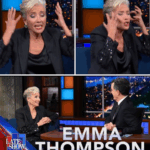

The gloves are off! Dame Emma Thompson—an Oscar-winning screenwriter—has declared her “intense irritation” with Artificial Intelligence, revealing the astonishing reason why a simple Word document keeps trying to rewrite her masterpieces. Discover the true, terrifying story of how an early computer once annihilated her entire Sense and Sensibility script, and why her defiant, longhand process is a desperate fight for the soul of human creativity.

‘Intense Irritation’ and a £60 Payday: Emma Thompson’s Fierce Defense of Human Creativity Against the AI Revolution

In a world increasingly dominated by the silent, relentless churn of algorithms and automated thought, Dame Emma Thompson remains a brilliant, fiercely human anachronism. The Academy Award-winning screenwriter, beloved actress, and cherished national treasure recently sat down with Stephen Colbert on The Late Show, and in a span of just a few minutes, she managed to articulate the profound, often-unspoken anxieties gripping the creative community. Her conversation was a thrilling defense of the messy, imperfect, and intensely personal process of human creation, contrasting a gritty, low-paid past with a terrifying, AI-driven future.

Thompson’s journey, one she traced with her characteristic blend of wit and poignant honesty, began not on a lavish film set, but in a notoriously dive-like venue on her 25th birthday, a story that perfectly illustrates the raw, cash-in-hand origins of artistic struggle.

The Baptism of Fire: Thatcher, Herpes, and the Brown Envelope

Colbert’s question was simple: “Do you remember the first time you got paid to be funny?” Thompson’s reply was instantaneous and richly detailed, a narrative thread that cut through the polite talk show formality straight to the heart of a young artist’s validation.

The setting was the Cuden warehouse, a place she dryly advised the audience to “Never go.” The year was a time of particular social and political friction, and her comedy was a product of that era, focused on two subjects that were, in her words, “both very big at the time” and “equally unpleasant and difficult to get rid of”: Margaret Thatcher and herpes. This anecdote, delivered with a mischievous twinkle, immediately sets the tone for Thompson’s career: unafraid to tackle the difficult, the painful, and the deeply political with a sharp, comedic edge.

But the emotional core of the story was the payment itself. For her efforts—for standing alone with a microphone and a collection of defiant, dark jokes—she was paid “60 quid,” delivered in a “brown envelope” of cash. The image is instantly iconic: the future Dame, the eventual Oscar-winning writer, receiving her comedic baptism fee in an unceremonious fashion that speaks volumes about the hustle and the low-stakes beginnings of genius.

The moment resonated deeply with Colbert, who shared his own story of a similar first payment at Second City, emphasizing the “amazing feeling” of realising that “this money came out of me standing with some words and a microphone.” It is a shared, universal truth for all creators—the first time a private thought, a joke, or a story is deemed valuable by the outside world. It is the moment an artist is born. For Thompson, that £60 was the seed of an entire, celebrated career, a testament to the idea that true artistry starts with a willingness to be vulnerable and, yes, a little bit unpleasant.

The Connection Between Brain and Hand: A Defense of Longhand

The conversation then took a sharp turn from nostalgia to pressing current affairs: the looming shadow of the AI revolution and its impact on writers. Thompson’s response was not cautious or diplomatic; it was a visceral reaction: “Intense irritation. I cannot begin to tell you.”

Her irritation stems from a philosophical disagreement with the very nature of automated, digital creation. Thompson revealed her deeply personal and profoundly analog writing process: she writes longhand, using legal pads or old scripts. This isn’t just a quirky habit; it’s a fundamental belief in the “connection between the brain and the hand.” For Thompson, the physical act of forming words, of moving a pen across paper, is intrinsically linked to the creative thought process and the neurological retention of material. She noted that she must memorize her acting parts by hand, or she won’t “get it.” It’s an assertion that creativity is an artisanal craft, a tactile, muscular effort that computers can never replicate.

This commitment to the hand-written word puts her in direct conflict with the “helpful” features of modern word processing software, which she sees as the frontline foot soldiers of the AI revolution. She recounts a moment of pure digital hubris, where her word document, upon receiving her freshly written prose, constantly interjects with the deeply offensive query, “would you like me to rewrite that for you?”

“I don’t need you to rewrite what I’ve just written!” she exclaimed, voicing the frustration of countless writers whose work is instantly treated as flawed or incomplete by an algorithm. This sentiment speaks to a larger cultural anxiety: the fear that technology is no longer just a tool for artists, but a condescending partner that seeks to edit, homogenize, and eventually replace the original human voice. Her annoyance is not just personal; it is a battle cry for the autonomy of the human creative spirit.

