October 1944, 6:47 a.m. Kemp Park, just west of London. A transport lorry coughs to a stop on gravel, still wet from night rain. 32 men climbed down, stiff-legged, hands zip tied with canvas strips. Feldwable Hans Müller, 23, captured three days ago in Normandy, expects dogs, expects batons, expects the England his officers promised, a island of vengeance where German soldiers are left to rot.

Instead, a British sergeant approaches with a clipboard and a dented thrus. “Tea while we sort the paperwork. You’ve had a long ride.” Miller stares at the tin cup. Steam rises into cold air. The sergeant pours without ceremony. Moves down the line. No one drinks at first. They wait for the trick. It doesn’t come. The propaganda had been clear.

British captivity meant starvation. Beatings and sellers. Forced marches until you dropped. The Geneva Convention was a scrap of paper. the allies used for news reels then ignored in the dark. Some PS had seen the leaflets, images of skeletal prisoners, warnings that surrender meant certain death. Officers repeated it in the last briefings before the collapse.

“Better to die fighting than beg from the English.” But here, in a processing tent, still smelling of canvas and disinfectant, the cupboards were stalked. The medical officer was methodical, not cruel, and the tea kept coming. They were registered by name, not number. A clerk, bored, methodical, asked Miller to spell his mother’s surname for the contact file.

He did, haltingly, expecting a slap for the delay. The clerk just nodded and moved on. Personal effects were cataloged, not confiscated. Wedding rings, photographs, a harmonica, all tagged, stored, receded.

In the corner of the processing hall, an older prisoner sat with his boots off, feet wrapped in gauze by a British orderly who worked without comment. Miller watched. He had been trained to see enemies. He saw a man doing a job.

The tea offered again at the barracks door was bitter, overbured, poured from it shipped enamel pot that probably served a thousand men before him. He drank it this time. It was still warm. Britain’s P system wasn’t sentiment. It was policy.

Directives from the war office were explicit. Security, intelligence, diplomacy, morality in that order. But morality was on the list. The goals were practical. Security. Stable camps reduce escape attempts and unrest. Intelligence. Cooperative. Prisoners provide operational details. Reciprocity. Treat PS well.

German camps might do the same for captured British soldiers. Standards. Civilized nations don’t abandon principle under pressure. Over 400,000 German PSWs would pass through British custody by war’s end. Quarterly Red Cross inspections documented conditions. Caloric intake met or exceeded Geneva minimums, often around 2,800 to 3,000 calories daily for working prisoners. Mortality rates remained extraordinarily low, especially compared to other theaters. Decency wasn’t charity. It was discipline. It was restraint encoded as doctrine. And it worked. If you’ve made it this far, hit subscribe. We’re building the most grounded W2 archive on YouTube, one forgotten story at a time.

Processing took 2 hours. Medical exams were thorough. Lice check, dental inspection, tuberculosis screening. A German-speaking liaison explained the camp rules in flat bureaucratic sentences. Work was mandatory. Cooperation was rewarded. Escape attempts were punished with solitary confinement. No beatings, no summary courts.

One commonant was known to say, “The barbed wire is the punishment. We don’t need to add to it.” Miller was assigned to Hut 7, bed 14. The mattress was thin but clean. A wool blanket, British Army issue, weighted folded at the foot. Then came the first meal. Boiled potatoes, tinned meat, bread with margarine, wheat coffee. It wasn’t a luxury, but it was enough.

Some men ate slowly, tasting every bite as if testing for poison. Others ate in silence, tears tracking down their face as they turned toward the wall. No one spoke about the tea, but everyone remembered it.

By November, Miller was part of a 60-man work detail assigned to a dairy farm in Somerset. The work was real, mucking stalls, repairing fences, hauling hay bales during the autumn harvest. Hours were long, 6 to 8 daily, but within Geneva limits. Supervision was light. The farmer, a man named Dalton, spoke little and expected competence. “You break it, you fix it, you slack off, you’re back to camp.” No threats, just standards.

Miller found himself taking pride in the work. The fences he mended stayed mended. The gates he rehung didn’t sag. Extra rations came on heavy work days. An additional slice of bread, sometimes cheese. Honest work for honest treatment. It was a contract he hadn’t expected to sign.

Dalton’s wife left tea on the fence post most mornings. Not for friendship, just efficiency. “Keeps the man from dragging their feet before lunch.” But after 3 weeks, she added biscuits. After 2 months, Mueller and two others were invited to eat Sunday dinner in the kitchen while Dalton listened to the BBC. No guards, no locks, just the unspoken deal. You’re trusted until you’re not.

Mueller never considered running. Where would he go? Back to a war that was already lost. He fixed the tractor instead. Dalton watched, arms folded, then handed him the toolbox the next time it stalled. Trust, it turned out, could be earned in grease and bent metal.

In January 1945, Mueller caught pneumonia. The camp hospital was clean, heated, staffed by a British doctor and two nurses who treated him exactly as they treated the guards. antibiotics, warm compresses, soup delivered twice daily. The doctor, a man nearing 60, too old for frontline service, checked Mueller’s lungs with a stethoscope and made notes in a ledger that recorded every prisoner’s health with the same bureaucratic care as a school teacher’s attendance book. No speeches, no sermons, just medicine.

When Mueller thanked him, the doctor shrugged, “You’re a patient. I’m a physician. That’s the job.” Mueller returned to the farm two weeks later, five pounds heavier, and carrying a small respect he couldn’t quite name.

