May 10th, 1945. A cold rain falls on a broken German town by the Rhine. The streets still smelling of smoke, wet stone, and fear. Women in torn coats push tired children forward. Ordered to report to the school on the hill where the American conquerors are waiting. For years, they were told the same thing.

“If the Americans come, they will rape you, torture you, kill you.” “Better to die than fall into their hands.” But at the foot of the hill, the wind carries a different smell. Strong coffee, hot meat stew, and fresh bread from American field kitchens. A 12-year-old girl watches her starving mother collapse in the mud, too weak to climb, and waits for the enemy to shout, to strike, to prove the radio right.

Instead, a young American soldier steps forward, kneels in the rain, lifts the German woman gently onto his back, and begins to carry her up the hill like she is someone precious. “Why are you carrying my mother?” the girl cries, her voice full of anger and secret hope. And in that moment, everything she’s been taught about monsters and mercy begins to crack.

If you want to know how this one small act changed a German family, a whole town, and even the way former enemies saw each other, “please like this video, subscribe to support the channel, and stay with me to hear the full story.” The girl’s name was Anna. She was 12 years old and already felt older than that. Her town sat near the Rhine, half stones and half smoke now. Roofs were gone. Windows were just black holes.

When she walked to the water pump, broken glass crunched under her shoes. Inside their small cellar room, the air always smelled the same. Damp earth, coal dust, and the sour steam of thin soup. Her mother, Leisel, boiled potato peels and cabbage leaves in a single dented pot. Most days, that was all they had.

By early 1945, many German civilians were living on less than 1,000 calories a day. Anna could feel that number in her bones. In the corner stood their most precious object, a radio, tall and wooden, its cloth front torn and stained. The speaker crackled and hissed, but it still worked. For years that radio had been their window to the world. Now it was their cage.

The voice that came out of it was always sure, always loud. First it had been Hitler. Then after his death, other men, unknown names, the same tone. They spoke of final victory, I mean of secret weapons, of cowardly enemies. They told them the Americans were animals. “Remember this,” one announcer had said months earlier, his words sharp as knives.

“If the Yankees reach your town, they will take everything.” “They will rape your women.” “They will starve your children.” “Better to die as a German than live as their slave.” Leisel had believed it. She had trusted the uniforms, the flags, the eagle and swastika. Now with the ceiling trembling under distant artillery, she was not so sure.

Still she repeated the warnings to Anna. “If the Americans come,” she whispered in the dark. “Do not look at them.” “Do not speak.” “They are not like us.” But the world outside the cellar told a different story. The trains had stopped. The post no longer came.

Neighbors spoke of cities where 70% of the buildings were gone, burned out by firebombs. Cologne, Hamburg, Dresden. Words that now meant ruins and ashes. One evening, the radio voice changed. It was no longer loud and sure. It sounded tired, almost small. Anna and her mother leaned close, shivering as the announcer read a short, shaky statement. “The Führer is dead.”

“The German armed forces have surrendered unconditionally.” The words hung in the cellar like cold smoke. Outside, no one cheered. There were no flags. Some people cried, others just stared. For years, they had been told Germany would win or be wiped out. Now, neither seemed true. The war was over, and they were still alive.

But in what kind of world? In the days that followed, food grew even scarcer. The ration office stopped opening. The officials disappeared. People broke into warehouses, hoping to find hidden stores. Most found only empty shelves and mouse droppings. A loaf of bread, if you could find it, might cost a whole month’s pay in worthless Reichmarks.

At night, Anna listened to grown-ups whisper above her head. “Americans are across the river.” “They shot SSmen on site, but they gave chocolate to a farmer’s boy.” “It’s a trick.” “First they feed you, then they use you.” Her stomach twisted with each rumor. She did not know which frightened her more. the old story of monsters or the new story that the monsters might be kind. Her father was somewhere far away.

He had gone east with the Wehrmacht in 1943 and never come back. The last postcard said only, “Do not worry.” “We are being moved to the rear for rest.” Then nothing. Maybe he was dead in a field in Ukraine. Maybe he was in a camp behind barbed wire. The radio never spoke of men like him.

