“THE SCAR THAT SUMMONED 250 OUTLAWS: Girl Repairs Biker’s Harley, Revealing the FRESH WOUND Her Stepfather Gave Her. The Hell’s Angels’ VENGEANCE Ride Began 3 Days Later.”

When eight-year-old Violette handed the Hells Angel the wrench back and said, “Your motorcycle is repaired, Mr.”, the man looked down at the scar that ran from her temple to her jaw. It was pink and fresh, the kind of wound that comes from glass and anger, not a fall or bad luck.

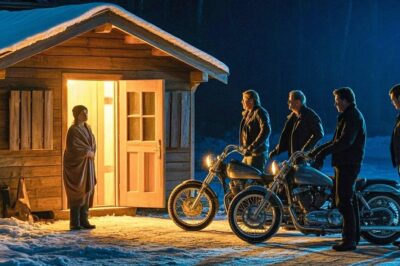

“He asked her who had done that to her.” She lied and said, “She fell.” He didn’t press, not yet. Three days later, two hundred motorcycles surrounded a house in Millbrook, the man inside believed he was untouchable. “He was wrong, because what he had done to this little girl in the darkness of his own home was about to be dragged into the light.” “The brothers don’t forgive. They don’t forget. They were on their way to him.”

Millbrook, Pennsylvania, sits in a valley carved by an old river and the passage of time. The Main Street has two traffic lights, a diner that serves breakfast all day, and a hardware store run by the same family for four generations.

Kids ride their bikes until the streetlights come on. Church bells ring on Sundays. “It’s the kind of place where people bring casseroles when someone dies, and gossip travels faster than the mail.” Autumn had settled like a quilt, spreading layers of rust and gold.

“And the air carried that crisp promise that winter wasn’t far off.” In a town so small, everyone knows everyone else’s business, the good and the bad. Even if they pretend they don’t. On the eastern edge of town, where the asphalt turned to gravel and the houses stood further apart, sat a small Cape Cod house with peeling white paint and an overgrown yard.

The mailbox read Corbett now, but beneath the peeling paint you could still make out the faint outline where Brenner had been. Daniel Brenan had built that house with his own hands and ran his small engine repair business out of the detached garage.

“If you walked into that garage blindfolded, you’d know where you were just by the smell. Motor oil, old gasoline, metal shavings, and the light, sharp smell of rubber.” Daniel had loved his work. He had loved his daughter, too. He let her stand beside him at the workbench, holding screws and handing him tools, even before she could read the numbers engraved on the sockets.

“Those afternoons with him were Violette’s earliest memories, his large hands guiding hers, his patient voice explaining how carburetors mixed air and fuel, how spark ignited motion.” “He never raised his voice, never lost his patience. He told her she had a gift, that some people just had a feel for machines. It was in her bones.”

Then Daniel was crushed between a forklift and a loading dock at the steel mill. One moment he was humming along to the music on the radio while tightening an engine, and the next, his life was over. The neighbors brought casseroles. The church ladies cried for Violette. Violette was too young to understand that the ground beneath her feet had shifted forever.

She only knew that her father’s tools were now silent and her mother started staring at walls. The weight of grief, hospital bills, and funeral costs pressed down like a heavy hand on the little house. Into that void stepped Randall Corbit.

He was a foreman at Henderson Construction, broad-shouldered, square-jawed, with a firm handshake and a habit of calling everyone “Sir” or “Ma’am.” He went to church on Sundays. He donated to the fire department raffle. He coached Little League in the spring. To the world, he looked like stability. To a widow drowning in debt and loneliness, he looked like salvation.

“They married within a year of Daniel’s death.” People whispered about the speed but quickly added, “She deserved some happiness.” No one asked what kind of happiness was being rationed behind closed doors. It started with criticism, “why dinner was burnt, why the laundry was piling up, why Violette was so loud.”