The camp chaplain, Church of England, mildmannered with thinning hair, organized a Christmas Eve service. Attendance was optional. Mueller went. So did most of Hut 7. The chaplain read from Luke. A German prisoner played accordion. Someone produced a harmonica. Silent Night was sung in two languages. The Harmony clumsy but earnest. Afterward, the guards distributed cigarettes and extra tea. No propaganda, no speeches about Brotherhood of Man, just cigarettes, biscuits, and a moment where the war felt smaller than the room.

One guard, young, barely 20, stood at the back and applauded softly when the music ended. Mueller noticed.

Prisoners were allowed to write home once a month. letters were censored but lightly. Mueller wrote to his mother in careful neutral sentences. “I am well. The work is fair. We are treated according to law. Do not believe what you hear about England. It is not what they told us.”

His letter reached her in March 1945. Passed through Red Cross channels. She shared it with neighbors. The propaganda minister’s promises began to crack one envelope at a time. By summer, some German civilians were writing back saying, “If you are alive and fed, perhaps surrender is not the end we feared.”

Information, it turned out, traveled both ways. The camp library held 400 books donated secondhand, multilingual. Mueller borrowed an English grammar primmer, then a novel by Dickens, which he read slowly, dictionary in hand. Some prisoners organized a chess club. Others formed a choir. One man, an engineer before the war, taught mechanical drawing in the evenings. Guards occasionally attended, curious. These were small freedoms, but they signaled something larger. You are still human. You still have agency. The barbed wire remained. The guards remained, but within the wire, there was room to grow.

In February, a guard lost his temper during a work detail and shoved a prisoner who dropped a crate. The guard was reprimanded the same day, removed from duty for a week. The camp commandant made the announcement at evening roll call. “Standards apply to all of us.” No elaboration, no apology tour, just accountability. Mueller filed the moment away. In his own army, such an incident would have been ignored, or the prisoner would have been punished for clumsiness.

Here, the system bent toward fairness, not perfectly, but consistently. Drop a comment below. What surprised you most about this story? We read everyone.

By spring 1945, restrictions had loosened. Work details no longer required armed escorts. Mueller and others walked unguarded to the farm each morning. A two-mile trek through fields still wet with dew.

Dalton handed him the tractor keys one morning without comment. “Plow the north field. I’ll check it this afternoon.”

No supervision, no test, just a job. Mueller plowed straight rows, checked the fuel, parked the tractor in the barn. When Dalton inspected the work, he nodded once, “Good.”

But Mueller felt something shift inside him, something close to pride. During the harvest, several prisoners volunteered extra hours, not for rewards, just because the work mattered, and leaving it unfinished felt wrong. Competence earned respect. Respect earned trust. Trust became the foundation for something neither side had expected. Mutual regard.

Mueller sat on his bunk one evening in April, holding the chipped enamel cup that had become his personal mug. The war was ending. Everyone knew it. Germany was collapsing. The propaganda machine had lied about everything. The wonder weapons, the inevitable victory, the subhuman enemies. If they’d lied about the British starving prisoners, what else had been false? Years later, decades later, he would tell an interviewer, “I went into that camp expecting to die. I came out questioning everything I’d been taught. Not because someone preached to me, because I was treated like a man.”

That was the pivot. Not a lecture, not a leaflet, just consistency, restraint, the steady application of civilized standards. It planted a seed. And seeds given time grow. The war in Europe ended in May 1945.

Repatriation began slowly. Logistics, vetting, transportation. Many PS weren’t sent home until 1946 or 1947. Some volunteered to stay temporarily, continuing farm and reconstruction work while Germany rebuilt. Some never left. Mueller returned to Germany in late 1946. He found his mother alive, his town in ruins, his country trying to remember what it had been before the madness.

He kept in touch with Dalton for 30 years. Christmas cards, brief letters, updates about harvests and grandchildren. He never forgot the tea or the blanket or the moment a British sergeant handed him a cup and said, “You’ve had a long ride.”

Civilization is not the absence of conflict. It’s what you do when conflict gives you permission to abandon principle. Britain didn’t treat German P well because Germans deserved it. They did it because they deserve to remain who they were. Victory without vengeance, order without cruelty, strength measured not by the pain you inflict, but by the restraint you maintain when no one would blame you for inflicting it. Mueller carried that lesson home in 1946, wrapped in a wool blanket in the memory of bitter tea.

The barbed wire came down. The cup remained.

News

“Why Are You Carrying My Mother?” — German Woman POW’s Daughter Shocked by U.S. Soldiers’ Help

May 10th, 1945. A cold rain falls on a broken German town by the Rhine. The streets still smelling…

German Women POWs Hadn’t Bathed in 6 Months — Americans Gave Them Fresh Uniforms and Hot Showers

March 12th, 1945, rural Georgia. A warm fog hung over the camp, carrying the smell of pine, diesel, and…

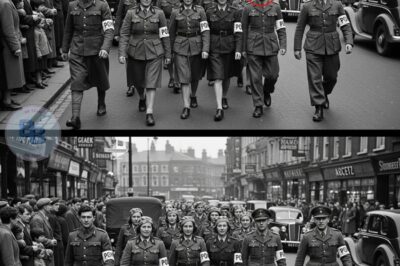

German Women POWs Shocked to Visit British Cities Without Being Chained

Manchester, England. April 1945. 90 to 47 hours. Lot Schneider stands at the gate of Camp 107. Hands trembling…

Homeless Mom Inherited Her Poor Grandmother’s Mountain House — Then Discovered the Secret Inside

She didn’t expect the letter to find her. People like her weren’t supposed to be located by anything official….

The Hiker Vanished— But a Park Ranger Was Watching Everything From The Ridge

In the blistering heart of the Arizona desert, under a sky so wide it seemed to swallow the world….

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS

In the early autumn of 2021, two sisters from Portland, Oregon, embarked on what was supposed to be a…

End of content

No more pages to load