Sometimes late at night, Anna would write in a tiny notebook she kept hidden under her blanket. Years later, she would still remember one line. “They tell us the Americans are devils.” “But if they are devils, why do they bring food in their tanks, not just shells?” It was a child’s question, but it cut straight to the center.

Between the world the radio described and the world hunger described, something was wrong. As the shelling faded and the sky grew strangely quiet, another sound rose in the distance. Engines. Many engines coming from the west. The ground began to tremble. Glass rattled in the frames that were left. Leisel grabbed Anna’s hand. “This is it,” she said. “They are here.”

Every story the radio had told, every nightmare it had planted seemed to climb those cellar steps with them as they went out into the gray morning. What waited for them in the town square would not match any of those stories. The Americans came in a long steel line. From the edge of town, Anna saw the first tank appear, wide and low, its tracks grinding broken stones into dust.

Behind it came jeeps, trucks, more tanks. The smell reached them before the sound faded. Diesel fuel, hot metal, and something sharp and foreign from the soldiers’ cigarettes. People came out of cellars and shelters, moving slowly, as if any quick step might draw a bullet.

Old men in worn coats, women with babies on their hips, boys too young to have been sent to the front. Somewhere a dog barked once and then went silent. The soldiers were not what Anna had imagined. The radio had spoken of wild gangs drunk on victory, hungry for revenge. These men looked organized. Helmets sat low over their eyes, belts tight, boots laced, rifles pointed down, not at the crowd.

Some chewed gum, their jaws moving in a bored rhythm that seemed almost disrespectful to the ruins around them. A jeep stopped near the church. An officer stood up, his coat clean despite the mud. Beside him climbed a young German man in a simple suit, hands shaking. He had been taken from somewhere, maybe a prisoner, maybe a refugee, but he spoke English.

The officer called out a few sharp words. The German repeated them, his voice cracking. “All civilians must go to the main square.” “Bring your papers.” “Bring children.” “There will be registration.” “There will be food.” “You must not hide.” “Stay calm.” “No one will be harmed if you obey.” No one moved at first.

Then a woman from the next street, her face thin and gray, whispered, “Food!” like it was a prayer. Slowly, as if pulled by that single word, people began to walk. Anna held tight to Leisel’s hand as they joined the stream. The square had once held a market. Now its stalls were gone, the fountain broken, the stones blackened by fire.

On one side, American trucks formed a wall, big olive green, each able to carry 2 1/2 tons of supplies. Later, Anna would learn that the U.S. Army had moved more than 11 million tons of food and equipment across Europe by the end of the war. At that moment, she only saw mountains of wooden crates. Soldiers jumped down and began to work. Some set up a circle of machine guns, the barrels pointed outward, guarding the square.

Others unfolded tables taken from somewhere, laid them in straight lines, and set up large metal barrels on tripod stoves. Within minutes, a new smell drifted over the crowd. Coffee strong and bitter. Then another fat and onions frying, something meaty boiling in huge pots. Anna’s mouth filled with saliva so fast it hurt. Her stomach cramped as if angry at the memory of real food.

A girl near her muttered, “It’s a trick.” “They will feed us and then take us away.” Her grandmother shook her head slowly. “If they wanted to kill us,” the old woman said, “they have guns.” “They don’t need soup.” At the first table, an American sergeant called out numbers. A German helper repeated them.

Each person who stepped forward gave a name, a date of birth, showed whatever papers they had left. In return, they received a small card with a number and a mark. “Ration card,” someone whispered. “For us, from them.” At another table, soldiers opened crates with swift practiced blows. Cans clinked against each other. Meat, powdered eggs, vegetables.

In 1945, a standard American field ration could reach 3,600 calories a day, more than three times what many Germans were now eating. They handed out not that much of course, but still more than anyone expected. A ladle of thick stew, a slice of white bread, sometimes even a small piece of chocolate, or a cigarette for the older ones. Anna watched a soldier pause when he saw a child in front of him.

The boy’s cheeks were hollow, his coat too big. The soldier looked left and right, then quickly broke his bread in half and slipped the extra piece into the boy’s hand, closing his fingers around it. The boy stared up, eyes wide. The soldier gave a tiny shrug as if to say, “Don’t tell.” “This cannot be real,” Leisel whispered. “They bombed our bridges.” “They shelled our fields.” “Now they feed us meat.”

