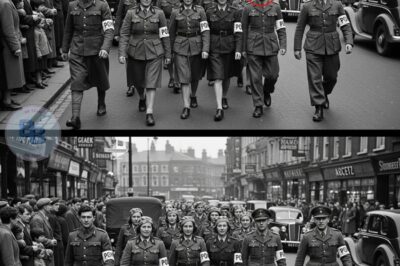

March 12th, 1945, rural Georgia. A warm fog hung over the camp, carrying the smell of pine, diesel, and something else the women could not name. Something strangely comforting. German women stepped down from the train slowly, their uniforms stiff, their hair tangled, their eyes empty after six months without a real bath.

They expected shouting. They expected punishment. They expected everything their officers had always warned them about. But then they heard it running water. Real steady endless water. They smelled fresh soap on the wind. And when they looked up, they didn’t see guards ready to shame them.

They saw a row of private bathhouses built just for them. Nothing made sense. “Why would the enemy give them something they hadn’t had even in their own homeland?” Stay with this story because what happened next shocked every woman who walked through those doors and it will change the way you see World War II. If you enjoy true hidden WWII stories like this, please subscribe, like, and support the channel.

Your support helps me bring you more real stories the history books rarely tell. The train rolled to a stop just after sunrise, its metal wheels scraping softly against the tracks. The air in rural Georgia was warm and heavy, carrying the smell of pine trees, diesel engines, and damp soil. When the box car doors slid open, the German women stepped out slowly, blinking against the brightness.

Many had not felt open air in days. Their uniforms were stiff, their skin hitched. Some had not washed properly in more than six months. They expected shouting. They expected rough hands. They expected the kind of treatment they had seen in Germany, where prisoners were often pushed, driven, or ignored until they collapsed. Instead, the American guards simply stood in place, calm and organized, their rifles held low.

The women later recalled hearing one guard say quietly, “Take your time, ladies,” as if speaking to guests rather than prisoners. One P.W. Anna D. wrote, “It confused me. We had prepared for cruelty, but we found order and patience.” There were 847 women in this group, nurses, clerks, communication assistants, and a few volunteers who had followed military units during the final months of the war. Many carried only a small cloth bundle or a tin cup.

The long trip through France, the Atlantic, and the American railways had left them weak and dizzy. Some struggled to walk, yet no one rushed them. The paradox was immediate. The enemy they had feared was treating them better than their own officers had in months. As they lined up, the women noticed something strange.

The camp looked clean. The roads were swept. The guard towers were painted. Wooden barracks stood in neat rows, each window shining. And near the entrance, a large sign read, “Camp Crawford, U.S. Army P.W. facility.” One woman whispered, “This looks like a village, not a prison.” But the biggest shock stood just beyond the gate.

A row of new wooden buildings with metal roofs gleamed under the sun. Steam drifted out from small chimneys. Pipes rattled softly underground. Buckets of fresh water stood at every corner. The scent of warm soap floated through the air, something many had not smelled since leaving Germany.

These were the private bathhouses the Americans had built specifically for them. Inside each woman would find a stall of her own, a metal shower head, a bench for clothing, and a bar of white soap wrapped in paper. It was a simple structure, but to women who had lived months without a proper bath, it felt unbelievable. One P.W. later wrote, “We were prepared to be stripped in public. Instead, they gave us privacy. It broke something inside me.”

“I did not know whether to cry or be ashamed.” Before entering the bathhouses, the women passed through the medical checkpoint. The American medics worked quickly checking temperatures, writing down names, and examining feet, hands, and skin. They were looking for lice, infections, and malnutrition. Statistics from that day recorded that nearly 40% of the women were severely underweight, and more than half carried untreated skin irritations from lack of hygiene.

The most common issue, exhaustion. One medic wrote in his report, “The women noticed the small details, clean gloves, gentle voices, and the way the medics explained each step. Even the dousing powder, something they feared, was applied carefully with respect for modesty.”

For many, it was the first time in the war that someone had treated their discomfort as something that mattered. The sensory shift was overwhelming. From stale air to warm steam, from sweat and grime to the smooth feel of soap, from fear to quiet confusion. The sound of running water filled the bathhouses as the first women entered. Some hesitated, unsure if it was a trick.

