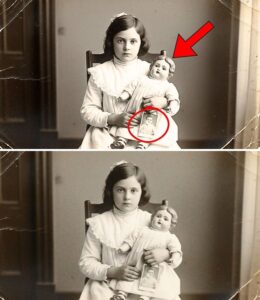

On April 14, 1905, photographer Thomas Wright took a portrait in the parlor of a Boston, Massachusetts home of 7-year-old Mary Parker holding her prized porcelain doll. In the photograph, Mary sits, gently cradling the doll in her arms. Both Mary and the doll wear matching white dresses, a sweet Victorian portrait of a girl and her favorite toy.

The doll had been given to Mary 2 years earlier, in 1903, following the death of her older sister Elizabeth from what the family called “sudden fever.” The doll, which had belonged to Elizabeth, became Mary’s most cherished possession, a link to the sister she lost. For 114 years, the Parker family preserved this photo as a touching memento. A grieving child holding her dead sister’s doll, finding comfort in a toy that kept Elizabeth’s memory alive—until 2019, when antique doll collector Dr. Rebecca Morrison bought the photograph at a Boston estate sale and had it restored using 20,000x magnification.

What Dr. Morrison discovered was horrifying. The doll in Mary’s arms had a small tear in its cloth body, barely visible in the original photograph. But under extreme magnification, something was visible through that tear inside the doll. A tiny, folded photograph, hidden within the doll’s stuffing. When researchers carefully extracted and examined the hidden photograph, they found it showed Elizabeth Parker. But Elizabeth’s face in the hidden photo showed something the family had never mentioned: petechial hemorrhages around her eyes and bruising on her neck. The medical signs of strangulation. Elizabeth had not died of fever. Elizabeth had been suffocated, and someone had hidden her photograph inside a doll, sealing the evidence of a murder inside a child’s toy for 114 years. Subscribe now because this is the story of a photograph that seemed lovable and the Victorian memorial doll that contained evidence of infanticide.

Mary Parker was born on June 3, 1898, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Robert and Sarah Parker. Robert worked as a clerk in a shipping office at Boston Harbor. Sarah worked as a seamstress from home. The family lived in a modest wooden house in the working-class neighborhood of Roxbury, Boston. Mary had an older sister, Elizabeth, born in 1894. The two sisters were close despite their four-year age difference.

Elizabeth was described in family letters as bright, energetic, sometimes willful, a spirited child who could be a challenge for her mother. Sarah Parker’s letters to her own mother in Hartford, Connecticut, preserved in family archives, documented tension between Sarah and Elizabeth. March 1902. “Elizabeth is constantly defying me. She refuses to do her lessons, talks back, disrupts the household. I am at my wits’ end with her behavior.” July 1902. “Elizabeth has become increasingly difficult. Robert says I am too harsh with her, but he does not see her defiance when he is at work. The child exhausts me.” November 1902. “Elizabeth’s behavior is worsening. I have tried discipline, but nothing works. She is 8 years old and should be obedient. I fear she will grow into an uncontrollable woman.”

These letters reveal Sarah’s frustration with Elizabeth’s strong-willed personality, a personality the Victorian-American ethos of child-rearing saw as problematic, especially in girls who were expected to be pliable and obedient.

On March 15, 1903, Elizabeth Parker died suddenly. The death certificate, examined in 2019, listed the cause of death as acute fever of unknown cause. Dr. Henry Morrison, the family physician who signed the death certificate, noted in his records preserved in the Boston Medical Library: “Called to the Parker residence, morning of March 15, 1903. Found Elizabeth Parker, age 9, dead in bed. Mother states: ‘Child had fever during the night and was found unresponsive this morning.’ No obvious signs of illness noted during my previous visits to the family. Cause appears to be sudden fever. Death certificate issued.” The family held a funeral on March 18, 1903. Elizabeth was interred at Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston.

