“Come With Me” — The Story of Silas Granger and Marabel Quinn

Wyoming, January 1877. The wind howled through the snow-covered peaks of the Snowhorn Mountains like a wounded beast. The sky was a sharp gray, and the whole world seemed frozen in an icy breath.

Silas Granger, a solitary rancher with steely eyes, rode slowly along a trail that no one had trod in days. The horse’s hooves sank into the snow up to its ankles, making a dull crunch with each step.

Then he heard something else. Not the wind. Not the howl of a coyote. But a sound more fragile, more human—a cry.

First one, then several. The cries of a baby.

He tugged on the reins, bringing his mount to a halt. His piercing gaze searched the pines for the source of the sound. He dismounted, clutched his coat, and followed the sound through the trees. The cold bit at his cheeks, snow seeped into his boots, but he pressed on without hesitation.

The path suddenly opened onto a clearing. There, near an old, rust-eaten fence post, a woman was tied up, her arms bound behind her back with barbed wire.

Her face was deathly pale, streaked with purplish bruises. Her cracked lips barely whispered a breath. Snow clung to her eyelashes. At her feet lay three small bundles wrapped in damp cloth—newborn babies.

Silas felt his heart sink.

He knelt beside her.

“Don’t… leave them…” she whispered weakly. “Don’t let them take them… my girls…”

He removed his gloves and placed two fingers on her neck: a faint heartbeat, but definitely there.

“You’re coming with me,” he said in a deep, steady voice.

He pulled his knife from his boot and cut the wire. The metal slashed into her flesh as it came away, but she didn’t cry out. Not even a whimper.

When he lifted her into his arms, she collapsed against him, unconscious. He carried her like a child, then gathered the three infants, tucking them into the folds of his jacket, against his chest. Their breaths were so weak they seemed about to stop.

He climbed back onto his horse, holding the woman in front of him, the babies between them, and urged the animal toward the ridge. The wind whipped their faces, the snow raged, but Silas listened only to the beating of his own heart.

“You won’t die here, not on my land,” he whispered into the wind.

His cabin, perched halfway up the slope, was nothing more than a shelter of worn planks, but it offered what the mountain denied: a roof, a fire, and the promise of a little warmth.

He shoved himself inside, laid the woman on a bed of blankets near the hearth, and lit a fire with a sure hand. The flame slowly revived, chasing away the shadows and the cold.

The infants shivered. He heated some goat’s milk, poured a few drops onto a wooden spoon, and fed each child with infinite patience.

Then he returned to the woman. He cleaned the wounds on her legs and wiped away the dried blood. The silence of the cabin was broken only by the crackling of the fire and the children’s faint sighs.

When she regained consciousness, her lips barely moved. “My name is… Marabel… Marabel Quinn.”

Silas nodded.

“Silas,” he replied simply.

His gaze drifted to the sleeping children. A barely perceptible smile crossed his bruised face. Silent tears rolled down his cheeks.

The days passed. The snow continued to fall, but the cabin breathed life into it.

Silas hunted, repaired the walls, tended the fire. Marabel, too weak to move, listened to the sound of his footsteps as one listens to a prayer.

One morning, as the gray light filtered through the planks, she spoke.

“I was seventeen when I married Joseph Quinn,” she said, her voice hoarse, almost choked.

“He was thirty-four. Rich. My father said I was blessed. I believed him too. At first.” “

Silas listened without a word, slowly sharpening his blade.

“He treated me like property. Not a wife. With the first girl, he frowned. With the second, he stopped speaking to me. With the third…” She trailed off. Her gaze drifted toward the fire.

“He beat me. Then he tied me to this post, saying that if the snow didn’t kill me, it meant I deserved to live.”

A heavy silence followed her words.

Silas put down the blade. He approached, knelt before her, and took her bruised hand in his.

“Here,” he said softly, “your daughters are the most precious thing.”

She looked at him, tears welling in her eyes. And for the first time, she believed his words.

Spring was slow to arrive. But it came.

The snow gradually melted, revealing tufts of green grass. The girls—Eloise, Ruth, and June—were growing, laughing, crying, breathing. Marabel rep

She regained her strength. She walked, cooked, and sometimes sang.

Silas, meanwhile, worked outside, repairing fences, setting traps, and returning each evening with wood, a rabbit, and sometimes a bouquet of wildflowers, which he never mentioned.

One evening, she surprised him carving wood at his workbench. He worked silently, focused. The next day, she discovered three cedar plaques above the cradle:

ELOISE — RUTH — JUNE

The hand-carved letters gleamed in the firelight.

Marabel brought her hand to her mouth to stifle a sob. It was the first time someone had given their daughters a name that would last.

But the peace was only a lull before the storm.

One morning, a rider came up to the cabin: Hattie, the neighbor from the valley.

“Joseph Quinn has sent men after you,” she said. “He says you’re crazy, that you stole his children. They’re coming, Marabel. Four of them. And they’re not going to talk.”