It was a sharp contrast. The same uniforms that had brought ruin to their town now serving thicker soup than most German kitchens had seen in months. The same army that had crushed the Wehrmacht now arguing among themselves because one man had tried to keep too much food aside for his own unit.

An officer barked at him, pointed to the line of civilians, and ordered the crates opened. Later an old neighbor, Herr Krauss, would remember. “I thought they would steal from us.” “Instead, they guarded the bread from their own men.” “That is when I knew something in our stories was wrong.” Not all the Americans were kind. Some looked at the Germans with flat, hard eyes, and shoved the bowls across the table.

One or two laughed too loudly, pointed at broken statues, took photographs as if they were tourists in a strange ruined museum. But even the cold ones followed rules. No one looted the church. No one dragged women from the line. A few children received candy when officers were not looking.

“Why?” Leisel kept asking under her breath. “Why would they do this?” Anna had no answer. She only knew that the soup was hot, the bread soft, and her hands trembled as she raised the spoon to her mouth. The stew tasted of salt and fat and something smoky. It tasted of a world she had almost forgotten. When the meal was over, the German translator made another announcement.

“Tomorrow, you must all go to the school above the town.” “There will be more questions, more checks.” “Those who are weak will get extra rations.” “You must walk there in the morning.” Anna looked up at the hill where the school stood, its roof half gone, its yard a sea of mud. For her the walk would be easy. For some it would not.

She did not yet know that on that muddy slope her understanding of enemies and mercy would be turned upside down. The next morning the town woke to fog and drizzle. The hill to the school looked steeper under the gray sky. Mud ran in thin rivers down the ruts left by army trucks. Anna and Leisel left early, wore her only coat, too big now because she had lost so much weight.

Before the war she had been strong, carrying sacks of flour in her father’s bakery. Now, after years of short rations, she weighed barely 45 kilos. Her cheeks were hollow, her hands thin as twigs. They joined a slow line moving toward the hill. Old women with scarves tied under their chins, thin boys leaning on sticks, mothers carrying babies wrapped in blankets that smelled of damp and smoke.

Later records would show that in some parts of occupied Germany, more than 40% of civilians were underweight. Anna did not know that number. She only saw it in the way people walked. The road turned upward. Stones slipped under their shoes. The air smelled of wet earth and coal smoke from the few chimneys still working.

Somewhere behind them, an engine coughed far off. A church bell rang once and then stopped. At first, Leisel climbed steadily, breathing hard, but not complaining. After a few minutes, her steps grew shorter. Her hand on Anna’s arm grew heavier. Her boots sank deep into the mud. “Just a little more,” Anna said, trying to sound brave. “We can rest at the top.” “There is no little anymore,” Leisel whispered.

“Everything is a mountain.” They had gone perhaps half the way when it happened. Leisel’s foot slipped on a patch of slick clay. Her knee buckled. She caught herself with one hand, then fell to both knees in the mud. For a moment she stayed like that, head bowed, shoulders shaking. A man ahead of them stopped.

He was missing part of one ear, his coat patched in many places. He looked back, then quickly looked away and kept walking. No one wanted to be the one who delayed the line. No one wanted to draw the eye of the soldiers. “Get up, mama,” Anna begged, her throat tight. “Please, they will be angry if we are slow.” Leisel tried.

She planted the handle of her bag in the mud like a cane and pushed. Her legs trembled, but did not lift her. She sank back down, breathing in harsh gasps. “Go on without me,” she said at last. “You can tell them my name.” “I will come later.” “You can’t stay here,” Anna cried. “They said everyone must come.” She looked up the hill, searching for someone to help.

All she saw were bent backs and lowered heads. Then from behind them came the jingle of metal on metal and the soft thud of heavy boots. An American soldier walked past alone, his rifle slung across his chest. His helmet was tilted back a little. Mud spattered his trousers. As he passed, he saw Leisel on her knees and slowed. For a second, everything went silent for Anna. “This was it,” she thought.

