March 7th, 1944, 12,000 ft above Brandenburg, Oberloitant Wilhelm Huffman of Yagashwatter, 11 spotted the incoming bomber stream. 400 B7s stretched across the horizon like a plague of locusts. He’d seen this before. The Americans would drop their bombs and turn for home. And somewhere around Hanover, their little friends would peel away, low on fuel, leaving the bombers naked for the slaughter.

Hoffman checked his fuel gauge. Full tanks. 3 hours of combat time. The Mustangs, those new American fighters with their ridiculous bubble canopies and garish nose art, would be lucky to have 45 minutes over target. The mathematics of aerial warfare were simple. A P-51 consumed 65 gall per hour at cruise settings.

Their drop tanks gave them an extra 150 gallons each, but combat maneuvering tripled fuel consumption. By the time they reached Berlin, they’d be flying on fumes. He remembered the briefing from last week. Major Klaus Bretch Schneider had actually laughed when intelligence reported the Americans were claiming five-hour missions with their new fighters.

“5 hours?” Brett Schneider had said, slapping the table. “My grandmother could fly 5 hours in a glider. These Mustangs are nothing but polished Spitfires with bigger fuel tanks. They’ll turn back at Dumber Lake like they always do.” The first indication something was different came from Feld Veil Ernst Miller flying 2,000 ft below.

Klein Fender approaching from the west. They’re they’re not breaking off. Hoffman frowned. The escort fighters were still with the bombers well past their usual turnback point. Through the haze, he could make out the distinctive shapes of P-51s, their laminar flow wings unmistakable even at distance. But that was impossible. They should be heading home by now, engines coughing on vapor.

What Hoffman didn’t know was that 3 months earlier in a converted furniture factory in Englewood, California, North American Aviation had performed a miracle of engineering that would rewrite the mathematics of air combat. They had taken a good fighter and transformed it into something unprecedented. A fighter that could fly to Berlin and back. A fighter that could hunt.

The transformation began with a desperate telegram from the British in April 1940. They needed fighters, lots of them, fast. North American Aviation promised to deliver a prototype in 120 days. Most companies took 2 years. Edgar Schmood, the company’s chief designer, didn’t sleep for the first 72 hours.

He pulled engineers off every other project. The draft tables ran 24 hours a day. The initial design, designated NA73X, flew for the first time on October 26th, 1940. It was good, but not exceptional. The Allison engine provided adequate power at low altitude, but wheezed above 15,000 ft.

The British took delivery and named it the Mustang Mark Guster. They used it for reconnaissance and ground attack. Nobody thought it would amount to much more. Then in April 1942, a Rolls-Royce test pilot named Ronald Harker flew a Mustang Y and had an epiphany. The airframe was superb, better than anything the British had produced.

The Laminar flow wing, an innovation that kept air flowing smoothly over the surface far longer than conventional designs, gave it remarkable speed and efficiency. But that Allison engine was killing its potential. Harker wrote a three-page memo that would change the war. Marry this airframe to our Merlin engine, he urged, and you’ll have the best fighter in the world.

The first Merlin powered Mustang flew on November the 30th, 1942. The transformation was staggering. Maximum speed jumped from 390 to 440 mph. Service ceilings soared from 30,000 to 42,000 ft. But the real revolution lay hidden in the fuel consumption figures. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Hitchcock, the American military atache in London, cabled Washington with barely contained excitement.

New Mustang with Merlin engine shows fuel consumption of only 43 gall per hour at 25,000 ft. 300 mph crews. This changes everything. The mathematics that Major Brett Schneider had laughed at were actually conservative. A P-51D carried 269 gall internally plus two 110gal drop tanks. At optimum cruise settings, it burned just 43 gall per hour.

That gave it a theoretical range of over 2,000 m. Berlin was 750 mi from British bases. The Mustang could fly there, fight for 30 minutes, and fly home with fuel to spare. Back over Brandenburgg, Huffman was about to discover what this meant. He led his schwarm in a diving attack on the bomber formation. The standard tactic that had worked for three years.

Strike hard, strike fast, then climb away before the escorts could react. But as he lined up on a straggling B17, his wingman’s voice crackled through the radio. Mustangs, they’re following us down. This was new. American escorts typically stayed high protecting the bomber stream. They couldn’t afford to waste fuel chasing individual German fighters.

But these Mustangs were different. They had fuel to burn. Captain Donald Gentile of the fourth fighter group had been waiting for this moment. His P-51B, nicknamed Shangri Law, carried enough fuel for 5 and a half hours of flight time. He’d taken off from Debbon at 0830 hours, rendevued with the bombers over the Dutch coast, and still had 4 hours of fuel remaining.