“It moved on to control, what she wore, who she spoke to, when she went to bed.” He didn’t like the way Violette looked at him, those gray eyes that saw too much. He didn’t like how she disappeared into the garage, into Daniel’s world. “He said it was strange, for a little girl, to be so interested in machines.”

He wanted her to play with dolls. Violette tried to comply, but the garage called to her. “It was the only place in the house that still felt like home.” The pegboard where Daniel had hung his tools remained untouched, every wrench exactly where he had left it. The drawers in his red rollaway box slid smoothly.

There was an oil stain on the concrete shaped like a heart. She sat on an old upturned bucket, taking apart broken toasters, rummaging through the insides of discarded weed-whackers from the dump, cleaning carburetors until the brass jets shone like new.

In those hours, she could almost hear Daniel humming along to the radio again. Randall saw it as defiance. His patience wore thinner with each month. He started making rules about where Violette could be. He didn’t like her outside unsupervised. He didn’t like her checking out “boy books” from the library. “He said he was protecting her.” “He said he was a good father.”

And she believed him, wanted to believe him. “Because the alternative, that she had brought a monster into their home, was too much to bear.” The first time he hit her, he cried afterward. “He’d been drinking,” he said, “he’d had a hard day at work. Dinner was cold. The stress got too much.” “He promised it would never happen again.”

He bought her flowers. He wrote a note, and Violette, her self-worth eroded by grief and exhaustion, accepted his apology. The next time happened because Violette left her backpack by the entryway and he tripped over it.

He shoved her so hard she got a bruise. He blamed his anger on the pain in his shin. “He laughed later.” “He told her to toughen up.” She told herself, “It wasn’t a pattern, it was a bad day.” She was wrong. Violette learned rules to survive. “Be small, be quiet, be invisible. Don’t leave your toys out.”

“Don’t interrupt. Don’t make noise when he’s watching TV. Don’t answer questions unless you’re asked.” The garage became her sanctuary. Her hands grew calloused and quick. She could feel the subtle roughness of a faulty bearing, hear the quiet hesitation of a misfiring cylinder. Her father’s voice echoed in her head: “Listen to the machine. It will tell you what it needs.”

“When she brought home the failing grade in math, she didn’t expect the explosion.” She had always been good at math, at spatial relations, at understanding how parts fit together. But fear robbed her of concentration.

She had been awake half the night, listening to Randall and her mother argue, counting the footsteps pacing the hall, wincing at the sound of clinking bottles. She couldn’t focus on decimals and fractions. The note from the teacher asked for a parent conference. Randall caught her in the kitchen, a beer in his hand. His eyes narrowed. “He accused her of not trying, of being lazy, of embarrassing him.”

He didn’t see Violette’s eyes dart to the doorway, looking for an escape. The bottle left his hand almost before he registered that he had thrown it. “Time slowed for Violette.” She saw the brown glass turning, saw the liquid inside shimmer amber, saw the jagged mouth aimed at her. She turned her head.

The bottle exploded against her cheek. Pain bloomed bright and hot. “The world went white, then red.” “She tasted blood, she didn’t scream, she had learned silence.” Her mother covered her mouth, stifled a cry, then dropped to the floor, pressing a dish towel against her daughter’s face and whispering, “It was an accident.”

“Tell them: ‘You fell.’” At the hospital, the nurse cleaned the wound, looking at her with knowing eyes. “What happened?” she asked softly. “She fell off her bike,” her mother said. “too fast.” Violette nodded. The nurse didn’t believe them, but without a confession, there was nothing she could do.

Violette left with seven stitches and a scar that would etch itself into the town’s memory. After that, Violette stopped talking at school. Teachers noticed the change. The school counselor called once, but Randall answered and said, “Everything was fine.” The Sheriff was called twice to check on the welfare.

He knocked on the door, accepted Randall’s calm tone and the tidy living room, and left. “He never asked if he could see the garage or the bruise on Violette’s back where Randall’s boot had caught her.” Randall knew exactly how far he could go without drawing an indictment.