“This is when the stories become true.” The soldier looked from Leisel to Anna. His eyes were not hard, only puzzled. He said something in English that she did not understand. His tone was gentle, questioning. “We’re fine,” Anna said quickly in German, though it was clearly not true. Her heart pounded so loudly she could feel it in her throat.

The soldier hesitated, then he shifted his rifle to his back, stepped closer and made a simple gesture. He pointed at Leisel, then at his own back, then up the hill. He bent his knees, turning so his broad back faced them. Anna stared, not understanding. Then she did. He was offering to carry her mother. “No,” she blurted out, shaking her head.

“No, you can’t.” Shame and fear mixed inside her. Letting the enemy touch her mother felt wrong, like betrayal. The soldier didn’t move away. He stayed crouched, waiting, rain beads forming on the rim of his helmet. He spoke again, a little slower, his voice soft. Anna caught one word she had already heard. “Okay.”

Later, when she was old, Anna would say, “It was the way he waited that broke me.” “He did not order.” “He offered.” Leisel lifted her face. Mud streaked her cheeks. She looked at the soldier, then at her daughter. In that moment, all the posters, speeches, and radio voices seemed very far away. “Help me up,” she said quietly to Anna.

Together, they guided her onto the soldier’s back. He rose in one smooth motion, adjusting her weight with practiced hands. She was so light that he seemed surprised. He hooked his arms under her knees to keep her steady and started up the hill. Anna walked beside them, too stunned to speak. Around them, people turned to stare.

Some frowned, some smiled a little. No one made a sound. The mud squelched under the soldier’s boots. Leisel’s fingers clutched at the rough fabric of his jacket. Anna could smell his sweat under the damp wool mixed with the faint scent of soap and tobacco. His breath came evenly. He did not complain. Finally, the words burst out of Anna before she could stop them.

“Tres to my mut,” she cried. “Why are you carrying my mother?” She knew he could not understand, but she had to ask. Her voice shook with anger, fear, and something like gratitude that scared her more than anger. The soldier turned his head slightly. He heard the feeling, if not the words. For a heartbeat, their eyes met.

Then he did the simplest thing in the world. He smiled, just a small, tired smile. Then he faced forward again and kept walking. At the top of the hill, he knelt so Leisel could slide gently to the ground. She tried to stand straight, wiped her hands on her coat, and whispered, “Danka!” The only word she could manage.

The soldier nodded, said something that might have been, “You’re welcome.” and walked toward the school. Inside, the Americans took names, checked eyes and lungs, weighed people. Those under a certain weight were marked for extra rations. Leisel’s card received such a mark it felt like a strange prize. Anna could not stop thinking about the hill.

“If this was the enemy, if this was the devil she had been warned about, then what had all the shouting voices on the radio been for?” She did not know that far across the ocean, behind other fences, and under another flag, her father was asking the same question. Every few days, the American trucks came back. People lined up at the square with their ration cards.

Leisel’s card had a special red mark now because the doctor at the school had written underweight on his form. It meant an extra ladle of stew, sometimes a spoon of powdered milk. Her cheeks filled out a little. The blue veins in her hands did not stand out quite so sharply. The soldier who had carried her up the hill did not appear again.

Anna looked for him among the helmets and jackets, but could not be sure. They all wore the same color. Still, each time she saw an American bend to speak to a child or help an old man with a bundle, she remembered that short walk through the mud. One morning in late summer, a different kind of truck rattled into town. It was smaller, painted with a red cross on the side.

People gathered fast. The word “post” ran through the streets like an electric current. For months, there had been almost no letters. The old German mail system had fallen apart. Now finally sacks of envelopes spilled out onto a table in front of the town hall. Two German clerks watched by an American sergeant called names.

Schneider Müller Fisher. When the man shouted, “Leisel Weber,” Her mother froze. Then she pushed forward, hands shaking. The envelope they gave her was thin and brown. There were strange stamps in one corner. an eagle, but not the German one. Across the front, in a hand Anna knew like her own, was written their name, an old address. Leisel stared as if afraid it would vanish. Slowly she opened it.

