“LOCKED IN THE MUDROOM: 11-Year-Old Escapes Guardian, Cuts Chains to Free a Man, and Triggers a 1,000-Biker ESCORT to the Courthouse. The Town’s Secrets Could No Longer Hide.”

“Please don’t let him take me back.” Those six words whispered by an 11-year-old boy into the warm air of a roadside cafe would trigger the largest child protection escort Pine County had seen in a decade. Noah Parker didn’t come in asking for food or sympathy.

He came in holding a cracked orange voice recorder claiming he’d cut a chain in the woods to free a grown man. And the same respected guardian who led prayers on Sunday was now counting down the days until harvest days so he could make the boy disappear quietly. For 278 days, Noah had been trained to stay small, stay silent, stay out of the way.

But what happened 12 minutes after he said those words would flip the whole town on its back. This is Noah and Anker’s story, and it doesn’t end the way you think. “Before we continue, please subscribe to the channel and let us know where you’re watching from in the comments. Enjoy the story.”

“The recording is in my pocket,” Noah whispered like he was reminding himself not to drop it. He stood just inside Ruthiey’s Timberline Cafe on County Trunk H, where the neon mug in the window buzzed and the coffee pot gurgled like it was fighting sleep. It was 5:58 a.m. Fog pressed against the glass. The air smelled like burnt bacon grease and pine damp jackets drying near a heater vent.

Noah looked like a kid who’d been trying very hard not to be noticed. 11 years old, small, narrow shoulders, sandy blonde hair cut too fast with dull clippers, pale gray blue eyes with dark circles underneath, the kind you get from too many nights listening for footsteps.

He wore a faded forest green jacket with a shoelace tied where the zipper pull used to be. His jeans were clean but worn thin at the knees. His left sneaker had clear packing tape wrapped around the toe like a bandage. And when he walked, the sound gave him away. Tap tap. Because his left ankle wasn’t healed and he couldn’t hide the limp, he hugged a small backpack to his chest with both arms.

His thumb rubbed the corner of a laminated school photo until the edge went cloudy. When Noah panicked, his words ran together. When adults raised their voice, even a little, he flinched. And this morning, he had 10 minutes before the truck came. 10 minutes before Caleb Vaughn left the gray house on Birch Run Road and realized Noah wasn’t in the mudroom. 10 minutes before the passenger door opened and Noah got yanked back into a life that smelled like mildew, detergent, and locked doors.

Noah scanned the cafe like he was searching for the safest face in the room. 16 patrons, early shift workers in reflective vests, a tired woman with a laptop, an older couple sharing pancakes, heads down, nobody looking for trouble. And in a corner booth facing the door, three big men in black leather vests sat quiet as stones. Hell’s angels. Noah’s stomach turned.

Not because he thought they’d hurt him, because he knew what adults did when they saw a patch. They used it as an excuse to stop being responsible. Still, Noah moved toward the first table that looked harmless. Rejection one came from a middle-aged couple in matching fleece jackets. When Noah stepped close and said, “Excuse me, can I use your phone? I need help,”

They didn’t answer. They slid their plates away and scooted deeper into their booth like the boy was a spill. Noah nodded like it was normal, like it didn’t stab him, then backed away. He tried the counter next. The cashier had reading glasses low on her nose and a sign taped to the register.

“No loitering, no exceptions,” Noah asked anyway, voice thin. “Ma’am, please. 1 minute.” Her eyes flicked to his taped shoe, then to the leather vests in the corner, then back to Noah, calculating risk. “We don’t have a public phone,” she said, even though the landline sat behind her. “If you’re waiting on someone, you can wait outside.” Rejection, too, wasn’t angry.

It was worse. It was administrative, like he was a problem to be removed. Noah’s thumb rubbed the photo edge faster. He tried a man sitting alone in a county maintenance jacket, keys on the table. “Sir,” Noah said, “did you hear about somebody on the logging trail behind Harrow Lake.”

The man let out a short laugh like Noah had told a joke he’d heard too many times. “Kid, the woods got more stories than trees. Go home.” Rejection three made two other tables glance over then look away fast. Noah’s throat tightened. His eyes darted to the windows and the door. He started counting under his breath. 1 2 3. Because counting made fear smaller. Then he saw them.

Three women in pressed blouses at a booth near the middle, dressed like it was Sunday, even though it was Thursday. One wore a silver cross necklace that caught the light when she turned. Noah recognized them from Pine Hollow Community Church.

The kind of people who talked about doing right while letting wrong happen as long as it stayed quiet. This had to work. Noah told himself it had to. He stepped up, voice shaking. “Mrs. Harlland, please. I’m not lying. He’s going to make me go back.” “Who is he?” One of them asked, already annoyed. Noah swallowed. “Caleb vaugh. He locks me in the mudroom. He took my” The woman’s mouth tightened.

Another leaned forward, hands folded. “In this town, we don’t accuse people because we’re upset.” “I’m not upset,” Noah said. “I’m scared.” The third shook her head gently, the way gentle can be cruel. “God doesn’t work through motorcycle gangs, honey, and he doesn’t work through lies.”

“You should stop repeating stories you don’t understand.” Rejection 4 wasn’t just a no. It was moral cover. Noah backed away, shoulders curling inward, trying to take up as little space as possible. His eyes burned. He blinked hard, but a tear still slid down and caught in the yellowing bruise on his cheekbone. That was when a chair scraped.

