The names Hatfield and McCoy do not merely belong to history; they are carved into the very foundation of American folklore. They evoke a primal tale of vengeance, pride, and lawlessness set against the rugged backdrop of the Appalachian Mountains. For over two decades, this escalating cycle of retribution consumed two legendary families residing on opposite banks of the Tug River, a natural border separating the prideful state of Kentucky and the Union-breakaway of West Virginia. Yet, beneath the sensationalized headlines of “yellow journalism” and the romanticized legend, lies a profound tragedy: a story of how a minor land and hog dispute, fueled by the lingering bitterness of the Civil War, could utterly destroy two proud families and bring two states to the brink of armed conflict.

The Seeds of Strife: A Nation Divided and a Feud Ignited

To truly understand the Hatfield-McCoy feud, one must look past the 1878 Hog Trial, often cited as the starting point, and instead examine the broken landscape left behind by the American Civil War. The Tug River Valley was a brutal battleground where neighbors were forced to choose sides, often turning against one another in localized, guerrilla-style home guard skirmishes. When the formal war ended, the underlying grudges festered.

On the West Virginia side resided William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield, a formidable, uneducated, yet shrewd natural leader. An expert marksman and successful logging operator, he commanded his own small army of 20-some roughneck men. He was a man not to be trifled with. Across the river in Kentucky lived Randolph “Randall” McCoy, a simple farmer and woodsman. Unlike the prosperous Devil Anse, Randall was not a successful businessman and often found himself at a disadvantage. While both men held Confederate sympathies, the complex post-war environment—where West Virginia seceded to join the Union—created a chaotic legal vacuum: a period of “total lawlessness” with no civil authority, no courts, and no sheriffs.

The first death attributed to the feud came in 1865: Asa Harmon McCoy, Randall’s younger brother, and the sole member of the family who sided with the Union Army. Upon returning home, Harmon found himself the target of Confederate sympathizers, including Devil Anse’s Wildcats. Asa Harmon was ambushed and killed. While historians debate if this was the true catalyst, the murder of a brother is not an act easily forgotten or forgiven. The seeds of revenge had been planted in Randall McCoy’s heart, a wound that would grow deeper with every passing year.

The Hog Trial and the Ultimate Insult

The year 1878 brought a legal drama that would solidify the hatred between the two clans: the infamous Hog Trial. In the subsistence-farming culture of the Appalachian Mountains, a hog was a vital source of protein and survival. When Floyd Hatfield (a cousin of Devil Anse) claimed a hog that Randall McCoy swore was his, the dispute went to the only justice of the peace in the area: Preacher Anse Hatfield.

Despite the families’ reputation for vigilantism, the Hatfields were “exceptionally litigious,” often seeking legal recourse. The jury was stacked with six Hatfields and six McCoys, suggesting a guaranteed hung jury. However, the testimony of a key witness, Bill Staton, swayed the verdict in favor of the Hatfields. The true shock came when Selkirk McCoy, Randall’s own flesh and blood, sided with the Hatfields, securing the victory for the rival clan.

Randall McCoy, who hadn’t forgotten the murder of his brother, viewed this loss as a devastating insult to his honor, compounded by the betrayal of his cousin. He refused to accept the verdict, his unhappiness turning to a public rage that drove people away. The battle was no longer just about a dead brother; it was about pride, public humiliation, and a deep sense of injustice.

Roseanna and Johnse: The Star-Crossed Tinderbox

As the two patriarchs simmered in their hatred, a forbidden romance bloomed that would pour emotional gasoline onto the growing fire. In 1880, at an election day social gathering, Johnse Hatfield, Devil Anse’s handsome, blonde-haired, blue-eyed, 18-year-old son, locked eyes with Roseanna McCoy, Randall’s 21-year-old daughter.

Their attraction was immediate and powerful, leading them to slip off into the woods for a romantic liaison. Fearing her father’s wrath, Roseanna did not return home, instead crossing the river to the Hatfield cabin, where Johnse promised to marry her. Though Johnse’s father, Devil Anse, initially opposed the marriage, Roseanna stayed, eventually becoming pregnant.

However, the romance proved ill-fated. Johnse, a known ladies’ man, abandoned the pregnant Roseanna for other women. The final, heartbreaking break came after Randall McCoy, unforgiving of her defiance, refused to allow his daughter back under his roof. This forced Roseanna to live with an aunt, her daughter, little Sally, tragically dying at only eight months old. The family schism was complete.

