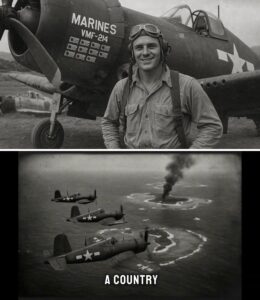

Leading this formation is a man who shouldn’t even be here. Major Gregory Papy Boyington. A 31-year-old pilot with a checkered past, a drinking problem, and a reputation for insubordination that nearly ended his military career before it began. Behind him fly 23 other misfits, rejects, and troublemakers.

Pilots that other squadrons didn’t want, couldn’t handle, or had given up on entirely. They call themselves VMF214, but the world would come to know them by another name, the Black Sheep Squadron. And on this particular morning, they’re about to encounter something that will leave Japanese pilots across the Pacific questioning everything they thought they knew about American fighter tactics. What happened next would become the stuff of legend.

A story so extraordinary that even today historians debate whether it could possibly be true. But for the Japanese Zero pilots who witnessed it firsthand, there was no debate at all. They had just seen something that defied every principle of aerial combat they’d been taught.

Something that would haunt their dreams and reshape their understanding of what American pilots were capable of. This is the story of how a squadron of misfits became the most feared fighter unit in the Pacific and why Japanese pilots couldn’t believe what they were seeing when the black sheep came to rule the skies. To understand the shock that rippled through Japanese aviation circles in late 1943, we need to step back and examine the state of the Pacific War at that crucial moment in history.

By October 1943, the tide was beginning to turn, but the outcome was far from certain. For nearly 2 years, Japanese pilots had dominated Pacific skies with an almost mystical superiority. Their Mitsubishi A6M0 fighters had earned a reputation for invincibility that bordered on the supernatural. These aircraft were marvels of engineering.

Lightweight, maneuverable, and flown by pilots who had honed their skills in the brutal crucible of the China War. The Zero’s advantages were undeniable. At just 5,300 lb fully loaded, it could outturn virtually any Allied fighter. Its 20 mm cannons packed devastating firepower, and its range was extraordinary, capable of flying over 1 1900 m on internal fuel alone.

But perhaps most importantly, it was flown by pilots who had been training for war since the mid 1930s. These weren’t weekend warriors or hastily trained recruits. Japanese naval aviators underwent years of rigorous preparation that would have broken lesser men. They practiced formation flying until they could maintain perfect positioning in their sleep.

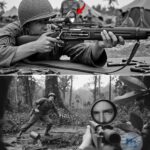

They studied aerial gunnery until they could hit targets with mathematical precision, and they embraced a warrior code that valued honor above life itself. By contrast, American pilots in early 1942 seemed almost amateur-ish, flying outdated aircraft like the Brewster Buffalo and early model Wildcats. They were consistently outmaneuvered, outgunned, and outfought.

The statistics were sobering. In some early engagements, Japanese pilots achieved kill ratios of 10 to1 or better. But something was changing. By 1943, American industry was hitting its stride, producing aircraft at a rate that staggered the imagination. More importantly, a new generation of fighters was reaching the Pacific.

Aircraft like the F6F Hellcat and the F4U Corsair that could finally match the Zero’s performance. The Corsair in particular represented a quantum leap in American fighter design. With its distinctive inverted gull wing and massive Prattton Whitney R2800 engine producing 2,000 horsepower, it was a brute force solution to the zero problem.

Where the Japanese fighter relied on finesse and agility, the Corsair brought raw power and speed to the equation. Yet, even with superior aircraft, American pilots were still learning how to fight effectively against an enemy that had perfected their tactics through years of combat experience. The learning curve was steep, and the price of education was measured in blood.

This was the world that VMF214 entered in September 1943. A theater where Japanese pilots still held psychological dominance despite their increasingly desperate strategic situation. What they were about to encounter would shatter that dominance forever. The story of VMF214 begins not with glory, but with failure and frustration.

In the summer of 1943, the Marine Corps faced a peculiar problem. What to do with pilots who didn’t fit the mold of traditional military aviators? These were men who could fly, some of them brilliantly, but who chafed under military discipline, questioned orders, or simply couldn’t get along with their commanding officers. They were the square pegs that wouldn’t fit into the round holes of conventional squadrons.

Under normal circumstances, they might have been quietly transferred to training duties or administrative positions. But 1943 was not a normal time, and the Marine Corps couldn’t afford to waste talent, no matter how unconventional. Enter Gregory Boington, a man whose own military career read like a cautionary tale of wasted potential.

Born in Idaho in 1912, Bington had graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in aeronautical engineering. He joined the Marines in 1935, earned his wings, and seemed destined for a solid, if unremarkable, military career. But Boington had demons. He drank too much, fought with his superiors, and accumulated debts that threatened to destroy his career.

By 1941, facing a court marshal for insubordination, he made a desperate choice. He resigned from the Marines and joined the American volunteer group, the famous flying tigers, fighting for China against Japanese aggression. In China, Boyington found his calling.

Flying the shark-mouthed P40 Warhawks of the Flying Tigers, he shot down six Japanese aircraft and learned valuable lessons about fighting zeros that would serve him well in the years to come. But even in China, his personal problems followed him. He clashed with Clare Chan, the Tiger’s legendary commander, and eventually found himself persona non grata, even among that group of misfits and adventurers.

When the Flying Tigers disbanded in 1942, Boington returned to the United States, a man without a country, militarily speaking. The Marines were reluctant to take him back given his history of disciplinary problems. But with the Pacific War consuming pilots at an alarming rate, they eventually relented, reinstating him with his former rank of major.

For over a year, Boyington languished in statesside training commands, watching younger, less experienced pilots ship out to the Pacific while he remained stuck in administrative limbo. It was a bitter pill for a man who knew he had the skills to make a difference in combat. The opportunity for redemption came in an unexpected form. In August 1943, Marine Corps planners realized they had a collection of replacement pilots scheduled for the Pacific who didn’t quite fit into existing squadron structures. Some were veterans returning from earlier tours who had personality

conflicts with their former units. Others were skilled pilots whose attitudes made them unwelcome in traditional squadrons. Rather than try to force these square pegs into round holes, someone had a brilliant idea. Why not create a new squadron specifically designed for misfits? Give them to Boyington himself, the ultimate misfit, and see what happened.

And so VMF214 was born, not from careful planning or military tradition, but from necessity and desperation. Boington was given cart blah to select his own pilots from the pool of available replacements. And he chose men who reminded him of himself. Talented but troubled, skilled but stubborn, capable but unconventional.

There was Captain Stan Bailey, a veteran pilot whose aggressive tactics had earned him both victories and reprimands. First, Lieutenant Bob McClur, whose mechanical aptitude was matched only by his disdain for military protocol. Technical Sergeant Henry Miller, an enlisted pilot whose workingclass background and blunt manner made him an outsider among the officer corps.

