didn’t need adoption subsidies, which were minimal in those days anyway. And it wasn’t about appearances.

If anything, having such a large family made them stand out in ways they might have preferred to avoid. The truth, when it finally began to emerge, was far more disturbing than anyone could have imagined. In the fall of 1994, Susan Fletcher was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Her illness progressed rapidly and by the spring of 1995 she was confined to her home receiving hospice care. It was during this time as she faced her own mortality that she decided to share her suspicions about the foings with someone who might be able to act on them. She called me to her bedside one night remembers Cooper who was then a junior detective with the Milbrook Police Department.

She had this file, pages and pages of notes she’d been keeping on the Foing family, observations, inconsistencies in the stories Margaret had told her, photographs she’d taken of the house, including that thirdf flooror window where she’d seen the unknown child. She made me promise that I would look into it after she was gone.

Susan Fletcher died on June 12th, 1995. Cooper kept his promise, though initially he proceeded with caution. The fallings were powerful in Milbrook and accusations against them would not be taken lightly. Cooper began by reviewing public records related to the family, property deeds, tax filings, and what little information was available about the adoptions.

Most of the adoption records were sealed, Cooper explains. But I was able to confirm that the Fings had worked with at least five different adoption agencies across three states. And I found something else interesting. Each time they adopted, they made a substantial donation to the agency involved. Not illegal necessarily, but definitely unusual.

Cooper also discovered that Howard Falling had established a trust fund for each of his adopted children. On the surface, this appeared to be a loving gesture, ensuring that the children would be financially secure as adults. But the terms of these trusts were strange.

The money would only be accessible when the child reached the age of 25 and only if they met certain conditions, including maintaining regular contact with their adoptive parents and not seeking information about their biological origins. It was about control. Cooper says everything the fallings did was about control. Armed with this information, Cooper decided to take a more direct approach.

He began driving by the Foing house regularly, noting who came and went. He interviewed neighbors, teachers who had briefly interacted with the Foing children during mandatory standardized testing, and former employees of the household. The staff never lasted long, Cooper notes.

They’d worked for the Foings for a few months, maybe a year at most, and then they’d suddenly leave town. No notice, no forwarding address. It was like they vanished. One former housekeeper, Maria Vasquez, had left Milbrook in 1991 after working for the fallings for just 6 months. Cooper tracked her down to a small town in Ohio where she was living under her maiden name. Initially, Vasquez refused to speak about her former employers.

But when Cooper showed her the file Susan Fletcher had compiled, something changed in her demeanor. She started crying, Cooper recalls. she said. So someone else knows, someone else has seen. And then she started talking and once she started, she couldn’t stop.

According to Vasquez, the foing children were subjected to a strict regimen designed to break their spirits and ensure their compliance. They were forced to follow elaborate rules that changed constantly, making it impossible to avoid punishment. They were isolated from each other with each child assigned a separate bedroom and forbidden from entering the others rooms.

They were required to address Howard and Margaret as sir and madam, never as mom and dad. But the worst thing, Cooper says, was what Maria told me about the third floor. She said there were three rooms up there that were always kept locked.

She was responsible for leaving food outside these rooms three times a day, but she was never allowed to see who was inside. She could hear them though, children’s voices, sometimes crying, sometimes singing to themselves. When she asked Margaret about it, Margaret told her that these were children with special needs who required isolation for their own safety.

Vasquez had finally left after witnessing Margaret punishing James, who was then about 11, for speaking during dinner without being spoken to first. The punishment had involved forcing the boy to stand in a corner all night with Margaret checking on him hourly to ensure he hadn’t moved. Maria said she couldn’t be part of it anymore.

Cooper says she packed her things that night and left before dawn. She was afraid not just of losing her job, but of what the fallings might do if they knew she disapproved. With Vasquez’s testimony and Susan Fletcher’s notes, Cooper felt he had enough to justify a more formal investigation. He took his findings to his superior, Chief Raymond Wallace, expecting support.

Instead, he was told to drop the matter. The chief said there wasn’t enough evidence to warrant an investigation into such a respected family, Cooper recalls. He reminded me that Howard Falling was friends with the mayor, the district attorney, and half the town council.

He suggested that I was letting my friendship with the Fletchers cloud my judgment. Frustrated, but undeterred, Cooper continued his investigation unofficially, working on his own time and keeping his notes at home rather than at the station. He was particularly interested in the identities of the children allegedly being kept on the third floor.