The bruises were in places clothing covered, the insults happened behind walls. The terror was hidden in the way Violette’s shoulders hunched when he entered a room. The library was her other safe place. Mrs. Henderson, the librarian, commented neither on the scar nor the dark circles under her eyes. She simply showed Violette the section for mechanical engineering and let her sit cross-legged in the aisle, tracing diagrams of pistons and crankshafts with her finger.

The library smelled of dust and paper. a comforting contrast to the sharp smell of the garage. It was quiet, save for the fluorescent light humming and the occasional whisper. Violette took the long way to and from the library, three miles along Route 9, because it meant fewer houses, fewer questions, less opportunity for someone to see the mark on her face and ask.

She carried her father’s pocketknife in her backpack, though she wasn’t sure what she would do with it. It felt like a talisman. This Saturday, the October sun was warm enough that she pushed her sleeves up. The trees along Route 9 were a blaze of orange and red.

The sound of a V-twin engine broke through the afternoon. A deep, pulsing rhythm. Violette smiled despite everything. She loved the sound of motorcycles, especially Harleys with their uneven idle and deep growl. She turned as the bike came into view. It was a Fat Boy, black and chrome, its tailpipes cut low and wide.

The rider was tall, wearing a leather vest with a patch on the back that made Violette turn cold. She knew what that symbol was. Everyone in Pennsylvania knew it. Hells Angels. “You didn’t mess with them.” “They weren’t friendly.” Randall had said that when they rode through town last summer. “Stay away from them. They’re criminals.”

But here was one of them. Rolling to a stop. His machine coughed and died. “Is everything alright?” Violette asked before she could stop herself. The biker swung his leg over the seat, stood, and looked at the engine like it had betrayed him. He was late 40s with weather-beaten skin and grizzled hair in a close-cropped cut.

His leather vest, the “Cut,” had three pieces. The top rocker read “Hell’s Angels.” The center patch was the winged skull, known as the Death Head, and the bottom rocker read “Pennsylvania.” On his chest was a small rectangle that read SGT at Arms. He looked at the little girl with dirt under her fingernails and the scar on her face and weighed her offer. He should have sent her away, but his pride was hurt. His bike wouldn’t start. “You know anything about Harleys?” he asked, half-joking, half-hopeful.

Violette nodded: “My Dad taught me.” For a moment, Reaper (Markus Donovin) saw the ghost of Daniel Brenan standing behind his daughter at the gas pump, handing him a wrench. Reaper’s own father had left when he was young. The club had raised him.

He knew what it meant to find family where you could. He handed the girl his multimeter. She tested components with hands too small for the tools but as steady as any mechanic’s. She traced the wiring, found the loose connection, and jumped it with a paperclip.

When the engine roared back to life, Reaper’s grin was genuine. “You just saved me from pushing this beast ten miles,” he said. He offered her money. She declined. “Just help someone when you see they need it,” she said. She pulled her hood up and turned away. Reaper was just swinging his leg over the The person he called was his President, Garret E.

“Smoke Finlei.” Smoke had two tours in Vietnam before joining the club. He commanded respect the way a veteran does, quietly but undeniably. Reaper told him about Violette. Smoke didn’t ask if she was lying. He didn’t ask if they should interfere.

He asked, “Where?” When he heard Millbrook, he said, “We’re coming.” Reaper then called the Sergeants at Arms of the nearby charters. Steel City in Pittsburgh, Lake Area in Cleveland, Liberty Charter in Philadelphia, Prospects in Canton, and Erie. He used the words that activated a network across state lines. “Red alert. No foul.”

In the world of outlaw motorcycle clubs, codes matter. They might argue over territory and business. They might fight among themselves. They might go to war. “But there is one immutable rule. You never hurt a child.” “Anyone who breaks that is a pariah, an outcast.”