The ultimate act of emotional betrayal, however, was Roseanna’s warning to Johnse that her brothers were planning to capture him on outstanding moonshine charges. She rode alone through the rough, dark mountains, a courageous act of love that her family saw as the “ultimate betrayal.” She chose her lover over her clan, enabling Devil Anse to rescue his son and humiliate the McCoy boys in a tense, but bloodless, confrontation. This event, Jim McCoy’s refusal to kneel notwithstanding, raised the “volume of vitriol” between the men to an incendiary level.

A Death Watch, a Promise, and the Paw Paw Massacre

The feud found its irreversible turning point in August 1882 during another election day gathering. A brawl erupted over a $1.75 debt owed for a fiddle between Tolbert McCoy (Randall’s son) and Bad Elias Hatfield (Preacher Anse’s brother). Ellison Hatfield, Devil Anse’s brother, intervened, and the fight quickly devolved into savage mountain combat involving knives, grappling, and kicking. Ellison was brutally attacked by Tolbert and his brothers, Farmer and Bill (though Bud McCoy Jr. took the 14-year-old’s place in the subsequent arrest). Ellison Hatfield was stabbed more than 27 times and shot, left mortally wounded.

The three McCoy brothers were arrested and held, destined for jail in Pikeville, Kentucky. However, before the law could deliver justice, Devil Anse Hatfield intercepted the lawmen and, backed by a superior posse, seized the prisoners. A death watch began over the dying Ellison. Meanwhile, the McCoy boys’ mother, Sarah “Sally” McCoy, bravely ventured into Hatfield territory to beg Devil Anse for mercy, pleading that her sons be tried in Kentucky.

Devil Anse’s cold response was a promise: “If Ellison lives, I’ll let that happen… But if Ellison dies, we’ll try them right here.”

On the third day, Ellison Hatfield died. Keeping his grim word, Devil Anse led the three young, tied-up McCoy brothers across the Tug River to a spot by Paw Paw bushes. In an act of ruthless mountain justice, Tolbert (23) and Farmer (18) were executed by firing squad. The posse hesitated before killing 15-year-old Bud, but Devil Anse, driven by vengeance, uttered the infamous phrase, “Dead men tell no tales,” and personally put a Winchester to the boy’s head, blowing his skull off. The Paw Paw Massacre, though rooted in the lawless vacuum of the region, was a calculated act of murder, setting the stage for a full-scale legal war.

The Lawyer’s Grudge and the New Year’s Day Horror

Randall McCoy spent the next five years seeking justice for his murdered sons, only to be frustrated by the lack of extradition between the states. He finally turned to Perry Cline, a wealthy Pikeville attorney and a distant relative by marriage. Cline, however, was also driven by a 16-year-old personal vendetta: Devil Anse had, through legal means in a West Virginia court, successfully seized 5,000 acres of Cline’s timberland. Cline saw the feud as his path to revenge, using Randall McCoy as a “pawn on Perry’s chessboard.”

Using his political influence, Cline got Kentucky Governor Simon Bolivar Buckner to post bounties on the Hatfields’ heads, including $500 for Devil Anse. Cline then hired the infamous “Bad” Frank Phillips, a ruthless and violent lawman who took no prisoners.

The Hatfields, fearing arrest, retaliated in a heinous act of intimidation. At sunrise on New Year’s Day 1888, a Hatfield posse led by the aggressive Jim Vance and Johnse Hatfield, attacked Randall McCoy’s cabin. The Hatfields, intending to drive the McCoys out of the area and stop their testimony, set fire to the home and shot into the windows. When 16-year-old daughter Alafair McCoy tried to flee, she was shot. Randall’s son, Calvin, was killed in the yard. Sarah McCoy rushed out and was clubbed into unconsciousness by Johnse Hatfield. This premeditated attack, the killing of a daughter and son and the maiming of a mother, was the “egregious, the heinous act of the feud that made the Hatfields clearly the bad guys.”

From Appalachian Hollow to the Supreme Court

Following the New Year’s Day Massacre, Frank Phillips intensified his raids. He cornered and killed Jim Vance, shooting him in the head as he lay dying. This illegal murder on West Virginia soil—a blatant, ruthless act—escalated the crisis from a local feud to a national constitutional issue, pitting the governors of Kentucky and West Virginia against each other.