Children who were not among the 11 officially adopted by the fallings. His breakthrough came from an unexpected source. Emily Fletcher, then 19 and studying journalism like her father, had not forgotten her mother’s concerns about the falling family. She had been conducting her own research focusing on missing children cases from the regions where the Foings had adopted. I found a pattern.

Emily says in at least three instances when the Foings adopted a child from a particular area, there was a report of another child going missing from the same area within a month. These were always children from vulnerable populations, foster kids, children of migrant workers, children from families dealing with addiction or poverty, children who might not be missed right away or whose disappearances might not generate much attention.

Emily shared her findings with Cooper, who used his law enforcement access to dig deeper. He discovered that in each case Emily had identified, the missing child had never been found. And in each case, the investigation had been cursory at best. It was like these kids didn’t matter to the system, Cooper says bitterly, like they were disposable.

Armed with this new information, Cooper decided to bypass Chief Wallace and take his case directly to the Pennsylvania State Police. He compiled a detailed report, including Vasquez’s testimony, Susan Fletcher’s notes, Emily’s research, and his own findings.

He sent it to a contact at the state level, a former colleague named Lisa Harper, who now worked with a task force on crimes against children. Harper took the report seriously. Within a week, she had secured a warrant to search the Foing residence. But obtaining the warrant was only the first hurdle.

The execution of that warrant would prove to be one of the most challenging operations of Cooper’s career. We knew we had to move quickly and decisively, Cooper explains. If the fallings had any warning, they might destroy evidence or worse, harm the children. But we also knew that they had connections. If word of the impending search reached them through official channels, the whole operation could be compromised.

Harper assembled a team of state troopers and agents from the newly formed child exploitation and obscenity section of the Department of Justice. Cooper was included as a local liaison. The plan was to execute the warrant at dawn when the household would likely be asleep and at its most vulnerable. On the morning of October 23rd, 1995, a convoy of unmarked vehicles approached the falling estate. The officers moved swiftly, securing the perimeter before announcing their presence.

Howard Falling, dressed in a silk bathrobe, answered the door. According to Cooper, he showed no surprise at the sight of law enforcement on his doorstep. He was expecting us. Cooper says somehow he knew we were coming. He invited us in as if we were guests arriving for a dinner party.

He was completely calm, completely in control. Margaret falling was a different story. When she realized what was happening, she became hysterical, screaming that they had no right to invade her home, that they were traumatizing her children. She had to be restrained when she physically attacked one of the female officers.

The search of the house began methodically with teams assigned to different areas. The 11 known foing children were found in their bedrooms, all awake despite the early hour, all dressed and sitting on the edges of their beds as if awaiting inspection. They didn’t react to our presence, Harper would later report. Not with fear, not with curiosity, not with anything. It was as if they had been emptied out.

The officers attempted to interview the children, but they were met with scripted responses that revealed nothing. Even James, who was by then 17 and legally able to speak for himself, would only say, “Sir and madam provide everything we need. We are happy here.” The true horror was discovered on the third floor.

As Vasquez had testified, there were three locked rooms. When the officers broke down the doors, they found three children, a girl of about 10 and two boys who appeared to be around eight. Unlike the falling children downstairs, these children reacted with terror to the presence of strangers.

They cowered in corners, hiding their faces and whimpering. The conditions were deplorable, Cooper says, his voice tight with anger even decades later. The rooms were bare except for mattresses on the floor. There were no toys, no books, nothing to suggest that these were children’s rooms. The windows were covered with blackout curtains nailed to the frames. and the smell.

The smell was overwhelming. These children had been living in their own filth. Medical examinations would later reveal that all three children were severely malnourished and showed signs of physical abuse. None of them could speak English fluently, suggesting that they had been taken from non-English-speaking households, and none of them appeared in any official record.

No birth certificates, no adoption papers, nothing to indicate that they legally existed. They were ghosts, Cooper says. Children who had been erased from the world. The discovery of these hidden children transformed what had been a case of suspected child abuse into something far more sinister.

The FBI was called in and the investigation expanded to include potential charges of kidnapping, human trafficking, and falsification of federal documents. Howard and Margaret Foing were arrested on the spot. As they were being led away, Margaret broke free from the officer holding her and ran to the staircase, screaming something in a language that none of the officers recognized.

