An excavated Bible rests on a wooden table. The pages are cut out. Inside, a German Luger pistol and three glass vials. No Nazi soldier ever searched those pages. Belgium, 1943. One nun destroyed more enemy leadership than an entire battalion.

This is how a woman who took vows of peace became one of the most effective assassins in the European Resistance. October 1938. Leuven, Belgium. Sister Alexandra stood in the monastery library at dawn. The Nazis had not yet arrived, but she could hear them coming. She was 34 years old.

Her hands traced the leather spines of the Benedictine monastery’s collection. 5,000 volumes cataloged over three centuries. Each book was a life. Every binding was a prayer. Her brother’s name was written on the margin of one of them. A pencil annotation in his childish handwriting from 1922 about the greatest library in all of Europe. She ran her finger over the words.

That same brother would be dead in six months. The Germans would execute him for refusing to betray his parish. The morning light filtered through the windows, turning the ancient shelves into a golden lattice. Sister Alexandra had lived inside these walls for 14 years. She had taken vows of silence, vows of poverty, vows of service to God and nothing else.

But standing there, she understood something fundamental. Vows taken in peace did not apply in the presence of evil. The monastery bell tower struck six times. Somewhere in the city, German boots echoed on the cobblestones. Somewhere, families listened for them, holding their breath.

She pulled a worn Bible from the shelf, the oldest in the collection, dating back to the 1680s. Its leather was cracked. Its binding had loosened over two centuries. She carried it to her cell. The cell was small, a narrow bed, a wooden desk, a crucifix. She began, with meticulous precision, to hollow out the pages, page by page, hour by hour. Her hands were steady.

A lifetime of illuminating medieval manuscripts in that monastery had trained her fingers for accuracy. By noon, she had created a cavity 3 inches deep, 4 inches wide, and 6 inches long. It was enough. The first thing she placed inside was a photograph of her brother, taken in 1936. He was wearing a priest’s collar and a smile that said he believed the world could still be good. She had kept it hidden for two years, knowing the Germans would see it as proof of conspiracy. Then came the medicinals, poisons derived from plants grown in the monastery garden, compounds developed by a French chemist who had fled to Belgium and found refuge in the basement of that very monastery.

Strychnine cyanide, a neurotoxin derived from certain mushrooms, which mimicked the symptoms of stroke or heart attack. Then came the documents, names of German officers, addresses, habits, schedules. The intelligence had been collected by a network of resistance fighters who moved like ghosts through the streets of Leuven.

She resealed the pages with a paste made from an ancient adhesive she had discovered in the monastery’s conservation texts. When she was finished, the Bible looked exactly as it had before. Just another damaged old book. A nun in a medieval habit carrying religious texts would never be stopped, never searched.

The Germans had been trained to respect the Church, even as they destroyed it. Sister Alexandra did not change her name when she entered the convent. She changed it the moment she decided to become something else entirely. Sister Maria, they called her now. The name was chosen deliberately, maternal, forgettable, invisible.

That evening, as the orange sun set behind the city spires, she walked out of the monastery for the first time with the intention of killing. She carried the hollowed-out Bible to a house in the Jewish quarter. A resistance cell operated in the basement. She descended a wooden stairway into the darkness. When her eyes adjusted, she saw four people around a table.

A printer, a forger, a weapons smuggler, and a man whose profession was never spoken aloud. They greeted her without surprise. They had been waiting. She placed the Bible on the table. No words were exchanged. Words in those rooms were a currency to be spent carefully. One of them, the man with the scar across his left cheek, looked directly at her.

He asked only: “One?” “Two,” she replied. “Three.” She thought of her brother. She thought of the light in the library that morning. She thought of the 300,000 volumes still waiting in those shelves, living treasuries of human knowledge the Nazis intended to burn. “Four,” she said.