The word spread fast. “Men who would fearlessly take on entire charters out of pride or profit, turned to jelly at the thought of what happens to child abusers when the club finds out.” Reaper’s calls were short, the answers instant. Engines started from Cleveland to Harrisburg. The “Old Ladies” rolled their eyes and packed sandwiches.

The Thunder Road Charter assembled at an abandoned warehouse outside Harrisburg, filling their saddlebags with first aid kits, blankets, and extra fuel. They called their wives and said “they’d be home late.” They kissed their kids and said “they had club business.” Two hours later, Reaper was still at the gas station with Violette.

They sat on the metal guardrail, his vest draped over her shoulders. They talked about her father and about motorcycles. He learned “she could identify engines by sound.” She learned “he’d been riding longer than she’d been alive.” He learned “she liked root beer and no cartoons.” She learned “a club name came from their reputation for ending fights quickly.”

When she asked why he had called Smoke, he told her about the code. “He told her that some men believed in something bigger than themselves.” “He told her she had done nothing wrong.” For the first time since Daniel’s death, Violette felt that “someone other than her father saw her, the growl.” The rumble that reached Millbrook that evening made the windows rattle.

Three people stepped onto their porches. The first wave wore the Thunder Road rocker. “They were men in jeans and boots, some with gray beards, some with tattoos up to their necks.” “They were electricians, carpenters, mechanics, truck drivers, veterans.” They were also convicted felons, brawlers, and corner-runners.

They stood shoulder to shoulder, leather jackets creaking, watching Corbit’s house. The second wave wore the Steel City rocker, their patches stitched onto black leather that smelled of machine oil and cigarettes. The third wave was Lake Erie, the brothers who rode through snowstorms “because they hadn’t missed a red alert in 20 years.”

Then came the independents, Pagans, Bandidos, even a few Ghost Riders. In any other context, these clubs would not ride together, they would clash. “But today they were united by a single purpose, their collective presence looked like something out of a post-apocalyptic movie.” Sheriff Pete Pierce arrived to the sight of two hundred bikes lining his street.

He was a stocky man with a gut earned from too many diner breakfasts and too few gym visits. He had been a deputy for a decade before running for Sheriff. He believed in procedure, in paperwork, in proper channels. He had never angrily drawn his weapon.

He had always believed that his town’s worst problems were teenagers drag racing and couples arguing too loudly. The sight before him made his stomach sink. For a split second, he imagined calling the SWAT unit from Harrisburg. Then he saw the little girl standing in the glow of the gas station sign, his Cut draped over her, and he felt the shame rise in his cheeks.

He remembered the social services visits, the nervous eyes, the bruises hidden beneath long sleeves. He had believed Randall “because Randall looked like him.” He had dismissed the signs “because he didn’t want to rock the boat.” Now the boat was being rocked by an army of motorcycles.

“We need to talk,” he said to Smoke, feeling the weight of every law book he had ever read. “You can’t just roll into town and do whatever that is.” Smoke was taller than Peace, his beard neatly trimmed, his eyes the color of thunder clouds. He listened, then spoke quietly enough that only the front row could hear him, but his voice carried like gravel.

“There’s a little girl with a scar on her face. Fresh. You were at that house. You knocked on that door. You left. We are not here to break laws, Sheriff. We are here to ensure the law does its job.” Peace was irritated. He wanted to say “he did his best.” He wanted to say, “there were procedures.”

Instead he said, “You have one hour. After that, I’m calling everyone.” Smoke nodded. “That’s all we need,” he said. It was a lie. They had as long as they wanted. But politeness bought a lot. Inside the Corbit house, Randall sat in his TV chair, watching college football, half a six-pack deep into the afternoon. He heard the growl like distant thunder.

He muted the TV. The growl got louder. Randall paced like a caged animal. Through the window, he saw the line of chrome and leather. He saw his neighbors peeking through the blinds. He saw Sheriff Pierce talking to a biker. He thought about running, slipping out the back door into the woods. But there were men there too, leaning against their handlebars, arms crossed.