Family letters described the event as devastating, particularly for Mary, who was four and could not comprehend why her sister would not wake up. Following Elizabeth’s death, Sarah Parker gave Mary Elizabeth’s most cherished possession, a porcelain doll with an approximately 15-inch cloth body, wearing a white dress. Sarah told Mary the doll was a special gift from Elizabeth, that Elizabeth wanted Mary to have it, that it would help Mary remember her sister. Mary prized the doll. She carried it everywhere, slept with it, talked to it. The doll became her constant companion and her link to Elizabeth.

In April 1905, 2 years after Elizabeth’s death, the Parker family commissioned a photograph of Mary with the doll. Sarah wished to commemorate Mary’s devotion to her sister’s memory. The photographer, Thomas Wright, came to the Parker home and took the portrait. Mary, 7 years old, sits holding the doll carefully, both wearing white dresses. The photo shows Mary looking earnestly at the camera, holding the doll protectively to her chest. The doll’s porcelain face is visible, with painted features and glass eyes. The doll’s cloth body, dressed in white, appears intact. But inside that cloth body, something was hidden. Something Sarah Parker had placed there two years earlier, shortly after Elizabeth’s death. Something that would remain hidden for 114 years, until modern technology revealed what Victorian-American families had concealed: evidence of a crime that was never investigated.

Elizabeth Parker’s death in 1903, attributed to sudden fever, was not uncommon in turn-of-the-century America. Sudden fever was a common cause of death on children’s death certificates, covering a variety of actual causes, some natural, some not. Victorian-American infant and child mortality was high. Approximately 15 to 20% of children died before the age of five from infectious diseases, malnutrition, accidents, and other causes. Deaths in older children, aged 5 to 12, were less common but still occurred regularly. Physicians had limited diagnostic tools in the early 1900s. If a child died suddenly, particularly if they were found dead in the morning after being put to bed the evening before, doctors often attributed the death to fever, convulsions, or unknown disease, essentially meaning they did not know the cause but had to put something on the death certificate.

This lack of diagnostic precision created opportunities for infanticide and child murder to go undetected. Victorian-American infanticide—the deliberate killing of infants and children—was more common than official records suggested. Historians estimate that many deaths attributed to overlying (accidental suffocation when a parent rolled onto a baby in sleep), sudden illness, or failure to thrive were actually cases of deliberate killing or severe neglect. Motivations for Victorian-American infanticide included: unwanted children, particularly illegitimate births, economic hardship, inability to feed another child, parental mental illness, postpartum depression, psychosis, frustration with difficult children, as Sarah’s letters about Elizabeth suggested, relief from the burden of care.

The most common method used was suffocation, strangling the child with a pillow or by hand, or overlying. This method left minimal physical evidence, especially if the body was not immediately or carefully examined. Signs of suffocation a careful medical examiner might note include: petechial hemorrhages, tiny red or purple spots caused by burst capillaries around the eyes, face, or neck, bruising on the neck or face, bleeding from the nose or mouth, cyanosis, a blue or purple discoloration of the skin. But in 1903, most family physicians did not perform thorough post-mortem examinations, especially on children from working-class families. If a parent said the child had a fever and died in the night, and there were no obvious signs of violence, the doctor typically accepted the explanation and issued the death certificate accordingly.

Prosecution for infanticide was rare. Even when suspected, authorities were reluctant to prosecute mothers. There was sympathy for women struggling with poverty, mental illness, or difficult circumstances. Conviction required clear evidence, which was often impossible to obtain. The result was that many cases of infanticide went undetected and unpunished. Mothers who had killed their children often carried the secret for life, telling family and community the child had died of disease. Sarah Parker’s letters suggest she found Elizabeth difficult and exhausting. The phrase “I am at my wits’ end with her” appears repeatedly. Sarah was caring for two young children while performing piecework sewing from home to supplement the family income. She had little support and no understanding of child development or mental health. Did Sarah’s patience snap one night? Did she suffocate Elizabeth in a moment of rage or desperation? Did she rationalize it as necessary or justified? For 114 years, no one asked these questions. Elizabeth’s death was accepted as natural, a tragic but non-suspicious loss. Until 2019, when a photograph revealed evidence hidden in plain sight, sealed inside a child’s doll, waiting to tell the truth.