Others touched the walls and felt the heat rising through the pipes. One woman whispered, “Hot water! Real hot water,” as if speaking a forbidden secret. The soap smelled like lemons. The steam softened their skin. For the first time in months, dirt slid away instead of staying trapped in cracks and lines.

What happened in those simple wooden buildings did more than clean their bodies. It washed away years of propaganda. They had been told Americans were animals. They had been told capture meant humiliation, hunger, or death. But the Americans had built these bathhouses on purpose, planned, budgeted, and constructed with care. It wasn’t a trick. It wasn’t a performance. This wasn’t propaganda. It was reality.

And as the women stepped out of the bathhouses wrapped in clean towels, they saw another surprise waiting. The mess hall doors stood open, and the smell of fried eggs and bacon drifted through the air. What they experienced next would challenge them even more deeply. The women walked toward the long wooden building with the rising steam, their feet still unsteady from travel and hunger.

The Americans called it the women’s bath house, but to the German P.W.s, it looked almost unreal. They had expected one large room with cold water and no privacy. Instead, the building was divided into small stalls, each with its own door, its own light, and its own space where a woman could breathe without fear. Inside, warm air wrapped around them like a blanket.

The pipes hummed softly inside the walls. The steam smelled faintly of soap, a clean, simple scent that felt like something from another life. Many of the women stopped just inside the doorway, staring at the rows of private compartments. One P.W. Elise K. later said, “I had slept in barns, cellars, and trains. I had washed in snow. To see a private shower felt like a dream I did not deserve.”

Each stall had a metal shower head, a hook for clothing, and a bench. On every bench sat a small bar of soap wrapped in paper stamped with the U.S. Army logo. The women touched it gently as if testing whether it was real. Some had not felt the smoothness of soap in half a year. Others had forgotten its scent.

The first drops of warm water hit the floor with a soft tapping sound. When the women stepped inside and pulled the chain, the water came down hot and steady. It washed over their shoulders, down their backs, around their arms. Dirt that had stayed on their skin for months finally loosened. Hair that had lost all softness slowly relaxed under the warmth.

For a moment, many simply stood still with their eyes closed, letting the water sink into their bones. They were no longer prisoners, soldiers, or strangers in a foreign land. They were women who had been tired for too long, finally feeling human again. American nurses and medics waited outside the stalls, speaking in calm, polite voices.

They handed out towels, checked for infections, and noted injuries in their records. Reports from that day showed more than 300 cases of mild malnutrition, 120 cases of severe dehydration, and dozens of skin conditions caused by cold weather, unwashed clothing, and travel. But it wasn’t the numbers that stayed in the women’s minds.

It was the tone of the Americans, steady, respectful, and almost gentle. One nurse wrote in her diary, “Most of the women flinched when I approached them. They expected shouting. When I told them they were safe, many cried without making a sound.” There was a clear paradox here. The enemy they had feared was giving them the first peaceful moment they’d had in months.

And even stranger, the Americans had built these bathhouses especially for them. Not for their own soldiers, not for officials, for prisoners. After the showers, the women stepped outside into the sunlight, wrapped in clean towels and new cotton underclothes. Their hair was wet. Their skin felt lighter, as if the water had peeled away more than dirt.

Some held their towels tight, still unsure if kindness was allowed. Others walked slowly, taking quiet breaths of the warm Georgia air, and then another surprise waited for them. Neat tables covered with small items they had not seen in a long time. Combs, brushes, cotton cloths, and simple toiletries. The Americans let each woman take what she needed.

“Choose one,” a guard said politely. The women glanced at each other, confused. They weren’t used to choices. The sounds around them were soft and steady. Boots on gravel, the low voices of guards, the distant whistle of a train. The camp did not feel like the nightmare they had imagined during the war. It felt controlled, organized, and strangely calm.

Several women later admitted this moment broke their beliefs more than any speech could have. They had been told Americans hated them. They had been told capture meant suffering. Instead, the Americans gave them hot water, privacy, and dignity. As the women dressed in clean clothes and stepped into the open yard, they smelled something new drifting through the air.