He thought about calling a lawyer. He thought about the scar on Violette’s face. He thought about locking her in her room for hours because she spilled his drink. He thought about throwing her shoes into the fire because she left them by the couch.

He thought about the times he had pressed his hand over her mouth and threatened her. And for the first time, he felt what Violette had felt for three years. Fear. Mother stood at the bottom of the stairs, gripping the dish towel, her legs trembling, her heart pounding. She looked at the man she had married, the man who had promised to protect her, the man who had called her stupid and lazy and worthless, the man who had thrown a bottle at her child. She felt anger like fire.

She hadn’t felt anger in so long. She had swallowed it to keep the peace. “It felt good.” “They won’t leave,” she said. Randall pointed the gun at the floor, his chest rising and falling. “If you open that door, you’ll regret it,” he said. “We’ll both regret it.” “We already do,” she said, and turned the knob.

The air outside was cold. The noise hit her like a wave. Engines idled like a single organism. Headlights lit up the porch. The Old Ladies stood in the yard, waiting. Smoke stood at the bottom of the steps, hands at his sides, palms visible. “Your daughter is safe,” he said.

“She’s with my wife and some of the other women. She’s eating and laughing. She’s fine.” Mother broke down crying. They were loud, uncontrolled sobs. She had forgotten what it felt like to cry freely. “I should have protected her,” she said between breaths.

“I didn’t know how. I was so scared. I was so stupid.” Smoke shook his head. “You’re protecting her now. That’s what matters.” She nodded. He asked her to tell them everything. She did. Her voice firmed as she recounted every bruise, every apology, every broken promise. The bikers listened.

They weren’t shocked. They had seen it before. Some of them had lived it. They felt the familiar burn in their bellies that came when a line was crossed. Inside, Randall heard his wife telling strangers his secrets. He felt the world shrinking.

He heard the word “monster” whispered. He heard, “She’s my daughter. Daniel’s daughter.” he punched the wall. He sat on the couch. He thought about putting the barrel of his gun in his mouth. He weighed it. He thought about coming out shooting. He thought about staying inside. Every option seemed worse than the last. He decided to wait.

Maybe the bikers would get bored. Maybe they would leave. He opened another beer. The label trembled between his fingers. Outside, the minutes dragged on. The engines idled. Breath plumed in the cold air. Sheriff Peace called Child Services. He radioed for backup, out of habit, but no one came.

Millbrook had a part-time deputy on the weekend, and he was home looking after his own kids. Peace felt useless. He sat in his patrol car, staring at the dashboard. “He was the law, and yet he had failed.” “When a system fails, something fills the vacuum.”

That night, it was leather and chrome. Reaper knocked on the garage door. He knocked politely. “Come out,” he said. “We aren’t leaving quietly.” He knocked again. “Come on, Randall, let’s talk.” Randall sat there, gun in hand, staring at the door. He could see the shadow of boots beneath the gap. He could hear the voice. He swallowed. He stood up.

He tucked the gun into the waistband of his jeans, hidden by his shirt. He opened the door a crack. Cold air rushed in. Leather, beards, and patches filled his vision. He felt small. He stepped onto the porch, the gun concealed. Smoke was closer now. Randall tried to muster anger.

“This is illegal,” he said. His voice broke. “You can’t just threaten me.” “We are not threatening you,” said Smoke. “We are having a conversation.” He glanced at Randall’s waistband, saw the outline of the gun. He nodded to Reaper. Reaper shook his head. Not yet. Smoke stepped forward. “Child Protective Services is on their way. You will go with them. You will tell them everything.”

“You will sign whatever papers they put in front of you. You will stay away from this house and these women. And you will understand that if you ever hurt a child again, we will know. We will swarm you like flies on garbage.” Randall sneered, “Or what?” Smoke stepped closer. Randall had to look slightly up.