Later analysis would suggest it was a form of glosselia or speaking in tongues, a practice associated with certain religious traditions, but also sometimes observed in individuals experiencing extreme psychological stress. That was when I first began to wonder if there was a religious component to what the fallings were doing. Cooper says, “Up until that point, I had assumed it was about control, about Margaret’s twisted desire for a large family that she could shape however she wanted.

But that moment on the staircase, it hinted at something deeper, something ritualistic.” As the investigation progressed, this suspicion would be confirmed in ways that shocked even seasoned law enforcement officials. With the Foings in custody, the focus shifted to understanding the full scope of their crimes and more urgently identifying and helping their victims. The three children found on the third floor were placed in emergency foster care.

While the 11 officially adopted children were temporarily housed in a group home designed for traumatized youth. Interviewing the children proved challenging. The 11 adopted children maintained their scripted responses, refusing to deviate from what they had clearly been taught to say. The three hidden children, meanwhile, were too traumatized to communicate effectively.

They flinched at any sudden movement, refused to make eye contact, and became hysterical when separated from each other. “It was as if they only trusted each other,” says Dr. for Evelyn Marorrow, a child psychologist who worked with the children, which made sense given what they had endured. They had been kept in isolation, their only human contact being with each other and periodically with Margaret, who would visit them to administer what she called treatments. These treatments, as described by the children once they

began to communicate through art therapy, involved Margaret forcing them to drink a bitter liquid that made them sleepy, after which she would recite what sounded like prayers or incantations over them. Sometimes she would draw symbols on their bodies with a dark liquid that might have been ink or blood.

The ritual aspect was undeniable, Dr. Marorrow says, “But we couldn’t identify any known religious tradition that matched what the children described. It seemed to be something Margaret had created, a personal mythology that she was imposing on these vulnerable children. While Dr.

Marorrow worked with the children, Cooper and the federal agents searched the Foing House for evidence. In Howard’s study, they discovered a hidden safe containing multiple sets of falsified adoption papers as well as large sums of cash in various currencies. But the most disturbing find was a leatherbound journal written in Margaret’s hand.

The journal, which spanned nearly 20 years, detailed Margaret’s mission to create what she called the perfect family. According to her writings, she believed that children were born with sins that needed to be purged before they could become truly pure.

The purging process involved breaking the child’s connection to their birth family, stripping away their original identity, and reshaping them according to Margaret’s vision. She saw herself as a savior. Cooper says in her mind, she wasn’t abusing these children. She was saving them. She was cleansing them of their past and giving them a new purified existence as members of her family.

The journal also revealed that Margaret classified the children into two categories, the redeemable and the vessels. The redeemable were the 11 officially adopted children whom Margaret believed could be purified through strict discipline and religious indoctrination. The vessels, the three children found on the third floor, as well as others who had come before them, served a different purpose.

According to Margaret’s writings, the vessels were children whose souls were already too corrupted to be saved. Cooper explains, “Instead, they were to be used as receptacles for the sins that were being purged from the redeemable children. It was a twisted form of transference.

Margaret believed she could extract the evil from one child and place it into another. This explained the treatments described by the hidden children. Margaret was performing rituals designed to transfer what she perceived as sin or evil from her adopted children to these unfortunate vessels. And once a vessel was full, a state Margaret claimed to be able to identify by looking into their eyes.

They would be discarded. The journal did not explicitly state what happened to these discarded vessels, but it did reference a resting place on the Foing property where the filled ones sleep until judgment day. This led to the most gruesome phase of the investigation, the search of the Foing estate’s grounds.

In a wooded area at the far edge of the property, cadaver dogs alerted to a patch of earth that appeared undisturbed to the human eye. Excavation revealed the remains of five children buried in shallow graves marked only with small stones. The medical examiner estimated that the oldest burial was about 14 years old, which would place it around 1981, shortly after the Foings adopted James, Cooper says. The most recent was probably less than a year old.

All of the children had died from similar causes, a combination of malnutrition, dehydration, and exposure. They had essentially been neglected to death. Forensic anthropologists worked to identify the remains, a process complicated by the lack of dental records or DNA samples for comparison. Eventually, three of the five children were tenatively identified as matching the descriptions of children reported missing from areas where the fallings had adopted.

Maria Gomez, age nine, reported missing from a migrant worker camp in central Pennsylvania in 1981. Tyrell Washington, age 7, who disappeared from a Pittsburgh housing project in 1985, and Alexi Petro, age 8, the son of Russian immigrants who vanished from his front yard in Philadelphia in 1990. The other two children remained unidentified, referred to in official records only as Jane Doe number one and John Doe number three. That’s the thing that still haunts me.

