In 1838, Dublin witnessed the birth of two children who should never have existed. Twins so unnatural that both priests and doctors begged for their names to be forgotten. The Callahan twins were said to mirror each other perfectly, as if sharing one soul in two bodies.

They spoke words they had no way of knowing, endured things no child should survive, and their very blood seemed to defy nature. Their case terrified the city, fractured the church, and left science desperate to hide what it could not explain. For nearly two centuries, their story has been erased, censored, and buried.

Yet fragments still whisper of what truly happened. Dublin in the 1830s was a city of contradictions. The cobbled lanes echoed with the songs of street vendors and the rattle of carriage wheels. Yet beneath the noise lay an unease, a city torn between the old world of superstition and the new promise of science.

The Callahan family lived in the narrow back streets near the Liberties, where smoke from distilleries blackened the sky, and rumors traveled faster than the cold wind off the river Liffey. It was here in 1838 that a set of twins was born, who would soon become the city’s most whispered secret. Their names were never properly recorded.

Some say they were baptized. Others insist the priests refused to allow it. What is certain is that from the very moment they entered the world, midwives and neighbors alike spoke of omens, candles blowing out in the birthing room, the sound of knocking on the walls when no one stood outside, and a stillness in the air that felt heavier than silence.

The twins themselves appeared healthy, yet strangely alike, in a way that unsettled even seasoned physicians. They did not cry separately, but in a single harmonized whale, as though one voice split into two bodies. Their mother, exhausted and pale, was said to whisper that she felt them moving even when one was asleep in her arms. Their father, a laborer named Michael Callahan, dismissed it as nerves.

Yet the neighbors soon gave the infants names of their own, the mirror children. At first Dublin’s curiosity outweighed its fear. Families came to see the little girls, marveling at how they moved together, turned their heads in perfect sink, and seemed to know when one was touched, even if the other was across the room. Doctors from the city’s fledgling medical college took interest, recording their first observations in worn leather journals that decades later would mysteriously vanish from archives. But admiration quickly soured.

When illness swept through the neighborhood, leaving other infants dead, whispers began. Why were the Callahan twins untouched? Why did sickness stop at their door as though unwilling to enter? The church, too, took notice. Priests muttered of unnatural bonds, of creatures born not of God’s design, but of something darker.

Parishioners were warned not to spend too much time in the Callahan home, and in the shadows of Dublin’s taverns and markets, the story began to spread that two children had been born who were not like us, and that their very existence was an affront to both heaven and reason. And so the stage was set. The Callahan twins had entered the world, but what awaited them was not the warmth of a city’s embrace.

It was the cold scrutiny of science and the unforgiving suspicion of faith. The Callahan family was not wealthy, nor were they influential. Michael Callahan earned his living as a laborer, moving between work at the docks and the city’s growing network of factories. His wife, Bridg, came from a long line of midwives and herbalists, women who were both respected and mistrusted in equal measure.

Their home was modest, two small rooms crowded with siblings, an iron stove that smoked more than it burned, and floors damp from the constant chill of the Irish weather. Life was hard, but not unusual, for Dublin in the 1830s. Poverty touched nearly every family.

Disease stalked the streets, and superstition filled the spaces science had not yet claimed. In that world, children were both a blessing and a burden. When the twins arrived, neighbors first offered food and help, bringing bread or mending cloth to ease the weight of two new mouths, but their kindness soon shifted into nervous distance. The girls grew quickly and always in uncanny symmetry. If one smiled, the other followed.

If one reached for her mother’s hand, the others fingers curled at the same instant, even if she was across the room. People whispered that their movements were not learned, but rehearsed, as though guided by something deeper than instinct.

Bridget defended her daughters, insisting that all twins shared such closeness. Yet even she, in her quieter moments, admitted to friends that she sometimes could not tell which child she held in her arms. As they passed their first year, rumors hardened into suspicion. local children avoided them, frightened by stories their parents repeated in hush tones, that the twins laughed at shadows no one else could see, or that they sang Lou, ladies in languages unknown to the family.

Michael dismissed it all as nonsense born of envy, but the parish priest began asking questions. Had the girls been properly baptized, were they brought regularly to mass? When Bridgette faltered in her answers, the priest warned her that unnatural children invited unnatural outcomes. Still, not everything was condemnation. A few men of science in Dublin saw the girls as a rare gift, living proof of mysteries yet to be unraveled.

Physicians spoke of new theories, of sympathetic bonds, and shared humors that might explain such mirror-like behavior. They asked permission to observe the twins more closely, promising no harm would come. Michael hesitated, but Bridg, perhaps sensing danger in refusal, agreed.

The girls were examined in dimly lit rooms filled with instruments of polished brass and glass, their tiny bodies measured, their pulses counted. The doctors recorded their findings with excitement, never realizing how far their fascination would drive events in the years to come. And so before the Callahan twins could even speak their first full words, they had already become more than children.

To the church they were a warning, to science a curiosity. To their neighbors, an omen. By the time the Callahan twins reached the age of three, their stranges could no longer be brushed aside as the charm of infancy. They spoke earlier than most children, yet not in the halting way toddlers usually did.

Their words came in full sentences, spoken in perfect unison, as if a single thought were split between two mouths. Bridg tried to hush them, to remind them that children their age should not know such words, but the girls often answered her questions before she asked them, finishing her thoughts aloud in a voice doubled by their echo. It unsettled even their own brothers and sisters, who began to keep away from them at play.

Neighbors told stories of how the girls seemed to know things they could not have witnessed. A man who lost his keys claimed the twins led him to the place where he had dropped them in a field the night before. A woman swore the girls described her husband’s illness before he even fell sick.

These stories spread quickly through the alleys of Dublin, fueled by a city already steeped in tales of banshees and ill omens. Every unexplained misfortune seemed to bend back toward the Callahan home. When milk spoiled too quickly or livestock sickened, whispers blamed the twins. Even more troubling was their health. Where other children suffered from coughs and fevers in the damp Dublin air, the Callahan girls remained untouched. They ran barefoot in the rain and returned without so much as a chill.

Their cheeks were always bright, their skin unmarked by the common rashes and soores that plagued children of their class. Some called it a blessing. Others said it was proof they were not like other children at all. Bridg clung to her faith that her daughters were merely unusual, but even she began to notice things that frightened her.

At night, when she believed them asleep, she sometimes heard the girls whispering to each other in a language, e she did not recognize. On other nights she swore she heard only one voice, though both mouths moved in the faint moonlight. When she tried to wake them, they did not stir until the first cockcrow, as though they had been listening to something she could not hear. The priests by now had turned cold. Parish visits became interrogations.

Parishioners were told to pray for the Callahanss, though many understood this as a warning to keep away. The word unnatural began to cling to the family like a stain. And as the twins grew, it became increasingly clear that whatever bound them together was more than blood.

It was something no one could explain, and perhaps no one wanted to. By the time the girls were nearing their fifth year, the weight of suspicion pressed more heavily upon the Callahan household, Dublin was a city where the church’s word still carried absolute authority, and priests spoke from the pulpit with the gravity of law. Week after week, subtle warnings began to creep into sermons.

Tales of children marked by the devil. Stories of unnatural bonds and the dangers of those born under ominous signs. Though no names were spoken, every parishioner knew who was being described. Mothers clutched their children closer as Bridg led her twins down the church aisle, and whispers followed them through the pews like shadows. The priests themselves visited the Callahan home on more than one occasion.