Randall was bigger, but size does not mean presence. “I was in Vietnam,” Smoke said quietly. “I held my friends while they bled out in rice paddies. I carried brothers to graves. I took bullets. You think you scare me. You’re a drunk with a gun. Put it away!” Something in his tone broke Randall’s swagger.

He flinched, then in front of the whole town, pulled the revolver from his waistband and placed it on the porch railing. Smoke nodded. Sheriff Peace exhaled the breath he had been holding. Within minutes, Child Services arrived. A social worker with tired eyes got out of the back of a patrol car.

She had been at the hospital on the night of the bottle. She recognized the girl, she recognized the mother. She walked up the steps and stood beside Smoke. “Mr. Corbette,” she said, “You’re coming with us.” Randall looked at the sea of faces. He looked at his neighbors filming with their phones.

He looked at his wife, who stood tall, no longer timid. He didn’t fight. He held out his hands. Deputies cuffed him and led him away. The bikers didn’t cheer, they didn’t clap, they simply watched him go. Then, one by one, they shut off their engines and reached into their saddlebags. They handed Mother blankets, canned goods, paper towels, cash.

They wrote down phone numbers. They kissed Violette’s forehead. They told her “she had done nothing wrong.” Smoke gave her his card. “Call anytime,” he said. Reaper ruffled her hair. “You have family now,” he said, “not just blood, family by choice.” The next months were not easy. Randall’s trial took time.

He initially pleaded not guilty, claiming “the bikers had coerced him.” The defense tried to portray Reaper and Smoke as vigilantes. The prosecutor introduced the hospital records, the teacher’s notes, the social services visits. Mother testified, telling the truth. Violette testified, and with a voice that trembled but never broke, she told the jury about bottles and boots and nights locked in her room.

Randall looked at the floor. The jury found him guilty in less than two hours. The judge, who had grown up in Millbrook, sentenced him to five years. He would serve three if he behaved. In prison, the word gets around why you are there faster than a shiv. Randall learned what “pariah, an outcast” meant.

Mother and Violette went through therapy as if wading through mud. Progress was slow. There were nightmares. There were triggers. Violette flinched at the sound of beer bottles opening. She hated football on TV. She loved the smell of grease. The garage became a workshop again.

Mother painted the walls a cheerful blue. Violette hung up her father’s photo. She wrote “Brenner Garage” on a piece of scrap wood and nailed it above the door. She invited Reaper and Smoke to a barbecue that summer. They came, they brought their wives and children. They ate hot dogs off paper plates.

The neighbors peeked through the curtains, but fear had now turned to curiosity and respect. One evening, a week after Randall went to prison, Reaper knocked on the garage door. He held a small jacket. It was soft but tough leather, with a patch on the back that read “Honorary Little Sister Thunder Road Charter.” Beneath it, stitched in script, was “Violette the Mechanic!” Violette’s eyes went wide.

“What is it?” she asked. “It’s for you,” said Reaper. “It means you’re one of us. It means we come if you need us.” “No questions.” She put it on. It was a little too big. She didn’t care. She felt protected. A month later, Smoke showed up with a trailer.

Inside was a red 1971 Honda Trail 70. It was missing a few parts. “Found her at a flea market,” he said. “Thought you could use a project.” Violette spent the evenings rebuilding it, looking up manuals, calling Reaper when she got stuck.

She learned to set spark plug gaps, adjust float height, and tune the throttle cable. She even painted the little bike to match her father’s old toolbox. When she finished, Reaper installed removable training wheels. Violette wore her jacket and helmet and rode in circles in the yard. Her laughter healed through the neighborhood. Mother watched from the porch window. Tears in her eyes.

Reaper took a photo with his phone and sent it to Smoke with the caption. “She flies” Spring came. The trees budded. The town forgot in its own way. People talked about the high school football team again, about gas prices, about the new pastor at the Methodist church.

