The widow, lonely and lost after her husband’s death, bought the young man almost impulsively, without suspecting the story he carried with him. He had arrived at the farm silent, marked by a past no one could decipher. But when she found a hidden locket in his pocket, the truth exploded like a revelation. The photograph showed a white woman in an expensive dress, a wedding ring on her finger.

Dona Helena Vasconcelos never thought she would buy anyone. Not like this, not under these circumstances. She was 42 years old, widowed for three months, and the coffee plantation in the interior of Minas Gerais was bleeding debt like an open wound. Her husband, Coronel Augusto, had died of yellow fever, leaving behind more debts than assets.

Creditors knocked on the door every week. The field workers threatened to leave if they were not paid. That morning in August 1884, she went to the auction in the town square without knowing exactly why. Perhaps it was the loneliness. Perhaps it was because the Big House echoed too empty since Augusto left. Perhaps it was the need to feel she still had control over something, anything, even if it was just the illusion of a decision.

The auction took place in front of the main church. Men with top hats and canes walked around, examining the human merchandise as if inspecting cattle. The auctioneer, Senhor Tavares, a gaunt man with a waxed mustache, shouted the bids while sweat ran down his greasy temples. The August sun punished relentlessly. The smell of piled bodies, mixed with dust and cigar smoke, formed a suffocating cloud.

Helena stopped in the shade of a fig tree, watching. She didn’t want to be seen. She didn’t want the neighbors commenting that Coronel Augusto’s widow was in that place, but something held her. A morbid curiosity, a need to understand that world she had always been close to but never truly belonged to.

Then she saw him. The young man could not be more than 25, tall, broad-shouldered, dark skin glistening in the sun, but what drew attention were his eyes. He didn’t look down like the others. He didn’t have that stooped posture of one who has already accepted defeat. He looked fixedly ahead, as if he were in another place, as if all this were merely temporary.

Before I continue this story that will turn your head upside down, I must ask you for something important. If you enjoy this true narrative and want to see more stories like it, subscribe to the channel now and let me know in the comments which city or state you are watching me from. That helps the channel grow a lot and bring more content like this. And stay until the end, because the outcome of this story will pull the rug out from under you.

The auction for the young man began at 1,000 réis. No one bid. He had welts on his back, visible through the torn shirt. Signs of the lash, signs of trouble. No one wanted a problematic enslaved person. Tavares dropped to 30,000 réis. Silence. He dropped to 10. A fat farmer bid 5,000 réis, more for fun than genuine interest. Another bid six. The fat man raised it to seven, and then Helena heard her own voice: “17 centavos of réis.” It was a ridiculous, insulting bid, but no one topped it. The fat farmer laughed loudly and said she could keep the trash. Tavares banged the hammer. Deal done.

Helena paid immediately in coins she pulled from her velvet purse, 17 centavos, the price of a kilo of sugar, the price of two tallow candles. The young man was brought to her. Tavares handed over the papers. Name: Miguel. Age: 24 years. Origin: Fazenda Santa Eulalha, Vassouras, Rio de Janeiro. Reason for sale: Insubordination.

Helena folded the paper and put it away. She looked at Miguel. He looked back, without fear, without anger. Just that distant look, as if calculating something she could not understand.

They returned to the farm in an old cart pulled by two tired horses. Helena in the front, Miguel in the back. Neither spoke during the entire journey. The silence was thick as molasses. She felt his eyes on her back. It wasn’t threatening, it was just present, constant.

The Vasconcelos Fazenda had seen better days. The Big House, built 40 years earlier, showed signs of neglect, broken tiles, peeling paint. The coffee plantation stretched over the hills, but there was a lack of labor for the harvest. Dona Helena had only six workers left, all old or sick. Augusto had freed some before he left. The others fled afterward. She didn’t have the strength to pursue them.

Miguel was housed in a vacant senzala (slave quarters) in the back of the property. Helena instructed Benedita, the cook, to bring him food. She herself remained in the Big House, sitting in Augusto’s armchair, staring at the closed door of the office where he usually spent nights drinking cognac and complaining about coffee prices.