One by one, Boyington assembled his collection of misfits, rejects, and troublemakers. They were men who had been written off by the system, pilots whose careers seemed destined for mediocrity or failure. But Boington saw something else in them, a hunger to prove themselves, a desire to show the world that being different didn’t mean being inferior. The squadron’s unofficial motto said it all. We’re not the best, but we’re the most colorful.

It was a self-deprecating joke that mastered deeper truth. These men had nothing left to lose and everything to prove. The transformation of VMF 214 from a collection of misfits into a cohesive fighting unit didn’t happen overnight. In fact, it almost didn’t happen at all.

When the squadron assembled at Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in California during August 1943, the scene was more reminiscent of a reform school than a military unit. Boington’s handpicked pilots arrived with attitudes that ranged from skeptical to openly hostile. Many had been burned by previous commanders who had promised them opportunities only to saddle them with mundane assignments or punitive duties. The first challenge was establishing credibility.

Boington knew that his reputation as a flying Tiger veteran would only carry him so far with pilots who had their own combat experience or who had heard stories about his disciplinary problems. He needed to prove that he could lead by example, not just by rank. His solution was characteristically unconventional. Instead of subjecting his pilots to traditional military discipline and rigid training schedules, Boington focused on the one thing that mattered most, learning how to kill Japanese aircraft while staying alive themselves.

Forget everything you’ve been taught about formation flying, he told his pilots during their first briefing. Forget about pretty patterns and textbook maneuvers. We’re going to learn how to fight dirty, and we’re going to learn how to win.

Boyington’s training philosophy was shaped by his experience with the Flying Tigers, where survival had depended on adapting to the enemy’s strengths while exploiting their weaknesses. He had learned that the Zer’s legendary maneuverability was also its greatest vulnerability. Japanese pilots had become so dependent on turning fights that they often ignored other tactical options.

The Corsair, with its superior speed and climb rate, was perfectly suited to exploit this weakness. But it required a completely different approach to aerial combat than what most American pilots had been taught. Hit and run, Boington explained to his pilots as they gathered around a blackboard covered with tactical diagrams. Use your speed to get in close. Take your shot and get out before they can react.

Never ever try to turn with a zero. You’ll lose every time. This was heretical thinking by 1943 standards. Most American fighter tactics still emphasized formation integrity and mutual support, concepts that worked well in theory, but often broke down in the chaos of actual combat. Boyington was advocating for something much more fluid and individualistic. But his pilots were intrigued.

These were men who had chafed under rigid military doctrine, who had been punished for thinking outside the box. Boyington was offering them permission to fight the way their instincts told them to fight. The training regimen that followed was unlike anything the Marine Corps had seen before.

Instead of practicing perfect formation flying, VMF214 pilots spent their time learning how to break formation effectively. Instead of memorizing standard attack patterns, they practiced improvisation and adaptation. Boington introduced concepts that would later become standard in American fighter tactics, but were revolutionary. In 1943, he taught his pilots about energy management, how to use altitude and speed as weapons.

He showed them how to use the Corsair’s superior diving speed to escape from dangerous situations. Most importantly, he drilled into them the importance of situational awareness and aggressive opportunism. A good pilot is always looking for an advantage, he told them. A great pilot creates his own advantages. The squadron’s unconventional training methods raised eyebrows among traditional Marine Corps officers, but the results were undeniable.

VMF214 pilots were developing a cohesion and confidence that impressed even their critics. More importantly, they were learning to think like hunters rather than soldiers. As their departure date for the Pacific approached, Boington gathered his pilots for one final briefing. The mood was different now. The skepticism and hostility had been replaced by something approaching enthusiasm.

Gentlemen, Boington said, looking around the room at the faces of men who had been written off by the system. We’re about to show the world what misfits can accomplish when they’re given a chance to prove themselves. The Japanese think they know how Americans fight. We’re going to teach them otherwise. None of them could have imagined just how prophetic those words would prove to be.

September 1943, the USS Nassau cuts through the Pacific swells, carrying VMF214 toward their destiny in the Solomon Islands. Below decks, 24 Corsair fighters are secured in the carrier’s hanger bay, their distinctive inverted gull wings folded for storage. Above decks, the Black Sheep pilots gather at the rail, watching the endless expanse of blue water that separates them from their new home.

For many of these men, this is their first glimpse of the Pacific theater, a vast oceanic battlefield where distances are measured in thousands of miles and where the nearest friendly base might be a day’s flight away. The scale is overwhelming, even for pilots accustomed to the wide open spaces of the American West. But it’s not just the geography that’s intimidating. By September 1943, the Pacific War has developed its own unique character, shaped by 2 years of brutal combat between forces that couldn’t be more different in their approach to warfare.

The Japanese have built their strategy around speed, surprise, and the spiritual superiority of their pilots. The Americans are beginning to respond with industrial might and technological innovation. Caught between these two philosophies are the islands of the Solomons, a chain of jungle-covered atals that have become the focal point of the Pacific campaign.

Names like Guadal Canal, Bugenville, and Rabul have already entered the lexicon of American military history, each representing a chapter in the bloody struggle for control of the South Pacific. VMF214’s destination is Manda airfield on New Georgia Island, a recently captured Japanese base that has been hastily converted to American use. The airfield itself tells the story of the Pacific War in miniature.

Japanese concrete bunkers and revetments now house American aircraft while hastily constructed quanset huts and tents provide accommodation for the growing number of Allied personnel. The base is a study in contrasts. American efficiency and Japanese attention to detail create an odd hybrid that somehow manages to function despite its improvised nature.

The runway, originally built by Japanese engineers using forced labor, is now extended and improved by American CBS working around the clock to accommodate the growing number of Allied aircraft. When VMF 214 finally arrives at Mund in midepptember, they are greeted by a scene that perfectly captures the organized chaos of the Pacific theater.

The airfield is buzzing with activity as ground crews service aircraft, supply trucks navigate muddy roads, and pilots from various squadrons prepare for missions that will take them deep into Japanese controlled territory. But there’s something else in the air at Manda. Attention that speaks to the deadly serious nature of the work being done here. This isn’t a training base or a rear area facility.

This is the front line of the Pacific War, and everyone here knows that their next mission might be their last. The squadron’s first briefing takes place in a sweltering Quonet hut that serves as the intelligence center. Maps cover every available wall surface, showing the complex geography of the Solomons and the disposition of Japanese forces throughout the region.

Red pins mark known enemy airfields, while blue pins indicate Allied positions. The pattern tells a story of gradual Allied advance, but also of stubborn Japanese resistance. Gentlemen, the intelligence officer begins, pointing to a large map of the central Solomons.