Cooper says, “Those two kids, someone must have loved them. Someone must have missed them, but they died without names and they were buried without ceremony. It’s as if they never existed at all. As the evidence mounted, the case against the fallings seemed irrefutable, but the legal proceedings would prove to be as twisted and complex as the crimes themselves.

Howard Falling hired a team of high-powered defense attorneys who immediately began working to distance him from his wife’s actions. They painted a picture of Howard as an unwitting participant, a man so consumed by his financial dealings that he was oblivious to what was happening in his own home.

They pointed out that Howard was frequently away on business, sometimes for weeks at a time, and that Margaret had been the primary caregiver for all of the children. “It was a transparent strategy,” says assistant US attorney Meredith Lane, who prosecuted the case. Howard wanted to save himself by sacrificing his wife, but the evidence didn’t support his claim of ignorance. He had signed all of the fraudulent adoption papers.

He had established the trust funds with their controlling conditions. He had built the locked rooms on the third floor. He might not have performed the rituals, but he had enabled them at every turn. Margaret, meanwhile, was deemed incompetent to stand trial after a psychological evaluation revealed severe delusional disorder with religious preoccupation. She was committed to a secure psychiatric facility where she remained until her death in 2008.

Howard denied the opportunity to shift all blame to his wife, changed tactics. His attorneys began negotiating a plea deal, offering Howard’s cooperation in exchange for a reduced sentence. Specifically, they promised that Howard could provide information about other children who had been vessels, but whose remains had not been found on the property. It was a gut-wrenching decision, Lane admits.

On one hand, we wanted Howard to face the harshest possible penalties for his crimes. On the other hand, the possibility of bringing closure to more families, of giving names to more lost children, that was hard to ignore. In the end, a deal was struck.

Howard pleaded guilty to multiple counts of child endangerment, kidnapping, and falsification of federal documents. In exchange for his cooperation and testimony, he received a sentence of 25 years to life with the possibility of parole after 20 years. Howard’s information led investigators to three additional burial sites, each on properties that the fallings had owned briefly before selling.

a lakehouse in upstate New York, a hunting cabin in rural West Virginia, and a beach house on the Maryland shore. In total, the remains of eight more children were recovered, bringing the total to 13 victims. 13 vessels for 12 redeemable children, Cooper notes. In Margaret’s twisted logic, there had to be more vessels than redeemable children because some of the vessels would become filled more quickly than others. It was all part of her sick arithmetic of salvation.

Of these additional eight victims, five were eventually identified. Lucia Diaz, age 9,Wami Johnson, age 7, Tran Nonguan, age 10, Sarah Black Feather, age 8, and Dmitri Kowalsski, age 6. All had been reported missing between 1983 and 1992. And all came from marginalized communities where law enforcement resources were stretched thin and missing children cases often went uninvestigated. The Foings were predators, Lane says.

They deliberately targeted children who wouldn’t be missed or whose disappearances wouldn’t generate headlines. They exploited the same systemic failures that they used to adopt their redeemable children without proper scrutiny. As for those 12 redeemable children, their fates were varied and in many cases tragic.

James, the oldest, committed suicide in 1998, 3 years after the Foings were arrested. Elizabeth developed severe anorexia and has been in and out of treatment facilities for most of her adult life. Thomas, whose broken arm had first brought attention to the family, disappeared after turning 18 and has never been found.

Some of the younger children were eventually adopted by new families, while others remained in the foster care system until they aged out. The damage was too deep, says Dr. Marorrow. These children had been systematically brainwashed from a very young age. They had been taught that their worth was tied to their purity and that purity could only be achieved through suffering.

It’s not something you can undo with a few years of therapy. The three children found on the third floor, later identified as Sophia Herrera, age 10. Matteo Herrera, age 8, and Carlos Herrera, age 8, were eventually reunited with their family. They had been taken from a rural area near San Diego, where their parents were migrant workers.

The parents had reported their children missing, but the local police had suggested that the family had simply moved on, as migrant families often did. It was a miracle that they were found alive. Cooper says, “If we had waited even a few more months, “Well, based on Margaret’s journal, Sophia was already being described as nearly filled. She would have been the next to be discarded.

” Howard Falling died in prison in 2011, having served 16 years of his sentence. He never expressed remorse for his actions, maintaining until the end that he had only been trying to help his wife realize her dream of a large family. His estate, valued at several million dollars, was divided among the surviving victims as part of a civil settlement.