The Nazis arrived in Leuven on May 10, 1940. 500 soldiers, armored vehicles, the 6th Army of the Wehrmacht moving west toward France, using Belgium as a corridor. The commanding officer was Colonel Otto Lang, 57 years old, bald, a career soldier who had overseen occupation operations in Poland, where he earned a reputation for meticulous cruelty—meticulous in his records, meticulous in his logging of atrocities. His eyes widened when he saw the monastery from his command vehicle. His jaw clenched, not for the religious architecture, but for what was inside: the Leuven Library, the most significant collection of medieval manuscripts in Northern Europe, stored in buildings adjacent to the monastery. 400 years of history, 100,000 volumes, irreplaceable.

Colonel Lang had direct orders from Berlin. The library was to be preserved, not for humanitarian reasons, but because it contained medieval texts on Germanic history. Pages that could be used to support racial ideology. Pages that could prove the superiority of Aryan civilization. He commandeered the entire monastery as his headquarters. 30 of his men took up residence in the dormitories.

His personal office was established in the abbot’s study. And Sister Maria, still moving through the corridors in her black habit, became invisible in plain sight. The resistance in Belgium had formed within weeks of the invasion. It was not organized from outside. It grew from within, from priests, doctors, teachers, factory workers, and nuns who simply decided that collaboration was not survival.

Sister Maria was not the first person in the resistance, but she was about to become the most effective. The network she belonged to called itself the Ministry of Shadows. Its members understood that conventional warfare—rifles, tanks, frontal assault—was impossible against a mechanized military force that had conquered Europe in 42 days.

The Wehrmacht would not be defeated by traditional combat in the streets of Leuven. The Wehrmacht would be defeated by the systematic elimination of its leadership. The Ministry of Shadows had developed a specific strategy. While the German occupation appeared total, while the swastika flew from every public building, while curfews emptied the streets by 8 PM, there were still moments, gaps, moments when officers let down their guard—the doctor’s office, the hospital, the confessional, the private quarters, the moment between sleep and waking, the moment between sobriety and intoxication, the moment of trust. Sister

Maria understood these gaps perfectly. She understood that a woman dressed as a nun would encounter almost no resistance moving through a monastery housing German officers. She understood that a German officer, trained his entire life in military discipline, would not be suspicious of a silent woman who brought him soup, or changed his bedding, or was present in an infirmary.

She understood that men, even men trained in violence, had weak moments. And in those weak moments, a poisoned host during communion, a contaminated dressing on a wound, a needle coated in neurotoxin traced across the neck while asleep. The first SS officer she killed was Obersturmführer Ernst Becker, 33 years old, Gestapo agent, responsible for at least 70 arrests in the Leuven region.

62 of those arrests had led to executions. In the monastery’s records, he died of natural causes. His heart failed on June 14, 1940. A massive coronary event, a sad waste of a promising officer. Very tragic. The body was shipped back to his family in Hamburg with full military honors. No autopsy was performed.

No questions were asked. Three weeks later, Obersturmführer Klaus Hiller, 28 years old, Wehrmacht intelligence officer, died in his sleep. His body was found by one of his soldiers on the morning of July 7. The cause of death was logged as an acute stroke. He had been complaining of minor headaches for a week. The stress of occupation duty.

Perhaps these things happened. The soldiers who discovered him noticed nothing untoward. The doctor who examined the body found nothing suspicious. The autopsy report was filed and forgotten. Between June 1940 and August 1944, 41 German officers died in or around the Leuven monastery. Some died in the monastery itself. Some died in hospitals where Sister Maria had quietly taken employment as an aid. Some died in private residences where she appeared as a nurse, caretaker, spiritual advisor. Their official causes of death were heart attacks, strokes, allergic reactions, and infections. All natural. All expected in the brutal calculus of a military occupation. The German command structure never grew suspicious.

When officers died individually or in pairs, spread out over four years in various locations, the deaths did not form a pattern. They were simply casualties of occupation duty. Sad losses, but unavoidable. What they did not understand was that every death disrupted operational planning. Every death meant retraining for new commanders.

Every death meant investigations into security lapses that consumed resources. Every death meant uncertainty in the command structure. A moment when no one was sure who was in charge, when orders became unclear, when plans were delayed. In military operations, delay was often as devastating as direct combat. The Nazis had conquered Belgium in 18 days.