At first their tone was pastoral, asking after the girl’s health, urging Bridgette to keep them within the discipline of the church. But as time passed, those visits grew colder. Questions became accusations? Were the children baptized properly? Why did they speak in tongues unknown? Why did misfortune seem to linger wherever they played? Bridg, already weary from constant gossip, could only insist that her daughters were innocent, though even her own voice sometimes faltered. Then came the incident that changed whispers into open fear. One evening, a

neighbor’s livestock, an entire pen of goats, was found dead, their bodies lying in eerie stillness without wound or mark. That same night, the twins had been seen playing near the pen, giggling in their mirrored way as if sharing a private joke. Though no one had proof, the conclusion was immediate. The girls had brought misfortune upon the animals.

By morning the story had spread beyond their street, and men gathered outside the Callahan home, muttering of curses and unholy power. The priests seized upon the moment. In the next Sunday sermon, Father O’Reilly spoke with fire in his voice about children born of darkness, about the dangers of harboring sin within the community. Though he again withheld their name, the warning was unmistakable.

Families who once tolerated the twins now avoided them completely. Invitations to share meals ceased. Children crossed themselves when the girls passed in the street. Even Bridgette began to sense the distance growing between her family and the rest of Dublin.

Michael tried to protect his daughters, insisting that stories of curses were nonsense. But deep inside even he could not shake the unease of that night. The sight of two small girls staring silently from their window while the bodies of livestock were drag ed from the neighbors pen. For Dublin the Callahan twins were no longer a curiosity. They had become a threat, a shadow lingering in plain sight.

And though no proof could be offered, the people believed what they wanted to believe, that something unnatural had entered their midst, and that it would not end quietly. The aftermath of the livestock deaths left the Callahan family marked in ways no denial could erase. Though Michael swore his daughters had nothing to do with it, and Bridg begged neighbors not to spread tales, the story had taken root.

In Dublin, rumor often held more weight than fact, and the image of the twins giggling near the goat pen was enough to brand them guilty in the eyes of most. People began crossing the street to avoid them. Shopkeepers grew reluctant to serve Bridg, some even refusing to take her money for fear it carried misfortune. The girls themselves seemed unaware of the storm around them, though their silence in public became more pronounced.

They clung to each other’s hands, eyes moving as one, their expressions unreadable to those who dared glance too long. Science, however, saw matters differently. A group of physicians from the Royal College of Surgeons declared the livestock deaths nothing more than happenstance. Disease or poison, they suggested, had claimed the animals, not some curse whispered by frightened villagers.

Their words were confident, but their actions betrayed unease. Several of the doctors kept personal notes on the twins, recording every unusual observation, their identical reflexes, their matched heartbeats, the way they seemed to anticipate each other’s movements with impossible precision. Officially, the incident was dismissed.

Unofficially, it deepened the fascination of men who believed the twins represented a mystery worth probing further. But the church’s position hardened. Priests muttered that coincidence was the very language of the devil, cloaking evil deeds beneath the guise of chance. Parishioners were instructed to be wary, to avoid unnecessary contact with the Callahanss. Even extended family began to distance themselves.

Bridg, once known for her skill with herbs and healing remedies, found fewer doors opening to her when neighbors fell ill. Her reputation, like her daughters, was collapsing under the weight of suspicion. At night, the family began to hear the change in their community. Stones tossed at the shutters, knocks on the door that vanished when answered, whispers carried in the dark. Witch’s children, devil’s twins.

Michael grew more protective, keeping his daughters indoors, though the twins themselves seemed strangely unbothered. When asked, they sometimes only smiled faintly, as if amused by the fear surrounding them. The city was dividing. To science, the twins were an oddity, a puzzle of flesh and blood. To faith, they were a danger, perhaps a doorway to darker things.

And for the people caught between, it was easier to believe the worst, because believing the worster offered an explanation, however terrible, for the unease that seemed to spread wherever the Callahan twins went. Dublin, in the late 1830s, was a city straining toward modernity.

The industrial revolution had swept across Britain, and though Ireland lagged behind, its capital was beginning to catch the fever of progress. Factories pressed their chimneys skyward. New machines hummed in workshops, and the hunger for knowledge became both fashionable and profitable. Science was no longer confined to dusty corners of monasteries or eccentric gentleman’s parlors.

It was being institutionalized, gathered into colleges and hospitals, polished into a discipline that promised to reshape society. The Royal College of Surgeons stood at the heart of this new era. Its marble halls and lecture theaters buzzing with students eager to dissect, to analyze, to measure.

In the same city where priests spoke of sin and salvation, young men in crisp coats whispered of anatomy, physiology, and the new frontier of experimentation. It was inevitable that the Callahan twins would draw their attention. For physicians who dreamed of making their names known in London or on the continent, the girls represented a living riddle. Identical twins were not rare, but the Callahanss were something else.

Mirror images who seemed less like siblings than two halves of a single body. Doctors speculated openly about whether their nervous systems were linked, whether unseen forces might explain their uncanny symmetry. Some spoke of magnetism, a concept then sweeping Europe, while others whispered of spiritual affinities cloaked in scientific terms.

Whatever the explanation, the twins promised discovery. And in Dublin’s competitive academic world, discovery meant prestige. Michael Callahan resisted. At first, he mistrusted men who wore polished shoes and asked questions he did not understand. But Bridg, ever aware of the growing hostility from neighbors and priests, feared that refusing would bring worse consequences.

To deny science might be seen as siding with superstition, and so reluctantly the family agreed to allow doctors limited access. The twins were escorted into halls where oil lamps flickered against walls lined with anatomical charts. They sat on cold wooden stools while hands measured their pulses, traced the shapes of their skulls, and tapped their knees with polished hammers.

Observers filled notebooks with scrolled notes, each more astonished than the last. What those physicians could not yet admit, even to themselves, was that their fascination had already begun to erode their skepticism. Each small anomaly recorded seemed less like coincidence and more like revelation. The Callahan twins were becoming more than subjects. They were becoming an obsession.

And obsessions, especially in Dublin’s fevered scientific world, had a way of pulling men beyond the boundaries of caution. The first formal examinations of the Callahan twins began quietly without notice in the papers or proclamations from the pulpit.

They were brought into the college under the guise of routine study, though every man present knew they were anything but ordinary children. The room smelled of ink and lamp oil, its high windows shuttered against curious eyes. A handful of physicians gathered around, notebooks open, quills poised as the girls sat hand in hand, their pale faces lit by the glow of lanterns. At first, the doctors tested what seemed simple.

They asked one child to lift her arm and the others followed in perfect rhythm as though pulled by unseen strings. They dropped a pin on the table and both heads turned at the same moment, their eyes tracking the movement with identical speed. They tapped the knee of one twin with a small hammer and both legs kicked in the same sharp motion. Notes were scribbled furiously.

Mirrored reflexes, indistinguishable responses. What astonished them most was not the similarity of the twins actions, but the precision, fractions of a second, no delay, no hesitation. It was as if two bodies were animated by a single command. When they pressed stethoscopes to the girls chests, they found their hearts beating in an impossible sink.