The Foing House on Elm Street was demolished in 1997 and the land was converted into a community garden dedicated to the memory of the children who had died there. Each year on the anniversary of the falling’s arrest, the people of Milbrook gather in the garden for a vigil, lighting 13 lanterns for the 13 vessels and 12 candles for the 12 redeemable children whose lives were forever altered by Howard and Margaret falling.

It’s not enough. Cooper says nothing could ever be enough to make up for what those children suffered, but it’s something. It’s a way of saying, we remember, we acknowledge what happened here, and we’re sorry we didn’t see it sooner.

The case of the fallings has had lasting impacts on adoption laws and procedures in Pennsylvania and beyond. The Foing Act passed by the Pennsylvania legislature in 1998 requires more rigorous background checks for adoptive parents, limits the number of children that can be adopted by a single family within a specific time frame, and mandates regular home visits by social workers for the first 5 years after an adoption. The system failed these children.

Lane says, “We all failed them. The neighbors who noticed something off but didn’t speak up. The doctors who saw the signs of abuse but didn’t push harder for answers. The officials who were too impressed by Howard’s wealth and status to ask the hard questions.

Even law enforcement, we should have taken Susan Fletcher’s concerns more seriously from the beginning. But perhaps the most haunting aspect of the falling case is the knowledge that there might be more victims who will never be found. Howard’s cooperation was limited to the children buried on properties directly linked to the fallings.

But given the family’s extensive travels and Howard’s business dealings across multiple states, it’s possible, even likely, that there were other vessels whose remains are still undiscovered. I’ve made peace with the fact that we’ll never know the full extent of the falling’s crimes. Cooper says, “But I haven’t made peace with the fact that there are parents out there who still don’t know what happened to their children. That’s why I keep going back to the case files, even in retirement.

That’s why I still follow up on every lead, no matter how unlikely, because those children deserve to have their names. They deserve to have their stories told. And so, the macabra history of the fallings continues to unfold, even decades after their crimes were first discovered.

It serves as a reminder of the darkness that can hide behind a facade of respectability, of the vulnerable children who slip through the cracks of our society, and of the terrible consequences when those entrusted with their care betray that sacred responsibility. Before we end today’s episode, I want to take a moment to acknowledge the families of the identified victims.

Maria Gomez, Terrell Washington, Alex Petro, Lucia Diaz, Kwaame Johnson, Tran Guuan, Sarah Black Feather, and Dmitri Kowalsski. Their lives were cut short by unimaginable cruelty. But in telling their stories, we ensure that they are not forgotten. And for Jane Doe number one, John Doe number three, and the three remaining unidentified children.

We may not know your names, but we bear witness to your suffering. You matter. You have always mattered. This has been the Ghastly Journal. Remember to subscribe and turn on notifications so you never miss an episode. If you or someone you know has information about missing children, please contact the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 1 800 the lost. Sometimes even decades later, the truth can still come to light.

Until next time, stay vigilant. The darkest deeds often happen in the places we least expect. In the decades since the Foing case first shocked the nation, numerous theories have emerged about the origins of Margaret’s disturbing belief system.

While the official investigation focused primarily on identifying victims and building a legal case against the fallings, researchers and true crime enthusiasts have continued to probe the psychological and potentially cultural roots of Margaret’s rituals. Dr. Eliza Montgomery, a professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania, has spent years examining Margaret’s journal and court testimonies.

What’s particularly interesting about Margaret’s belief system is that it doesn’t neatly align with any established religious tradition. Montgomery explains it contains elements that might seem familiar. The concept of sin, the idea of purification through suffering, ritualistic cleansing, but they’re combined in ways that are entirely idiosyncratic. According to Montgomery, Margaret’s background might offer some clues.

Born Margaret Phelps in 1945, she was raised in a small farming community in rural Minnesota. Her parents were described by neighbors as deeply religious but private people who rarely attended community events and kept their children home from school whenever possible. There were rumors in the town about unusual religious practices in the Phelps household.

Montgomery says nothing specific, nothing that anyone could prove, but enough to make the family something of an enigma. The few people still living who remember the Phelps family described them as odd and secretive. At 18, Margaret left home to attend nursing school in Minneapolis, a move that apparently caused a permanent rift with her family.

According to school records, she never returned home for holidays, and none of her family attended her graduation. By all accounts, she was a dedicated student who specialized in pediatric care, drawn to working with children from the beginning of her career.