Not loud, not dramatic, just enough to change the air. From the corner booth, one of the hell’s angels stood. He was tall and broad, gray threaded through his beard, scar across his knuckles, calm gray eyes that didn’t hunt for weakness, just noticed it. He walked over like a wall being placed gently in front of a child.

He stopped two steps away and lowered himself until he was eye level with Noah. Noah’s taped sneaker made that same soft tap against the floor as he tried to stand still. “You’re shaking,” the man said softly. “That’s not confused. That’s scared.” Noah couldn’t speak. His throat was locked.

The man held out an open hand, palm up, not a grab. An invitation. “My road name is Anchor,” he said. “You tell me the truth. Slow.” Noah stared at the open palm like it was a rope tossed into a river. Then the words fell out, broken and honest. “Please don’t let him take me back.” Anchor’s face didn’t change much, but his jaw tightened like a latch clicking into place. “Okay,” Anchor said.

“10 seconds, just 10.” He counted in a low voice. “One, breathe in. Two, breathe out. Three, look at me, not the room.” By 10, Noah’s shoulders had dropped an inch. Not safe, not yet, but seen. Anchor guided him to the corner booth, inside seat, and sat on the aisle side like a quiet shield. The other two riders made space without questions. A mug of hot chocolate appeared. A plate of toast slid closer.

Noah didn’t touch it. Hunger made him cautious. Anchor didn’t push. “One bite,” he said. “Then another.” Noah took a bite. Warm, simple, like a memory. Anchor kept his voice low. “Name?” “Noah,” he whispered. “Noah Parker.” “Age?” “11.” “Where do you live, Noah?” “The Grey House on Birch Run Road near the culvert.” Anchor nodded once.

“How long until Caleb Vaughn notices you’re gone?” Noah’s face went pale. “5 minutes,” he whispered. “Maybe less.” Anchor’s eyes flicked to the door, then back. “Okay, tell me what happened that made you run.” Noah swallowed. He reached into his backpack and pulled out the cracked orange voice recorder. He held it with both hands like it could save him if he didn’t drop it.

“I cut a chain,” Noah said, voice shaking. Anchor didn’t blink. “Where?” “Behind Harrow Lake,” Noah whispered. “On the old logging trail.” Noah’s fingers tightened around the recorder. “I heard metal dragging. I followed it. There was a man on the ground, chained to a tree. His hands were tied. He had a vest like yours, but muddy. His lips were blue.” Anchor waited still as a post.

“I had a little multi-tool,” Noah said, “from my dad’s tackle box. I saw at it until it snapped. It took forever. My hands hurt, but I did it.” An 11-year-old alone in fog and pines, cutting a chain meant for an adult. Noah said it like he was confessing a crime, not describing courage. “And when it broke,” Noah whispered. “I fell back, twisted my ankle.”

“That’s why I” He nodded toward his taped shoe. “That’s when I ran for help.” Anchor’s gaze lowered to the limp, then back to Noah. “The man, did he say anything?” Noah’s voice dropped. “He said my name like he already knew it.” Anchor’s eyes sharpened. “He said, ‘Your name.’” Noah nodded, terrified of what that meant. “Then I heard a truck.” “The man shoved me behind a log. I stayed quiet.”

“5 seconds, maybe more.” Noah looked toward the window again. “Caleb’s truck rolled up on the trail.” The air in the booth tightened. Noah pushed through. “Caleb got out. He wasn’t surprised. He said, ‘You made me walk for it.’” “The biker said, ‘Don’t do this, Van.’ Like, like they knew each other.” Noah’s breath shook. “I ran home. Caleb got there later.”

“He locked me in the mudroom and told me the woods was a test.” “He said, ‘If I talked, nobody would believe me over a good man.’” Noah’s eyes flicked toward the church women. “He was right.” Anchor leaned in. “Has he kept food from you?” Noah nodded. “Locked doors from the outside.” Noah nodded again. “Stopped you from seeing a doctor alone?” Noah’s voice cracked.

“Yes.” Anchor didn’t explode. He didn’t vow revenge. He did the more terrifying thing. He got calm. “Has anyone tried to help you before?” Anchor asked. Noah swallowed and the staircase began. “I told my teacher,” Noah said. “She called home.” “Caleb showed up smiling with donuts.” “That night, I paid for it.” Noah’s fingers rubbed the photo edge again harder. “I went to the school counselor.”

“Caleb waited in the hallway.” “The counselor talked to him.” Noah’s voice got thin. “I went to the sheriff desk.” “The deputy told me to handle family stuff at home.” “He called Caleb.” “Caleb came and thanked him.” Noah looked up, eyes wet. “So, I don’t know what to do anymore.” Anchor held his gaze. “You did it,” he said.

“You came here.” Noah shook his head. “They turned me away.” Anchor’s voice stayed steady. “I’m not.” Noah blinked fast. “He’ll come here. He’ll take me.” Anchor asked permission like it mattered. “Can I touch your shoulder?” Noah nodded. Anchor placed two fingers lightly on Noah’s shoulder. “If Caleb walks in,” Anchor said, “you look at me. Not him. Not anyone else. Me.”