When he saw the 109s diving on the bombers, he didn’t hesitate. Horseback leader, this is horseback one. Bandits 2:00 low, going down. The mathematics of energy management in aerial combat were unforgiving. Every foot of altitude represented potential energy. Every mile per hour of speed was kinetic energy.

In the brutal calculus of dog fighting, energy was life. The German pilots had perfected the art of energy conservation, making slashing attacks and using their altitude advantage to escape. But they’d never faced escorts that could afford to spend energy proflegately. Gentile pushed his throttle to war emergency power.

The Merlin engine screamed to 3,000 RPM, gulping fuel at 150 gall hour. In a Spitfire or P47, such extravagance would leave him gliding home. In the Mustang, he could maintain this setting for 20 minutes and still have reserves. Hoffman saw the Mustangs coming, but wasn’t concerned. He’d been bounced by escorts before. A quick burst at the bomber, a half roll, a dive to gain separation, and the Americans would break off.

They always broke off. They had to. But as he pulled the trigger, sending a stream of 20 mm cannon shells toward the B17’s number three engine, he realized the Mustang on his tail wasn’t breaking off. It was getting closer. The debriefing reports from German pilots in early 1944 make for fascinating reading. Hman Friedrich Beck of JG1 wrote, “The new American fighters exhibit puzzling behavior.

They pursue to very low altitudes and vast distances from bomber formations. Our traditional tactics of drawing them away from the bombers no longer work. They seem to have unlimited fuel. He wasn’t wrong. Colonel Hubert Zena, commander of the 56th Fighter Group, had revolutionized escort tactics based on the Mustangs capabilities.

Forget about staying close to the bombers, he told his pilots. Your job is to clear the sky of German fighters. Hunt them, chase them, run them down. You’ve got the fuel. Use it. This shift from defensive to offensive escort tactics shattered German interceptor doctrine. For three years, they’d relied on the fuel limitations of Allied escorts to create windows of opportunity.

They would loiter just outside escort range, wait for the little friends to turn back, then pounce on the unprotected bombers. The Mustang closed that window and nailed it shut. Major Gunther Spect commanding JG11 recorded his frustration in a March 1944 report to fighter command. The new American long range fighters appear over our airfields as we are landing.

They follow us down to treetop level. They circle our bases waiting for us to take off. We are being hunted in our own airspace. The numbers tell the story with brutal clarity. In January 1944, before the Mustang achieved numerical superiority, the 8th Air Force lost 377 heavy bombers. By May, with Mustangs flying 60% of escort missions, losses dropped to 148.

German fighter losses showed the inverse relationship. January saw the Luftvafa lose 307 fighters. By May, that number had climbed to 432. But the real revolution wasn’t just in the numbers. It was in the psychology of air combat. Lieutenant Hines Koke of JG11 captured it in his diary. The hunters have become the hunted.

We take off knowing the Americans will be waiting. We can no longer choose when to fight. They are always there, like sharks circling a sinking ship. The Mustang’s range allowed for tactics that would have been suicidal in any other fighter. Freelancing became the watchword. After escorting bombers to target, Mustang pilots would drop to the deck and strafe targets of opportunity.

Airfields, rail yards, vehicle convoys, anything that moved. They’d arrive back at base with gun camera footage of locomotives exploding and Messor Schmidtz burning on the ground. Technical Sergeant Charles Bailey, a crew chief with the 357th Fighter Group, remembered the change in pilot attitudes.

Early in 44, they’d come back talking about how many bombers they’d saved. By summer, they were competing to see who could shoot up the most trains. One pilot, Captain Fletcher Adams, came back with tree branches in his air scoop. He’d been flying that low. The Germans tried to adapt. They experimented with larger drop tanks for their own fighters, but the Mustang’s fundamental efficiency advantage couldn’t be matched.

A Messormidt BF 109G burned 70 gallons per hour at cruise settings. A Foca Wolf 190 consumed even more. Even with drop tanks, they couldn’t match the Americans range. In desperation, the Luvafa developed new tactics. Company front attacks masked 40 to 60 fighters into a single devastating pass through the bomber formation.

But these required assembly time, and the roving mustangs would break them up before they could form. The mathematics of attrition were inexurable. Every German pilot lost represented years of training that couldn’t be replaced. Every American pilot lost was replaced by two more. Products of a training system producing 3,000 new pilots per month.

General Adolf Galland, commander of German fighter forces, saw the writing on the wall. In a post-war interrogation, he stated, “The Mustang was the decisive weapon, not because it was superior to our fighters in combat, though it was very good, but because it could be everywhere. We could no longer find safety anywhere.

Even our training bases in Czechoslovakia were under attack.” The production figures added another dimension to Germany’s nightmare. North American Aviation’s Englewood plant was producing 20 Mustangs per day by mid 1944. The Dallas plant added another 15. Monthly production peaked at 630 Mustangs in December 1944. During the entire war, Germany produced approximately 33,000 single engine fighters of all types.