Welcome to the most active piece of real estate in the Pacific. Every day we’re flying missions against Japanese positions throughout this region. Every day they’re trying to stop us. The statistics he presents are sobering. Japanese fighter strength in the region is estimated at over 200 aircraft, most of them based at the massive complex at Rabul on New Britain Island. These aren’t the green pilots that American forces are beginning to encounter in other theaters.

Many of these men are veterans with years of combat experience. The good news, the briefing officer continues, is that we’re finally getting aircraft that can match their performance. The bad news is that they still know how to use their aircraft better than most of our pilots know how to use ours.

It’s a blunt assessment that captures the reality of the Pacific Air War in late 1943. American industry has finally produced fighters capable of challenging Japanese superiority, but the learning curve remains steep. Too many American pilots are still dying while they figure out how to fight effectively against an enemy that has been perfecting their tactics for years.

As the briefing continues, Boington studies the faces of his pilots. These men have trained hard and prepared well, but training is one thing, and combat is another. In a few days, they’ll be flying their first missions over enemy territory, and all their preparation will be put to the ultimate test. The squadron’s first assignment is relatively straightforward.

escort duty for bombing missions against Japanese positions on Bugenville Island. It’s the kind of mission that allows new pilots to ease into combat operations while providing valuable experience in formation, flying, and navigation over enemy territory. But Boington has other plans. As he studies the mission briefings and intelligence reports, he begins to formulate a strategy that will play to his squadron’s strengths while exploiting what he sees as fundamental weaknesses in Japanese tactical doctrine. We’re not going to fly like everyone else, he tells his pilots during their first squadron meeting at

Munda. We’re going to hunt. October 1st, 1943. The morning sun casts long shadows across Mund airfield as VMF214 prepares for their first combat mission. The air is thick with humidity and the smell of aviation fuel as ground crews make final preparations on 24 Corsair fighters.

For the Black Sheep pilots, this moment represents the culmination of months of training and preparation. But it also marks the beginning of something none of them can fully anticipate. A campaign that will redefine American fighter tactics and leave Japanese pilots questioning everything they thought they knew about aerial combat. The mission briefing is routine by Pacific theater standards.

escort a formation of SBD Dauntless dive bombers on a strike against Japanese positions on Bal Island, a small airfield in the southern Solomons that serves as a forward base for zero fighters. Intelligence reports suggest moderate enemy fighter opposition, perhaps a dozen zeros based at the target with the possibility of reinforcements from larger bases to the north.

As Boington studies the mission parameters, he sees an opportunity to implement the unconventional tactics he’s been developing. Instead of maintaining tight formation with the bombers, the standard escort procedure, he plans to use VMF214 as a roving patrol hunting for Japanese fighters while the bombers complete their attack. We’re going to split into four plane divisions, he explains to his pilots as they gather around a makeshift briefing board.

Each division will operate independently, looking for targets of opportunity. Stay flexible, stay aggressive, and remember, speed is life. It’s a radical departure from standard escort doctrine, which emphasizes formation integrity and close support for the bombers. But Boyington’s experience with the flying tigers has taught him that rigid adherence to doctrine often leads to missed opportunities and unnecessary casualties.

At dro 800 hours, the formation takes off from Munda. 12 SBD dauntlesses followed by 24 corsairs in loose formation. The flight north toward Bal takes them over some of the most beautiful and deadly territory in the Pacific. Emerald Islands surrounded by coral reefs. Their jungle covered hills hiding Japanese positions that could erupt with anti-aircraft fire at any moment.

For the newer pilots in VMF 214, this first glimpse of the combat zone is both exhilarating and sobering. The islands below look peaceful from altitude, but everyone knows that appearances can be deceiving in the Solomons. Japanese forces have had months to prepare defensive positions, and they’ve proven remarkably adept at concealing their strength until the moment of attack.

As the formation approaches Balal, Boington begins implementing his tactical plan. Instead of maintaining close formation with the bombers, he leads his corsair in a wide sweep around the target area, looking for Japanese fighters that might be climbing to intercept the attack. The response comes sooner than expected. At AU 845 hours, as the Dauntlesses begin their bombing runs, a formation of 8 fighters appears from the direction of Cahili airfield on Bugenville.

They’re climbing hard, trying to gain altitude advantage before engaging the American formation. For the Japanese pilots, this appears to be a routine interception, the kind of mission they’ve flown dozens of times before. American bombers protected by fighters flying predictable escort patterns, vulnerable to coordinated attacks by experienced zero pilots who know how to exploit their aircraft’s superior maneuverability.

But VMF214 isn’t flying predictable patterns. As the Zeros climb toward the bombers, they find themselves facing something they’ve never encountered before. American fighters that are hunting them rather than simply defending their charges. Boyington spots the climbing zeros first and immediately radios his division leaders. Bandits 2:00 high. All divisions attack at will.

What happens next will be talked about in Japanese pilot ready rooms for months to come. Instead of maintaining formation and waiting for the Zeros to attack, the Corsair’s immediately split into their pre-planned divisions and begin a coordinated assault that catches the Japanese pilots completely offguard. The lead zero pilot, a veteran with over 50 combat missions, suddenly finds himself facing not one or two American fighters, but an entire division of Corsair’s diving on his formation from multiple angles. His training tells him to turn into the attack using his aircraft’s superior maneuverability to

force the Americans into a turning fight where the Zer’s advantages would become apparent. But the Corsair’s don’t cooperate. Instead of accepting the turning fight, they use their superior speed to slash through the Zero formation, firing quick bursts before climbing away to set up for another attack.

It’s a tactic that plays to the Corsair’s strengths while negating the Zero’s primary advantage. The Japanese pilot finds himself in an impossible situation. Every time he turns to engage one Corsair, another appears from a different angle. The Americans are using their speed and teamwork to create multiple threats simultaneously, forcing the Zeros to react rather than dictate the terms of the engagement. Within minutes, three Zeros are falling toward the ocean below.

Their pilots either dead or struggling with damaged aircraft. The remaining Japanese fighters faced with an enemy that refuses to fight according to established doctrine break off the engagement and flee toward their home base. For VMF214, it’s a stunning debut. Three confirmed kills with no losses, a result that exceeds even Boington’s optimistic expectations.

But more importantly, they’ve demonstrated the effectiveness of tactics that will soon revolutionize American fighter operations throughout the Pacific. As the Corsair’s reform and head back toward Manda, Boyington can’t help but smile. His misfits have just announced their arrival in the Pacific theater in spectacular fashion. But this is only the beginning.

The intelligence reports that reached Japanese headquarters at Rabul that evening painted a disturbing picture. Eight experienced zero pilots had engaged what appeared to be a routine American escort mission only to find themselves facing tactics they had never encountered before. Three aircraft had been lost, and the surviving pilots described American fighters that seemed to operate with a level of coordination and aggressiveness that defied conventional understanding.