There’s a gap in our understanding of Margaret’s life between her graduation from nursing school in 1965 and her marriage to Howard in 1976. Montgomery notes. We know she worked at several hospitals across the Midwest, never staying in one place for more than a year or two. And we know that she spent some time in Europe in the early 1970s, though the exact purpose of this trip remains unclear.

It was during this European sojourn that Margaret might have encountered the obscure religious texts that later influenced her beliefs. Among her possessions seized during the investigation was a collection of manuscripts, some dating back to the 17th century that dealt with various esoteric traditions. These included works on alchemy, gnosticism, and certain mystical practices that involve the concept of spiritual transference.

the idea that qualities like sin or virtue could be moved from one vessel to another. These weren’t mainstream religious texts. Montgomery emphasizes they were obscure, often fragmentaryary works that would have been difficult for a casual reader to find.

Margaret must have sought them out deliberately, suggesting a pre-existing interest in these concepts. By the time Margaret met Howard falling at a charity gala in Pittsburgh in 1975, she had developed the framework of her belief system, a system she apparently kept hidden from her husband to be, at least initially.

Howard, by all accounts, was not a religious man. His interest was in accumulating wealth and social status, goals he pursued with single-minded determination. It’s an open question whether Howard ever fully understood or shared Margaret’s beliefs, says Cooper. In his testimony, he claimed that he thought her interest in adoption stemmed from a genuine desire to help underprivileged children, combined with her inability to have biological children. He said he only became aware of the religious aspect gradually, and by then he was too

deeply involved to extricate himself. But Cooper remained skeptical of this claim. Howard was an intelligent, observant man. The idea that he could live in that house for 15 years and not know what was happening, it stretches credul to the breaking point. Dr. Montgomery offers another perspective.

I think Howard might have seen Margaret’s beliefs as a form of eccentricity, something to be humored rather than challenged. There’s evidence that he was genuinely in love with her, at least in the beginning. And people in love often overlook or rationalize behaviors that would alarm an outside observer. Whatever Howard’s level of understanding or complicity, there’s no doubt that he enabled Margaret’s actions through his financial resources and social connections.

Without Howard’s money to facilitate quick adoptions and buy properties where vessels could be hidden or buried without his status to deflect suspicion and intimidate potential whistleblowers, Margaret’s mission might have been discovered much sooner. They were a perfect storm, Cooper says grimly. Margaret with her twisted vision, Howard with his means to make it reality.

And caught in the middle were 25 children whose lives were destroyed. The 25 children Cooper refers to include the 12 redeemable children who were officially adopted and subjected to years of psychological and sometimes physical abuse, and the 13 vessels who suffered even more extreme neglect before ultimately being killed when Margaret deemed them filled with the sins she believed she had extracted from her adopted children.

Of the 12 adopted children, only nine are still alive today. In addition to James’ suicide and Thomas’s disappearance, Catherine died of a drug overdose in 2007 at the age of 28. The surviving nine have largely avoided public attention, changing their names and attempting to build lives away from the shadow of their traumatic childhoods. Elizabeth, now in her 40s, is the only one who has spoken publicly about her experiences.

In a rare interview given to a documentary filmmaker in 2015, she described the constant fear that permeated the Foing household. “We were always afraid of disappointing them,” she said. “Sir and madam, that’s what we had to call them, had these elaborate rules that changed all the time.

You never knew what might trigger a punishment. Something that was acceptable one day could be forbidden the next. It kept us constantly on edge, constantly vigilant. Elizabeth also spoke about the cleansing rituals that Margaret performed on the children. She would make us drink this tea that tasted horrible, and then she’d make us kneel in this circle she’d drawn on the floor.

She’d recite these long passages in a language none of us understood, and she’d touch our foreheads with this cold, wet finger. Sometimes she’d make cuts on our arms, small ones, nothing that would leave obvious scars, and collect the blood in a little silver cup. According to Elizabeth, the children were told that these rituals were necessary to remove the badness they had brought with them from their previous lives. Madam said, we were born with sin inside us, like a disease.

Elizabeth recalled. She said our birth parents had infected us and only she could cure us. If we resisted the treatments, she said the sin would grow until it consumed us and then we’d have to go live upstairs with the bad children. The bad children, Margaret’s vessels, were occasionally shown to the adopted children as a warning.