North American built 15,586 Mustangs with production accelerating even as German factories were being destroyed. Colonel Johanna Steinhoff, commanding JG77, wrote a desperate memorandum in September 1944. The enemy’s numerical superiority is crushing, but worse is their operational freedom. Our pilots must fight over their own airfields.

They must conserve fuel while the Americans burn it freely. They must calculate every maneuver while the enemy attacks with abandon. We are fighting the arithmetic of the possible against the arithmetic of abundance. The kill ratios reflected this new reality. In 1943, German fighters claimed three Allied aircraft for every loss.

By late 1944, Mustangs were claiming six German aircraft for every loss. The top American aces were all flying Mustangs. Major George Prey scored 26 victories. Colonel John Meyer claimed 24. Captain Don Gentile got 23. These weren’t just defensive victories protecting bombers. These were hunting victories. German fighters caught taking off, landing, or trying to return to base.

The Mustang’s impact extended beyond pure fighter combat. Operation Jackpot, launched in May 1944, specifically targeted German training bases. Mustangs would fly 700mile missions to catch student pilots in the air. On May 29th, Mustangs from the 78th Fighter Group caught an entire training flight over Leipik.

12 Messesmmit 109s flown by student pilots were shot down in 4 minutes. The instructors flying alongside their students were powerless to intervene. Oberfeld Vable Ziggfrieded Bethka, a flight instructor with Yagflea 103, survived one such encounter. We were practicing formation flying, just basic maneuvers.

Suddenly, there were mustangs everywhere. My students had perhaps 20 hours in fighters. The Americans had hundreds. It was not combat. It was execution. By December 1944, Germany had essentially lost daylight air superiority over its own territory. The Arden offensive, Hitler’s last gamble in the West, launched on December 16th with explicit orders to attack only in bad weather.

The reason was simple. Clear skies meant mustangs and mustangs meant annihilation. General Dar Yagfleager Gordon Golop summed up the German pilots dilemma in a staff meeting that month. Our pilots take off knowing they are already outnumbered 5 to one. They know the Americans have better fuel supplies, better aircraft, and better everything.

But worst of all, they know the Americans can follow them home. There is no respit, no sanctuary, no moment of safety from takeoff to landing. The fuel situation had become so critical that German fighters were limited to one combat sorty per day and often not even that. Meanwhile, American pilots were flying double missions, take off at dawn, escort the morning raid to Munich, return for lunch and refueling, then escort the afternoon raid to Frankfurt.

The mathematics of war had turned into a mockery of Germans capabilities. Captain Robert Johnson of the 56th Fighter Group described a typical late war mission. We’d escort the bombers to target, then half of us would go hunting. I’d drop down to 5,000 ft and fly east until I found something. Rail lines, airfields, convoys.

The crowds had to move in daylight sometimes, and when they did, we were there. I once chased a single truck for 30 miles. Why? Because I could. Because I had the fuel. The Mustang even changed the nature of air combat training. American pilots arriving in England received extensive instruction in fuel management, not to conserve it, but to maximize their hunting time.

They learned to fly at specific RPM settings and manifold pressures that would give them an extra 30 minutes over enemy territory. German pilots, conversely, were taught to minimize combat time and conserve every drop of fuel for the return flight. The psychological impact on German pilots was devastating. Litant Oscar Bush of JG3 wrote to his wife in February 1945, “The Americans own the sky.

We take off in darkness and land in darkness. Even then, they sometimes catch us with their navigation lights off, hunting by sound. Last week, Weber was shot down in the landing pattern, geared down, flaps extended. The American followed him through the entire approach and killed him 500 m from the runway. By March 1945, the Luftvafa was operating under a doctrine of ramager, or ramming attacks.

Volunteer pilots would attempt to ram American bombers, bailing out at the last second if possible. It was a tactic of utter desperation, born from the mathematical impossibility of conventional interception. Even these suicide attacks were often frustrated by Mustangs, which would shoot down the ramming fighters before they could reach the bombers.

The final statistics are staggering. Mustangs flew 213,873 sorties over Europe. They dropped 500,000 gallons of napal, fired over 4 million rounds of ammunition, and claimed 4,950 aerial victories. They lost 2,520 aircraft to all causes. The mathematics work out to one Mustang lost for every 85 sorties and two German aircraft destroyed for every Mustang lost to enemy action.

But perhaps the most telling statistic is this. By April 1945, the average experience level of a German fighter pilot was less than 50 hours in type. The average American Mustang pilot had over 400 hours. The mathematics of attrition had reached their logical conclusion. Germany had run out of experienced pilots faster than it had run out of aircraft.

General Derfleager Ysef Schmidt in a post-war analysis wrote the epitap for the Luftvafa fighter force. The Mustang didn’t defeat us through superior performance, though it was a superb aircraft. It defeated us through superior presence. It was always there. In numbers, we couldn’t match. With endurance, we couldn’t equal.