The photograph of Mary Parker with Elizabeth’s doll, taken on April 14, 1905, appears, at first glance, a sweet Victorian portrait. Mary sits on a chair, dressed in a white dress with lace trim. She holds the doll carefully in her arms, cradling it to her chest. The doll, about 15 inches tall, has a porcelain head with painted features, rosy cheeks, red lips, glass eyes, and a cloth body dressed in a tiny white gown matching Mary’s. Mary’s expression is earnest but tender. She looks at the camera with the serious face common in Victorian child portraits, but her hands hold the doll gently, lovingly. The photograph captures a moment of childhood devotion. A girl and her beloved toy. For 114 years, the photo was viewed exactly like that, a monument to sisterly love, showing a grieving child finding comfort in her dead sister’s doll.

The photograph passed down through generations of the Parker family. Mary Parker married in 1920, had two children, and died in 1978 at the age of 80. Her daughter kept the photo. Eventually, it ended up at a Boston estate sale in 2019 after Mary’s last surviving descendant died without heirs. Dr. Rebecca Morrison, an antique doll collector and historian based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, bought a box of Victorian photographs and ephemera at the estate sale. Among the items was Mary’s 1905 photo. Dr. Morrison was drawn to it because it featured a particularly fine Victorian doll, the type of collectible doll she specialized in.

Dr. Morrison decided to have the photograph digitally restored to obtain a high-resolution image for her research on doll history. She hired a photo restoration specialist in Boston who scanned the photo at 15,000 dpi. Under high magnification, approximately 20,000%, the restoration specialist noticed something unusual while examining the doll in Mary’s arms. The doll’s cloth body had a small tear, about 5mm long, on the left side near the waist. The tear was barely visible in normal viewing. It looked like a shadow or a fold in the fabric, but under extreme magnification, something was visible through the tear inside the doll: a small piece of paper or cardboard that appeared to be folded several times and flattened, with what looked like printed or photographic images on it. The specialist contacted Dr. Morrison. “There is something inside the doll in your photo. It looks like an image or document may have been stuffed into the body.”

Dr. Morrison was intrigued. Victorian memorial dolls sometimes contained locks of hair from deceased relatives, small notes, or other mementos. But photographs were rare. They were too valuable and fragile to hide inside a toy. Dr. Morrison researched the photo’s provenance. Through the estate sale documentation, she traced it back to Mary Parker, born 1898, died 1978, Boston. She found Mary’s family tree. Sister Elizabeth, born 1894, died 1903, age 9. The doll in the photo had belonged to Elizabeth and had been given to Mary after Elizabeth’s death. And apparently, something had been hidden inside it, something that involved a photograph.

Dr. Morrison contacted the Parker family through genealogical research. She located a distant Parker relative, James Parker, a great-grandnephew of Elizabeth and Mary, living in Newton, Massachusetts, and explained what she had discovered. James was stunned. He had never heard of a photo hidden in a doll. But he agreed to meet Dr. Morrison to discuss the family history. What they uncovered would reveal a crime that had been hidden for 114 years, concealed within a Victorian child’s toy.

After Dr. Rebecca Morrison identified something inside the doll in Mary’s 1905 photo, she worked with James Parker to locate the actual doll. The doll had been passed down through Mary’s family. Upon Mary’s death in 1978, the doll went to her daughter, then to her granddaughter. When the last descendant died in 2018, the doll was donated to a local Boston charity shop, which sold it to a private collector. Through extensive searching, Dr. Morrison located the collector, a woman in Brooklyn, Massachusetts, who had purchased the doll in 2018 and kept it in her Victorian doll collection. Dr. Morrison explained the situation, and the collector agreed to have the doll examined.