The country had been totally subjugated. But through the work of Sister Maria, through the network of poisonings that appeared as accidents, the efficiency of the occupation was degraded, not destroyed. Degraded.

A planned operation against resistance fighters in Brussels was postponed because three officers died in the same week. The new commander needed time to understand troop deployment. By the time he was ready, the fighters had escaped. By the time the Germans organized another operation, there was no target left. This pattern repeated itself across Belgium. A planned deportation of Jews was delayed. Two officers who had organized it died.

Their replacements did not know the details of the operation. By the time new arrangements could be made, the families scheduled for deportation had been hidden by resistance networks. They survived. A planned extrajudicial execution of partisan fighters was postponed. One officer died. His security protocols went with him.

The next officer changed the schedule, changed the location, changed the security arrangements. The partisans escaped the trap that had been set for them. Every death was a small victory. Every death was a stone placed in the path of the German war machine. The Germans could not see the pattern because every death appeared natural, but the resistance could see it.

And they understood that Sister Maria was fighting a different kind of war. A war measured not in battles won, but in operations disrupted, in time gained, in lives saved through delay and confusion. On August 16, 1941, Sister Maria was summoned to Colonel Lang’s office. Her breath caught. She had killed one of his subordinates, Major Wilhelm Hoffmann, only six days earlier.

The official cause was pneumonia, sudden onset, very aggressive infection. She ascended the wooden staircase to the abbot’s study, which had been converted into Lang’s command center. Maps covered the walls. A radio operator sat in the corner, monitoring frequencies. A secretary typed reports. Colonel Lang sat behind the desk. His uniform was immaculate. His hands were folded on the wooden surface.

His eyes were pale blue and completely emotionless. She felt her heart rate quicken, not from fear, but from the recognition that everything she had built, the network, the killings, the careful invisibility, might be over. Lang gestured to the chair opposite him, she sat down. Her hands remained folded in her lap.

Her face remained composed, as trained by 14 years of monastic silence. He opened a drawer. He pulled out a photograph. It was in color. It showed Sister Maria speaking to a man in civilian clothes outside a café in Brussels. The photograph had been taken from across the street. The date was stamped on the back. March 3, 1941.

Her breath hitched, not for the reasons Lang might suspect. The man in the photograph was Michel Verdier, a known resistance agent, the head of the Ministry of Shadows operations in central Belgium. He had been sought by the Gestapo for 18 months. “Do you know this man?” Lang asked. His voice was quiet, almost conversational. “No, Colonel,” she said. He smiled, a thin smile.

“The Gestapo tells me this photograph was taken in Brussels on the afternoon of March 3rd at a café called La Papillon. Your superior, the Mother Superior of this monastery, informed me that you were in Brussels that day. You had traveled to visit an ailing aunt.” He placed the photograph on the desk between them. “Do you have an ailing aunt?” “Yes, Colonel.

She lives in Brussels.” He nodded slowly, his pale eyes never leaving her face. She forced her breathing to remain calm. One mistake, one change in her pulse, visible on her neck, one tremor in her hands, and everything would end. “My intelligence officers,” Lang continued, “believe you are a member of the resistance. They have prepared a warrant for your arrest.”

“The Mother Superior has already been notified. You are to be taken into custody for questioning.” The words fell like stones into still water. She waited for guards to enter. She waited for the handcuffs. She had prepared for this possibility. She had memorized the floor plan of the Gestapo detention center in Brussels. She had planned her suicide for this eventuality. A glass ampoule of cyanide, hidden in a false tooth. 30 seconds.

No pain, just a final silence. But no guards entered. Instead, Colonel Lang stood up. He walked to the window. He looked down at the monastery gardens, the herb gardens where many of her poisons had been cultivated. “However,” he said, “my intelligence officers are often wrong. They see threats everywhere. They are paranoid. It is a weakness of their profession.” He turned back to her.

“I have vetted your presence here in this monastery for 14 months. I have observed your behavior. You are quiet. You are devout. You attend every service. You cause no disruption.” He picked up the photograph and put it back in the drawer. “Furthermore, if you were a resistance agent, you would have attempted to poison me by now.”