Silas said nothing. He nodded, thanked Hattie, and then spent the rest of the day fortifying the cabin. He reinforced the door, prepared dry food, and stowed weapons, but his face remained calm.

The next day, the wind died down. The silence was too perfect. Then came the hooves.

Four riders.

Silas stepped out. The leader, a man with a scar across his face, raised his voice:

“This woman doesn’t belong to you, Granger. She’s Joseph Quinn’s wife. And his daughters, his blood. We’ve come for them.”

Silas fixed his eyes on hers.

“She never belonged to anyone.” “

The thunder of the wind answered his words.

The men left—for a time. But he knew they would return.

A few weeks later, they came back.

The snow was falling again, thick and wild.

Silas saw their silhouettes through the window.

He turned to Marabel:

“Take the girls. Follow the stream. Stay low. Don’t come back until you find the sheriff.”

She wanted to protest, but he cut her off with a look. He handed her a short knife.

“If they catch you, don’t hesitate.”

She nodded, her heart pounding.

Then she disappeared into the storm, her three children clutched to her.

Silas stayed. He lit a fire outside, left tracks to mislead them. Then he waited.

The first knock at the door made the walls tremble.

Joseph Quinn entered, revolver in hand, his eyes burning with hatred.

“She belongs to me. Do you understand that? My daughters, my name!”

Silas didn’t flinch.

“She belongs to herself.”

The shot rang out. Silas was thrown against the door. Blood spurted from his shoulder.

But before Joseph could fire again, a voice boomed:

“DOWN!”

Sheriff Mather had just arrived, Marabel at his side, snow plastered to her hair.

“Arrest them,” she ordered.

Joseph Quinn paled. His men were disarmed and handcuffed.

Marabel ran to Silas, knelt beside him, and pressed her hand to the wound.

“You won’t die. Do you hear me?” He managed a smile despite the pain.

“I wasn’t counting on it.”

The following spring, the mountains regained their color.

Silas was slowly recovering. Marabel stayed by his side, changing his bandages, speaking to him gently. The girls played outside, their laughter filling the clearing.

They rebuilt the cabin together, enlarged it, and painted it a pale green. They opened their doors to travelers. Soon, the place was called “The Hearth at Granger Ridge.”

Visitors stopped there for a bowl of stew, a warm bed, a smile. Marabel cooked and taught the village children to read. Silas hunted, repaired things, and kept watch.

One summer evening, as the sun set over the valley, Marabel sat beside him on the porch. The girls played in the grass, their hair golden in the sunlight.

She placed a hand on his.

“That fire between us,” she said softly, “it never went out.”

Silas looked at her, his eyes filled with the quiet light of men who have lost everything and found it all again.

“He just needed a place to live,” he replied.

They stayed there for a long time, hand in hand, as the sky turned violet and the first stars pierced the night.

No one, passing over the ridge, could have guessed the whole story. Not the blows, not the snow, not the fear.

But those who stopped saw something else:

the smile of a free woman,

the quiet gaze of a man who had chosen to stay,

and three little girls running in the evening light.

And they understood—without it needing to be said—

that some homes are built not of wood and stone,

but of faith, courage, and love.

A love that had survived the winter,

and that, from now on, would never die.

News

After my wife died, I kicked her son—who wasn’t my biological son—out. Ten years later, the truth came out… and it broke me.

I can still remember the sound of the bag hitting the ground. It was old, torn at the edges—the same…

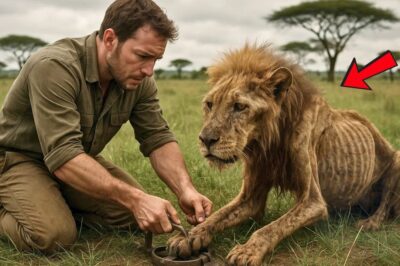

He Freed a Lion from a Deadly Trap — But What the Lion Did Next Shocked Everyone.

He freed a lion from a deadly trap, but what the lion did next shocked everyone. Alex Miller’s hands trembled…

Nobody Could Tame This Wild Police Dog — Then a Little Girl Did Something Shocking!

In the sweltering heat of an isolated ranch, where ochre dust blankets shattered hopes and wooden fences, a deadly tension…

A Roadside Food Seller Fed a Homeless Boy Every Day, One Day, 4 SUVs Pulled Up to Her Shop

Austin’s Secret: How a Street Vendor’s Kindness Sparked the Discovery of a Lost Fortune Abuja, Nigeria. In a world often…

After Working 4 Jobs to Pay her Husband’s Debts, she Overheard Him Brag About His Personal Slave

The Cold Shock: When the Truth Becomes a Stab. It was 11:45 p.m. The silence of the night was broken…

Black Billionaire Girl’s Seat Stolen by White Passenger — Seconds Later, Flight Gets Grounded

The automatic doors opened at Dallas Love Field Airport, letting in the familiar clatter of rolling suitcases and the hurried…

End of content

No more pages to load