Not just the same rate, but the same cadence, as though the rhythm of life itself pulsed through them together. One doctor claimed he could hear no difference between the two heartbeats, as though he were listening to a single organ echoing in two rib cages. Another, more superstitious, muttered of a soul split in twain.

Further tests brought only more confusion. They blindfolded one girl and held a candle flame near her sister. Both flinched. They pinched the arm of one, and the other cried out in pain. The room grew tense, quills pausing mid-sentence. This was no trick of observation. Something unexplainable was occurring before their eyes. The physicians struggled to contain their excitement.

To them, the twins were proof of a phenomenon no textbook described, something that could make a man’s career if properly documented. But beneath their eagerness lay unease. Each test seemed to confirm that the twins shared more than resemblance. They shared perception, sensation, perhaps even thought.

And in an age when science was desperate to separate itself from superstition, the Callahan twins threatened to drag both realms together in ways no one dared admit aloud. The session ended in silence, the girls still holding hands as they were led back into the Dublin night. Yet every man in that room knew they had witnessed something extraordinary, something that would not be easily explained away.

And though none could yet imagine the consequences, the most disturbing discovery was still to come. The doctor’s curiosity could not be satisfied with mere observation. They wanted proof, tangible evidence that what they had seen was not some elaborate coincidence.

And so, in a chamber lined with glass jars and steel instruments, they drew the girl’s blood. Bridg protested at first, clutching her daughters tightly, but Michael urged her to relent. He had been told it was harmless, that a small amount would bring no danger. Reluctantly, she agreed, though she kept her hands clenched until her knuckles whitened. The first prick brought no tears.

The twins sat calmly, eyes steady, as the scarlet liquid flowed into the vial. But almost immediately, the room shifted. The blood did not behave as it should. One physician noted in his journal that it seemed sluggish, reluctant to clot, even as it collected in the dish.

Another whispered that under the lantern light, it carried an odd sheen, a faint glimmer that could not be explained by trick of flame. Some swore the color was wrong, not the deep crimson of human life, but some hing brighter, stranger, like diluted wine glowing in the glass. A younger student, unnerved, muttered about unholy taint. His words earned a sharp rebuke, yet no one could quite shake the feeling that what they were handling was not entirely human.

The blood was tested against that of other children, and every time it defied expectation, it resisted coagulation, spread thin and fast across surfaces, and in one account, later struck from official records, was said to flues faintly in darkness.

What unsettled the physicians most was not what they saw, but the realization of what it meant. If this were true, then the Callahan twins were not merely unusual in behavior. They were abnormal in their very essence. Their bodies did not obey the rules of nature. They were not curiosities. They were contradictions. The results were never published. In the official ledgers of the college, the entry was brief.

Specimens unsuitable, results inconclusive, but in private notes circulated, tattered, half-burned pages describing the sheen, the fluoresence, the refusal to clot, and with those notes came fear. Some urged that the findings be destroyed, that no trace remain to taint the college’s reputation. Others argued to study further, though their voices trembled as they spoke.

By the time the twins were led home that night, Bridg holding them close, the decision had already begun to form. The Callahan children were not to be discussed openly. They were to be remembered only in whispers hidden behind locked cabinets and sealed journals, for what the doctors had found was not a discovery they could celebrate. It was a truth they dared not speak.

It was a bitter winter night when the incident occurred, the sort of night when the damp air sank deep into bones, and the streets of Dublin lay cloaked in smoke and silence. The Callahanss had gone to bed early, their small home dark, save for the glow of a dying fire. But before dawn, screams shattered the quiet. Flames had erupted in a neighboring tenement, roaring through dry wood and thatched roofs, swallowing one room after another with terrifying speed.

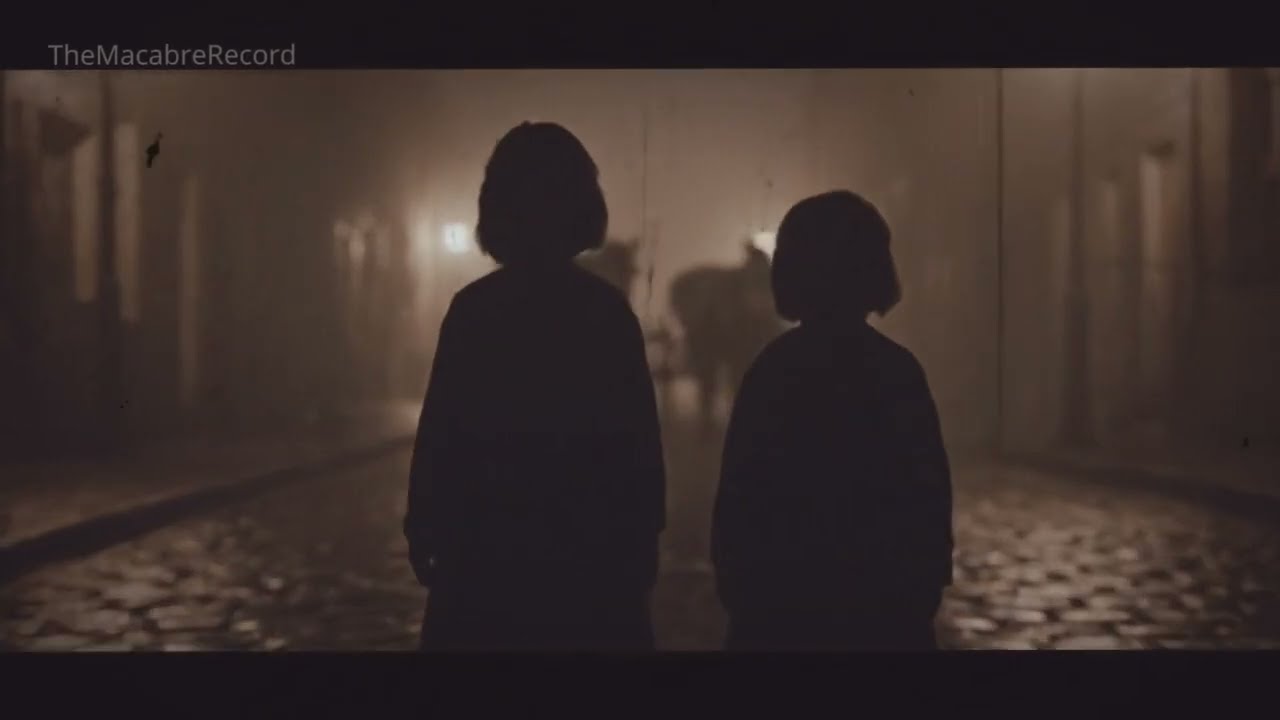

Neighbors rushed into the street, carrying children, dragging blankets, throwing buckets of water that hissed uselessly against the blaze. In the chaos, someone saw them. The Callahan twins standing perfectly still in the midst of the smoke. Their night clothes were singed, their hair blown wild by the heat. Yet their skin was untouched.

Witnesses swore the flames curved away from them, curling as though unwilling to draw near. While families fled, choking and blistered, the twins walked through the smoke as calmly as if they were stepping into morning fog. When their parents pulled them clear of the ruin, the crowd fell silent, every eye fixed upon the unburnt children. By dawn, the story had twisted into something darker.

People said the girls had caused the fire, that their presence invited it, that the inferno was not an accident but a sign. Mothers wept, fathers muttered of demons, and priests declared the event an unmistakable warning. Father O’Reilly, whose sermons had grown more dire each week, proclaimed to his congregation that only the UNH, only he could walk through flames unscathed.