She’d take us up there one at a time and make us look at them through this little window in the door. Elizabeth said. They were always so thin, so dirty, and their eyes, they looked dead already, you know, like there was nothing inside them anymore. Madam would say, “This is what happens to children who don’t accept the treatment. This is what happens when the sin takes over.

” This psychological torture combined with physical deprivation and isolation created a environment of complete control. The children were entirely dependent on Margaret and Howard for everything. Food, shelter, human contact, and the definition of reality itself. It was a classic cult dynamic, says Dr. Marorrow. The leader defines what is true and false, good and evil.

The followers are cut off from any outside influence that might contradict this definition. And over time, the followers internalize the leader’s worldview to such an extent that they can no longer distinguish between their own thoughts and the thoughts that have been implanted.

This explains why even after being removed from the Foing home, many of the children continued to defend their adoptive parents and to insist that they had been happy there. It wasn’t Stockholm syndrome in the classical sense. Dr. Marorrow clarifies it was more fundamental than that. These children had never known any other reality.

They had no framework for understanding that what had happened to them was abuse. The process of healing for these children was slow and painful. Some, like James, never managed to overcome the trauma. Others, like Elizabeth, have spent their lives in a cycle of progress and relapse, forever struggling with the psychological wounds inflicted during their formative years.

The tragedy of the falling case isn’t just the 13 children who died. Dr. Marorrow says it’s also the 12 who lived but were never allowed to develop into the people they might have been. Their potential was stolen from them just as surely as the lives of the vessels were stolen.

In the years since the Foing case, researchers have identified similar patterns in other cases of extreme child abuse, particularly those with religious or cult-like elements. The combination of isolation, ritualistic behavior, and the exploitation of children’s natural dependency creates conditions in which almost unimaginable cruelty can flourish.

What makes the Foing case unique, says Montgomery, is the scale and duration of the abuse, as well as the way it was hidden in plain sight. This wasn’t a compound in the wilderness or a closed religious community. This was a respected family in a typical American town. The Foings went to church on Sundays.

They attended community events. Howard served on local boards. They were to all outward appearances pillars of the community. This facade of normaly allowed the fallings to operate for nearly two decades without serious scrutiny. And when concerns were raised by Dr. Chen after Thomas’s injury, by Susan Fletcher after her observations of the family, they were too easily dismissed by those with the power to intervene. That’s the lesson we should take from this case, Cooper insists.

Not just the spectacular horror of what happened inside that house, but the ordinary failures that allowed it to continue. The neighbor who saw something odd but didn’t want to seem nosy. The official who accepted a flimsy explanation because the alternative was too disturbing to contemplate.

The colleague who noticed something wrong but didn’t want to risk their career by speaking up. These everyday failures of courage and responsibility multiplied across a community in spanning years created the conditions in which the Foing’s crimes could flourish. And according to Cooper, similar dynamics continue to enable child abuse today.

The names and circumstances change, but the pattern remains the same. He says someone notices something wrong, but they tell themselves it’s not their business. or they report it, but they don’t follow up when nothing seems to happen. Or the system gets involved, but it’s too overworked and underfunded to provide the kind of sustained attention that might reveal the truth.

This systemic failure is particularly pronounced when it comes to children from marginalized communities. The very children the Foings targeted as their vessels. Children from poor families, immigrant children, children of color, children in the foster care system, all are statistically more likely to be victims of abuse and less likely to receive thorough protection from that abuse. The Foing case isn’t ancient history.

Cooper says it’s a warning about what can happen when we fail to protect our most vulnerable children. And it’s a reminder that sometimes the monster isn’t hiding under the bed or in the closet. Sometimes the monster is the respected neighbor down the street, the one everyone thinks is such a pillar of the community.

As for Margaret Falling, she spent the last 13 years of her life in a secure psychiatric facility. never legally tried for her crimes due to her ongoing mental incompetence. According to staff reports, she continued to perform her rituals in private, using whatever materials she could find or fashion.

She maintained until her death that she had been doing God’s work, saving children’s souls through a sacred process of transference. In one of her final journal entries written just months before her death from breast cancer in 2008, Margaret wrote, “They think they’ve stopped the mission, but they don’t understand. The work continues on another plane. The vessels are filled, the redeemable are cleansed, and when judgment comes, all will see that I was right. All will know that I was chosen for this holy purpose.

” Howard, meanwhile, spent his years in prison writing a memoir titled Blind Trust, in which he portrayed himself as a victim of Margaret’s manipulation. The manuscript was never published as the courts ruled that Howard could not profit from his crimes.