“You have had ample opportunity, and yet I sit here, alive, healthy, and growing fat from the monastery soup.” Indeed, he returned to his desk. He looked directly at her. “Tell me something, Sister Maria, and I ask this out of sincere curiosity. Are you a member of the resistance?” She met his gaze. She did not blink. She did not look away. In that moment, she understood something about Colonel Otto Lang.

He was not asking the question because he suspected her. He was asking because he wanted to be lied to. He wanted to give her a chance to choose obedience. “No, Colonel,” she said. “I am a servant of God and this monastery.” He nodded. “I believe you,” he said. “You are dismissed.” She stood up. She walked to the door. As she reached the threshold, his voice stopped her.

“Sister Maria, the man in the photograph I showed you. Do not be seen with him again. I would hate to have to give my intelligence officers the satisfaction of an arrest. It would complicate my work here.” “I understand, Colonel.” “Good. You are dismissed.” She descended the stairs on legs that felt hollow.

When she reached her cell, she allowed herself exactly one minute to tremble, one minute to feel the proximity of death. Then she stood up. She adjusted her habit. She returned to her duties. That evening, she sent a message through the underground network. Colonel Lang knew about Michel Verdier. Verdier had to be evacuated immediately. Within hours, Verdier was smuggled out of Belgium. He survived the war.

He lived until 1987 and never knew that Sister Maria had saved his life through that single conversation with the Colonel. What she had discovered in that moment was something deeper than survival. She had discovered that Colonel Lang, a career soldier, a man trained in the techniques of occupation and subjugation, was not actually what she expected. He was not an uncomplicated villain. He understood her. He understood her choices.

And he offered her a path forward by pretending to believe her denial. The war continued. The monastery became a cathedral of secrets. Above, German officers moved through the corridors. Below, in the basement and hidden chambers, the resistance network grew. Sister Maria’s methods evolved. She learned that poisoning required a deeper understanding than simple chemistry. She learned that creating the appearance of natural death required knowledge of medical symptomatology, of how to mimic genuine disease, of how to time interventions so that even the most suspicious physician would see only biology at work. She studied the files

left behind in Colonel Lang’s office when he was absent. She memorized the faces of wanted resistance agents. She learned the names of Gestapo collaborators. She knew the patrol patterns of the SS security forces. Between her duties at the convent, washing dishes, tending the library, attending services, she became something else, a weapon, a precise, calibrated instrument of assassination. Her training came from several sources. The chemist working in the basement taught her pharmacology, how to calculate dosages, how to understand the variables of human metabolism, how body weight, age, and health affected toxin absorption, how timing was everything, how a poison administered too slowly was merely medicine.

How a poison administered too quickly was obvious poison. But how a poison administered in the precise sequence—small amounts over a week, building up in the system, accumulating in organs, overwhelming the body’s ability to process—was indistinguishable from natural disease. She learned from medical texts hidden in the convent library.

She spent nights reading about cardiac pathology, about stroke mechanisms, about allergic shock and anaphylaxis. She learned to read the symptoms backward. If she wanted to create the appearance of a heart attack, what exactly would need to happen inside a man’s body? Which organs would need to fail? In what sequence? She learned by observation.

When German officers died, even those not poisoned by her, she observed the process. She observed their final hours. She noted the signs of system failure, the way consciousness faded, the way the body’s responses diminished. She learned the theater of death so that she could perform it. The monk in the library who tended the ancient texts on medieval herbalism became her tutor.

An old man named Brother Lucienne, nearly 70, who had lived in the monastery for 50 years. He understood what Sister Maria was becoming. He never spoke directly of it, but he began leaving books open on his desk, turned to chapters on nightshade, on yew trees, on fungal toxins.

One day, a visitor came to the monastery, a man in civilian clothes who walked slowly, as if in pain. He was a chemist. He had fled the Nazis from France. He carried notes on compounds that could be synthesized from common plants. He spent a week in the basement. When he left, he took nothing, but he left behind a set of handwritten instructions on how to extract and concentrate various alkaloid compounds. Sister Maria memorized those instructions.