God delivers no child from fire unless that child belongs to fire,” he thundered, and his words ignited a frenzy of fear. The doctors tried once again to calm the storm. They argued that shock and smoke might have blinded witnesses, that the girls were rescued quickly before burns could set in, but even in private, their voices wavered. Some of those same men had seen the children up close after the blaze, and could not explain how their hair bore the faint scent of smoke, while their skin showed not a single blister.

Notes written in haste described the phenomenon in dry clinical language, but the edges of those pages carried smudges where hands had trembled. For Dubliners, it was proof enough. The Callahan twins were no longer just oddities or cursed children. They had walked through fire and returned whole. And to a city balanced precariously between superstition and science, such a sight was not a miracle.

It was an abomination. The fire should have ended all debate, but instead it deepened the rift. Dublin was split in two. The common folk, who whispered of demons in the Callahan blood, and the men of science, who scrambled to explain away what had been witnessed.

Publicly, the physicians dismissed the accounts as hysteria, insisting the twins had been pulled from the blaze before harm could reach them. Articles in small journals spoke of exaggerations born from fear, assuring readers that nothing unnatural had occurred. But in private, the doctors stopped speaking of the Callahanss at all.

Their notes were quietly removed from lectures, their names avoided in conversation. It was as if the scientific world had decided in unspoken agreement that the twins did not exist. To acknowledge them was to risk ridicule or worse, accusations of heresy. For the Callahan family, the denial brought no relief. If anything, it left them more exposed. Neighbors who once offered bread now turned their faces away.

Bridg, who had tried to keep her daughters grounded in ordinary life, found even her oldest friends slipping into silence. Michael grew bitter, muttering that men in fine coats could lie with impunity, while his children bore the brunt of fear and hate. The twins themselves seemed untouched by the tension. They played together as always, speaking softly in their strange unison, their pale hands clasped even in sleep.

Yet there was an awareness in their eyes, a distant knowledge, as though they understood far more than they should. The church only pressed harder. Priests demanded that Michael and Bridg present the children for deliverance, though what that meant was never clearly explained.

Some spoke of exorcism, others of confinement in a convent where the girls would be hidden from the world. Michael refused, his voice trembling with rage, but his refusal only fed the whispers that the fams he had chosen darkness over salvation. As the months passed, the Callahanss retreated indoors, curtains drawn, doors barred.

They lived in uneasy silence, their isolation broken only by the occasional knock of a physician still brave enough or desperate enough to plead for another examination. But those visits grew fewer as well, for even the curious had begun to fear association. The family’s name became a warning spoken in taverns, a curse muttered in alleys. By denying them, science had hoped to erase the twins from memory.

Instead, the silence only made the mystery grow. For the less the city was allowed to know, the more its imagination filled the void with shadows. And in those shadows, the Callahan twins became something larger than life. Symbols of everything forbidden. Everything that should not be, yet could not be denied. Though the physicians had publicly abandoned the Callahan case, their fascination never truly died.

A handful of them, men whose curiosity outweighed their fear, continued their studies in secret. These meetings were held not in the grand halls of the college, but in dim back rooms lit by single oil lamps, where shutters were barred and voices kept low. Michael was bribed with promises of coin, told his daughters would come to no harm, though he must never speak of what was done.

Bridg, torn between fear and desperation, consented only because she believed refusal would invite worse consequences. It was during these clandestine sessions that the strangest findings emerged. The doctors, eager to test their theories of sympathetic bonds, turned to the new fascination of the age, electricity.

A small galvanic battery was brought into the room, its wires attached to rods and clamps. The idea was simple. Apply current to one child, observe whether the other felt it. The results, however, unsettled even the boldest among them. When the rod touched the arm of the first twin, her body convulsed with a sharp jolt.

Yet at that very instant, her sister cried out, jerking violently, though no wire had touched her skin. Again and again, the experiment was repeated. Each time both children reacted in perfect unison, as if the current flowed not through one body, but through both. Sweat beaded on the doctor’s brows, quills scratching furiously across paper.

Some muttered about a shared nervous system, though no such thing existed in medical theory. Others whispered of unseen forces, magnetism of the soul. Bonds that could not be explained by anatomy alone. Even the simplest shocks produced the same effect. A current passed through the hand of one twin made both hands tremble. A pulse delivered to a single leg caused both to kick.

And yet, when tested separately, each child’s body appeared whole and unremarkable. Their flesh bore no scars. Their organs sounded normal to the stethoscope. The contradiction gnored at the physicians. These were healthy children by every measure, yet bound together by something no science of the day could capture.

Bridg wept quietly during the experiments, clutching her rosary. Michael stood stiff in the corner, jaw clenched, though the sight of his daughters writhing together, left him pale and shaken. When the sessions ended, the girls walked home hand in hand as always, silent, their faces unreadable. But for the men who had witnessed their respose, nurses, silence was no comfort.

The Callahan twins were not just a mystery anymore. They were proof of something that should not exist. By the late 1830s, Dublin was sinking into hardship that no experiment or sermon could mend. Harvests had failed across much of Ireland, driving food prices higher than the poor could bear. The city’s narrow lanes filled with the stench of hunger and disease.

Bread riots broke out in the markets where desperate families begged for food while soldiers stood guard with rifles. In such times, fear needed a target, and the Callahan twins offered one. It began with muttered accusations. Some claimed that the girl’s presence brought blight to the fields, that their unnatural bond drained life from the soil.

Others swore that cows stopped giving milk if the twins were seen near the pasture. The livestock deaths of years past were dredged up again, retold with new horrors added each time until the story bore little resemblance to truth. When a fever swept through one parish, killing dozens of children, whispers insisted the Callahanss had been spotted walking the lanes the night before. The church did nothing to quiet the storm.

Priests desperate to reassert authority in a city wavering between despair and rebellion spoke of curses, of children marked by the devil, of sins that demanded purging. Their words were enough to ignite the desperate. Hungry families watching their infants waste away while the Callahan twins grew tall and strong, found in them an explanation more satisfying than fate or famine.

Better to believe two cursed children carried the blame than to accept the cruelty of nature. By 1839, hostility boiled into violence. Stones struck the shutters of the Callahan home with regularity. Doors were found smeared with ash. Crosses scratched into the wood as warnings. Men gathered in taverns, muttering that something must be done.

When Bridgette walked the market, sellers refused her coin, some even spitting at her feet. Michael fought back when he could, fists blooded from more than one brawl, but his defiance only deepened resentment. The twins, now old enough to sense the hatred around them, responded not with tears, but with silence. They clung to each other more tightly than ever, eyes watching, always watching, as though they knew what was coming.

On more than one occasion, neighbors swore they saw both girls standing at their window long after nightfall. Their pale faces lit only by the moon, their eyes unblinking. The city was unraveling. Hunger gnored at bellies, fear gnored at minds, and in the middle of it all stood the Callahan twins, no longer children in the eyes of Dublin, but omens of everything dark and merciless about the times.