“If you believe kids deserve one adult who doesn’t look away, comment, ‘Stand with Noah,’ and subscribe because what happens next will prove this town’s silence was never stronger than the truth.” Then Anchor stood, took two steps away, and made one call that would wake up three chapters before dawn. “President, sundown,” Anchor said into the phone, voice calm. “It’s Anchor.”

“I need every brother within 80 miles at Ruthy’s Timberline Cafe.” “Now the line stayed quiet for a beat, heavy with meaning.” “What’s going on?” Sundown asked. “An 11-year-old walked in with proof his guardians been locking him up and planning an accident before harvest days.” “We’re not waiting for the system to take its time on this one.”

“Say no more,” Sundown said. “We’re coming.” The line went dead. And that was it. No debate, no questions about legal complications, just movement, because that’s what brotherhood meant. Anchor returned to the booth. Noah stared at him like he’d just dialed lightning. Anchor nodded toward the recorder. “What’s on it?” Noah swallowed.

“Three nights ago, Caleb was on speakerphone. He didn’t know I was awake.” Noah’s hands shook. “He said the kid’s account. He said he wasn’t losing it. He said a number like it was a prize.” Anchor’s eyes didn’t leave Noah’s face. “The number.” Noah’s voice dropped to a whisper. “1729.” “And he said,” Noah continued, “Before harvest days, he said it had to be quiet.” “He said nobody asks questions if he’s the one leading the prayer.”

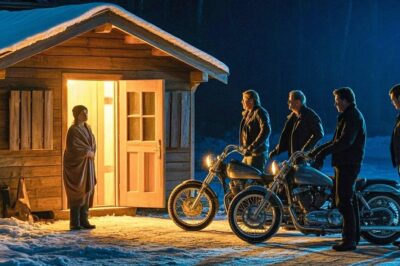

Anchor’s jaw tightened. “Okay.” Noah blinked. “Okay.” Anchor nodded. “Okay means we move smart. We move clean. We make it impossible for him to rewrite the story.” Outside a low rumble drifted through the fog. At first it sounded like distant thunder. Then it grew. Not chaotic, not angry, organized.

Two headlights appeared, then four, then a line. Motorcycles rolling in pairs, slow and controlled, parking in disciplined rows along the far edge of the lot. Engines clicking off one by one until the sudden silence felt heavy. The cafe patrons froze. Forks paused midair, coffee forgotten. “Now you might be thinking, ‘Here comes a mob.’” But watch what actually happened.

Three men walked in with the bell above the door, jingling like nothing special. First came Marshall, mid-50s, close-cropped hair, eyes that missed nothing. Former law enforcement, the kind who knew exactly which forms mattered and which excuses didn’t. Behind him came Mender, broad-shouldered with a quiet face, carrying a small medical bag, then signal, younger, lean, hoodie under his vest, already pulling a cable from his pocket.

They didn’t loom over Noah. Marshall crouched, eye level, open palm. “Morning,” he said. “I’m Marshall. I’m here to keep adults honest.” Noah’s breath hitched. Mender spoke gently. “May I look at your ankle?” Noah nodded. “Professional sprain,” he said. “Untreed. We’ll get you seen today.” “And your wrist?” Noah pulled his cuff back.

Faint finger-shaped marks circled his right wrist. Angry red where they’d been rubbed raw. Mender didn’t dramatize it. He just nodded once like noted. Signal leaned toward the recorder. “We’ll copy it,” he said. “More than once.” Noah hesitated, then handed it over like he was giving up his last shield. Anchor leaned in.

“We’re not erasing you,” he whispered. “We’re backing you up.” Marshall asked, “Is your mom safe?” Noah’s eyes flicked down. “He controls her,” he whispered. “He says he’ll take me away if she talks.” Marshall’s face hardened. Not at Noah, at the shape of Vaughn’s smile. “Okay,” Marshall said. “Then we protect both of you.”

Coach arrived next, sliding into the booth with the gentle patience of a former teacher who’d learned the language of frozen kids. “You don’t have to be brave all day,” he told Noah softly. “Just 60 seconds at a time.” Noah blinked and for the first time he didn’t feel stupid for being scared. Anchor’s phone buzzed with updates. “On our way, 10 out, two chapters behind, holding pattern.” Noah stared at the screen.

“How many?” Anchor didn’t inflate it. He didn’t perform. “Enough,” he said. “And then more.” Marshall stood and began the part most people don’t think about when they imagine rescue paperwork. He called the county child advocacy hotline. He called the non-emergency sheriff line. He used words like imminent risk, recorded evidence, and emergency protective custody because villains like Caleb Vaughn survived on vagueness and delay.

Meanwhile, Vellum, elder statesman, the one who wrote things down so nobody could pretend later, moved through the cafe and found the person guilt had finally loosened. “Irene Caldwell, 70 years old, lives two doors down from the Vaughn house, hands shaking around a coffee cup like it was the only steady thing left in her life.” “She didn’t want to look at Noah.” “Shame wouldn’t let her, but she talked.”

“I heard the latch,” Irene whispered to Marshall, voice breaking on latch. “Wednesdays, usually Wednesdays around 9, and sometimes Sunday afternoons after church, she swallowed hard. I told myself it was grounding. I told myself kids cry. Then I heard him crying quiet like he knew loud would make it worse.”