Something warm, sharp, and unmistakable. It was food. Real food, eggs, bacon, fresh bread, and something sweet they couldn’t identify. The bath house had washed away their fear. Now the mess hall would challenge everything they thought they knew. The smell reached them first. Warm eggs, salty bacon, and fresh bread.

For women who had lived on watery soup and crusts for months, the scent felt almost unreal. They followed the guards toward the mess hall, unsure what they were walking into. Some whispered, “This cannot be for us.” Afraid to hope for too much.

The mess hall was a long wooden building with wide windows that let in the morning light. Inside, metal trays were stacked neatly, and soldiers in white aprons moved quickly behind the serving line. The room buzzed with quiet sounds, pans clattering, coffee being poured, boots stepping lightly on the floor. It did not feel like a place meant to punish anyone. It felt like a place meant to feed people.

When the first German women entered, they froze. On the counter sat large trays of scrambled eggs, piles of crisp bacon strips, bowls of oatmeal, baskets of oranges, and fresh loaves of bread. One woman whispered, “This is for soldiers, not us.”

But the American cook simply nodded and said, “Deek, step forward, ma’am,” as if she were any other guest. The women moved slowly. They held their trays with both hands, almost afraid of dropping them. One P.W. Marta H. later wrote, “I had not seen an orange since 1942. I didn’t think I would ever see one again.”

The Americans served full portions, not leftovers, not scraps, but normal meals. A wartime ration report from Camp Crawford showed that P.W.s received around 2,800 calories per day, almost equal to U.S. soldiers. This was shocking to many of the women who had grown used to German rations that had fallen to as low as 1,000 calories during the last year of the war. The first bite was always the same, a pause, a breath, and then disbelief.

Eggs that were soft and warm, bread that wasn’t stale. Bacon with a taste so rich it almost felt overwhelming. Some women ate too fast, their bodies desperate for nutrition. Others ate slowly, trying to understand how their enemy could offer such abundance. One American sergeant later said, “they looked confused more than anything, like they were waiting for someone to take the food back, but no one did.” The clatter of utensils filled the room.

The German women sat at long tables, eating quietly at first, then speaking in low voices. For the first time in months, the food didn’t carry fear. It carried comfort. A few women cried as they ate, not loud tears, quiet ones that slipped down their cheeks without warning. Hunger had been part of their identity for so long that being full felt strange, almost frightening.

One P.W. admitted later, “I did not know whether to feel grateful or ashamed. We had been told Americans were monsters, but monsters do not feed you like this.” The paradox deepened. They had expected cruelty and received care. They had expected spoiled leftovers and received fresh food. This wasn’t propaganda. It was real life happening right in front of them.

As breakfast continued, and the women noticed more small details, soldiers picking up dropped utensils for them, a cook giving an extra slice of bread to a woman who looked weak, and the steady presence of American guards who kept their distance but treated them with respect. Outside the mess hall, the warm Georgia sun broke through the thin clouds. The women stepped out with fuller stomachs than they had felt in months.

Their legs felt stronger. Their hands were no longer shaking from hunger. The camp around them seemed less frightening than it had in the morning. But this was only the beginning. After breakfast, the Americans gathered the women into the central yard. They were assigned bunks, medical checkups, and work groups.

Some would mend uniforms, others would work in the gardens or help in the laundry house. Yet, the most surprising part wasn’t the tasks. It was the freedom inside the camp. Women were allowed to walk the yard during breaks. They were allowed to speak openly. They were allowed to rest without fear of punishment. And for the first time since the war began, many of them felt something strange growing inside. Calm.

The next part of their journey would show them even more unexpected kindness. Small daily mercies that slowly rebuilt their sense of dignity. The women were guided to their living quarters shortly after breakfast. The barracks were simple wooden buildings, but to the German P.W.s, they felt surprisingly calm and orderly.

Sunlight filtered through the clean windows. The floorboards were swept. The air smelled of wood and warm dust instead of sweat and fear. For women who had slept on cold ground in barns or in crowded train cars, the room felt almost gentle. Each woman received a metal framed bunk with a real mattress, two blankets, and a small pillow.