And soon the anger that brewed in whispers would erupt in the open in a fury that no parent could protect them from. The breaking point came on a storm lashed evening in the spring of 1839. The wind howled through the alleyways, driving rain against the slate roofs, but the weather did nothing to quell the fury that had been building for months. A crowd gathered outside the Callahan home, their faces half-lit by torches, their voices rising in chance that twisted scripture into curses. Men shouted that the twins had brought sickness, that they had poisoned wells,

that they had walked untouched through fire because they belonged to it. Women wailed of dead infants, pointing trembling fingers at the shuttered windows. What began as a mob of dozens grew into hundreds. The narrow street heaving with bodies pressed shoulderto-sh shoulder. The sound of rage carried above the storm.

Inside, Bridg clutched her daughters to her chest, whispering prayers that slipped into sobs. Michael barred the door with what little furniture they owned, his fists bleeding from pounding on the table as though anger could build walls stronger than wood. The twins sat silently, their hands clasped, their faces eerily calm in the flicker of the oil lamp.

Some later claimed that when the mob’s cries reached their peak, the girls smiled faintly, as though they had been expecting this moment all along. The crowd hurled stones that shattered the windows. Torches were raised, threatening to turn the house into a p.

Then came the clatter of hooves and the flash of lanterns as the constabularary arrived, their shouts cutting through the chaos. Battons swung, dispersing the worst of the riers, though the fury did not subside. It merely scattered into the night, promising to return. The Callahanss were ordered out, escorted under guard through jeering crowds to a safer quarter. And then silence.

For a time it was said the family had been placed in protective custody. Others swore they had fled Dublin entirely, slipping away under cover of darkness to relatives in the countryside. But official records tell nothing. No parish ledger marks their departure. No census lists their names beyond that year.

It was as if the Callahanss had been erased in an instant, swallowed whole by the city that had turned against them. By morning, their home stood empty, its door hanging loose, its hearth cold. Neighbors gathered to stare at the abandoned rooms, whispering that the family had been spirited away, or worse, that the twins had dragged their parents into whatever shadowed place they themselves had come from.

The Callahanss were never seen in Dublin again. In the weeks following the Callahan’s disappearance, Dublin seemed to breathe easier, as though the absence of the twins had lifted some invisible weight from the air. Priests preached that evil had been driven out.

Neighbors congratulated themselves on surviving the ordeal, and families once again allowed their children into the streets. Yet beneath the relief lay something unspoken, a discomfort no sermon could erase. The Callahanss had not been punished, nor buried, nor even accounted for. They had simply vanished, and vanishing left too many questions unanswered. It was not long before stories began to surface beyond the city wall.

In Limrich, a farmer claimed he saw two pale girls standing at the edge of his fields at dawn, their hands entwined, watching him with the stillness of statues. In Kilkenny, a merchant swore that twins entered his shop together, spoke not a single word, then left without opening the door.

From Gway came tales of children who mirrored each other’s movements so perfectly it was as if the reflection of one had stepped out of glass to join her sister. None of these reports could be proven, but each carried details eerily consistent. The pale faces, the unblinking eyes, the way silence seemed to follow wherever they went. Such stories might have been dismissed as peasant fancies, the kind of ghost tales traded around firesides when the nights grew long.

But for a handful of men in Dublin, physicians whose notebooks still held the secret records of blood tests and electrical experiments, the rumors could not be ignored. They traveled quietly, avoiding attention, posing as itinerant doctors or scholars in search of folklore.

Their goal was not to comfort villagers, but to determine whether the Callahan twins still walked among the living. What they found was never shared in print. Letters between colleagues hint at interviews taken, observations made, but always the language trails off into vagueness, as if the truth itself was too dangerous to commit to paper. One doctor wrote only, “The reports are consistent. They are not gone. We must proceed with care.

” Another hinted darkly that their presence is wider than it should be, suggesting sightings in places so far apart that no human journey could explain them. The Callahanss may have vanished from Dublin, but they had not vanished from Ireland.

Their image lingered, flickering in rumor and testimony, like a shadow that slipped just beyond the lamplight. And for those who still believed in the power of evidence, the chase had only just begun. As months turned to years, the stories only grew more unsettling. Farmers, travelers, and inkeepers began reporting encounters that could not easily be reconciled.

In one village outside Cork, a school teacher claimed that two pale girls appeared at the edge of his classroom window, their faces pressed to the glass, though no footsteps marked the mud below. That same day, miles away in Tullmore, a widow swore she had given bread to two silent children, who mirrored one another’s movements with eerie precision.

Both accounts were dated and sworn, yet separated by a distance the girls could never have crossed in the same span of hours. Soon such contradictions multiplied. In Kerry, two fishermen described seeing the twins standing on a cliff above the sea, their night clothes fluttering in the wind, unmoving as waves crashed below. Yet in Waterford on that very evening, a constable reported leading away a pair of girls matching their description after they were found wandering near the docks. When challenged, he admitted the children had left no record in custody.

They had simply vanished before morning, leaving only confusion in their wake. The idea of duplication began to creep into whispered conversation. Some villagers believed there were not two girls, but many copies of the Callahanss walking the breadth of Ireland, each as real as the last.

Others muttered of fairies, changelings left to mock humanity by showing us faces we recognized where none should be. A few, clinging to scraps of rationality, suggested imposters, children dressed alike to frighten the gullible. But even they struggled to explain the consistency of the details, the mirrored gestures, the unblinking eyes described in every account.

The physicians who still pursued the twins grew increasingly cautious in their notes. References to simultaneous presence and geographic impossibility littered the margins of their journals, always written in nervous shortorthhand, as if even the act of spelling out the truth might invite danger. One doctor confided in a letter that he feared the girls were not bound by natural laws of distance or time, but by something else entirely, something science had no language for.

For the Irish common folk, such mysteries needed no language. They told and retold the stories until the Callahan twins became less children than legend, wandering figures who could appear wherever fear was greatest. But behind the folklore, behind the trembling voices, lay a darker question that no one dared ask aloud.

If the twins could appear in two places at once, how many of them might truly exist? By the early 1840s, the whispers had reached such intensity that Dublin’s officials attempted a solution not of faith, nor science, but of bureaucracy. Records surfaced in the city registry declaring the Callahan twins deceased.

Their names, written plainly, though curiously misspelled, were listed alongside a date of death and a brief cause. Consumption. To the casual eye, it was unremarkable. In a city drowning in illness, children’s deaths were recorded daily with little ceremony. Yet to those who knew the family, something was deeply wrong. The handwriting on the certificates did not match the registars’s usual script.

The signatures of witnesses were scrolled in hands unfamiliar to anyone in the parish. Even the date raised questions entered weeks after the supposed deaths at a time when sightings of the twins were still being whispered across the countryside. For men accustomed to ink and ledgers, the inconsistencies were glaring.

To others, it was confirmation that the city wished only to close the book on a story that had become too dangerous to leave open. News of the certificate spread quickly. Some rejoiced, convinced the children had at last been laid to rest and their curse lifted from the land.

Priests used the announcement to soothe their congregations, declaring that God’s will had prevailed. But in taverns and markets, men shook their heads. “Dead,” they muttered. “Then who are the girls we keep seeing? For in the same week the certificates were issued, a farmer outside Carlo swore two identical girls had wandered his fields at twilight, their white dresses glowing in the half light before vanishing into the mist.

The physicians who still kept secret records reacted with alarm. One in a letter preserved only in fragments wrote, “They are not dead. The papers are a fabrication. Why the deception unless someone fears the truth?” Another crossed the rough entire pages of his journal, replacing them with the simple line, “The matter is closed.