Irene’s eyes filled. “I called once.” “A deputy came when Caleb was at work. Knocked. Nobody answered. Left. After that, I convinced myself someone smarter would handle it.” Marshall took it down. Dates, times, what she heard, what she saw. Because guilt becomes useful when it becomes evidence. Signal returned the recorder to Noah.

“Three copies,” he said. “One in my pocket, one in anchors, one encrypted. Nobody’s losing this.” Noah held it again, but it felt different now. Less like a secret, more like a key. Anchor leaned close. “We’re moving you out before Vaughn shows up,” he said. “Not for confrontation, for safety.” Noah whispered.

“Where?” Marshall answered. Precise. “clinic first without your guardian in the room, then the child advocacy center, then an emergency custody order so you’re not sent back because somebody smiles at a deputy.” Noah’s eyes widened. “They can do that.” “They can,” Marshall said. “And they will.” Outside, the rumble returned bigger now.

More headlights, more bikes, more disciplined rows filling the foggy lot. Chrome glinting under yellow parking lights. Noah stared, heart pounding. “Harvest days is in nine days,” he whispered. Anchor nodded. “Which means Vaughn thinks he has nine days to make you vanish into a story everyone will repeat for him.” Anchor’s calm voice carried steel now.

“We’re taking that time away.” Noah’s eyes darted to the window because somewhere in that fog, a truck was moving. Caleb Vaughn was waking up to a world where the boy he’d tried to lock away had finally been believed quietly, legally, and at a scale too big to ignore. And Noah didn’t know it yet. But the next step wasn’t a brawl.

It was a door opening. The kind that comes with a judge on a phone call, a clinic nurse closing the exam room door, and a line of calm men outside making sure nobody talks their way out of the truth. Because now, armed with a recording, a witness, and brothers who understood both fear and procedure, Anchor was about to lead the first move of a plan that would drag Pine Hollow’s secrets into the daylight. At 6:23 a.m.

, President Sundown walked into Ruthie’s Timberline Cafe like he’d been there a hundred times, even though he hadn’t. 61. Weathered face, silver hair clipped short. A voice so calm it made other people lower theirs without realizing. He took one look at Noah Parker’s taped sneaker, the yellowing bruise on his cheek, the red ring marks on his wrist, and the way the kid hugged his backpack like it could stop a hand from reaching for him.

Then Sundown sat down across from Noah and spoke so softly. The nearest booth had to lean in to hear. “Morning, son,” he said. “You did the hardest part. You told the truth.” Noah swallowed. “He’s going to say, ‘I’m lying.’” Sundown nodded once. “Men like that always do. We don’t argue with their story. We prove ours.”

Sundown looked around the booth at Anchor, Marshall, Mender, Signal, Coach, and Vellum. “And that’s when the room went still in a way that wasn’t fear.” “It was focus.” “All in favor of doing this clean, Sundown asked. Paperwork first, protection first, truth first.” For a moment, nothing.

Just the neon mug buzzing in the window and the coffee pot gurgling behind the counter. Then hands rose. Anchor, Marshall, Mender, Signal, Coach, Vellum. Every single one. No hesitation, no debate. Sundown lowered his chin. “Then we move.” Marshall stepped into the fog outside and got the on call judge on the line. “Ex parte emergency protective custody.”

“He said 11-year-old male reports false imprisonment, neglect, and threats tied to harvest days. We have physical indicators consistent with restraint and recorded audio indicating imminent harm.” The judge’s voice was tired but sharp. “Where is the child inside with EMS and a county social worker?” Marshall said any reason return is immediately dangerous.

Marshall glanced through the glass at Noah’s flinch every time the door chimed. “Yes,” he said. “Immediate and escalating.” At 6:38 a.m., the judge issued a 72-hour emergency custody order pending a hearing. Marshall printed it at the counter and set it on the table like it weighed 10 lb. Noah stared at the paper. “So, I don’t have to go back.” Coach leaned in. “Not today,” he said.

“Not because you’re lucky. Because the law finally sees you.” The first mission countdown wasn’t about drama. It was about safety. “16 minutes to Pine Hollow Clinic.” Anchor said. “Fog’s thick. We go steady.” Outside, the lot had become a quiet grid of motorcycles parked in disciplined rows. Engines cut off in waves until the silence felt heavy.

“Now, you might be thinking, this is where it turns into chaos.” But watch what actually happened. The convoy rolled out like a practiced drill. bikes first, spacing tight and smooth, then EMS, then the social worker and Marshall. No revving, no yelling, just purpose.

At the clinic, the receptionist’s eyes jumped to the leather vests and stiffened. Anchor didn’t push forward. He stepped back, palms open, and spoke like a man who understood that calm is how you keep the story clean. “We’re here for an 11-year-old with a custody order,” he said. “We’re not the headline. He is.” Marshall slid the paperwork across the counter.

The administrator appeared from the hallway in under 30 seconds. Noah got X-rays, a badly aggravated sprain. His wrist showed inflammation where something tight had dug in. His weight was low enough that the physician used the phrase “failure to thrive” and wrote it down. And for the first time in months, Noah answered questions without anyone looming 2 feet away, smiling like a warning.