Many touched the blankets carefully, surprised by how soft they felt. One P.W. Helga R. later wrote, “It was the first bed in months that did not smell of smoke or wet clothes. I lay down and almost cried.” The camp routine began slowly. No one shouted. No one rushed them. Instead, American guards explained the daily schedule in simple steps.

Breakfast, work duty, lunch, rest time, and evening roll call. The clarity itself was comforting. After years of chaos, the predictability felt unusual but welcome. During the first work assignment, the women learned another surprising rule. They would be paid not in American dollars, but in camp script, small paper coupons they could use inside the canteen. The idea felt strange to them.

Prisoners in Germany were rarely paid. But here, every hour of work earned a few cents. The tasks were not harsh. Some women cleaned uniforms, others sewed torn shirts or organized supplies. A few worked in the gardens, pulling weeds or watering plants under the warm Georgia sun. The work was simple and steady, and for many, it brought a sense of purpose back into their tired lives.

One woman said softly to another, “At least we are useful again.” During breaks, the women were allowed to sit on benches in the yard. They watched the guards walk their roots, listened to the wind move through the trees, and breathed in the warm air that carried the scent of earth and pine.

The softness of the environment slowly eased the tension in their shoulders. The camp canteen soon became one of their favorite places. It was a small wooden hut with shelves full of simple goods, writing paper, combs, biscuits, hair pins, and sometimes even small chocolates. The prices were low, and the workers behind the counter often greeted the women with a polite nod or a friendly good morning. It felt strange to be treated with normal courtesy.

One woman bought a small comb and stared at it for a long time. “I have not owned anything new since the war began,” she whispered. That tiny item paid for with her own work made her feel human again. In the evenings, the women gathered near the barracks to talk quietly.

They shared stories about their families, their homes, and what they feared might await them once the war ended. Many had no idea if their loved ones were alive. Some whispered about cities that had been bombed, farms that had been destroyed, and friends who had vanished during the final months in Germany.

Yet in the middle of these heavy worries, small moments of kindness kept appearing. An American guard brought extra paper for a woman who wanted to write to her mother. A medic brought salve for cracked hands. A cook slipped an extra biscuit to a woman who looked exhausted. None of the acts were grand, but together they changed the women’s understanding of their enemy. There was a quiet paradox in every corner of the camp. They had come expecting cruelty.

They found small acts of dignity instead. This wasn’t propaganda. It was reality. The more days they spent in the camp, the more their old beliefs began to crumble. The Americans were strict but not brutal. They were organized but not cold. They followed rules.

and those rules protected the women instead of harming them. At night, when the sky turned dark and the cricket sang outside, the women lay in their bunks and felt a peace they had not known for a long time. For the first time since the war started, many slept without fear of bombs or soldiers breaking down doors. But soon, something else would enter their lives. Letters from home.

letters that carried truths far heavier than anything the camp walls could protect them from. What they read next would shake them more deeply than hunger or fear ever had. The German women woke the next morning to a soft Texas sunrise.

Golden light spilled across the camp yard, warming the dry ground and the wooden barracks. For a moment, they almost forgot where they were. It felt peaceful, too peaceful for prisoners of war. Inside the barracks, Anna sat up slowly. She had barely slept. Her mind kept repeating the same question.

“Why are they treating us like this?” Back home, her mother told her that Americans were dangerous. Her commanders warned her that capture meant humiliation. But here, nothing matched those warnings. She stepped outside and saw an American soldier sweeping the walkway. He was young, maybe 19, and he gave her a small nod. Anna froze, unsure how to answer.

In Germany, soldiers never greeted women like equals. But here, even the guards behaved calmly and spoke politely. Nearby, Marta tied her hair into a simple braid. She had been a nurse during the final months of the war, patching wounded soldiers, listening to cries that never faded. She thought America would feel cold. Instead, she saw men building fences, repairing roofs, and organizing supplies, not for punishment, but to keep the camp safe and orderly. When the breakfast bell rang, the women lined up. A tall American sergeant opened the door to the

mess hall. “Ladies, breakfast is ready,” he said. His voice carried respect, not force. The women exchanged uncertain glances. No German officer ever used such a tone with them. Inside, long tables were covered with plates of scrambled eggs, warm bread, and sliced fruit. A scent of fresh coffee filled the air. The women sat slowly, still unsure if this kindness was a trick.