Lieutenant Commander Masajiro Kawato, one of the most experienced fighter leaders in the Japanese Navy, read the reports with growing concern. Kawato was a veteran of the China war and had been flying combat missions since the attack on Pearl Harbor. He had seen American fighter tactics evolve over 2 years of warfare. But what the Balal survivors described was something entirely different.

They didn’t fight like Americans, one of the surviving pilots reported during his debriefing. They fought like like us but with better aircraft. It was a telling observation. For two years, Japanese pilots had grown accustomed to American fighters that operated according to predictable patterns. American formations were typically tight and defensive, focused on protecting bombers rather than hunting enemy fighters.

When American pilots did engage, they usually tried to use their aircraft’s advantages in ways that Japanese pilots could anticipate and counter. But VMF214 had demonstrated something different. A fluid, aggressive approach that seemed to combine the best elements of Japanese tactical flexibility with superior American aircraft performance.

It was a combination that Japanese commanders found deeply troubling. The concern was not limited to tactical considerations. By October 1943, Japanese aviation was facing a crisis that went far beyond individual battles or even specific campaigns. The industrial war of attrition that American planners had always envisioned was finally beginning to take its toll on Japanese capabilities.

Aircraft production, while still substantial, was beginning to fall behind the pace of losses. More critically, the pool of experienced pilots that had given Japanese aviation its early dominance was being steadily depleted. The men who had trained for years before the war, who had honed their skills in China and perfected their techniques in the early Pacific campaigns were irreplaceable.

Every experienced pilot lost to enemy action represented not just a tactical setback, but a strategic catastrophe. The Japanese training system designed for peacetime conditions simply could not produce replacement pilots at the rate they were being consumed by combat operations. This reality gave special significance to encounters like the one at Balala.

If American pilots were developing tactics that could consistently defeat experienced Japanese aviators, the implications for the broader war effort were ominous indeed. Word of VMF214’s success spread quickly through allied intelligence networks as well. Within days of the Bal mission, reports of the black sheep’s unconventional tactics were being analyzed by planners throughout the Pacific theater.

Here finally was evidence that American pilots could not only match Japanese performance, but potentially exceed it. The key, analysts realized, was not just superior aircraft, though the Corsair’s performance advantages were certainly important, but superior tactics. VMF214 had demonstrated that American pilots could be just as flexible and aggressive as their Japanese counterparts when freed from rigid doctrinal constraints.

But it was the psychological impact that proved most significant for Japanese pilots throughout the Solomons. The Balal engagement represented something more troubling than a tactical defeat. It suggested that the Americans were learning, adapting, and evolving their approach to aerial combat in ways that threatened the fundamental assumptions upon which Japanese air strategy was based.

The myth of Japanese invincibility, already weakened by two years of increasingly costly battles, was beginning to crack, and VMF214 was just getting started. As October progressed, the Black Sheep continued their aggressive patrol operations, racking up victories at a rate that astonished both their allies and their enemies.

Each engagement seemed to validate Boington’s unconventional approach while demonstrating to Japanese pilots that the rules of aerial combat in the Pacific were changing. But the real test was yet to come. Intelligence reports indicated that Japanese commanders were beginning to take special notice of VMF21’s activities. Plans were being made to deal with this troublesome American squadron.

plans that would bring the Black Sheep face to face with some of the most experienced and dangerous pilots in the Japanese Navy. The stage was being set for a confrontation that would determine not just the fate of individual pilots, but the future of aerial warfare in the Pacific.

And at the center of it all was a squadron of misfits who had found their calling in the deadly skies above the Solomon Islands. By the end of October 1943, VMF214 had established itself as one of the most effective fighter squadrons in the Pacific theater. In just 4 weeks of combat operations, they had shot down 23 Japanese aircraft while losing only three of their own, a kill ratio that exceeded even the most optimistic projections.

But statistics, impressive as they were, told only part of the story. The real significance of the black sheep’s early success lay in what it represented. Proof that American pilots could not only match Japanese performance, but potentially surpass it when given the right aircraft, the right tactics, and the right leadership.

For Boyington and his misfits, these early victories represented vindication of everything they had worked toward. Men who had been written off by the system, pilots whose careers had seemed destined for mediocrity or failure, were proving that unconventional thinking could produce extraordinary results.

But they were also attracting attention from quarters they might have preferred to avoid. Japanese intelligence had identified VMF214 as a priority target, and plans were already in motion to deal with what Tokyo was beginning to regard as a serious threat to Japanese air superiority in the Solomons. The squadron’s success had also created expectations that would be difficult to maintain.

Allied commanders, impressed by the black sheep’s early performance, were beginning to assign them increasingly dangerous missions. The relatively routine escort duties of their first weeks were giving way to long range fighter sweeps deep into Japanese controlled territory. As November approached, Boington could sense that the easy victories were coming to an end.

Japanese pilots were adapting to VMF214’s tactics, developing counter measures that threatened to neutralize the squadron’s advantages. More ominously, intelligence reports suggested that elite Japanese fighter units were being redeployed to the Solomon specifically to deal with the black sheep threat. The stage was being set for a confrontation that would test everything VMF214 had learned about aerial combat.

In the weeks to come, they would face not just individual Japanese pilots, but coordinated efforts by some of the most experienced and dangerous aviators in the Imperial Navy. The question was whether a squadron of misfits, no matter how skilled or determined, could maintain their edge against an enemy that was learning to fight back with equal determination and superior numbers.

The answer would determine not just the fate of VMF 214, but the future of American fighter operations throughout the Pacific theater. And as the November sun set over Manda airfield, casting long shadows across the coral runway, both sides prepared for a battle that would push the limits of human courage and flying skill. The Black Sheep had announced their arrival in spectacular fashion.

Now they would have to prove they could survive the storm they had helped to create. November 1943. Deep within the volcanic tunnels of Rabul, the largest Japanese air base in the South Pacific, a crisis meeting was taking place that would reshape the aerial war over the Solomons. The underground command center, carved from solid rock to protect against Allied bombing raids, buzzed with urgent activity as intelligence officers spread reconnaissance photos and combat reports across planning tables.

At the center of the discussion was a single American fighter squadron that had in just 6 weeks fundamentally altered the balance of power in the region’s skies. VMF21 Horn’s success rate was not just statistically impressive. It was strategically threatening. More concerning still were the reports filtering in from surviving Japanese pilots, descriptions of American tactics that seemed to violate every principle of aerial combat that Japanese aviators had been taught.

Captain Tetsuzo Iwamoto, one of Japan’s leading fighter aces with over 80 confirmed victories, studied the intelligence reports with growing unease. Iwamoto had been flying combat missions since the China War and had personally shot down more American aircraft than any other pilot in the region. But the reports he was reading described something he had never encountered before.