” But his handwriting trembled, betraying anything but closure. For Bridg and Michael, if they still lived, the certificates were more than insult. They were erasia. It was as if their daughters had been scrubbed from the city’s memory by a few strokes of a quill. No funeral was ever recorded. No burial plot ever marked. The twins supposed deaths existed only in ink, a flimsy veil draped over a mystery that refused to stay hidden. What remained was worse than absence.

Officially, the Callahan twins no longer existed. Unofficially, their shadows stretched across Ireland, multiplying in stories, appearing where no child should be. And those who questioned the papers most fiercely began to realize the truth.

Someone wanted the world to forget the Callahanss, no matter how many lies it took. The discovery came not from physicians or neighbors, but from the brittle pages of a parish diary found decades later in a trunk of forgotten papers. It belonged to Father O’Reilly, the same priest whose sermons had thundered against the Callahanss, though what he wrote in private was far darker than anything he dared speak from the pulpit.

His entries began cautiously, notes of visits to the family, remarks on their odd behavior, but soon swelled into confessions of fear and dread. “These are not children,” one passage read. “They are mirrors of one another, reflections given flesh, and no baptism can cleanse what was never of God.

” The diary spoke of meetings behind closed doors, where higher church officials from Dublin and even further a field pressed for action. O’Reilly claimed he was ordered not to exercise the twins, but to monitor them, to document their lives until the day came when decisive measures could be taken. “We are instructed to observe only,” he wrote in a trembling hand.

“And yet I cannot silence the conviction that observation is not enough. Each day they live, the danger grows.” One particularly unsettling entry described a visit to the Callahan home. O’Reilly claimed the girls stared at him without blinking, their voices rising together in a question he swore he had never spoken aloud.

They answered the thought in my mind, he wrote, as though they drank it from the well of my soul. I fled before they could take more. Another passage recounted the fire, insisting the twins had not been spared by God’s mercy, but sustained by a force opposed to it. “Flame is their element,” he scribbled. They belong to it as fish belong to water.

Most disturbing of all was a single line underlined twice that seemed less diary than confession. We have been warned from Rome itself. These children must not be permitted to endure. The entry gave no further detail, no names or dates, only the chilling implication that the twins existence was known beyond Ireland. their fate discussed in corridors of power far from Dublin’s slums.

The diary ended abruptly in 1839, the final page stained and torn as though ripped away in haste. Whether Father O’Reilly destroyed the rest himself, or it was silenced by another hand, no one could say. But what remained was damning enough. proof that the church had not only feared the Callahanss, but had marked them long before the mob ever gathered outside their door as souls too dangerous to be left in this world.

If the church had moved in secrecy, the city ace medical institutions acted with a colder efficiency. By the early 1840s, any official mention of the Callahan twins had begun to vanish from the Royal College of Surgeons. The process was not announced nor recorded, but carried out quietly, like a sickness being cut away before it spread.

Students who had once taken notes on the twins examinations returned to their lecture halls to find entire shelves empty, pages missing from anatomical collections, diagrams ripped neatly from binding. Professors spoke less and less of the case until at last they spoke of it no more. It was as though the children had never existed.

But behind the polished doors, rumors swirled. Some claimed the decision came from London, where the college’s reputation mattered more than truth. Others whispered it had been ordered after a private demonstration in which the twins responses unsettled even the most hardened physician.

The galvanic tests, in particular, were said to have left senior scholars shaken, their faces pale as they argued late into the night over whether they had witnessed physiology or heresy. One student later recalled hearing a professor mutter that the devil himself could not have devised such symmetry, though the remark was stricken from any surviving account.

A handful of lecturers resigned during that period, men whose careers had barely begun. Their departures were sudden, their names struck from rosters without explanation. In letters that survived, one wrote, “The truth must be buried, else it will bury us all.” Another confessed he feared for his soul more than for his profession, warning that continued study would invite damnation under the guise of curiosity.

The purge was so thorough that by midentury new students entering the college heard nothing of the Callahanss. Only whispers remained in the halls, traded like contraband by those who had once glimpsed the experiments. The official narrative was silence, and silence became the only shield against scandal.

Yet silence did not erase memory. Among the older physicians, eyes darkened whenever the subject arose, and hands trembled over pens, as if writing too much might betray them. Those who had been closest to the girls seemed least able to let them go. One even sketched their faces again and again in the margins of unrelated notes, unable or unwilling to banish their image.

The purge achieved what it set out to do, to erase the Callahan twins from the annals of science. But in erasing them, the college only deepened the mystery. For if the twins were merely children, why such effort to pretend they had never lived? And if they were not, then what had those men seen that frightened them enough to surrender truth for silence? Among the whispers that survived the purge, none was more unsettling than the one that lingered in the anatomy halls.

Students spoke in hushed voices of cadaavvers wheeled in under cover of night, bodies no one dared record, and dissections performed behind locked doors. According to rumor, the Callahan twins had not simply disappeared from Dublin.

They had been taken into the very heart of the college, their fate sealed on the cold steel tables where so many nameless porpas had been cut open before them. The evidence was thin but persistent. In a ledger of anatomical specimens, two entries had once been marked in ink, only to be scratched violently away until the paper tore. In another book, a marginal note survived.

Identical subjects preserved but unfit for demonstration. No date, no names, only the faint suggestion that something extraordinary had been studied, then deliberately erased. Students who later poured over the archives found gaps where records should have been, gaps that aligned eerily with the year of the Callahan’s disappearance. Yet the most disturbing fact was this. No physical remains were ever logged.

The college was meticulous in preserving specimens from diseased organs to malformed skeletons. Jars lined the shelves, each labeled with date and origin, each a testament to the college’s pursuit of knowledge. But of the Callahanss, nothing remained. No bones, no tissue, no record of burial or cremation.

If they had been dissected, as rumor claimed, then their bodies had either been destroyed completely or hidden so carefully that no trace could be found. Some insisted the professors feared to keep them, believing the girl’s flesh itself carried corruption. Others believed the twins survived the attempt, spirited away before the college could complete its work. The stories conflicted, but the unease was the same.

What should have been a clear answer, only deepened the mystery. Even among the skeptics, the silence was damning. One professor years later admitted in private that he had heard the cries of two children echoing through the college halls one night followed by the sudden hush of doors closing. “If they were dead,” he whispered. “Then why did I hear them weep?” The anatomy rumor was never confirmed, never written in any surviving document, but its persistence passed from one generation of students to the next, became a ghost of its own. For if the Callahanss had indeed been taken apart, their absence from the jars

and shelves of the college raised a question more terrifying than any haunting. Where did their bodies go? With no records to hold them and no graves to contain them, the Callahan twins slipped easily from history into legend. Dubliners, hungry for stories to explain the unease that lingered long after their disappearance, began to tell tales that blurred memory with fear.

By the 1850s, the girls were no longer spoken of as children, but as spirits that still walked the city’s fogladen streets. Some swore they saw them in the liberties on moonless nights, standing at the corners of alleys where gaslight struggled to reach, their hands clasped, their eyes unblinking.

Others claimed the twins appeared at windows of tenementss where children lay sick, watching silently until the fever took its course. Cab drivers told of late fairs. Two identical girls who entered their carriages without a word rode through the mist, then vanished before payment could be asked. Always they were described the same, pale, still, their movements mirrored as if the one were shadow to the other.