But copies have circulated among researchers and true crime enthusiasts, providing insight into the mind of a man who enabled unspeakable cruelty while maintaining his own innocence. I love my wife, Howard wrote in the manuscript’s conclusion. I believed in her goodness, her kindness, her desire to help children in need. By the time I realized the depth of her delusion, I was trapped by my love for her, by my fear of losing everything we had built together, and by my own complicity and what had already occurred.

I am not blameless, but I am not the monster they have made me out to be. I am simply a man who loved unwisely and too well. Cooper, who has read the manuscript, dismisses Howard’s self-prayal. It’s self-serving nonsense. He says Howard wasn’t some love struck victim. He was an active participant in the abuse and exploitation of 25 children.

He may not have shared Margaret’s religious fervor, but he was willing to benefit from it. from the adoration of a community that saw them as saviors. From the control they exerted over their victims, from the sick dynamic they created together. Regardless of Howard’s motivations or level of belief, the consequences of his actions and his failures to act were the same. Children suffered and died. Lives were destroyed.

And a community was left to grapple with the knowledge that such darkness had existed in their midst, unrecognized and unchallenged for far too long. Today, the Foing case is studied by law enforcement officers, social workers, psychologists, and religious scholars. It serves as a case study in how abuse can be hidden behind wealth and status.

How destructive belief systems can develop and flourish in isolation, and how the most vulnerable members of society, children, can fall through the cracks of the systems designed to protect them. If there’s any silver lining to this terrible story, Cooper says, it’s that it has made us more vigilant.

It has changed laws and procedures. It has made us more willing to ask difficult questions and to follow up when the answers don’t seem quite right. It has reminded us that we all have a responsibility to protect children, not just the ones in our own families, but all children. And perhaps that is the legacy of the Foing case.

Not just a tale of horror and depravity, but a call to action. A reminder that the darkest deeds often happen in the places we least expect, and that our willingness to see, to speak, and to act can make the difference between life and death for those who cannot protect themselves.

In the community garden that now stands where the Foing House once loomed, 25 trees have been planted, 12 oak trees for the redeemable children, 13 willows for the vessels. Each year they grow taller and stronger, their branches reaching toward the sky in silent testimony to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring hope that from even the darkest soil, new life can emerge.

And so we end our exploration of the macabra history of the fallings. A story of horror, yes, but also a story of courage. The courage of Susan Fletcher, who first raised the alarm. The courage of Maria Vasquez, who fled the House of Horrors but didn’t forget what she had seen.

The courage of Detective Richard Cooper, who persisted in his investigation despite official resistance. And most of all, the courage of the children who survived, Elizabeth and the others who continue to live their lives day by day, carrying burdens no child should ever have to bear. May we honor their courage with our vigilance. May we ensure that such horrors never again hide in plain sight behind respectability and wealth and the reluctance to ask uncomfortable questions. And may we never forget the names of those who didn’t survive.

Maria, Tyrell, Alexe, Lucia,Wame, Tron, Sarah, Dimmitri, and the five children whose names we may never know but whose lives mattered just the same. This has been the Ghastly Journal. Until next time, remember the most important stories are often the ones that are hardest to tell. Thank you for listening.

News

Single Dad Was Tricked Into a Blind Date With a Paralyzed Woman — What She Told Him Broke Him

When Caleb Rowan walked into the cafe that cold March evening, he had no idea his life was about to…

Doctors Couldn’t Save Billionaire’s Son – Until A Poor Single Dad Did Something Shocking

The rain had not stopped for three days. The small town of Ridgefield was drowning in gray skies and muddy…

A Kind Waitress Paid for an Old Man’s Coffee—Never Knowing He Was a Billionaire Looking …

The morning sun spilled over the quiet town of Brier Haven, casting soft gold across the windows of Maple Corner…

Waitress Slipped a Note to the Mafia Boss — “Your Fiancée Set a Trap. Leave now.”

Mara Ellis knew the look of death before it arrived. She’d learned to read it in the tightness of a…

Single Dad Accidentally Sees CEO Changing—His Life Changes Forever!

Ethan Cole never believed life would offer him anything more than survival. Every morning at 5:30 a.m., he dragged himself…

Single Dad Drove His Drunk Boss Home — What She Said the Next Morning Left Him Speechless

Morning light cuts through the curtains a man wakes up on a leather couch his head is pounding he hears…

End of content

No more pages to load