A single sheet of paper slid into her fingers, covered in tight, careful lines. She read the first line silently. Her knees buckled. For a second, Anna thought she would fall again, right there on the flat stones. Instead, Leisel pressed the letter to her chest and began to cry. “It’s from your father,” she gasped. “He’s alive.”

Back in the cellar, she lit a candle and smoothed the paper on the table. The writing was smaller than before, but the same slant. “My dear Leisel, my dear little Anna.” His name was Carl. He had been gone for 2 years now. His voice filled the room through ink and paper. “I am in a camp in America,” he wrote. “in a place they call Texas.”

“It is very hot here and the land is flat as far as the eye can see.” “They brought us by ship across the ocean.” “I thought the Americans would kill us on the way.” “Instead, they gave us oranges.” “I had not seen an orange since 1940.” Anna listened, hardly breathing as her mother read aloud. “They took our names, our ranks.” “They gave us showers, shaved our hair, burned our old uniforms.”

“Then they gave us clean clothes and boots.” “The barracks are made of wood.” “We sleep in bunks, six men to a room.” “The guards are strict, but they follow rules.” “We work in the fields some days.” “Other days we stay in camp.” He wrote of the food in a way that made the thin German soup seem like a bad joke.

“In the morning we get coffee, bread, sometimes jam.” “At midday there is stew with meat and potatoes.” “In the evening there is more bread, sometimes sausage or beans.” “We get about 3,000 calories a day, they say.” “I have already gained weight.” “I’m ashamed to tell you this knowing how you must be living.”

Later, other prisoners would remember the same thing. One of them, a man named Hans, wrote after the war, “We called it the land of plenty behind barbed wire.” “We were captives, but better fed than our own people at home.” The letter went on, “We are allowed to write two letters a month.” “They read everything we write, so I cannot say all I wish.”

“But know this, we are not beaten for sport.” “We are not starved.” “Some guards hate us.” “Others are just bored boys.” “One of them showed us how to play a game they call baseball.” “It is like schlag ball, only stranger.” “He laughed when I missed the ball.” “I laughed when he slipped in the dust.” “It was human.” Leisel’s voice broke on that last word. She wiped her eyes and read on. “They tell us we are protected by something called the Geneva Convention.”

“It is an agreement about prisoners.” “I had heard of it, but did not believe the enemy would obey it.” “Now I must believe my own eyes.” “We are their enemies, yet they follow their own rules.” “Why?” That word why seemed to echo the question Anna had thrown up the hill.

Carl wrote of the sounds of the camp, the clank of mess tins, the crack of bats hitting balls, the low murmur of prayers in the barracks at night. He wrote of smells Anna could almost taste real coffee, fresh bread, cut grass from the camp gardens, where the men grew tomatoes and beans. At night, he added quietly, “I lie awake and think of you.”

“I imagine you in the ruins, hungry, cold.” “The thought makes the food in my mouth turn to ash.” “I wish I could send you even half of what we are given.” “I do not understand a world where a prisoner eats better than his own child.” When Leisel finished, the cellar was silent. The candle flame shook in a small draft.

Somewhere above a truck changed gear with a grinding whine. “He is safe,” Anna said at last. The word felt strange and heavy. “Yes,” Leisel answered. “Safe in the enemy’s hands.” It was another sharp contrast. The Americans who had bombed their bridges were now feeding her father three good meals a day. The men whose tanks had rolled through their fields were counting out sugar and coffee for their captives according to a written law. “This is not what they told us,” Leisel whispered. “Not at all.”

Anna thought of the soldier on the hill, of his steady back, his small, tired smile. She thought of the guards who handed her father bread because a piece of paper told them to treat prisoners as human. If the enemies were not devils, then perhaps the devils were somewhere else. But the the truth about that somewhere else had not yet reached their small town.

It was already rising beyond the ruins in photographs, radio reports, and whispered stories of places with names like Auschwitz and Buchenwald. Soon those names would force Anna and her family to ask an even harder question. Not what the enemy really was, but what they themselves had allowed to happen. The first news came in whispers.