In July 2019, Dr. Morrison, James Parker, and textile conservator Dr. Sarah Chen of Harvard University carefully examined the doll. The doll was in reasonable condition for its age of over 115 years. The porcelain head was intact. The cloth body showed signs of wear and age, including the small tear that had been visible in the 1905 photograph. Dr. Chen carefully examined the tear under magnification. Through the opening, she could see layers of cloth and stuffing, and something else. A piece of cardboard or thick paper, folded several times and flattened. With James Parker’s permission, Dr. Chen carefully enlarged the tear just enough to extract the hidden item. Using tweezers, she pulled out a folded piece of cardboard, which when unfolded was approximately 2 inches by 3 inches. It was a photograph, a Victorian Carte de Visite, a small photo mounted on cardboard popular in late 19th and early 20th century America. The photo showed a young girl, aged about 8 or 9, with dark hair, wearing a white dress, seated formally for a portrait. The reverse side read in ink: Elizabeth Parker, Age 9, February 1903. This was Elizabeth, Mary’s sister, the doll’s original owner, photographed one month before her death in March 1903.

But something was wrong with the photo. Elizabeth’s face showed visible marks. Small reddish-purple spots, petechial hemorrhages, around her eyes and upper cheeks. Faint bruising on the left side of her neck. A strained, distressed expression instead of the relaxed face typical of Victorian portraits. Dr. Morrison consulted forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Roberts at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Roberts carefully examined the photograph and concluded: “The marks visible on this child’s face and neck are consistent with strangulation, specifically manual strangulation or smothering. The petechiae are caused by burst capillaries when air supply is cut off. The neck bruising indicates pressure applied to that area. The child’s expression is one of distress rather than calm. This photograph shows a child who has recently been subjected to attempted or actual suffocation.”

But wait, the photograph was from February 1903. Elizabeth died in March 1903. Why would a photograph from one month before her death show signs of strangulation? Dr. Morrison researched further. She found Sarah Parker’s letters in the Massachusetts Historical Society archives. The letters from late 1902 and early 1903 documented Sarah’s growing frustration with Elizabeth. Then, suddenly, after March 1903, Sarah’s letters changed. She wrote of feeling relieved, how peaceful the household had become with only Mary to care for.

The horrifying conclusion: the photo of Elizabeth showing signs of strangulation was taken after Sarah had already harmed her, perhaps an earlier strangulation attempt that Elizabeth survived. One month later, in March 1903, Sarah succeeded. And Sarah, perhaps out of guilt or to document what she had done, placed Elizabeth’s photo inside Elizabeth’s doll and gave the doll to Mary, hiding the evidence of what she had done inside a child’s toy.

Following the discovery of the hidden photograph showing signs of strangulation, researchers reconstructed what likely happened to Elizabeth Parker in early 1903. The timeline:

February 1903. Elizabeth was photographed. The photo shows petechiae and neck bruising consistent with recent strangulation. This suggests Sarah Parker attempted to strangle or suffocate Elizabeth, but Elizabeth survived. Perhaps Sarah stopped, or someone interrupted her, or Elizabeth fought back successfully. Following this incident, Sarah had the photograph taken, perhaps as documentation, perhaps as a memorial in case she intended to try again, perhaps as evidence she could claim showed Elizabeth was ill, if anyone questioned the marks on Elizabeth’s body.

March 1–14, 1903. Elizabeth continued living at home. Sarah’s letters from this period are sparse, but the tone is grim. “The situation with Elizabeth remains intolerable. I see no resolution except through divine intervention.”

March 15, 1903. Elizabeth died. Official cause: Sudden fever. Reality: Sarah Parker suffocated Elizabeth during the night, likely with a pillow, waited until Elizabeth stopped breathing, and then called the doctor in the morning, claiming Elizabeth died of fever. Dr. Henry Morrison, the family physician, examined Elizabeth’s body but did not notice or report any suspicious signs. Either the marks from the February incident had faded, or Dr. Morrison did not look carefully, or he saw them but chose not to question a grieving mother’s statement. Elizabeth was quickly buried, which was customary in 1903. No autopsy was performed. The death was registered as natural.