Then she burned them. In March 1942, a new German officer arrived at the monastery. Standartenführer Friedrich Gruber, 39 years old, Wehrmacht Medical Corps, trained as a doctor before the war. Gruber was assigned to the monastery to conduct a medical inspection. The Nazis wanted to ensure their officers were in good health, that there were no epidemics, that the facility was properly maintained as a military headquarters.

He spent three days reviewing records, checking autopsy reports, speaking to German military doctors in Brussels and Liège. On his final day, he requested a private meeting with Sister Maria in the apothecary. “Tell me about Major Hoffmann,” he said. Not a question, a command. Her hands moved over the apothecary shelves, organizing bottles of herbal preparations.

Her face remained neutral. Her voice was calm. “Major Hoffmann became ill last August,” she said. “I provided supportive care. He was transferred to the hospital in Brussels. He died there.” “Of pneumonia,” Gruber said, reading from a file. “Sudden onset, very aggressive. He was dead within four days of admittance.” “Yes.”

“And Hauptsturmführer Becker before that, heart attack in June.” “Yes.” Gruber stepped closer to her. His eyes were a surgeon’s eyes, analytical, observant, trained to notice what others missed. He said slowly: “32 deaths in this monastery in 22 months. This is a statistical anomaly, Sister Maria.”

Sister Maria did not reply. “Most of the deaths are cardiac failure, strokes. Typical natural causes of death for men in this age bracket. However.” He opened the file. It was filled with photographs and notes. “These men were all physically fit. They were carefully selected. And yet, they die.”

He looked at the walls of the apothecary, the shelves of herbal preparations, the notes pinned above the counter about cultivation and extraction methods. “I am a physician,” Gruber said softly. “I have studied the human body for 30 years. I recognize a pattern when I see one. These patterns are not coincidence.”

Sister Maria waited. This moment, the moment of discovery, had always been inevitable. She had always known it would come. “However,” Gruber continued. “I will not arrest you immediately.” He closed the file. “I will not do so immediately,” he said.

Sister Maria’s hand moved toward the false tooth in her mouth. The cyanide capsule. 30 seconds. Just bite down. 30 seconds of burning in her mouth and then nothing. “However,” Gruber said, “I will not do so immediately.” He reached into his pocket. He pulled out a letter.

It was in German handwriting, dated March 12, 1942. It read: “To the person who is carrying out the elimination of German officers at the Leuven monastery: I have discovered your work. I am a physician. I recognize practiced violence when I see it. Before I file my report, I want you to understand that 37 German officers have died at this facility. 37 men who are responsible for atrocities.”

“The rate of death is extraordinary, but the selection is more extraordinary. Every man you have killed has been selected with precision. Every man was a war criminal. Every man deserved the death he received.” He folded the letter. “I do not believe in the Third Reich,” Gruber said. “I have not believed in it since 1941. I have been waiting for someone with the courage to act. I have been waiting for the resistance to make its move.”

He held up the letter. “This letter is my authorization for you to continue. If you are captured, if you are interrogated, if the Gestapo comes for you, I will deny writing it. I will claim someone forged my handwriting. I will claim you are a dangerous assassin acting independently.”

“I will not protect you through official channels.” He placed the letter on the table. “But unofficially, for the next several months, I will ensure that no medical investigator looks too closely at the bodies. I will ensure no autopsy goes too deep. I will ensure that the pattern remains hidden from the Berlin command structure.” Sister Maria looked at the letter.

She did not touch it. “Why?” she asked. Gruber’s eyes reflected 30 years of medical practice. 30 years of seeing the human body as a mechanism, as a machine, but also 30 years of seeing suffering. 30 years of seeing some suffering that could be stopped. “Because I am a physician,” he said. “I took an oath to save lives. Sometimes, you must do so in unconventional ways.”