They fight like a pack of wolves, one surviving Zero pilot had reported after a disastrous encounter with the black sheep over Bugenville. No formation, no discipline, but perfect coordination. It’s as if they can read each other’s minds. Another pilot, a veteran with over 40 missions, described tactics that seemed almost supernatural in their effectiveness.

They appear from nowhere, strike like lightning, and vanish before we can respond. Our aircraft are superior in turning ability, but they refuse to turn with us. They fight only when they have the advantage, and they always seem to have the advantage. For Japanese commanders accustomed to American pilots who fought according to predictable patterns, these reports were deeply disturbing. VMF214 represented something new and dangerous.

American pilots who had learned to think like Japanese pilots while retaining the technological advantages of superior aircraft. The response was swift and comprehensive. Within days of the November planning conference, Japanese aviation units throughout the region received new tactical directives specifically designed to counter the black sheep threat.

Elite fighter squadrons were redeployed from other theaters, bringing with them pilots whose experience and skill matched anything the Americans could field. But perhaps most significantly, Japanese commanders made a decision that would have far-reaching consequences for the Pacific Air War. They authorized the deployment of their most experienced and dangerous pilots, specifically to hunt down and destroy VMF 214.

Among these elite aviators was Lieutenant Hiroyoshi Nishawa, perhaps the most skilled fighter pilot in the Japanese Navy. Known to his fellow pilots as the devil, Nishawa had over 100 confirmed victories and a reputation for aerial combat skills that bordered on the mythical. His assignment was simple. Find the Black Sheep Squadron and destroy it.

The stage was being set for a confrontation between two fundamentally different approaches to aerial warfare. On one side, a squadron of American misfits who had learned to fight with improvisation and aggressive opportunism. On the other, the cream of Japanese naval aviation, pilots whose skills had been honed through years of training and combat experience.

The first sign that the rules of engagement were changing came on November 11th, 1943. VMF214 was flying a routine fighter sweep over Buganville when they encountered something they had never seen before. A formation of Japanese fighters that seem to anticipate their every move. The engagement began typically enough.

Boyington led his 24 corsairs in a wide sweep around Japanese positions, looking for targets of opportunity. Intelligence had reported moderate enemy fighter activity in the area. perhaps a dozen zeros based at Cahili airfield. What they found instead was a carefully orchestrated trap. As the black sheep approached what appeared to be a small formation of Japanese fighters, additional enemy aircraft began appearing from multiple directions.

These weren’t the random encounters that had characterized earlier missions. This was a coordinated effort by experienced pilots who had studied VMF 214’s tactics and developed specific counter measures. Bandits everywhere came the urgent radio call from one of Boington’s wingmen. They’re coming from all directions. For the first time since arriving in the Pacific, VMF 214 found themselves facing an enemy that seemed to understand their tactics as well as they did.

The Japanese pilots were using the Corsair’s own aggressive tendencies against them, drawing them into situations where superior numbers could negate the Americans technological advantages. The battle that followed was unlike anything the Black Sheep had experienced. Instead of the quick decisive engagements that had characterized their early success, they found themselves locked in a prolonged dog fight with pilots whose skills matched their own.

Lieutenant Hiroshi Nishawa, leading the Japanese formation, demonstrated why he was considered one of the most dangerous pilots in the Pacific. Flying a specially modified Zero with enhanced engine performance, he seemed to anticipate the Corsair’s attacks before they developed, positioning himself to exploit every tactical mistake.

This guy’s different, Boington radioed to his pilots as he found himself in a turning fight with Nishawa Zero. He knows what we’re going to do before we do it. It was an accurate assessment. Nishawa had spent weeks studying intelligence reports on VMF 2114’s tactics, learning to think like Boyington and his pilots.

More importantly, he had trained his own pilots to work as a coordinated unit specifically designed to counter the black sheep’s advantages. The engagement lasted nearly 30 minutes, an eternity in aerial combat terms. When it finally ended, both sides had paid a heavy price. VMF 214 lost four Corsaires, their heaviest losses since arriving in the Pacific. But the Japanese losses were even more severe.

Seven zeros destroyed, including several flown by experienced pilots whose deaths represented irreplaceable losses to Japanese aviation. As the surviving aircraft limped back to their respective bases, both sides realized that the nature of the air war over the Solomons had fundamentally changed. The easy victories were over.

From now on, every engagement would be a test of skill, courage, and determination between pilots who represented the best their respective nations could field. The escalating intensity of aerial combat over the Solomons was taking a toll that went far beyond simple statistics. For the pilots of VMF214, the psychological pressure of sustained combat operations was beginning to show in ways that their unconventional training had never prepared them for.

Staff Sergeant Henry Miller, one of the squadron’s most reliable pilots, began experiencing what would later be recognized as combat fatigue. After his 15th mission, he found himself unable to sleep, haunted by images of burning aircraft and falling pilots. The easy camaraderie that had characterized the squadron’s early days was giving way to a grim professionalism that spoke to the deadly, serious nature of their work.

We’re not the same guys who left California, Miller confided to his tentmate after a particularly brutal mission over Rabul. Something’s changed in all of us. It was an observation that applied to both sides of the conflict. Japanese pilots facing increasingly sophisticated American tactics and superior aircraft were struggling with their own psychological demons.

The myth of Japanese invincibility, so carefully cultivated during the early years of the Pacific War, was crumbling under the weight of mounting losses and diminishing resources. For pilots like Lieutenant Nishawa, the pressure was particularly intense. As one of Japan’s most celebrated aces, he carried the expectations of an entire nation on his shoulders.

Every mission was not just a tactical engagement, but a test of Japanese marshall spirit against American industrial might. The human drama playing out in the skies above the Solomons was reflected in the personal stories of individual pilots on both sides. Captain Stan Bailey, one of VMF214’s original members, shot down his 10th Japanese aircraft on November 18th, making him an ace twice over.

But the victory celebration was muted by the knowledge that each success brought them closer to the inevitable moment when their luck would run out. Japanese pilots faced an even grimmer reality. Unlike their American counterparts who could expect to be rotated home after completing a tour of duty, Japanese aviators flew until they were killed, wounded, or the war ended.

The psychological pressure of knowing that every mission might be their last created a fatalistic mindset that affected their tactical decision-making. This human dimension of the air war was perhaps best illustrated by an incident that occurred on November 20th, 1943. During a fierce dog fight over Bugganville, VMF214 pilot Bob McCur found himself in a turning fight with a Japanese Zero whose pilot demonstrated exceptional skill and determination.

For nearly 10 minutes, the two aircraft circled each other in a deadly dance. Each pilot looking for the split-second advantage that would determine the outcome. Mcclur, flying a Corsair that should have had significant performance advantages, found himself matched by a Japanese pilot whose flying skills were nothing short of extraordinary.