March/April 1903. Sarah took Elizabeth’s doll, inserted the February photograph through a small opening in the doll’s cloth body, sewed it shut, and gave the doll to Mary. Sarah told Mary the doll was a special gift from Elizabeth, a way to remember her sister. Why did Sarah hide the photo in the doll? Possible reasons: 1. Guilt. She could not destroy the photo but could not display it either. 2. Documentation. Keeping evidence of what she had done, perhaps for a confession or as insurance. 3. Remembrance. Keeping Elizabeth’s image close but hidden. Concealment, hiding the photo where no one would find it and question the marks.

Mary prized the doll for the rest of her childhood and kept it in adulthood. She never knew it contained her sister’s photograph. She never knew the photograph contained evidence of attempted murder. She never knew her mother killed her sister. Sarah Parker died in 1934 at the age of 62. Her death certificate listed the cause of death as heart disease. She never confessed to killing Elizabeth. Letters written in her final years show no remorse or admissions. Robert Parker, Sarah’s husband, died in 1928. There is no evidence he ever suspected Sarah killed Elizabeth. His letters following Elizabeth’s death describe grief but not suspicion. Mary Parker lived until 1978. She kept the doll her entire life, treasuring it as her link to Elizabeth. In old age, she told her daughter: “That was your Aunt Elizabeth’s doll. She died when I was very small. Having her doll made me feel close to her.” Mary died without knowing the doll contained evidence of a murder.

The truth remained hidden for 114 years, sealed inside a child’s toy, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see what Victorian-American families had buried: that sudden fever sometimes meant something much darker, that some deaths were not natural, and that evidence of infanticide could be hidden in the most innocent of places—inside a doll lovingly held by an unsuspecting child.

Following the discovery of the hidden photograph and the conclusion that Elizabeth Parker was likely murdered by her mother Sarah in 1903, Dr. Rebecca Morrison faced a question: What to do with this information? Elizabeth died 116 years ago. Sarah died 85 years ago. Everyone directly involved was long dead. There could be no prosecution, no justice in a legal sense. But there were living descendants, James Parker and others, who deserved to know the truth about their family history.

Dr. Morrison contacted James Parker in August 2019 with her findings. James was shocked, but after reviewing the evidence, he accepted the conclusion. “It’s horrifying,” James said, “but it explains things we never understood. Why my family didn’t talk much about Elizabeth’s death. Why there were so few records. Why the family seemed to have gaps in the early 1900s. They were hiding something. Or someone was.”

Dr. Morrison published her findings in the Journal of American History in October 2019. The article, titled “Hidden Evidence: Victorian-American Memorial Dolls and the Concealment of Infanticide,” used the Elizabeth Parker case, with James’s permission, as an example of how Victorian-American families concealed child deaths, how diagnostic limitations allowed suspicious deaths to go uninvestigated, and how physical evidence could remain hidden for over a century. The article included the 1905 photo of Mary with the doll, enhanced images showing the tear and the hidden photo, the extracted photo of Elizabeth showing strangulation marks, Sarah Parker’s letters documenting her frustration with Elizabeth, the medical analysis of the petechiae and bruising, and historical context on Victorian-American infanticide.

The story garnered media attention. PBS produced a short documentary. The Boston Globe ran an article. “The Doll That Hid a Murder: Victorian Child’s Toy Contained Evidence of Infanticide for 114 Years.” The story resonated because it illuminated several dark truths. 1. Victorian-American child deaths were often uninvestigated. 2. Mothers struggling with difficult circumstances sometimes killed their children. 3. Doctors often accepted parental explanations without scrutiny. 4. Evidence of crimes could remain hidden across generations. 5. Family secrets could persist through silence and concealment.