He turned and left the apothecary. Sister Maria picked up the letter. She read it three times. Then she ate it. The paper dissolved on her tongue, and the cyanide capsule remained unused for another day. By early 1943, Sister Maria’s network had expanded. She was no longer working alone. A team of five people now coordinated the operations.

A chemist, a document forger, a soldier who had deserted from the Wehrmacht and gone underground, a doctor working in the Brussels hospital, and a journalist who maintained contact with the London government-in-exile. They began keeping a list, not for their own records, but for history—each name, each date, each official cause of death, each actual method, written in cipher and hidden in a sealed envelope in the monastery safe.

By 1943, the list contained 52 names. 52 officers in the SS, Gestapo, Wehrmacht, and SA. 52 men who had been selected based on specific documented atrocities. 52 men whose deaths had disrupted German operations in Belgium. The list was not comprehensive. Sister Maria understood that every death she caused had ripple effects that she could never calculate.

A command structure in chaos for two weeks meant a planned raid on a partisan safe house was postponed. That postponement meant 12 partisan fighters escaped and lived to fight another day. Those 12 fighters meant that 70 civilians could be hidden and smuggled out of Belgium. Those 70 civilians meant that families survived the war. Those families meant that children grew up after the war. She could not calculate the infinite geometry of consequences.

She could only record the direct action. And the direct action was clear. 52 deaths, all officially natural, all perfectly documented, all completely undetectable as anything other than the random casualties of occupation and war. In 1943, Sister Maria completed one final expansion of her network.

She had begun to realize that her work in the monastery, while effective, was limited in scope. Colonel Lang controlled access to the facility. Only certain officers could be approached. Only certain opportunities presented themselves. She applied for and received permission from the Ministry of Shadows to expand, to become mobile, to take contract work throughout Belgium. She was assigned to hospitals in Brussels, Liège, and Antwerp.

She was given false papers identifying her as a civilian nurse. She was given a cover story that she had been displaced from a bombed-out convent. The monastic network supported her. They provided funds. They provided safe houses. They provided intelligence on targets.

In 1943 and 1944, Sister Maria killed 12 more officers under this new operational structure. 12 more Nazis who disappeared into the mathematics of occupation, written off as casualties of duty. But the monastery, her true home, remained her primary base of operations, and Colonel Lang remained the target she could not reach.

In July 1943, the Gestapo arrived at the monastery. Six men, black uniforms. The interrogator was a Sturmbannführer named Klaus Müller, 45 years old, known to the resistance as an expert in obtaining confessions through psychological rather than physical torture. He had come for Michel Verdier. Not Sister Maria, not the network, just Verdier.

Someone had betrayed him. The resistance network had a leak. Intelligence on Verdier’s whereabouts had been sold to the Gestapo for money. Sister Maria watched from the library as they searched the monastery, turning over furniture, probing the foundations, opening the hidden chambers where the resistance had stored weapons and documents. They found nothing.

The network had been evacuated in the hours before the Gestapo arrived. Müller’s interrogation method was known, and they had expected his arrival sooner or later, but Müller stayed at the monastery for four days. He remained in Colonel Lang’s office, reviewing files. He stayed because he suspected the pattern.

37 German deaths, an impossible coincidence. He had read Gruber’s medical report. He had read the formal conclusions that all the deaths were natural. But Müller’s mind did not accept coincidence. On Müller’s third day at the monastery, he requested Sister Maria. She entered the abbot’s study. Müller sat behind the desk.

He was thin. His face was etched with old scars from a wound suffered in Poland. His eyes were the most intelligent eyes she had ever seen on a German officer. He looked at her, and for the first time, Sister Maria felt genuine fear. Not the fear of capture, the fear that this man might actually understand. “Sit down, Sister Maria,” he said in German. She sat. “I am here to investigate the disappearance of Michel Verdier.”

He opened a file. It was her personnel file, created by the Germans during the occupation. “Born Leuven, 1904. Nun since 1924.” He stood. He walked to the window. “They say you are a very devout woman. A servant of God.” Sister Maria did not reply. Müller smiled. “Some of your colleagues call you the Saint of Leuven.” He turned back to her. “Is that an apt title?”