In the waiting room, Signal cleaned the orange recorder audio just enough to make the important words undeniable. Caleb Vaughn’s voice came through scratchy but clear. “1729. before harvest days. No loose ends.” That number wasn’t a code. It was money. Marshall pulled public probate records on Noah’s father before lunch. “Restricted trust 10072,900 principal. Monthly survivor benefits $1,92.”

Then he subpoenaed what he could fast through the DA’s office and got a partial picture of where the money went. “A used snowmobile, casino cash outs, a truck lift kit, dozens of withdrawals, thousands of dollars, zero spent on Noah.” At 2:08 p.m., Marshall finally got the sheriff on the phone.

Sheriff Dan Rusk sounded polite, overworked, almost bored. “Sounds like a family dispute,” Rusk said. “If the child’s safe, we’ll circle back.” Marshall kept his voice neutral. “Sheriff, we have a judge signed emergency custody order and recorded evidence of planned harm tied to a public event.” There was a pause.

Then Rusk said the sentence that explained 8 months of failure. “Caleb’s a harvest day’s contractor,” he said. “He’s got people vouching for him.” Conflict, protection, convenience. That was the final rung of the ladder, not just a slow system, a tilted one. Marshall bypassed the tilt. By 4:41 p.m.

, Assistant DA Marin Hol filed for a search warrant using the custody order, the medical findings, Noah’s statement, and the recorder transcript. At 6:02 p.m., a judge signed it. At 6:33 p.m., a small convoy rolled toward Birch Run Road. Two deputies from a neighboring county to avoid local entanglements. The social worker, the child advocate, and Marshall.

Across the street, Hell’s Angel’s bikes staged in quiet rows like centuries. Present, non-interfering, visible enough that nobody got brave with a lie. The gray house looked ordinary. Vinyl siding, a bird feeder, a welcome mat. But beneath that welcome was a mudroom door with a lock on the outside.

When the deputies knocked, Caleb Vaughn opened the door wearing a pancake stained t-shirt, humming like a man interrupted during a normal night. Because to him, this was normal. He smiled when he saw badges. “Evening folks, can I help you?” The warrant was read. The entry was calm. The search was methodical. The mudroom hit first.

Stale detergent, damp drywall, mildew that clung to the throat, a thin mattress on the floor, no real window, a vent that rattled when the furnace kicked on. Then the utility closet. A metal document box exactly where Noah said. Combination lock. The code was taped under a shelf. Inside were bank statements, ATM slips, and receipts that lined up with the snowmobile and casino withdrawals.

And then Marshall found the folder that turned a single case into a pattern. It was labeled in neat black marker. Holly Holly Marie Vaughn. Date of death, February 17th, 2020. death certificate, accidental carbon monoxide exposure from a portable heater in the garage. But behind it sat an insurance policy. Coverage: $198,000. Beneficiary: Caleb Vaughn.

Policy increase date January 9th, 2020, 5 weeks before Holly died, and a payout confirmation showing the check had been cut. Marshall felt cold climb up his arms. Because now Noah wasn’t just a kid in danger. He was the next obstacle in a familiar timeline. While deputies inventoried documents, Vellum and Marshall collected the voices the town had swallowed.

First came Llaya Hartwell, 57, former church treasurer, who’d lived in Pine Hollow for 32 years and held the offering books for 12. She stood on the sidewalk with her hands twisting a tissue into a rope. “What she saw?” “Noah every Sunday. Same faded jacket. Same taped sneaker. Bruises that shifted from purple to yellow like a calendar nobody wanted to read.”

“When she saw it after men’s breakfast, she said, ‘Every second Sunday when Caleb volunteered to walk him to class.’” “Why? She stayed silent. Fear and shame dressed up as faith.” “Pastor told me not to gossip,” Laya whispered. “And Caleb told me, smiling, that people who spread lies can be sued.” “how she feels now.” Her hands shook as she spoke.

“She couldn’t meet Marshall’s eyes when she said Noah’s name.” Her confession came out raw and small. “I knew something was wrong. I just I didn’t want to be the one who tore the church apart.” Then she handed over what guilt had made her keep. copies of ledger notes about benevolence funds Vaughn insisted on delivering personally with dates and amounts that never made it to the families listed.

The second witness came from the harvest days grounds. Roy Tam, 73, retired electrician who’d wired the barn lights for 20 years and knew every camera angle like he knew his own kitchen. “Introduction Roy, a man who lived by routines, had noticed a change that didn’t fit.”

“What he saw, a revised route map, a new security sweep path, and a dark corner behind the livestock barn where cameras didn’t reach.” “When he saw it, last Tuesday, Roy said, ‘When the committee met, Caleb asked me not to add a light there. Said it would ruin ambiance.’” “why he didn’t act.” Roy’s mouth tightened. “I told myself it wasn’t my job. I told myself it was just festival nonsense.” “How he feels now.”

“His voice broke on the word boy.” He wiped his face with the back of his hand and looked past the house like he couldn’t stand seeing it. “His confession.” “I knew it was wrong. I just I didn’t want trouble in my last good years.” Roy signed a statement and attached the root map he’d kept. Evidence, not outrage. Then the final institutional failure showed itself in the driveway.