An older American cook stepped forward and smiled. “Eat well,” he said. “You’re safe here.” That word safe, settled heavily in their hearts. As they ate, they listened. The hall was noisy, but not tense. American guards talked among themselves about baseball, their families and everyday life. It was strange hearing normal conversations after years of war. When breakfast ended, the women were taken to their assigned work areas.

Most were given simple tasks. Sewing uniforms, cleaning linen, helping in the garden. These jobs were not punishment. They were a way to keep routine. The women realized quickly that the Americans followed strict rules against mistreatment. No yelling, no harassment, no abuse. Later that day, a sudden shout startled everyone. “Mail call!” The German women froze.

They had not expected to receive letters in a foreign land. One by one, names were read aloud. Some women stepped forward with trembling hands. Some broke into tears before even opening the envelopes. A few received nothing and lowered their heads quietly. Marta opened her letter slowly. It was short, written by her younger sister.

It said their family was alive but struggling. Marta pressed the paper to her chest and closed her eyes. She whispered a small prayer of thanks. For the first time since her capture, she felt hope. In the yard, Anna watched a group of American women entering the camp. They were volunteers from a local church. They carried books, clothes, and small sewing kits.

Anna stared at them in silence. They walked freely without fear, speaking with confidence and calmness. One of them noticed Anna’s curious look and approached her. “Would you like a book?” the woman asked kindly. Anna hesitated. “For for me?” “Yes,” the volunteer said with a gentle smile. Anna took the book slowly. The cover showed a peaceful countryside scene. She had not held a book with such care since the war began.

The volunteer explained that the women could borrow books anytime. Reading, she said, helped pass long days and eased the mind. As the volunteers left, Anna and the others whispered to each other. They could not understand it. These American women had no reason to help enemy prisoners, yet their kindness felt real.

That evening, the German women gathered outside near the fence. The Texas sky turned deep orange. A warm wind carried the smell of grass and earth. The women spoke softly about their new reality. They talked about the food, the safety, the unexpected respect. For the first time, they allowed themselves to breathe without fear. But beneath that calm was another feeling, confusion.

How could their enemy treat them better than some of their own officers had? How could strangers show more dignity than the people they trusted back home? The war had taught them to expect cruelty. America was teaching them something else, and deep inside, each woman felt it. Their old beliefs were starting to break. The next day began with a quiet surprise. An American officer visited the women’s barracks.

His name was Lieutenant Harris, a calm man with clear blue eyes and a steady posture. He wasn’t there to intimidate anyone. Instead, he carried a clipboard and spoke in a level voice. “Ladies, today you will have a health check,” he said. “It is routine. Nothing to fear.” The women tensed. In Germany, medical inspections often meant humiliation.

Some felt their stomach twist at the thought. But when they entered the small medical building, they found something different. Two American nurses greeted them. They wore clean white uniforms and spoke softly. Their instructions were polite and simple. They measured weight, checked blood pressure, and examined hands for injuries. They offered blankets if anyone felt cold.

Not once did they raise their voices. One nurse gently touched Anna’s wrist. “You’re dehydrated,” she said. “Drink extra water today.” It was the first kind medical advice Anna had heard in years. When the health check ended, the women stepped outside feeling strangely lighter. No shame, no threats, just care, the kind they once gave to others during the war.

Later in the day, the women were allowed to visit the camp library. The room was small, but full of books donated by local families. A young American corporal explained the rules. Each woman could borrow two books at a time. They must return them in good condition. The German women walked slowly between the shelves. Some touched the books as if they might disappear.

Marta chose a medical text, hoping to refresh her old knowledge. Anna picked a novel with a simple English title. She could not read English well yet, but she liked the cover. As the women prepared to leave, the corporal added something unexpected. “If you need help with English,” he said, “we have classes twice a week.”