The engagement ended when Mcclur’s aircraft suffered engine damage from ground fire, forcing him to break off the fight and head for home. As he climbed away from the battle, he caught a glimpse of the zero pilot in his cockpit. A young man who couldn’t have been more than 20 years old, but whose eyes held the thousand-y stare of someone who had seen too much combat. He was just a kid, Mcclur reported during his debriefing.

But he flew like he’d been doing it his whole life. Makes you wonder what kind of training they put these guys through. to do. It was a question that spoke to one of the fundamental differences between Japanese and American approaches to aviation training.

While American pilots received excellent technical instruction and adequate flight time, Japanese pilots underwent years of intensive preparation that bordered on the obsessive. The result was a generation of aviators whose flying skills were extraordinary, but whose numbers were finite and irreplaceable. December 17th, 1943.

The date would be remembered as one of the most significant in the history of Pacific air warfare, though few participants realized its importance at the time. For VMF214, it began as a routine fighter sweep over Rabul, the kind of mission they had flown dozens of times before. For the Japanese defenders, it represented an opportunity to deal a decisive blow to the troublesome American squadron that had been disrupting their operations for months.

The mission briefing at Mund had been straightforward. escort a formation of B-25 Mitchell bombers on a strike against Japanese shipping in Simpson Harbor, then conduct a fighter sweep over the Rabal complex to suppress enemy air activity. Intelligence estimated moderate fighter opposition, perhaps 20 to 30 zeros based at the various airfields around Rabal.

What intelligence had failed to detect was the largest concentration of Japanese fighter aircraft assembled in the South Pacific since the early days of the war. Over 100 fighters drawn from elite units throughout the region were waiting for VMF 2114’s arrival.

The trap was sprung as the American formation approached the target area. As the B-25s began their bombing runs, wave after wave of Japanese fighters appeared from multiple directions, climbing hard to intercept the American formation. It was immediately clear that this was no routine engagement. The Japanese had committed everything they had to destroying the Black Sheep squadron.

Jesus Christ, came the stunned radio transmission from one of Boington’s pilots. There must be a hundred of them. For a moment that seemed to stretch into eternity, the sky above Rabal was filled with aircraft locked in the largest aerial battle of the Pacific War to date. Corsair’s and zeros twisted and turned in a three-dimensional chess match where the stakes were measured in human lives.

Boyington, leading his pilots into the maelstrom, quickly realized that conventional tactics would be suicide against such overwhelming numbers. Instead, he made a decision that would become legendary in Marine Corps aviation history. Rather than trying to maintain formation integrity, he ordered his pilots to break into two plane elements and fight as individual hunting teams. All black sheep, this is Papy, he radioed to his scattered pilots.

Break into sections and hunt. Use your speed, use your climb rate, and don’t get trapped in turning fights. We’re going to show these bastards what American pilots can do when they’re really pissed off. What followed was perhaps the most extraordinary display of aerial combat skill in the history of warfare.

24 American pilots outnumbered more than 4 to one took on the cream of Japanese naval aviation in a battle that would be talked about for decades to come. The key to VMF214 survival was their ability to adapt their tactics to the situation. Instead of trying to engage every Japanese fighter they encountered, they focused on creating local superiority through superior coordination and communication.

Two plane elements would work together to isolate individual Japanese fighters, using their aircraft’s performance advantages to dictate the terms of each engagement. Lieutenant Nishawa, leading the Japanese effort, found himself facing an enemy that seemed to have evolved beyond his ability to predict or counter.

Every time he positioned his fighters to exploit what appeared to be American tactical mistakes, the Corsaires would adapt and respond with moves he hadn’t anticipated. “They are not fighting like Americans anymore,” he radioed to his wingman during the height of the battle. “They’re fighting like I don’t know what they’re fighting like.

” It was a telling observation. VMF214 had indeed evolved beyond conventional American fighter tactics, developing an approach to aerial combat that combined the best elements of Japanese flexibility with American technological superiority. They were no longer simply American pilots flying American aircraft. They had become something new and uniquely dangerous.

The battle raged for over an hour with individual engagements breaking out across hundreds of square miles of airspace. When it finally ended, the statistics were staggering. VMF214 had shot down 26 Japanese aircraft while losing only six of their own. But more importantly, they had broken the back of Japanese fighter resistance in the Solomons.

Among the Japanese losses was Lieutenant Nishazawa himself, shot down by Boington in a head-to-head engagement that lasted less than 30 seconds, but represented the culmination of months of tactical evolution on both sides. As the surviving aircraft limped back to their respective bases, both sides realized that something fundamental had changed in the Pacific Air War.

The Japanese had committed their best pilots and aircraft to destroying VMF 214 and they had failed decisively. The psychological impact of that failure would resonate throughout Japanese aviation for the remainder of the war. The Battle of Rabbal, as it came to be known in American aviation circles, marked the end of Japanese air superiority in the South Pacific.

More than just a tactical victory, it represented a fundamental shift in the balance of power that would influence the course of the Pacific War for years to come. For VMF24, the victory came at a significant cost. Six pilots lost in a single engagement represented their heaviest casualties since arriving in the Pacific, and the psychological toll on the survivors was evident.

The easy confidence that had characterized their early missions was replaced by a grim professionalism that spoke to the deadly serious nature of their work. But the squadron’s reputation was now secure. Word of their victory over overwhelming odds spread throughout the Pacific theater, inspiring other American fighter units to adopt similar tactics. The rigid formation flying and defensive mindset that had characterized early American fighter operations gave way to a more flexible, aggressive approach that played to American technological advantages.

Japanese aviation, meanwhile, was beginning to show signs of the attrition that would eventually their effectiveness. The loss of experienced pilots like Nishawa represented not just tactical setbacks but strategic catastrophes. The Japanese training system designed for peaceime conditions simply could not replace such losses at the rate they were being incurred.

By January 1944, VMF214 had completed their tour of duty and was scheduled to return to the United States. Their final statistics were impressive by any measure. 97 confirmed aerial victories against 20 losses. A kill ratio that exceeded even the most optimistic projections. But their real contribution to the war effort went far beyond simple numbers.

They had demonstrated that American pilots, when properly trained and equipped, could not only match Japanese performance, but exceed it. More importantly, they had developed tactical innovations that would become standard throughout American aviation, influencing fighter operations for decades to come. The human cost of their success was evident in the faces of the men who gathered for their final squadron photograph at Munda Airfield. These were not the same pilots who had left California 6 months earlier. Combat had aged them in ways

that went far beyond simple chronology, marking them with the thousand-yd stare that characterized veterans of sustained aerial combat. For Boington himself, the end of the tour marked both triumph and tragedy. His personal score of 28 confirmed victories made him one of the leading American aces of the war.

But his methods had also earned him enemies within the military establishment who viewed his unconventional approach with suspicion. More troubling still were the signs of combat fatigue that were becoming increasingly evident in his behavior. The drinking that had always been a problem was becoming more serious, and his relationships with superior officers were deteriorating rapidly.