Sister Maria’s hands remained folded. She did not move. “And yet,” Müller continued, “all logic suggests that you are the very person who has been committing these killings.” He walked toward her. He stood directly in front of her. He was very close. She could smell the coffee on his breath. She could hear the small adjustments of his uniform as he breathed. “I cannot arrest you,” he said softly.

“Because if I arrest you, and you are innocent, which you claim, I will have created a martyr. I will have created a symbol of Nazi oppression against the Church. And that symbol would be far more damaging to the occupation than any actual assassin.” He stepped back.

“Furthermore, if you are guilty, if you have indeed killed 37 German officers, your arrest will only inspire a thousand other women to adopt similar methods.” He returned to the desk. He sat down and said finally, “I do not entirely disagree with what has been done. I am a military man. I understand the mathematics of occupation.”

“I understand that 37 deaths spread out over three years in the officer corps represents a significant degradation of command effectiveness.” He opened a drawer. He pulled out a document. “This is an order signed by Colonel Lang. You are being reassigned as a hospital aid to the Brussels hospital. You will begin work tomorrow. You will have false papers identifying you as Sister Marie Clare, a civilian nurse from the Charleroi convent.”

“This is a transfer, not a punishment. Do you understand?” Sister Maria nodded slowly. “You are being removed from this monastery, because if you remained, I would have to make an arrest. And if I make an arrest, I would have to interrogate you. And I suspect that under interrogation, you might make statements that would compel me to take actions I do not wish to take.” He paused.

“I am offering you the opportunity to continue your work elsewhere, to disappear from my jurisdiction, to become someone else’s problem.” He stood. He gestured toward the door. “You are dismissed, Sister.” She stood. She walked to the door. As her hand touched the frame, Müller spoke again. “Sister Maria, in another world, in another time, you and I might have fought on the same side.”

She walked out without replying. Within hours, she had left the monastery. Within a day, she was in Brussels with false papers and a new identity. Within a week, the hospital became the center of a new phase of operations. October 1944. The Germans were losing. The Allies had landed in Normandy. The Soviet advance from the east was accelerating.

Germany was being ground between two advancing armies. Colonel Otto Lang received new orders. The monastery and the Leuven Library were to be evacuated, but not for transport to Germany—for destruction. Berlin had decided that the medieval collection, thousands of pages that could not be moved without damage, should be burned. The library that had stood for 400 years was to become ash.

The manuscripts that had survived the religious wars of the 16th century, the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, were to be destroyed by the Nazis. Sister Maria learned of this order through the resistance network. She heard it as a physical sensation, a tearing in her chest, a moment of clarity beyond thought.

She had killed 52 men. She had operated in the darkness for four years. She had done unspeakable things in the name of the resistance. But the library was different. The library was not a military target. The library was human civilization itself. It was the accumulated knowledge of centuries.

It was the dream of human transcendence that no empire was allowed to destroy. She made a decision in that moment, a decision unlike any other. She would not hide this killing. She would not make it appear as a natural death. She would make it visible. She would give it meaning. She requested a meeting with Colonel Lang through official channels.

She claimed she had vital intelligence about a resistance cell operating in Brussels. She claimed the intelligence could not be transmitted through normal military channels. It had to be delivered in person. October 15, 1944, late evening. The monastery was almost empty. Most of the German garrison soldiers had been transferred to positions closer to the front line.

Colonel Lang remained, and Sister Maria entered his quarters with her final hollowed-out Bible. This one was different from the others. It contained no poisons, no weapons, no carefully calibrated toxins designed to mimic the symptoms of natural disease. It contained a Yugoslavian F1 hand grenade, and beneath it, pressed against the pages in the exact center of the book, a note in German.

“This is for every book you tried to burn. This is for every idea you tried to extinguish. This is for the future you tried to destroy. My name is Sister Maria of the Leuven Convent. I have killed 52 of your officers over four years. This is the first death to bear my name. Let them know that resistance is not passive. Resistance is not subtle. Resistance is not silent. Resistance is the refusal to accept that evil will have the final word.” She entered his office. He was alone. He was writing reports. He did not look up. “Colonel Lang,” she said, “I have intelligence.” He looked up. He saw her. He saw the Bible in her hands.