Flown by pilots, we couldn’t train fast enough to replace our losses. The mathematics of modern war had rendered our skills irrelevant. The lessons learned over Germany’s flaming cities resonate today. Modern air forces still grapple with the tyranny of distance and the arithmetic of fuel consumption.

The F-22 Raptor, for all its technological sophistication, has a combat radius of only 600 m. The Mustang, designed with slide rules and wind tunnels, could fight at 750 mi from base. Sometimes the mathematics of war come down to simple endurance. Wilhelm Hoffman, the German pilot we met over Brandenburgg, survived the war.

In a 1985 interview, he reflected on that March day when everything changed. We had trained for short, sharp engagements, climb, attack, dive away, land. The Mustang pilots fought like they had all day because they did. And when I finally shot down my first Mustang in January 45, I was so low on fuel I had to glide the last 10 kilometers to my airfield.

As I climbed out of my aircraft, another Mustang strafed the field. He had followed me home, watching me land, waiting for the perfect moment. That was when I truly understood. They weren’t just escorts anymore. They were hunters and we were the prey. The mathematics of air warfare had been rewritten in the skies over Europe.

Distance divided by fuel consumption multiplied by tactical aggression equaled air supremacy. It was an equation written in aluminum and gasoline, solved by young men at 25,000 ft and paid for in blood and burning aircraft. The Mustang had indeed lived up to Ronald Harker’s prediction. It had become the best fighter in the world. Not through superior dog fighting capability, though it had that, but through something more fundamental.

It had redefined what a fighter could do and where it could do it. The laughter in German briefing rooms had long since died away, replaced by the grim arithmetic of survival against impossible odds. The hunters of the Luftwafa had discovered a harsh truth. When the mathematics of war shift against you, when your enemy can go wherever you can go and stay longer, when he gets there, courage and skill become academic exercises.

The Mustang hadn’t just extended fighter range. It had extended American power projection to every corner of Nazi Germany’s crumbling empire. And in doing so, it had painted the equation for modern air superiority that still defines aerial warfare today. Control of the air goes not to the best dog fighter, but to the force that can put the most fighters in the most places for the most time.

It’s a simple equation with a complex solution. one that North American aviation solved with a Packardbuilt British engine in an American airframe, creating a hybrid that rewrote the mathematics of the possible. In the end, the Germans learned what happened when American industrial might was married to British engineering excellence and pointed east.

They learned that the arithmetic of abundance would always defeat the arithmetic of scarcity. They learned that when your enemy’s fighters can fly to your capital city, orbit for half an hour looking for targets, and still fly home, you have not just lost air superiority. You have lost the war. The Mustang proved that in modern warfare, logistics is not just important, it is everything.

The best fighter in the world is not the one that can outturn or outclimb its opponents. It is the one that can show up over the battlefield again and again in numbers that matter with fuel to fight. The German pilots of 1944 learned this lesson in the hardest classroom imaginable. At 25,000 ft with mustangs on their tail and nowhere left to run, they discovered that the mathematics of war are as inflexible as the laws of physics and as unforgiving as gravity itself.

News

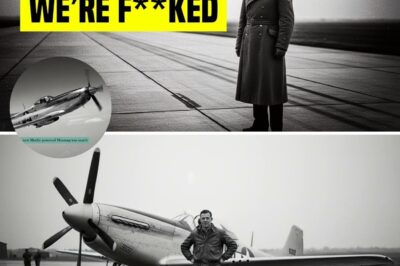

German Aces Mocked the P-51 Mustang — Until 200 of Them Appeared Over Berlin

The German aces laughed at the P-51 Mustang. They called it a mediocre performer. Nothing to worry about. Then on…

Idaho 1973 Cold Case Solved — Arrest Shocks Community

Dinner was still warm on the table when James and Rebecca Turner disappeared from their farmhouse on the edge of…

20 Students Vanished After School in 1994 — 30 Years Later, Their Bus Was Found Buried in the Woods

In 1994, a school bus vanished in rural Georgia. 20 children climbed aboard. None ever came home. For three decades,…

Five Cousins Vanished From a Texas Lodge in 1997 — FBI Discovery in 2024 Shocked Everyone

In the fall of 1997, five cousins gathered for what was supposed to be a quiet weekend reunion at their…

Four Siblings Vanished in 1986 — What Was Found in 2024 Changed the Whole Investigation…

In 1986, three siblings were rescued from a hoarder house in rural Indiana. Their parents were arrested. The news made…

Girl Tries to Touch an Angry Gorilla, What He Does Next Is Shocking!!

They called her the Phantom Gorilla, a 300-PB body with a soul that had vanished. No one thought she’d ever…

End of content

No more pages to load