That night, she couldn’t sleep. She wondered why she had bought Miguel. She didn’t need him. She had no work to give, no money to feed another mouth. But there was something about him, something that both troubled and fascinated her. That look, that posture, as if he carried a secret too heavy to fit inside his body.

The next morning, she went down to the coffee plantation. Miguel was there, working alongside the others, but he worked differently, with precision, with technique. It wasn’t the work of someone who had learned with a hoe, it was the work of someone who understood the land, who knew when to prune, when to harvest, when to let it rest.

Benedita commented at lunch: “That young man is not ordinary, Senhora, he has the manner of someone who has already commanded, who has already owned.” Helena did not reply, but the seed of curiosity was planted. She began to watch him from a distance every day.

Miguel read. She saw him one afternoon sitting under a jabuticaba tree, an old book in his hands. Where had he gotten it? How did he know how to read? Enslaved people did not read. They were not allowed, did not have access.

A week later, she summoned him to the Big House. He entered barefoot, hat in hand. He stopped at the living room door. Helena sat in the armchair, a cup of cold coffee on the side table beside her. “You can read?” she said. It wasn’t a question. “Yes, Senhora.” “Who taught you?” Miguel hesitated. The first sign of weakness she saw in him. “Someone who believed I could learn.”

The answer was evasive. But Helena didn’t press. Not yet. “I need someone who knows how to count. The farm books are a mess. My husband was not good with numbers. Can you calculate?” “Yes.” “Then you will work here in the office, one hour a day after working in the coffee plantation.”

Miguel nodded. He left. Helena remained seated, feeling she had just opened a door she perhaps should not have opened. Days turned into weeks. Miguel worked in the office every afternoon. He organized the ledgers, discovered debts Augusto had hidden, discovered false creditors charging non-existent interest. Helena began to trust him more than she should, more than was safe.

They talked, initially just about the farm, then about other things, books. He had read Machado de Assis, he had read José de Alencar, he had opinions on politics, on the Law of the Free Womb, on the winds of abolition that were blowing stronger and stronger.

“How do you know all this?” she asked one afternoon. “I learned from someone who loved me,” he replied, then closed himself off, as he always did when the conversation approached the past too closely.

It was Benedita who discovered the locket. She was washing Miguel’s clothes when she felt something heavy in the torn pants pocket. “An old silver locket with a fine chain.” She brought it to Helena. “I found this in his things, Senhora. I think you need to see it.”

Helena opened the locket. Inside, a small, faded but still clear photograph. A young white woman, blonde hair pinned up in elaborate braids, an expensive lace dress, the kind that cost a common laborer’s annual salary. And on her finger, a ring, a wedding ring.

Helena’s heart pounded. She turned the photo over. On the back, a delicate inscription: For Miguel, my eternal love. Isabela. 1881.

The world stopped. She summoned Miguel that same evening. He entered the office and saw the locket on the table. His expression did not change, but something in his eyes went out, as if a candle had been extinguished.

“Who is Isabela?” Helena asked. Miguel was silent for so long that she thought he would not answer. Then he sat down without asking permission, sat in the chair across the table like an equal, and began to speak: “Isabela was the daughter of the Baron of Vassouras. I was the son of a maidservant and the farm foreman. I grew up in the senzala, but my father, being who he was, taught me to read. He said knowledge was the only thing no one could take from you. Isabela and I grew up together. She taught me French. I taught her to climb trees. We were children. We did not understand what the world saw when it looked at us. When we grew older, we were still friends. But friendship turned into something else. Something that shouldn’t have a name, shouldn’t exist, but it existed in the glance, in the accidental touch of hands, in the hidden conversations in the garden after everyone was asleep. One day, she told me she loved me. I said she was crazy, that she would ruin herself, that her father would hang me. She said it didn’t matter, true love didn’t ask society for permission.”