Sheriff Rusk arrived late, face tight when he saw neighboring deputies already inside and a warrant already executed. He tried to take control with that official tone small towns use like a shield. “We’ll handle it from here,” he said. Marshall didn’t argue. He simply handed him copies. Custody order, warrant, recorder transcript, medical report, insurance folder, witness statements.

Rusk’s eyes flicked to the policy increase date, then to the root map, then to the trust withdrawals. For a second, fear flashed. not of Vaughn, but of what it meant that he’d been slow walking this. Marshall’s voice stayed even. “Sheriff, you told me he had people vouching for him. Who?” Rusk’s jaw worked. “He’s on the festival committee,” he said. “He donates.”

Marshall nodded. “That’s not a reason. That’s the problem.” At 11:53 p.m., Caleb Vaughn was placed in handcuffs in his own driveway under the porch light, still smelling like syrup and dish soap. The deputy read him his rights while Vaughn kept his face calm, like calm could rewrite reality.

He was booked on felony child neglect, false imprisonment, intimidation of a victim, theft by fiduciary, and fraud tied to the trust access. And after the Holly folder hit the DA’s desk, a separate review was opened into Holly Vaughn’s death as a potential homicide, pending full file re-examination.

The next morning, bail was set at $750,000 cash or shity with a strict no contact order covering Noah, Noah’s mother, the advocacy center, and clinic staff. 10 minutes before that hearing was called, Noah sat on a hard wooden bench outside the courtroom, ankles not touching the floor, staring at the closed door like it was a mouth. Anchor didn’t tell him, “It’ll be fine.” He didn’t promise what he couldn’t control.

He just gave Noah a smaller clock. “60 seconds,” Anchor murmured. “Then another 60.” Noah’s thumb rubbed the cloudy edge of his school photo again. 1 2 3 10. His taped shoe scraped the tile once. Tap then went still. What Noah didn’t know was that the paperwork had already started moving ahead of the town’s opinions.

And once it started, it was hard to stop. When the judge said “no contact,” the courtroom went so quiet Noah could hear his own breathing. Outside, the town expected a spectacle. Instead, it got silence. The rumble started low, distant, like thunder on the highway. Then it grew into a roar that vibrated through courthouse glass.

Nearly a thousand bikes rolled in over the next hours. Three chapters plus riders who’d heard one clean sentence. “A child needs safe passage.” And the system stalled. They parked in disciplined rows across the overflow lots. Engines cut off in waves until only quiet remained. President Sundown stepped forward to the cameras, hands visible, voice gentle.

“We’re here to make sure a kid can walk into a courthouse without looking over his shoulder,” he said. “That’s it.” Noah stood between Anchor and Coach on the courthouse steps, wearing a borrowed winter jacket that actually fit. His taped sneaker was still taped, but this time when it made its soft shaft tap on the stone, nobody scooted away. People moved closer.

Justice had been served. But justice wasn’t the ending. It was only the beginning. The first night Noah Parker slept without a locked door, he still woke up three times. Not because someone touched the knob, because his body had learned to listen for it. Anyway, he lay on a real bed at Pine Hollow Family Advocacy Center, a place that smelled like clean sheets and lemon disinfectant instead of mildew and detergent.

A night nurse had left a small lamp on low. The light didn’t stab his eyes. It just existed, steady. Noah’s taped sneaker sat by the bed like a little guard dog, toe wrapped in clear tape, laces knotted tight. In the quiet, he could almost hear the sound it had made on Ruthiey’s tile. Tap like a reminder of how far he’d walked on something that should have been replaced months ago.

Anchor sat in a chair by the window with a styrofoam cup of coffee cooling in his hands. Not talking, not pushing, just staying. Coach had told Noah earlier, “Tonight isn’t about bravery. It’s about permission to rest.” Outside, Pine Hollow talked. That’s what small towns do when the truth finally shows up with paperwork attached.

Some people tried to make it about patches, but Marshall and Sundown made sure the record made it about what it always should have been, a child, a plan, and a system that stalled until it didn’t have room to stall anymore. At 9:12 a.m. the next morning, Aaron Parker walked into the advocacy center, escorted by a victim advocate and a deputy from the neighboring county.

She moved like someone stepping out of deep water. slow, unsure, eyes red-rimmed and unfocused. Noah saw her from the hallway and froze. His shoulders rounded inward like he was bracing for the old script. Aaron didn’t run to him. She didn’t overwhelm him with apologies that would make him feel responsible for her feelings.

She stopped 3 ft away, hands open at her sides, and whispered, “Hi, baby.” Noah’s thumb found the cloudy edge of that school photo again. 1 2 3. Anchor kept his voice low. “You’re in charge of your feet,” he murmured. “If you want to step forward, you do. If you don’t, you don’t.” Noah took one step, then another. Then he leaned his forehead into his mom’s sweater like he was checking whether it was real.

Aaron’s hands trembled as she wrapped him up carefully like she was afraid she’d break him. “I’m so sorry,” she said, and her voice cracked on sorry, like it had been stored in her chest for months. The advocate guided them into a private room and did the thing that actually changes lives.

She laid out the next seven days like a map. Emergency custody had already been granted. A no contact order was already filed. A hearing was already scheduled. Not soon, on paper, on a calendar, with times. Marshall brought Aaron copies and explained them without jargon. “This means he can’t call you. He can’t come near you. If he tries, it’s a new charge.”