“You can join if you like.” English classes for prisoners. The idea felt unreal. Back home, no one ever taught them a foreign language simply to help them live more comfortably. Yet here, the Americans seemed to believe that learning could ease tension and help the women feel human again. That afternoon, the women worked in the camp garden.

The soil was soft from recent rain. They planted vegetables under the supervision of a middle-aged American sergeant. He explained each step with patience, pointing to the tools and showing the proper way to space the seeds. One of the German women accidentally dropped a tool. She stepped back quickly, expecting a harsh reaction. Instead, the sergeant bent down and picked it up for her. “It’s all right,” he said simply.

“Happens to everyone.” The woman stood frozen for a moment. His tone held no anger, no insult, only a matter-of-fact kindness she had not heard during her service in Germany. When the day’s work ended, the women returned to the yard for evening roll call. The sun hung low, warming the fences in a golden glow.

A few birds perched on the wires. The camp’s atmosphere felt quiet, almost peaceful. During roll call, Lieutenant Harris addressed the group. “Tomorrow,” he said, “you’ll be allowed limited access to the recreation area. It has sewing tables, a small music corner, and painting supplies. Use them responsibly.”

“They’re for your well-being,” the women whispered among themselves. Recreation, music, art. These were things they had almost forgotten during the war. Back home, such comforts disappeared beneath bombings, shortages, and fear. Now in enemy hands, they were being offered again.

That evening, inside the barracks, the women sat on their bunks, talking quietly. The day had given them much to think about. Every new experience pushed them further away from the warnings they once believed. Nothing here matched the dark stories told by their leaders. Nothing matched the harsh training they received. Anna stared at the ceiling for a long time.

She remembered her commander telling her that Americans treated German prisoners like animals. She remembered the fear she felt when captured, thinking the worst was coming. But now, after only a few days, everything felt different. She ate well. She had clean clothes. She received medical care, books, and space to breathe. Even the guards seemed more like watchful caretakers than enemies.

Across the room, Marta quietly said, “If our families could see this camp, they wouldn’t believe it.” Anna nodded. “I don’t believe it myself.” Silence settled for a moment before Marta added, “Maybe the war taught us only one side of the world.” Those words stayed with Anna long after the lights went out.

Outside, the wind moved softly through the fences. The American flag shifted in the darkness. Somewhere in the distance, a train whistle echoed, reminding everyone that life beyond the camp continued. But inside the barracks, something more important was happening. The German women were slowly learning that their enemy did not see them as enemies anymore.

They saw them as human beings. And that simple truth was changing everything they thought they knew. In the end, the women who arrived in fear left with a new understanding of the world. They came expecting punishment, humiliation, and revenge. Instead, they found open doors, warm water, clean clothes, and people who spoke to them with respect.

What began as simple survival slowly turned into a lesson about dignity. Many later said that America changed them more than any speech or officer ever had. They had come as soldiers shaped by a regime that told them the enemy had no mercy. But behind the fences, they discovered that mercy was real and it was powerful.

They came as conquerors. They left as students. In the end, America’s greatest weapon was not force. It was humanity.

News

“Why Are You Carrying My Mother?” — German Woman POW’s Daughter Shocked by U.S. Soldiers’ Help

May 10th, 1945. A cold rain falls on a broken German town by the Rhine. The streets still smelling…

German POWs Thought the British Would Starve Them — But Were Surprised With Food and Fair Treatment

October 1944, 6:47 a.m. Kemp Park, just west of London. A transport lorry coughs to a stop on gravel,…

German Women POWs Shocked to Visit British Cities Without Being Chained

Manchester, England. April 1945. 90 to 47 hours. Lot Schneider stands at the gate of Camp 107. Hands trembling…

Homeless Mom Inherited Her Poor Grandmother’s Mountain House — Then Discovered the Secret Inside

She didn’t expect the letter to find her. People like her weren’t supposed to be located by anything official….

The Hiker Vanished— But a Park Ranger Was Watching Everything From The Ridge

In the blistering heart of the Arizona desert, under a sky so wide it seemed to swallow the world….

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS

In the early autumn of 2021, two sisters from Portland, Oregon, embarked on what was supposed to be a…

End of content

No more pages to load