The Ghost in the Machine: The Sense and Sensibility Near-Disaster

Thompson’s current “intense irritation” is perhaps rooted in a terrifying technological episode from her past—an anecdote so dramatic it nearly derailed the completion of her Oscar-winning screenplay for Sense and Sensibility. The story serves as a kind of technological cautionary tale, proving that even in its infancy, the machine harbored a certain destructive malice.

She recalled working on one of the “big old square computers,” which she fondly remembers as being “a little bit more friendly” than modern machines—a nostalgia that now seems deeply ironic. While finishing the script, which would go on to define her career as a writer, she stepped away to use the restroom, or “the loo,” as she charmingly put it. This small, human necessity was the opportunity the computer needed.

Upon returning, she found the entire Sense and Sensibility manuscript had vanished. It had completely “gone,” having been converted into nothing but “sort of hieroglyphs.” The panic of that moment—the sheer terror of realizing years of work was instantly erased—is palpable. The image she paints is legendary: a panicked, Oscar-winning writer, rushing out of her house, still in her dressing gown, to find the sanctuary of a taxi and the help of a friend.

Her savior was the beloved British actor and writer Stephen Fry. He calmed her, saying, “Oh, it’ll be fine,” and spent eight agonizing hours attempting to recover the lost file. His efforts, though heroic, yielded a bizarre, unusable result: the entire 18th-century period drama emerged as a single, impossibly long sentence. Thompson joked that the computer had deliberately “taken it and hidden it behind the wainscoting,” an intentional act of spite from the ghost in the machine.

That terrifying episode—a digital sabotage that almost robbed her of one of the crowning achievements of her career—was a stark, early lesson in the unreliability and potential malevolence of technology.

The Unstoppable Human Spirit

From her early, gritty performances in a questionable venue to her current, vehement stand against AI, Emma Thompson’s career is a powerful argument for the tenacity and necessity of human art. The £60 she earned on her 25th birthday, cash in a brown envelope, bought her the right to keep creating, to keep telling difficult, hilarious, and moving stories. That cash, earned by tackling challenging subjects with her singular voice, stands in stark contrast to the sterile, “helpful” prompts of today’s AI.

Her story is a rallying cry for all creators: hold the line. Believe in the visceral connection between the brain and the hand. Because if a machine could rewrite Sense and Sensibility into a single sentence, or try to convince an Oscar winner that her first draft is flawed, then the work of the artist is more vital than ever. The future of genuine, human-sparked creativity depends on the stubborn, intense irritation of people like Dame Emma Thompson.

News

NIGHTFALL OF INFORMATION: Elon Musk’s ‘De Niro Ban’ EXPLODES Social Media – Turning a Joke into a Global Wave of Hatred

Musk vs. De Niro: The clash between two of America’s most powerful icons never actually happened, but on the…

1,000% Not True: Derek Hough Fires Back at Ryan Seacrest Over ‘Wheel of Fortune’ Vandalism Claim, Calling Out ‘Disrespect’ to the Iconic Set.

The Spinning Feud: Derek Hough Rages Against Ryan Seacrest’s Claim of On-Set Disrespect at the ‘Wheel of Fortune’ In the…

THE WHEEL IS BACK! Wheel of Fortune Season 43 Takes Flight: What Secrets Await Ryan Seacrest and Vanna White’s Record Run?

THE WHEEL OF FORTUNE RETURNS WITH A STORM OF ENERGY! Season 43 Is About to Explode On Screen: Maggie Sajak…

Hoa Karen pushed the poor black waitress into the swimming pool to make everyone laugh at her, but then a millionaire stepped in and did something that left everyone speechless…

Hoa Karen pushed the poor black waitress into the swimming pool to make everyone laugh at her, but then a…

My Own Mother Attacked Me With a Metal Statue — But When I Saw What She’d Done to My 3-Year-Old Daughter… I Swore I’d Never Forgive Her

After years of hardship, my husband and I finally bought our dream home. During the housewarming party, my own sister…

BOMBSHELL! Is Ryan Seacrest ‘Out’? Pat Sajak Demands His Crown Back and the Truth Behind the Backstage Feud with Vanna White!

Wheel of Fortune Shocker: Ryan Seacrest’s Future in Question? The Real Reason Behind Rumors of “Quitting the Game” He’s barely…

End of content

No more pages to load