Men who had been soldiers returned in ragged uniforms, thin and quiet. They sat on beer crates in broken courtyards, smoking American cigarettes and talking in low voices. “There were camps,” one said, “not just for prisoners of war, for others, Jews, political people, anyone they didn’t like.” “Lagergeschichten,” another snorted at first. “Camp stories.” But as more men came back, the stories matched.

Too many details were the same. Then the Americans brought proof. One Sunday an officer and the German mayor walked through town going door to door. The officer spoke a few words in slow German. “Men and women.” “Come to the hall.” “You must see this.” That afternoon hundreds of people crowded into the half-roofed town hall. The windows were covered with dark cloth.

In front, Americans had set up a film projector. The machine hummed and clicked. The air smelled of dust, damp coats, and hot metal. On the white sheet they had hung, a title appeared in German, “Der Todesmühlen,” “The Death Mills.” It was a film made from the allies’ own news reels with a voice over added so Germans could not say they did not understand.

Anna sat between Leisel and an old neighbor, Frau Becca. The light from the projector cut through the smoke and landed on the sheet. They saw barbed wire and guard towers, faces like skulls staring through fences, bulldozers pushing heaps of bodies into pits, men in striped uniforms too weak to stand.

British and American soldiers walking through the horror, their own faces gray, the voice said numbers in a calm tone that made them even worse. “6 million Jews murdered, millions of other prisoners, more than 20,000 camps and prisons across Europe.” “This was done in your name.” Some of the older women sobbed.

One man shouted, “Lügen! Lies!” and tried to stand, but two others pulled him back down. Frau Becca covered her mouth with her hand. Her shoulders shook. Later, she would say, “I had heard rumors.” “We all heard something.” “We chose not to look.” “That day, the film forced our eyes open.” “The smell did not reach us, but you could see it.”

“You could see it in the way people moved.” The contrast was brutal. Just months before, the radio had said the Americans were the barbarians, the ones without honor. Now those same Americans were showing Germans what their own state had done. The people who had been called liars were bringing the truth on film.

In the evenings, the town hall filled again, this time for meetings called hearing chambers. Each adult had to fill out long forms answering questions. Were you a party member? Did you work for the SS? Did you give money to Nazi groups? Men who had carefully saved their party badges now hid them or buried them in gardens. Some claimed they had only joined for a job.

Others said, “We did not know.” The Americans sorted them into groups. Main offenders, lesser offenders, followers, exonerated. Statistics for the whole of the western zones would later show that millions of people were judged, but only a small percentage were punished heavily. The rest were sent back to their lives with a new word on their papers, Mitläufer, one who went along. In the church, the pastor’s voice changed, too.

The same man who had once asked God for victory now asked for forgiveness. “We were blind,” he said one Sunday, standing before a cracked window where cold air slipped in. “Or we chose not to see.” “We believed the lie that we were better than others.” “We called our enemies subhuman.” “We sang songs about death for the fatherland.”

“Now we learned that in places not so far from here, human beings were treated worse than animals.” “We must face this.” People shifted on the hard benches. The smell of wet wool and old incense filled the small stone space. After the service in the muddy square, arguments broke out. “We did not know about gas chambers,” one man insisted. “They hid it from us.”

Another, a former teacher, shook his head. “We knew enough.” “We saw Jewish shops smashed.” “We watched our neighbors vanish on trains.” “We heard people say, ‘Oh, good. They’re gone.’” “We let it happen.” “Anyway,” a third snapped. “The Allies bombed our cities.” “Dresden burned.” “Hamburg burned.” “Are they better than us?”

An old soldier with one arm answered softly. “The difference is this.” “They show us what they did.” “They do not deny Dresden.” “We denied everything until they forced it on a screen.” Anna listened to all of it. Her father’s letter lay folded in her pocket. In it, he had written, “We are not all guilty.” She believed that. She also believed what her eyes had seen on the white sheet. At school, when it finally reopened under American orders, new textbooks came.

Old pages about racial science were ripped out. The teacher who had once hung Hitler’s picture over the blackboard now spoke of human rights and law. “There are rules even in war,” he said. “The Americans tried to follow the Geneva Convention for prisoners.” “Our side signed it too, but did not always obey.”