“This means Noah can’t be returned to that house because someone feels uncomfortable with conflict.” Aaron’s eyes filled again, but this time it wasn’t only fear. It was relief so sharp it hurt. They didn’t send Aaron back to the gray house to pack. That’s how women get pulled back in. Instead, Sundown arranged a safe pickup with deputies and an advocate present. Anchor didn’t go inside.

He stayed on the porch, visible through the window, calm as a fence post. Presents without pressure. Vellum and Coach carried out what mattered. Noah’s school backpack, a small box of photos, Aaron’s medications, and a zip folder of documents Caleb Vaughn had kept locked away like trophies. birth certificate, trust paperwork, benefit letters, everything Noah said existed.

Signal photographed the mudroom lock and the outside latch, not for drama, but for court. The kind of proof that can’t be smiled away. By that afternoon, Aaron and Noah were checked into a short-term extended stay suite at North Pines’s Lodge, 214 Lake View Drive, Pine Hollow, WI54571, paid for 2 weeks upfront through the advocacy cent’s emergency fund and a club donation that never came with a speech.

Then came the longer plan, the boring plan, the plan that wins. A week later, Aaron signed a lease at Cedar Ridge Apartments. Unit 3B, 18 Cedar Ridge Court, Pine Hollow, Ji54571. First month’s rent plus deposit was $2,680. Utility startup fees were $400. A used washer from a local reseller was $220.

Sundown didn’t hand Aaron cash like charity. Vellum set it up as a transparent support fund coordinated with the advocacy center so every dollar had a receipt and every receipt could stand up in a courtroom if anyone questioned it. The trust was moved under court supervision with an independent fiduciary by day 10. Caleb Vaughn’s management authority was revoked the same morning.

Restitution paperwork started immediately. Mender got Noah into a proper ankle brace and a physical therapy schedule twice a week for 6 weeks, then re-evaluate. He also got Noah’s wrist examined by an orthopedic specialist who documented the restraint marks and inflammation as part of the medical record.

Coach helped Noah build a safe script for school. Simple sentences he could use when adults asked questions he wasn’t ready for. “I’m safe now. I’m working with the advocacy center. Please talk to my caseworker.” Because for kids like Noah, control isn’t power, it’s oxygen. 3 weeks after the arrest, the court hearing happened.

Caleb Vaughn came in wearing a button-down shirt and the same calm face that had worked on deputies for months. He tried to make it sound like discipline, like misunderstanding, like a boy acting out. But this time, the room had a different weight. The mudroom photos were entered into evidence. The medical report was entered. The trust withdrawals were entered.

The harvest days root map was entered. Laya Hartwell testified. Roy Tam testified. Irene Caldwell testified. Hands shaking, voice breaking on the word latch. And the orange recorder played, scratchy but unmistakable, with Vaughn’s own words hanging in the air where charm couldn’t reach them.

When the judge granted Aaron Parker full temporary custody and extended the no contact order, the courtroom did that strange thing courtrooms do when truth lands. It went quiet, not because people were scared, but because there was nothing left to pretend. The criminal trial followed in January. It lasted 3 days. The jury deliberated for 1 hour and 52 minutes. Vaughn was found guilty on multiple counts.

Felony child neglect, false imprisonment, intimidation of a victim, theft by fiduciary, and fraud related to the trust and benefits. The judge sentenced him to 12 years in Wisconsin state prison, structured as 8 years initial confinement and four years extended supervision with a restitution order totaling $61,870 and a permanent no contact provision.

The review into Holly Vaughn’s death was reopened as a separate investigation. The DA didn’t promise outcomes. She promised work. And for the first time, Pine Hollow understood the difference. “Now, here’s what people expected after a verdict like that.” “They expected the Hell’s Angels to celebrate loud, to act like they’d won something.” Instead, Sundown did something that confused the town even more. He asked permission.

Ruthy’s Timberline Cafe hosted a Saturday morning fundraiser breakfast. pancakes, eggs, coffee, and a silent auction run by locals, not bikers. The neon mug buzzed in the window like it always had. The smell of bacon grease clung to coats like a familiar ghost. The Hell’s Angels didn’t take the stage. They didn’t make speeches.

They flipped pancakes in the back, washed dishes, and let the advocacy center director do the talking about emergency placement programs and why family stuff is sometimes the most dangerous stuff. They raised 38,420s in one morning. Receipts posted, donations logged, a portion set aside for therapy costs not covered by insurance. A portion set aside for emergency housing for the next kid who walked into the fog. Noah didn’t stand in front of anybody.

He didn’t need to become a symbol to be worthy of help. But he did walk into Ruthie’s near the end, wearing a winter jacket that fit, ankle brace under his jeans, and those same gray sneakers still taped because habits die slow. When he stepped, the sound was softer now. Less drag, more tap. Anchor was at the counter stirring coffee like it was the simplest thing in the world.

He looked over and nodded once, a quiet, “I see you.” 6 months later, July 12th, 2026, Noah stood in the Pine Hollow Elementary gym under crepe paper streamers for the summer science fair. He had built a small model of a foggy forest trail with a tiny rescue beacon system he’d wired with a battery pack and LED lights because Signal had once shown him how electricity works when it’s used to help, not hide.