But the sound of motorcycles still made eyes drift to the windows. The paint patch over the mailbox that read Corbet peeled off completely. Violette sanded it down and painted “Brenner” in bold black letters on it. When the mailman saw it, he tipped his hat years later.

When Violette was in her teens, she would get her motorcycle mechanic certification. She would open her own repair shop in Harrisburg. She would marry a man who respected her. She would one day open her own shop and tell her children about the day 250 bikers came to Millbrook.

She would tell them “that justice is not always served in courtrooms and heroes don’t always wear uniforms.” “Sometimes they wear leather, sometimes they ride Harleys, sometimes they are named Smoke and Reaper.” “And sometimes the bravest person in the story is a little girl who speaks the truth and a mother who finally listens, if this story has one message, it’s not that vigilantism should replace the law.”

“It doesn’t say that everyone should form a posse.” “It says there are rules that go beyond statutes.” “One is that children deserve protection.” “Another is that people in positions of power, law enforcement, teachers, neighbors need to look closer when something is wrong.”

The nurse who stitched Violette’s face could see the truth but had no authority. The Sheriff had authority but chose convenience. “It took outlaws to make everyone else uncomfortable enough to act.” “Sometimes you have to be willing to be uncomfortable to do the right thing.”

“Sometimes angels wear leather, sometimes heroes ride motorcycles, and sometimes, when a child whispers, he’s going to hurt my mom, the right answer is: ‘Get his name and then do something about it.’” “Believe children, protect the innocent. Never let fear keep you silent when someone needs help.” “Because somewhere, right now, another Violette is tracing diagrams in a library, waiting for someone to notice the scar on her face and ask the question that will change everything.”

News

“LOCKED IN THE MUDROOM: 11-Year-Old Escapes Guardian, Cuts Chains to Free a Man, and Triggers a 1,000-Biker ESCORT to the Courthouse. The Town’s Secrets Could No Longer Hide.”

“LOCKED IN THE MUDROOM: 11-Year-Old Escapes Guardian, Cuts Chains to Free a Man, and Triggers a 1,000-Biker ESCORT to the…

“OUTLAW BIKER STITCH PAID $15,000 to BUY a Child from Traffickers at 3 A.M. What the Hell’s Angels Did NEXT To The Foster System Will Shock You.”

“OUTLAW BIKER STITCH PAID $15,000 to BUY a Child from Traffickers at 3 A.M. What the Hell’s Angels Did NEXT…

“SILENCE SHATTERED: Biker Boss’s ‘Deaf’ Son Was TRAPPED for 7 Years Until a Homeless Teen Risked Everything. The Unseen Object She Extracted Changes EVERYTHING!”

“SILENCE SHATTERED: Biker Boss’s ‘Deaf’ Son Was TRAPPED for 7 Years Until a Homeless Teen Risked Everything. The Unseen Object…

“CHRISTMAS MIRACLE: 7-Year-Old Takes Bat for Biker, and 500 Patched OUTLAWS Roll Up to Demand JUSTICE. The TOWN HUSHED When the Angels Arrived.”

“CHRISTMAS MIRACLE: 7-Year-Old Takes Bat for Biker, and 500 Patched OUTLAWS Roll Up to Demand JUSTICE. The TOWN HUSHED When…

“FATEFUL CHRISTMAS EVE: Desperate Mother Begs for Hot Water… And 200 HELL’S ANGELS Answer the Call. The Unbelievable Retribution the Entire Town Didn’t See Coming!”

“FATEFUL CHRISTMAS EVE: Desperate Mother Begs for Hot Water… And 200 HELL’S ANGELS Answer the Call. The Unbelievable Retribution the…

The Craziest Act of the Blizzard: She Risked Opening Her Door to an Outlaw Gang, But What They Brought Was Even More Terrifying!

The Craziest Act of the Blizzard: She Risked Opening Her Door to an Outlaw Gang, But What They Brought Was…

End of content

No more pages to load