Helena listened, without blinking, without truly breathing. “We fled,” Miguel continued. “One night in 1881. She took jewelry. I took nothing but the clothes on my back. We went to Rio de Janeiro. She sold the jewelry. We rented a room in a boarding house in Botafogo. We married in a small church. The priest was an abolitionist, he didn’t care. He performed the ceremony, blessed us. We lived as man and wife for 8 months. The best 8 months of my life. She taught French lessons. I worked as a stevedore at the port. We had nothing. But we had everything. Until the Baron found us. He did not come alone. He brought thugs, the Capitão do Mato (bush captain), the police. They broke down the door in the early hours. Isabela screamed. I tried to defend her. I took a rifle butt to the head. I woke up in chains. The Baron annulled the marriage. He said it was invalid, I was his property, I couldn’t marry. Isabela pleaded, cried, said she would kill herself if they took me. The Baron hit her, in front of everyone, hit his own daughter. They brought me back to Vassouras. They lashed me, 20 lashes, one for each day I was gone. Isabela was locked in her room. I heard she went mad, she didn’t eat, she didn’t talk, she just stared out the window. Three months later, they sold me. The Baron didn’t want me near. He said I was a bad influence. He sold me to a horse trader in Juiz de Fora. From there, I was sold again, and again, and again, until I arrived here, until the Senhora bought me for 17 centavos.”

Silence filled the office like rising water. “Isabela?” Helena asked, her voice raw. “I don’t know. I have no news. I only have this,” he indicated the locket. “It is all that is left of my happy time.”

Helena didn’t know what to say. She had no words for such a burden. She picked up the locket and handed it back to Miguel. “Keep this safe, and do not tell this story to anyone else. If they knew, they would kill you.” He took the locket and left.

That night, Helena stayed awake until dawn, thinking, calculating, feeling something strange growing in her chest. It wasn’t pity, it was rage. Rage at the world that allowed such a thing, rage at the system that crushed true love under the heel of property, rage at herself for being part of it.

The next day, she summoned Miguel again. “I am going to free you. I will make the papers. You will be free.” Miguel looked at her as if he didn’t understand. “Why?” “Because no one should own anyone. And because you have suffered too much.” She expected gratitude, she expected tears. But Miguel just said, “Thank you, Senhora, but I cannot leave. Not yet.” “Why not?” “Because as long as I have hope of finding Isabela, I need to be alive, a roof over my head, food. Here, I have that. Outside, I am just another free Black man in a world that hates free Black men. Here, at least, I know what the danger is.”

Helena understood. Freedom without possibility was not freedom. It was just another kind of prison. “Then do this: you will work here, receive wages, live in the guesthouse, and when you want to leave, you will leave, without papers, without debts, truly free.”

Miguel accepted. The months passed. The farm began to make a profit again. Miguel handled the accounting. Helena handled the sales. They became partners, not friends. Not quite, but something close.

A year later, in May 1885, a letter arrived for Miguel. Sender: Carmelite Convent of Petrópolis. Helena brought it in person. Miguel opened it with trembling hands. He read, his face collapsing. It was from Isabela, or rather, about Isabela, written by a Mother Superior. It said that Isabela had entered the convent six months after the separation, took her vows, lived there in silence and prayer, and had died three weeks earlier. Pneumonia, it was quick. Without suffering. The letter included an enclosure, a letter from Isabela, written years before, asking for it to be delivered to Miguel if she died.

Miguel read it alone. Helena respected the space, but later, he told her. Isabela said she had never stopped loving him, she had taken the vows because the world did not allow her to belong to him. So, she would belong to God, she prayed for him every night, she hoped they would meet in a place where skin didn’t matter, where love was just love.

Miguel kept the letter with the locket. He did not cry, at least not in front of Helena, but something in him changed, as if the last chain had been broken. Three months later, he left. Helena offered him money. He refused. He said he had enough from his wages. He said he would go north, he had heard of lands where men like him could start anew. They said goodbye at the farm gate. Helena held out her hand. Miguel shook it firmly, as an equal. “Thank you for seeing me as a person,” he said. “Thank you for teaching me that people have no price, not even 17 centavos.” He smiled, turned, and left.