The fire incident became the centerpiece of folklore. Storytellers insisted the girls had not been spared, but had been born of flame itself, wandering eternally with the smoke of that night, clinging to their hair. Mothers frightened their children with warnings. Behave, or the fire twins will come, untouched by heat, to stare at you until your breath runs cold. Even skeptics admitted the tales carried power.

Something in Dublin seemed unwilling to let the memory die, no matter how hard the college and church tried to erase it. The stories spread beyond the city. In rural villages, travelers spoke of encountering the twins on roadsides, watching silently as carts creaked by. Sailors leaving the Dublin docks claimed to see two figures standing on the pier, their dresses fluttering in a wind that touched no one else. In each retelling, details shifted, but the core remained.

Two girls always together, always silent, their presence a herald of something dreadful. For the ordinary people of Ireland, the Callahanss became less a scandal than a warning. To speak of them was to invoke the uncanny, the thin line where faith, science, and superstition all failed to explain.

And though the men of learning tried to bury the case under silence, the stories took root in places no purge could reach, in the mouths of children, in the whispers of taverns, in the prayers muttered at night when footsteps echoed on empty cobbles. Thus the Callahan twins became not merely a forgotten family’s children, but phantoms of Dublin itself, reflections walking its streets long after their bodies were gone. As folklore blossomed in the streets, the halls of science grew colder still.

By the mid-9th century, the Callahan twins had become a subject not of curiosity, but of prohibition. In London, where the royal societies set the tone for medicine across the empire, the very mention of the mirror case was enough to sour a discussion.

Professors who hinted at it were interrupted, their lectures redirected to safer ground. Young physicians who raised questions were warned, sometimes harshly, that they risked their reputations if they pursued the matter further. The twins, it seemed, were not to be debated, but buried publicly. The justification was simple. No evidence remained.

Dublin’s college had no specimens, no ledgers, no published findings. Without proof, there was nothing to study. But privately, letters between scholars betrayed a deeper fear. Some admitted the accounts were too consistent to be dismissed entirely. Yet to speak of them was to invite ridicule from peers or suspicion from the church.

Better, they reasoned, to deny that the children had ever lived to tangle with a case that threatened the fragile boundaries between faith and science. In medical journals of the 1850s, one finds only faint traces, cryptic references to unsubstantiated claims from Ireland, or footnotes warning readers against unreliable testimony of hysterical witnesses. No names were given, no details supplied.

It was as ifmies were rewriting history in real time, sanding away every splinter that might remind the world of the Callahanss. By the 1860s, the erasia was complete. Ask a London physician about the case, and he would likely frown as though you had spoken of fairy tales. Yet silence is not the same as forgetting.

In private, men still muttered of experiments half-finished, of results never explained. The purges had done their work too well, leaving gaps where knowledge should have been, and into those gaps poured speculation. Could two minds share one consciousness? Could one body echo the pain of another? Such questions haunted the edges of legitimate science, their answers left deliberately unspoken.

The Callahan twins had thus become a paradox. In Dublin, they lived on as phantoms in folklore. In London, they survived only as absence, a ghostly silence where their names should have been. Between the two, truth was crushed, squeezed out by fear on one side and shame on the other. And in that silence, the sinister case of the Callahanss slipped further from fact into me, leaving only the faintest echoes for the next generation to find.

For decades, the Callahan twins lived only in whispers, half forgotten in parish tales and academic silences. But in the 1870s, their story threatened to resurface. A Dublin journalist named Thomas Keating, known for his taste for scandal and forgotten histories, stumbled upon fragments while combing old parish ledgers.

He found a birth record smudged nearly beyond legibility, and beside it a curious gap in baptismal lists that no registar could explain. From there he chased further into the halfb burned diary of a physician into tavern accounts that still spoke of the fire twins and at last into the hidden margins of father O’Reilly’s diary recovered from a chest of discarded papers. Keating published his findings in a small but daring periodical.

The article titled the children science feared to name was less accusation than reconstruction. He wo the stories together. Birth in 1838, rumors of fire and blood vanishing without a trace, and concluded that something extraordinary had been erased. If such children lived, he wrote, then Ireland is poorer for the truth we were denied, and darker for the silence that replaced it. The peace caused a stir.

In the streets readers murmured of ghosts and curses, delighting in the revival of an old legend. But in the halls of authority, the reaction was swift and severe. The church denounced the article as blasphemy. The college issued a formal statement that no such children were ever studied in Dublin, branding the story the work of liars and fantasists. Within weeks, Keiting’s magazine was seized.

Its presses shuttered by order of officials who cited public indecency and superstition. Then Keiting himself vanished from public life. Some claimed he fled the city, ruined by debt and disgrace. Others whispered darker endings, that he had been silenced for daring to pull at threads better left untouched. His body was never found, though years later a set of bones was discovered in a collapsed cellar on the outskirts of Dublin, identified by some as his.

Whether accident, suicide, or something more deliberate, no one could say. What remained of his article survived only in fragments, torn pages hidden in collections of folklore. Yet those fragments were enough to keep the Callahan story alive, a reminder that even attempts to erase the past can leave traces. And for those who read his words, the question lingered like smoke.

What truth had Keiting uncovered that frightened men so much they chose to silence him forever? By the close of the 19th century, the Callahan twins were no longer spoken of as children at all, but as something other, something outside the boundaries of ordinary life. In taverns and at firesides, the fragments of their story were retold with new urgency.

Each detail shaped into evidence that the girls had never belonged among men. The fire was the most often repeated. Two children walking unscathed through flames while others burned. To some it proved divine protection, but to most it was a mark of the infernal. Born of fire, belonging to fire, people muttered, the tale hardening into certainty with every retelling. The blood became another cornerstone of the legend.

Physicians had never published their findings, but their journals had leaked enough to give fuel to rumor. Blood that glowed under lamplight, villagers whispered, that flowed without clots, that spread like water yet did not fade. What began as cautious medical description became folklore of its own. Blood that was not human at all, blood that carried a pow, and no sacrament could cleanse.

And always there was the mirroring, the uncanny way the twins moved as one, spoke as one, even seemed to think as one. What had unsettled physicians became in the mouths of common folk a mark of possession? Two bodies, one soul, the story went. But whose soul and from where? Children were hushed when they laughed in unison.

Mothers crossing themselves nervously if siblings finished each other’s sentences. The Callahans had cast their shadows so deeply that even ordinary twinship became suspect in some corners of Ireland. Each piece of the story, fire, blood, mirroring, was woven together until it formed something larger than memory, something closer to myth. No longer were the Callahans described as unfortunate girls shunned by fear. They were spoken of as proof.

Proof that the world contained things science would not name, that the church dared not confront, that ordinary men and women could only whisper about in dread. Yet beneath the folklore, a subtler truth lingered. Those who dug into parish ledgers and halfburned notebooks saw a pattern too deliberate to be dismissed.

The erasers, the forged certificates, the vanished specimens, all of it suggested not invention, but concealment. The twins had lived, and what they revealed had been so unsettling that powerful men chose to bury the truth beneath lies. And if they had truly been erased, then the question became more chilling still.