Noah’s hands still shook sometimes, especially when doors slammed in hallways. But he didn’t count under his breath as often, and when he did, he didn’t have to hide it. Aaron sat in the folding chairs with a normal mom smile that looked like it hadn’t been allowed on her face for a long time.

She’d started a part-time job at a local dental office, 24 hours a week, predictable schedule, benefits pending. Noah’s therapy sessions were every Thursday at 4:00 p.m. Trauma focused CBT plus family sessions twice a month. His physical therapy ended after 8 weeks. He kept doing the exercises anyway because as Coach told him, “Strong ankles are proof you’re planning to stay.”

And the town changed in ways towns only change when shame becomes action. Pine Hollow School District adopted a new mandatory reporting review process. Anonymous tip line, two-person verification on child welfare calls, so no single staff member could quietly drop a concern.

In the first semester, documented follow-up compliance rose to 96%. In the first year, early intervention referrals increased by 41%, which sounds scary until you realize it means adults stopped pretending they didn’t see. Harvest days still happened. The barn still smelled like hay and popcorn. The parade still rolled down Main Street.

But that camera blind spot behind the livestock barn, it got lights. Two of them bright enough to erase the idea of quiet corners. “If you’re listening to this and thinking, ‘I don’t have a thousand motorcycles.’” “Good. You’re not supposed to.” Noah didn’t need a thousand motorcycles to be worth saving. He needed one adult to stop choosing comfort. One teacher to call the right hotline and follow up.

One deputy to take a boy seriously. One church member to say, “No, actually, we’re not handling this quietly.” The Hell’s Angels didn’t replace the system. They forced it to wake up. They used calm, procedure, and presence to protect a child while the law caught up to the truth. “And the part I hope you keep is simple.”

“When a kid looks at a door more than they look at your face, something is wrong.” “When a child flinches at normal movement, something is wrong.” “When a boy shows up with taped shoes and hungry eyes and a voice that sounds like it’s trying not to take up space, something is wrong.” “Listen. Ask again.”

“Don’t let the first It’s probably nothing be the end of the story.” On the night of Noah’s 12th birthday, the advocacy center delivered a cake to Cedar Ridge Apartments. Chocolate with blue frosting. Noah blew out the candles without wishing for safety because safety had finally become normal enough that he could wish for other things. Anchor dropped off one gift in a plain bag.

Inside was a new pair of sneakers and a small strip of clear tape tucked beside them like a joke only Noah would understand. Noah laughed, one short surprised sound, and the room didn’t punish him for it. And that’s how you know a story was worth telling. Not because the villain got what he deserved, because a kid got something he’d forgotten existed.

Room to breathe. “If this story moved you, subscribe for more gentle biker stories that prove protection can look unexpected. Share this video with someone who still believes family stuff should stay private. And in the comments, tell me where you’re watching from and write, ‘Stand with Noah if you believe no child should ever have to beg not to be taken back.’”

News

“THE SCAR THAT SUMMONED 250 OUTLAWS: Girl Repairs Biker’s Harley, Revealing the FRESH WOUND Her Stepfather Gave Her. The Hell’s Angels’ VENGEANCE Ride Began 3 Days Later.”

“THE SCAR THAT SUMMONED 250 OUTLAWS: Girl Repairs Biker’s Harley, Revealing the FRESH WOUND Her Stepfather Gave Her. The Hell’s…

“OUTLAW BIKER STITCH PAID $15,000 to BUY a Child from Traffickers at 3 A.M. What the Hell’s Angels Did NEXT To The Foster System Will Shock You.”

“OUTLAW BIKER STITCH PAID $15,000 to BUY a Child from Traffickers at 3 A.M. What the Hell’s Angels Did NEXT…

“SILENCE SHATTERED: Biker Boss’s ‘Deaf’ Son Was TRAPPED for 7 Years Until a Homeless Teen Risked Everything. The Unseen Object She Extracted Changes EVERYTHING!”

“SILENCE SHATTERED: Biker Boss’s ‘Deaf’ Son Was TRAPPED for 7 Years Until a Homeless Teen Risked Everything. The Unseen Object…

“CHRISTMAS MIRACLE: 7-Year-Old Takes Bat for Biker, and 500 Patched OUTLAWS Roll Up to Demand JUSTICE. The TOWN HUSHED When the Angels Arrived.”

“CHRISTMAS MIRACLE: 7-Year-Old Takes Bat for Biker, and 500 Patched OUTLAWS Roll Up to Demand JUSTICE. The TOWN HUSHED When…

“FATEFUL CHRISTMAS EVE: Desperate Mother Begs for Hot Water… And 200 HELL’S ANGELS Answer the Call. The Unbelievable Retribution the Entire Town Didn’t See Coming!”

“FATEFUL CHRISTMAS EVE: Desperate Mother Begs for Hot Water… And 200 HELL’S ANGELS Answer the Call. The Unbelievable Retribution the…

The Craziest Act of the Blizzard: She Risked Opening Her Door to an Outlaw Gang, But What They Brought Was Even More Terrifying!

The Craziest Act of the Blizzard: She Risked Opening Her Door to an Outlaw Gang, But What They Brought Was…

End of content

No more pages to load