“Now there will be trials in a place called Nuremberg where our leaders will have to answer.” The word trials sounded strange. In the past their leaders had only given orders. Now they would be questioned like common thieves. Outside children played with makeshift balls chewing American gum. Inside adults spoke of guilt and justice. The contrast was almost too much.

One evening, as they pulled weeds in the small garden behind the cellar, Anna finally asked her mother, “Were we all bad?” Leisel paused, dirt on her hands. “No,” she said slowly. “But we were not as good as we thought.” “We believed the men on the radio when they told us others were monsters.” “We did not ask enough questions when our Jewish neighbors’ door stayed locked forever.”

She looked at her daughter. “Remember the hill?” she said. “Remember who carried me?” “The enemy showed more kindness than our own rulers did.” “Let that stay in your mind when people try to make you hate again.” The spell of hatred had not broken cleanly. There were still those who clung to the old lies. But for Anna, the picture was already changing. In the years to come, as the ruins slowly turned into buildings and the gray ration bread turned into loaves from full ovens, that question of who had been enemy and who had been teacher would return again, and it would shape the future of her country. Carl came home on a cold day in

early 1947. The bus that brought him stopped in front of the town hall. Its paint was faded, but on the side you could still see the white star. Men stepped down one by one carrying small brown suitcases. Their boots hit the stones with soft thuds. Anna searched the faces. For a moment she did not know him. Then she saw his eyes.

“Papa!” she shouted. He was broader than before, his cheeks rounder. The gray uniform was gone, replaced by plain clothes the Americans had given him. His coat smelled faintly of ship oil and soap. When he hugged her, his arms were strong. It was a strange, painful contrast. The prisoner looked healthier than the family who had waited for him in freedom.

“They gave us three meals a day,” he told them that night. “Sitting at the small table, sometimes four if we worked hard.” “There was even fruit.” “In Texas, they have oranges piled in boxes like our potatoes once were.”

They gave us three meals a day, “he told them that night.” Sitting at the small table, “sometimes four if we worked hard.” “There was even fruit.” “In Texas, they have oranges piled in boxes like our potatoes once were.” He shook his head slowly. “I wanted to hate them,” “he admitted.” “It would have been easier.”

What do you do with your hate? The war was over, but the Americans stayed. At first as occupiers, then as something else. They ordered old Nazi signs removed. They helped set up new councils. They opened libraries with books banned for 12 years. And then came something bigger.

In 1948, word spread of a new plan from across the ocean. People called it the Marshall Plan after an American general who was now a statesman. Between 1948 and 1952, West Germany received about $1.4 billion in aid. Money, machines, food, coal, trains came loaded not with soldiers, but with grain, steel, and tractors. Ruined factories started again.

By the mid 1950s, industrial production in West Germany had more than doubled compared to the low point after the war. Anna remembered standing on the rebuilt bridge, watching barges move up the rine. Once these waters had carried tanks and guns, now they carried coal, cloth, and cars. “They bombed our factories,” “Carl said, leaning on the rail beside her.” “Now they lend us money to build new ones.”

“What kind of victory is this?” “A different kind,” “Leisel answered.” “One that does not end.” In school, American officers no longer came with films of camps. Instead, they sent teachers to talk about elections, free newspapers, and something called NATO, a military alliance between old enemies and former captives.

In 1955, when West Germany joined that alliance, some old men muttered, “We are now soldiers with those we once fought.” “They came as conquerors,” “the new history teacher said to his class one day.” “But they will leave as allies and we must learn from them as much as they claim to learn from us.” Years turned into decades. The rubble streets became smooth roads.

The school on the hill grew new wings. The mud where leisel had fallen became a paved yard where children played soccer. By the 1960s, German cars were being shipped to American ports. Radios now played American music not as a threat, but as fashion. Anna grew up and became a teacher herself.

She taught history in that same school above the town. On the wall of her classroom hung maps, not portraits of leaders. She taught her students about the camps, the trials at Nerburgg, the Marshall Plan, and the strange fact that after such a brutal war, Germany and America stood on the same side of a new divide.

But every year, she also told one small story. She told them about the gray day in 1945, the muddy hill, her mother’s weak legs, and the American soldier who bent his knees and waited. She told them about the question that had burst from her throat. “Why are you carrying my mother?” Some students frowned. “But didn’t they bomb our cities?” “One would ask.”