The feud became a media circus, feeding the public’s fascination with the “hill people” and ushering in an era of “yellow journalism” that sensationalized the lurid details. The legal battle culminated in a U.S. Supreme Court case in Louisville, arguing whether prisoners illegally captured in West Virginia could be held and tried in Kentucky. The court ruled that, regardless of how they were captured, Kentucky had the legal right to try the prisoners wanted for murder in their state.

In August 1889, seven years after the executions, the trials began in Pikeville, Kentucky. Eight of the captured Hatfields and supporters were sentenced to life in prison. But the jury saved its toughest verdict for Ellison “Cotton Top” Mounts, the illegitimate son of Devil Anse’s murdered brother Ellison.

Mounts, described as simple and of low intelligence, had given the only full confession, detailing the murders of both the McCoy boys and Alafair McCoy. He became the perfect “scapegoat.” People, fueled by years of violence, demanded blood. Mounts was sentenced to death by hanging. On a cold winter day, February 18, 1890, in front of hundreds of onlookers, Ellison Mounts was hanged, the last official death of the quarter-century-long feud, shouting, “The Hatfields made me do it.”

The Final Tally and a Tale of Two Patriarchs

The execution of Ellison Mounts brought a sort of morbid closure, effectively ending the violent phase of the feud. The feud claimed the lives of 11 family members and supporters, but the true toll was the psychological devastation it wrought.

The ultimate tragedy, however, is best illustrated by the contrasting fates of the two patriarchs.

Devil Anse Hatfield, the shrewd outlaw and successful businessman, lived to the grand age of 81. He died peacefully in 1921, having built a grand house and prospered from his logging operation. His funeral was attended by over 5,000 people, and his family commissioned a life-sized statue of Italian marble for his grave, venerating him as a hero.

Randall McCoy, the haunted patriarch who lost a brother, four sons, and a daughter, and saw his wife permanently damaged, spent his final years in Pikeville, “haunted by the deaths of his children.” He often wandered the streets, “raving about his losses and his hate for the Hatfields.” He died in 1914, virtually destitute, and was buried in a modest, private ceremony.

The Hatfield-McCoy feud stands as a powerful and dark chapter in American history, not just as a bloody frontier tale, but as a chilling lesson in what happens when the bonds of civil society break down, allowing unchecked pride, lawlessness, and a cycle of revenge to consume a community. The conflict was a continuation of a nation divided, where the lack of infrastructure and governance allowed deep-seated bitterness to escalate beyond control, ultimately requiring the intervention of the highest court in the land to secure a semblance of justice. It remains, as historians suggest, a complex American archetype—a profound illustration of tough, moral people driven to violence by the cauldron of their isolated circumstances.

News

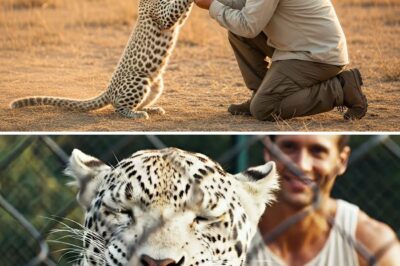

A White Leopard Cub Begged a Man for Help – And Then an Incredible Journey Began

A desperate cry sliced through the silence of the East African dawn. It wasn’t the roar of a predator or…

Black Panther Trapped in Net Hanging from Tree, Begging for Help – Then the Unthinkable Happens

A gut-wrenching cry splits the morning calm. High in the canopy, suspended between the earth and the sky. A black…

A Dog Nursed Abandoned Lion Cubs, But Two Years Later Something Shocking Happened!

Welcome to the Serengeti National Reserve, the heart of Africa, where life and instinct reign supreme on the endless plains….

A Bone-Thin Lion Lunged at a Ranger Like a Hungry Predator — The Twist No One Saw Coming

A blur of bone and desperate fury launched itself across the sunbaked earth. Claws long and deadly were unshathed. Jaws…

The human fed the chained wolf daily… until the chains broke and the Alpha King rose before her.

Fortress that served as humanity’s last bastion of defense against invasion. Greystone Fortress was an imposing structure of high walls…

She Hid in an Abandoned Cabin… Until the Alpha King Found Her

I didn’t mean to run. Not at first. People like me weren’t supposed to make choices. We were supposed to…

End of content

No more pages to load