The same independence and disregard for authority that had made him an effective combat leader were becoming liabilities in peaceime military service. To truly understand the impact of VMF214 success, it’s essential to examine the war from the Japanese perspective. For pilots who had dominated Pacific skies for two years, the emergence of American squadrons capable of consistently defeating experienced Japanese aviators, represented a psychological shock that went far beyond tactical considerations.

Captain Saburo Sakai, one of Japan’s most celebrated aces, later wrote about the impact of encounters with squadrons like VMF214. We had been taught that American pilots were inferior, that they lacked the spiritual strength necessary for aerial combat.

But these new Americans fought with the determination and skill that matched our own. Worse, they had aircraft that were superior to ours in almost every respect. The technological gap was indeed becoming decisive. While the Zero had been a revolutionary aircraft in 1940, by 1943 it was being outclassed by newer American fighters like the Corsair and Hellcat.

Japanese industry struggling under the pressure of Allied bombing and resource shortages was unable to develop effective replacements at the pace required by combat operations. But perhaps more damaging than technological inferiority was the psychological impact of sustained defeats. Japanese pilots who had grown accustomed to victory were suddenly finding themselves consistently outfought by an enemy they had been taught to despise.

The spiritual superiority that had been central to Japanese military doctrine was being challenged by the harsh realities of modern warfare. Lieutenant Yasuhiko Kuro, a zero pilot who survived multiple encounters with VMF214, described the psychological impact in his postwar memoirs. We began to doubt everything we had been taught about American pilots.

If they could fight like this, what else had we been wrong about? The certainty that had sustained us through the early years of the war was crumbling. This erosion of confidence had tactical implications that went far beyond individual engagements. Japanese pilots who had once pressed attacks with suicidal determination began showing signs of hesitation and caution.

Formation discipline, once the hallmark of Japanese aviation, began to break down as pilots became more concerned with individual survival than unit effectiveness. The impact was particularly severe among newer pilots who lacked the combat experience of veterans like Nishiawa and Sakai. These men, hastily trained to replace mounting losses, found themselves facing American pilots whose skills and confidence seemed to grow with each engagement.

By early 1944, Japanese aviation in the South Pacific was in full retreat. The bases that had once launched daily raids against Allied positions were being abandoned or reduced to defensive operations. The initiative in the air war had passed decisively to the Americans and it would never return. The success of VMF 214 had implications that extended far beyond the Solomon Islands campaign.

Throughout the Pacific theater, American fighter squadrons began adopting the flexible, aggressive tactics that Boyington had pioneered with his Black Sheep. The rigid formation flying that had characterized early American fighter operations gave way to a more fluid approach that emphasized individual initiative within a framework of mutual support. Pilots were encouraged to think like hunters rather than soldiers, to look for opportunities rather than simply follow orders.

This tactical evolution was facilitated by improvements in aircraft performance and pilot training. The Corsair and Hellcat fighters that began reaching the Pacific in large numbers during 1943 were not only superior to Japanese aircraft in most performance categories, but they were also more forgiving of pilot errors and more capable of sustaining battle damage.

Perhaps more importantly, American pilot training was beginning to emphasize the kind of flexible thinking that had made VMF214 so effective. Instead of teaching rigid adherence to doctrine, instructors began encouraging students to adapt their tactics to specific situations and to think creatively about how to exploit their aircraft’s advantages.

The results were evident in the kill ratios achieved by American fighter squadrons throughout 1944. Where early war engagements had often favored Japanese pilots, American squadrons were now routinely achieving kill ratios of 3 or 4:1 against experienced Japanese opposition. This tactical evolution was not lost on Japanese observers.

Intelligence reports from late 1943 and early 1944 repeatedly noted the improved quality of American fighter operations and the increasing difficulty of achieving successful interceptions against Allied formations. But by then it was too late for Japanese aviation to adapt effectively. The loss of experienced pilots and the degradation of training standards meant that Japanese squadrons were increasingly filled with hastily trained replacements who lacked the skills necessary to compete with improving American pilots. The tactical innovations pioneered by VMF214

had become standard throughout American aviation, creating a generation of fighter pilots whose skills and confidence would prove decisive in the final years of the Pacific War. As VMF214 prepared for their final missions in the Pacific, the character of the air war had changed dramatically from their early days of easy victories and overwhelming success.

Japanese resistance, while weakened, had become more desperate and unpredictable. Pilots who knew they were unlikely to survive the war, fought with a fatalistic determination that made them extremely dangerous opponents. The squadron’s last major engagement took place on January 3rd, 1944 during a fighter sweep over Rabul.

By this time, Japanese air strength in the region had been reduced to fewer than 50 operational aircraft, but these were flown by the most experienced and determined pilots remaining in the theater. The engagement began when VMF214 encountered a formation of 12 zero fighters attempting to intercept a group of Allied bombers.

What should have been a routine engagement quickly developed into a fierce dog fight as the Japanese pilots, knowing this might be their last opportunity to strike a blow against the hated black sheep, pressed their attacks with suicidal determination. The battle was notable not for its scale. Only 36 aircraft were involved, but for its intensity.

Japanese pilots, who might normally have broken off when faced with superior numbers, instead chose to fight to the death, turning the engagement into a series of individual duels between pilots who represented the best their respective nations could field. When the smoke cleared, VMF214 had achieved another tactical victory, shooting down eight Japanese aircraft while losing three of their own. But the cost of victory was becoming increasingly apparent.

The pilots who returned to Manda that evening were exhausted both physically and emotionally by months of sustained combat operations. For Boington, the engagement marked the end of an extraordinary combat career. His personal score now stood at 28 confirmed victories, making him one of the leading American aces of the war, but the toll of sustained combat was evident in his haggarded appearance and increasingly erratic behavior.

3 days later, on January 6th, 1944, Boyington was shot down during a mission over Rabal and captured by Japanese forces. His loss marked the effective end of VMF214’s combat operations, though the squadron would continue flying missions under new leadership until their scheduled rotation home.

The story of VMF214 represents more than just the tale of a successful fighter squadron. It illustrates the broader transformation of American military aviation during World War II from a force that struggled to match Japanese performance in 1942 to one that achieved decisive superiority by 1944.

The tactical innovations pioneered by Boyington and his Black Sheep became standard throughout American fighter aviation, influencing operations not just in the Pacific, but in Europe as well. The flexible, aggressive approach they developed proved adaptable to different aircraft types and operational environments, providing a template for effective fighter operations that remained relevant long after the war ended.

Perhaps more importantly, VMF 214 demonstrated that unconventional thinking and leadership could produce extraordinary results when applied to military problems. Boyington’s willingness to challenge established doctrine and his ability to inspire misfits and rejects to perform at the highest levels provided lessons that extended far beyond aviation. The human cost of their success was significant.