“Yes,” “Anna said.” “They did.” “And we must never forget that.” “War brings horror, even when people think their cause is just.” Others asked, “Weren’t we guilty, too?” “We were,” “she answered.” “We believed lies about other people.” “We looked away when neighbors disappeared.”

“The point is not to say one side was all good and the other all bad.” “The point is this.” “Even in the middle of lies and ruins, people can choose to act differently.” One day, many years later, she met an American veteran at a meeting between old soldiers and former civilians. His German was broken but brave.

He spoke of how young men in US uniforms had been shocked by what they saw in Germany, both the ruins and the camps. “We came thinking we knew everything,” “he said.” “We left understanding that power is not the same as wisdom.” “They had come as conquerors,” “Anna later wrote in her diary.” “But they left as students too, students of what hate can do and what mercy can repair.”

By then, the Cold War was fading. A new Europe was forming with open borders between many states. German and American students visited each other’s countries, taking pictures on phones instead of with heavy cameras. Few of them thought of barbed wire when they heard the other nation’s name. Still, Anna kept the memory of the hill alive.

In the end, she would tell her class, “America’s strongest weapon in our town was not its bombs or its tanks.” “It was this.” “They treated us according to their better rules, even when we had not treated others that way.” “They fed prisoners and enemies.” “They carried old women up muddy slopes.”

“That simple choice broke the spell of the radio voices more than any speech could.” She would pause, let the room grow quiet, and then add, “When someone tells you that another group is less than human, remember my mother on that soldier’s back.” “Remember that propaganda can shout, but real kindness does not need a loudspeaker.” “It just bends down, lifts, and walks.”

The story of Anna’s family is only one thread in the huge tapestry of world war too, but it shows a sharp truth. For years, words and symbols had trained Germans to see Americans as beasts. At the same time, Nazi power turned many ordinary Germans into followers of a system that built camps and filled them. When the shooting stopped, the easy story, “we were pure.”

“They were monsters could no longer stand.” Across ruined Europe, millions saw the same paradox Anna saw. The same army that destroyed bridges also built new roads. The same uniform that guarded PWS behind wire also gave those men enough bread to grow fat. This was not propaganda. It was daily life.

And it forced people on both sides to ask new questions. In that painful space between hunger and plenty, guilt and mercy, a different future became possible. Former enemies became partners. The hill above Anna’s town became just another street. But the memory of a soldier carrying his enemy’s wife up that slope remained a quiet proof that even after the worst of wars, people can choose a better play.

News

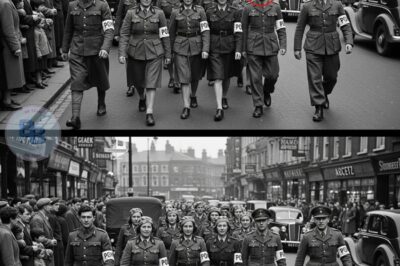

German Women POWs Hadn’t Bathed in 6 Months — Americans Gave Them Fresh Uniforms and Hot Showers

March 12th, 1945, rural Georgia. A warm fog hung over the camp, carrying the smell of pine, diesel, and…

German POWs Thought the British Would Starve Them — But Were Surprised With Food and Fair Treatment

October 1944, 6:47 a.m. Kemp Park, just west of London. A transport lorry coughs to a stop on gravel,…

German Women POWs Shocked to Visit British Cities Without Being Chained

Manchester, England. April 1945. 90 to 47 hours. Lot Schneider stands at the gate of Camp 107. Hands trembling…

Homeless Mom Inherited Her Poor Grandmother’s Mountain House — Then Discovered the Secret Inside

She didn’t expect the letter to find her. People like her weren’t supposed to be located by anything official….

The Hiker Vanished— But a Park Ranger Was Watching Everything From The Ridge

In the blistering heart of the Arizona desert, under a sky so wide it seemed to swallow the world….

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS

In the early autumn of 2021, two sisters from Portland, Oregon, embarked on what was supposed to be a…

End of content

No more pages to load