Morrison worked with the Boston Historical Societies to establish a memorial for Elizabeth Parker. In March 2020, 117 years after Elizabeth’s death, a small memorial service was held at Forest Hills Cemetery where Elizabeth is buried. James Parker spoke. “Elizabeth Parker was 9 years old when she died. For 117 years, we believed she died of a natural illness. Now we know she was murdered by her own mother. We cannot change that. We cannot prosecute anyone. But we can acknowledge Elizabeth’s life and death honestly. Elizabeth was a spirited, strong-willed child who frustrated her mother. She deserved better than she got. She deserved to grow up. She deserved justice. We cannot give her justice, but we can give her truth and remembrance.”

A new plaque was placed on Elizabeth’s grave. Elizabeth Parker, 1894–1903, Died at Age 9. For 117 years, her death was attributed to sudden fever. Modern analysis revealed she was murdered. Her photograph, hidden for 114 years in a doll, bore witness to what was concealed. May her memory honor all children failed by those who should have protected them.

The doll is now housed at the Boston Children’s Museum, displayed alongside the photo of Mary holding it and the hidden photograph of Elizabeth. The exhibit is titled “Hidden Evidence: Victorian-American Childhood and Concealed Crime.” Sometimes, what appears lovable in a photograph conceals horror. Sometimes, a child’s toy contains evidence of a murder. Sometimes, the truth hides in innocent objects across generations, waiting for technology or chance to reveal what families have buried. And sometimes, a Victorian memorial doll, given as a token of remembrance from mother to daughter, was actually a repository for guilt, evidence, and secrets too dark to speak aloud.

Elizabeth Parker died at age nine, killed by her mother, buried as a victim of fever, forgotten for 117 years. A hidden photograph in a doll finally told the truth. Sometimes, justice is impossible, but truth eventually emerges, even 114 years later, even from inside a child’s toy. Elizabeth Parker’s memorial and the exhibit of the Victorian memorial doll are located at the Boston Children’s Museum.

News

The widow bought a young slave for 17 cents. She had no idea who she had once been married to.

The widow, lonely and lost after her husband’s death, bought the young man almost impulsively, without suspecting the story he…

The landowner gave his obese daughter to the slave… Nobody suspected what he would do to her.

The Fazenda São Jerônimo stretched across hectares of coffee and sugarcane, red earth clinging to the boots, a humid heat…

German general captured in 1945… What the Americans did next changed Germany forever.

A German general stands in a field in Maryland. His Iron Cross glints in the spring light. American soldiers watch…

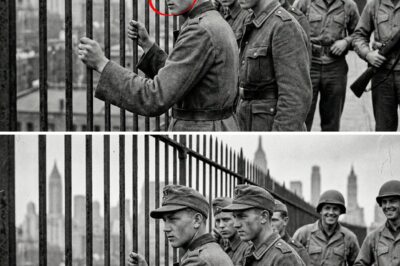

What did the USA do with the child prisoners in 1944? The story of this German boy will shock you.

A 12-year-old boy stands on a pier in New York Harbor. His hands are trembling. A woman in white approaches…

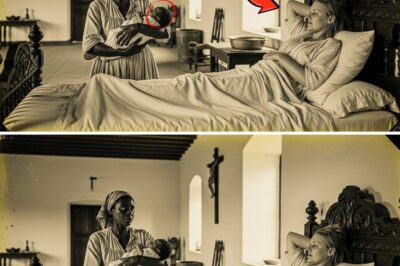

Ana Belén: THE SLAVE who witnessed the birth of the child whose skin revealed the hidden betrayal

In the summer of 1787, when the air in the Valley of Oaxaca burned like a living ember and the…

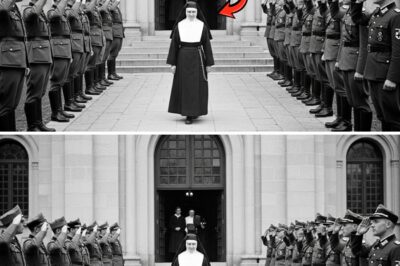

She murdered 52 Nazis with a hollow Bible – the deadliest nun of World War II

An excavated Bible rests on a wooden table. The pages are cut out. Inside, a German Luger pistol and three…

End of content

No more pages to load