Of the original 24 pilots who deployed with VMF214 in September 1943, only 14 returned home at the end of their tour. The others were killed in action, missing in action, or too badly wounded to continue flying. It was a casualty rate that reflected the deadly nature of aerial combat in the Pacific theater.

For the Japanese pilots who faced them, VMF214 represented something more troubling than just another enemy squadron. They embodied the evolution of American military capability from amateur to professional, from reactive to proactive, from defensive to aggressively offensive. The psychological impact of consistently losing to pilots they had been taught to regard as inferior was devastating to Japanese morale and confidence.

The broader strategic impact of squadrons like VMF214 was decisive in the outcome of the Pacific War. By achieving air superiority over Japanese forces, American aviation made possible the amphibious operations that would eventually bring Allied forces to the Japanese home islands. Without control of the skies, the island hopping campaign that characterized American strategy in the Pacific would have been impossible.

Today, more than 80 years after VMF 214 first took to the skies over the Solomon Islands, their story continues to resonate with new generations of military aviators and historians. The squadron’s success represents a unique moment in military history when individual initiative and unconventional thinking could still make a decisive difference in the outcome of major conflicts.

The men who flew with the black sheep went on to varied post-war careers, but they were forever marked by their experience in the Pacific. Some, like Stan Bailey and Bob McClur, continued flying with the Marines, eventually retiring as senior officers. Others left military service to pursue civilian careers, carrying with them the confidence and leadership skills they had developed during their time with VMF214.

Boington himself survived Japanese captivity and returned home to a hero’s welcome, eventually receiving the Medal of Honor for his service with VMF214. But his post-war years were marked by the same personal struggles that had characterized his pre-war career. The independence and disregard for authority that had made him an effective combat leader proved difficult to channel in peaceime pursuits.

The Japanese pilots who survived encounters with VMF214 carried their own memories of the squadron’s impact. Many later wrote about the psychological shock of facing American pilots who seemed to have learned to fight with Japanese-style flexibility and aggression while retaining the technological advantages of superior aircraft. For military historians, the story of VMF214 provides valuable insights into the nature of tactical innovation and the importance of adaptive leadership in combat situations.

Their success demonstrates that even in highly technological warfare, human factors like creativity, determination, and effective leadership remain decisive. The legacy of the Black Sheep Squadron extends beyond their immediate impact on the Pacific War. They helped establish principles of fighter tactics that remained relevant through the jet age and into the modern era of air combat.

Their emphasis on flexibility, aggression, and individual initiative within a framework of mutual support became hallmarks of American fighter doctrine. Perhaps most importantly, they proved that unconventional approaches to military problems could produce extraordinary results when applied by skilled and determined individuals.

In an age of increasingly complex military technology and doctrine, the story of VMF214 serves as a reminder that human creativity and leadership remain the most important factors in military success. The skies over the Solomon Islands are peaceful now, marked only by the occasional commercial airliner carrying tourists to visit the battlefields where the fate of the Pacific was decided.

But for those who know the history, it’s impossible to look up at those blue expanses without imagining the drama that once played out there. The deadly dance of Corsaires and Zeros, the radio chatter of pilots locked in mortal combat, and the courage of men who risked everything to prove that misfits could indeed rule the skies.

The Black Sheep Squadron’s story reminds us that in The Crucible of Combat, it’s not always the most conventional or well-behaved who prove most effective. Sometimes it takes misfits, rebels, and troublemakers to find new ways of solving old problems. And sometimes those solutions can change the course of history itself. In the end, that may be the most important legacy of VMF214, the demonstration that in the right circumstances, with the right leadership, and given the right opportunity, even the most unlikely heroes can achieve the impossible.

It’s a lesson that remains as relevant today as it was in the skies over the Pacific more than eight decades ago. As we close this remarkable chapter in aviation history, it’s worth reflecting on what made VMF 214 so extraordinary. They were not superhuman.

They were simply ordinary men who found themselves in extraordinary circumstances and rose to meet the challenge with courage, creativity, and determination. Their story serves as a testament to the power of unconventional thinking and effective leadership. Boyington’s willingness to challenge established doctrine and his ability to inspire his pilots to perform beyond their perceived limitations created a force that was greater than the sum of its parts.

But perhaps most importantly, the Black Sheep Squadron’s legacy reminds us that in the darkest moments of human conflict, individual courage and determination can still make a decisive difference. In an age when warfare seems increasingly dominated by technology and industrial capacity, their story provides hope that human factors, creativity, leadership, and the willingness to sacrifice for something greater than oneself remain the ultimate arbittors of victory and defeat. The Japanese pilots, who couldn’t believe what they were seeing when VMF214

came to rule the skies, were witnessing more than just superior tactics or better aircraft. They were seeing the emergence of a new kind of American military capability, one that combined technological superiority with tactical innovation and inspired leadership. That combination would prove decisive not just in the Pacific War, but in the broader struggle between democratic and authoritarian systems that defined the 20th century.

The Black Sheep Squadron’s success was in its own way a victory for the principles of individual initiative and creative thinking that democratic societies foster and authoritarian regimes suppress. Today, as new challenges emerge and new conflicts threaten global stability, the story of VMF 214 provides both inspiration and instruction.

It reminds us that even in the face of overwhelming odds, determined individuals can find ways to prevail. And it demonstrates that sometimes the most unlikely heroes are exactly what the world needs to overcome its greatest challenges. The black sheep may have been misfits, but they were misfits who changed the world. And in doing so, they proved that sometimes being different isn’t a weakness. It’s exactly the strength the situation demands.

News

Gorilla Adopts Three Lion Cubs — What Happened Months Later Will Astonish You!

What if the greatest act of love meant risking everything, even breaking the most ancient laws of nature? Deep in…

She Saved This Lion 12 Years Ago. Now It Returned to Her Door BEGGING for Help

the white wooden door creaked as Sarah Miller pulled it open squinting against the golden afternoon light that flooded her…

She Found the Alpha King Trapped as a Helpless Wolf Pup — His Pack Called Her True Luna

Lyra checked her gathering basket one final time, making sure the leather straps were secure, and the lined interior would…

She Saved This Lion 12 Years Ago. Now It Returned to Her Door BEGGING for Help

The blizzard didn’t just bite, it consumed. In the frozen heart of the whispering spine forest, a young woman named…

She Used Her Last Strength to Save a Wolf Cub— The Alpha King Found Her Unconscious

The blizzard didn’t just bite, it consumed. In the frozen heart of the whispering spine forest, a young woman named…

They Released Predator Cubs to Break Her Nerve—The Cubs Curled Up Beside sit Her Instead

Kate Morrison felt her heart sink when the emergency pod stopped working. The rescue signal that should have helped her…

End of content

No more pages to load