Why erase what was harmless? The answer spoken in taverns and whispered in churches was the same. Because the Callahan twins were never merely children. They were something else. Something no one wanted to admit had ever walked the earth. In the early decades of the 20th century, when the appetite for the strange and unexplained surged across Europe, the Callahan twin story was briefly reborn.

Folklorists, medical historians, and the newly formed psychical societies all caught wind of the fragments. Old parish notes resurfaced. O’Reilly’s diary was cited in private lectures, and faded testimonies were gathered from the grandchildren of Dubliners who had once claimed to see the twins. To these investigators, the Callahanss represented a perfect crossroads, a case rooted in history, yet so strange it defied both medicine and religion.

In 1908, a team from the Society for Psychical Research quietly visited Dublin to collect what they could. They spoke to aging parishioners who remembered hearing their parents’ hush tales of the fire twins. They tracked down one of Keiting’s surviving pages yellowed and half torn, which described the blood that shimmerred like no other.

They even claimed to find reference to an unmarked burial plot outside the city, though when they sought to exume it, no records could confirm who lay beneath the soil. Their report, circulated in draft form, concluded cautiously. The Callahan twins, if real, represent a phenomenon for which we have no classification.

But just as quickly as the case reemerged, it slipped away. The draft report never saw publication. Researchers complained that pages vanished from archives, diaries disappeared from trunks, and informants withdrew their statements. One professor claimed he had transcribed a full letter from a physician who had studied the girls only to find the original missing when he returned to collect it.

Another incy that his notebooks were stolen from a locked drawer. Skeptics dismissed these complaints as clumsiness yet the pattern was too consistent to ignore. By midentury the Callahans had become a curiosity for fringe circles alone. Paranormal investigators included them in compendiums of Irish hauntings, describing them as ghostly figures who walked in unison through the liberties.

Medical historians, when pressed, admitted they had heard rumors, but refused to comment further. Each attempt to bring the twins back into the light, ended the same way, with missing records, broken chains of evidence, and warnings, sometimes stern, sometimes veiled, that the matter was best left in the past.

For the new generation of researchers, the question shifted. Were the twins themselves the mystery? Or was the true puzzle the way history seemed determined to erase them? Either possibility was chilling. For if the Callahans still walked in some form, then the old fears were true.

And if they did not, then someone or something still labored to keep their secret buried. It was in the 1960s, more than a century after the Callahanss had vanished, that one final trace surfaced. An archivist at Trinity College Dublin, cataloging a collection of neglected papers from the Royal College of Surgeons, stumbled upon a packet bound in twine, and hidden within the spine of an unrelated ledger.

Inside were only a handful of pages, tattered, water stained, many illeible. But among them lay a single entry that froze the archavist’s blood. It was not a full report, nor even a diary, but a memorandum hastily scrolled in a physician’s hand. The date was smudged, though the year 1839 could still be read.

At the top, the heading case Callahan. Below a series of broken sentences, identical beyond measure, reflexes, simultaneous, blood irregular, light under flame, and then at the bottom, a line that seemed less medical note than judgment. They are not of science. No explanation followed.

No signature was attached, though a faded initial, possibly M, lingered in the corner. The memorandum gave no answers, only confirmation that the twins had indeed been studied, and that those who studied them had recoiled from what they found. The archavist, Shaken, filed the pages into a restricted collection, where they were eventually marked as miscellaneous and buried among hundreds of unrelated documents.

When word of the find leaked, a handful of researchers pressed for access. Most were denied, told the material was too degraded to be of value. Those who managed to glimpse the fragments reported that some words had been deliberately scratched out, as if someone long ago had tried to obliterate the record. The surviving phrase, “They are not of science,” was repeated in lectures and articles, always met with skepticism, always dismissed as either fraud or misinterpretation. Yet to those who had followed the story for decades, it rang with a dreadful

finality. If the twins were not of science, then what were they? Spirits clothed in flesh, a curse made visible, or some anomaly that cut across the fragile boundary between the natural and the supernatural? The memorandum did not say, and perhaps that was the point. By refusing to classify them, the physicians had consigned the Callahanss to the only place they could safely exist, the Shadows.

And so, more than a century after Dublin’s streets had last whispered their names, the twins emerged once more, not in flesh, but in ink. A final reminder that they had lived, had been studied, and had left behind a question that no science dared claim as its own. Even now, nearly two centuries after their birth, the Callahan twins linger in Dublin like a shadow that will not lift.

Walk the Liberties on a mist heavy night, and you will still hear the whispers. Two pale girls seen beneath a street lamp, hands entwined, their steps so perfectly mirrored that it seems no mortal breath could separate them. Cabmen refuse fairs along certain streets after dark, muttering that they will not risk seeing the faces that appear in their carriage windows without doors ever opening.

In taverns, old men tell younger ones that the fire twins are not gone, only waiting, their silence heavier than words. Science has long since turned away. The college keeps no records. London refuses to speak their name, and every attempt to reopen the case ends in vanishing notes. misplaced files or sudden silence.

The church too avoids the subject, its priests speaking of sin and redemption, but never of the children once marked for eraser. Yet the silence itself has become its own kind of confession. For why should so many labor to bury what was harmless? Why strike out pages, forge certificates, purge records, unless the truth was more terrible than the lie? The fragments that remain, the diary entries, the whispered testimonies, the single surviving memorandum form a pattern as chilling as it is incomplete.

Two children born in Dublin in 1838. Two children who moved as one, spoke as one, felt as one. Two children who walked through fire, whose blood shimmerred under flame, whose very existence unsettled priests and physicians alike. And then, just as suddenly, two children erased, as though by speaking their names, the city feared it might summon them again.

Perhaps they died. Perhaps they lived on in exile, their story twisted into myth by distance and time. Or perhaps the truth is stranger still, that the Callahanss were never ours to begin with, that they slipped through Dublin like a reflection crossing a mirror, leaving behind only the memory of their passage.

Stand in the liberties tonight when the fog is thick and the lamps burn low, and you may hear it, the sound of two pairs of footsteps falling in perfect rhythm, never quite out of sync. Some swear that if you turn to look, you will see them waiting at the end of the street, hands clasped, eyes fixed, silent as ever.

And if you do, pray they are only watching.

News

Single Dad Was Tricked Into a Blind Date With a Paralyzed Woman — What She Told Him Broke Him

When Caleb Rowan walked into the cafe that cold March evening, he had no idea his life was about to…

Doctors Couldn’t Save Billionaire’s Son – Until A Poor Single Dad Did Something Shocking

The rain had not stopped for three days. The small town of Ridgefield was drowning in gray skies and muddy…

A Kind Waitress Paid for an Old Man’s Coffee—Never Knowing He Was a Billionaire Looking …

The morning sun spilled over the quiet town of Brier Haven, casting soft gold across the windows of Maple Corner…

Waitress Slipped a Note to the Mafia Boss — “Your Fiancée Set a Trap. Leave now.”

Mara Ellis knew the look of death before it arrived. She’d learned to read it in the tightness of a…

Single Dad Accidentally Sees CEO Changing—His Life Changes Forever!

Ethan Cole never believed life would offer him anything more than survival. Every morning at 5:30 a.m., he dragged himself…

Single Dad Drove His Drunk Boss Home — What She Said the Next Morning Left Him Speechless

Morning light cuts through the curtains a man wakes up on a leather couch his head is pounding he hears…

End of content

No more pages to load