Helena never saw him again, but she never forgot him either. She never forgot the man who loved so deeply that even the hell of slavery could not extinguish that flame. She never forgot Isabela, who chose God because she was not allowed to choose Miguel. She never forgot that she bought a man for 17 centavos and discovered that within him resided a story worth more than all the gold in the world.

Years later, when abolition finally came in 1888, Helena freed everyone who remained, sold the farm, moved to the capital, used the money to fund schools for former enslaved people, and never remarried. She kept Miguel’s purchase receipt, 17 centavos. She nailed it to the office wall. Below it, she wrote a phrase: The Price of Shame. And every time someone asked what that meant, she told the story. The story of the man who loved an impossible woman, who was bought for less than a kilo of sugar, who proved that true love does not ask society for permission, does not bend before unjust laws, and does not die even when lovers are separated by the brutal violence of human cruelty. Because, in the end, Helena understood something that changed her forever. It does not matter how much you pay for someone, you never truly own a human being, especially those whose souls are too free to fit into chains. And that truth, when finally understood, leaves everyone speechless.

News

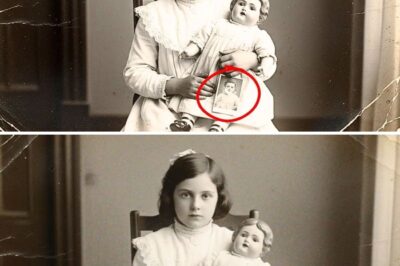

This photograph from 1905, showing a girl with a toy, seemed harmless – until restoration revealed something sinister.

On April 14, 1905, photographer Thomas Wright took a portrait in the parlor of a Boston, Massachusetts home of 7-year-old…

The landowner gave his obese daughter to the slave… Nobody suspected what he would do to her.

The Fazenda São Jerônimo stretched across hectares of coffee and sugarcane, red earth clinging to the boots, a humid heat…

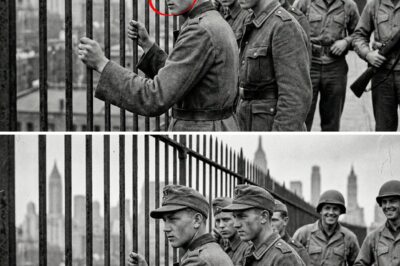

German general captured in 1945… What the Americans did next changed Germany forever.

A German general stands in a field in Maryland. His Iron Cross glints in the spring light. American soldiers watch…

What did the USA do with the child prisoners in 1944? The story of this German boy will shock you.

A 12-year-old boy stands on a pier in New York Harbor. His hands are trembling. A woman in white approaches…

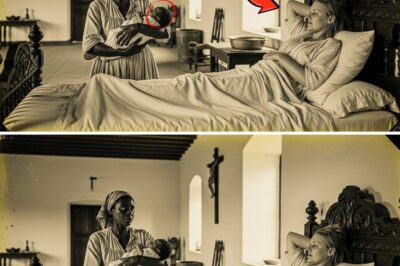

Ana Belén: THE SLAVE who witnessed the birth of the child whose skin revealed the hidden betrayal

In the summer of 1787, when the air in the Valley of Oaxaca burned like a living ember and the…

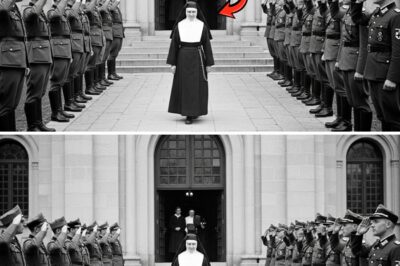

She murdered 52 Nazis with a hollow Bible – the deadliest nun of World War II

An excavated Bible rests on a wooden table. The pages are cut out. Inside, a German Luger pistol and three…

End of content

No more pages to load