And in that moment, four years of war and occupation and suspicion crystallized in his eyes. He understood everything. In a single instant of recognition, he understood that the strange pattern of deaths in his monastery, the impossible coincidences, the perfectly natural causes, all of it had been her, this silent nun, this invisible woman who had walked past him in corridors for four years.

This woman whose face he had seen 500 times without actually seeing her. He opened his mouth to speak, to call for guards, to do anything. Sister Maria pulled the pin. She held the grenade in her right hand. She placed the Bible on his desk with her left. “I am sorry, Colonel,” she said. “I once took vows of peace, but the world made that impossible.” The explosion was not loud. The room was small. The blast was contained.

Colonel Lang died instantly. His body was never fully recovered, but his last moment was one of recognition. He understood in his final instant of consciousness that he had not been defeated by armies, but by the silent courage of a single woman. The Leuven Library would survive. The manuscripts would endure.

The knowledge of four centuries would pass intact into the postwar world. The guards outside heard the explosion. They rushed in. What they found was Sister Maria, covered in Colonel Lang’s blood, standing in the center of the destroyed office. She was alive. She had stood at the correct distance. She had precisely calculated the blast radius. She was wounded. Her left arm was gashed.

Her face was cut. Her hearing was permanently damaged by the blast. But she lived. When the guards attempted to restrain her, she offered no resistance. She allowed herself to be captured. Within hours, she was in Gestapo custody. Within hours, she was being interrogated. The torture lasted three days.

The interrogators, not Klaus Müller, who had been transferred weeks earlier, did not know who she was. They did not know her history. They assumed she was a resistance agent who had managed to infiltrate the German command structure. They used electricity. They used ice water. They used sleep deprivation and psychological manipulation. They used every technique designed to break the human mind.

But Sister Maria did not break, because she had already made her final choice. She had already destroyed the one thing she needed to destroy. The library was no longer going to burn. Colonel Lang was dead. The command structure she had targeted for four years was in chaos. Whatever happened to her now did not matter. What she had done was choose the visible act over the invisible.

She had chosen to sacrifice her greatest weapon, anonymity, to save something she loved more than her own survival. She was transferred to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. She arrived on October 23, 1944. She died on February 8, 1945. Official cause of death: pneumonia and malnutrition. But the women in the barracks who saw her die said something else. They said she walked to the gallows, where she was finally executed, as if she was returning to the convent chapel. They said her face was at peace. They said her lips moved as if in prayer, but the prayer was not a plea for mercy. It was something else, something that sounded like gratitude. After the war, the Leuven Library was liberated intact by Allied forces. The Nazis did not burn it. No books were lost.

The collection survived because one woman made the decision to break her vows of silence and non-violence to protect something that transcended the immediate horror of the war. In the decades after 1945, historians began to piece together what had happened at the monastery. The surviving network of resistance fighters came forward. They described the woman they called “the silent assassin.” They described the pattern of deaths. They described the impossible mathematics behind it. 52 German casualties, all officially natural, all perfectly hidden. But Sister Maria’s true identity remained partially obscured. No one could prove beyond a doubt that she was the sole actor.

No one could trace every death directly back to her work. The network had been careful. The operations had been distributed. The trail was deliberately obscured. Some historians dismissed the stories as legend, as myth, the kind of narrative that tends to grow after a war, where ordinary people become heroes and heroes become gods. Other historians found the documentary evidence. They found the cipher list in the monastery safe.

They found the notes in German that detailed each operation with clinical precision. They found medical records that, upon close examination, contained anomalies that could only be explained by poisoning. But most importantly, they found the letter written by Standartenführer Friedrich Gruber.

The letter that read: “I have discovered your work. I am a physician. I recognize practiced violence when I see it.” And they found something else. In 1946, Friedrich Gruber went to work for the Americans. He became part of Operation Paperclip, the secret program that recruited German scientists and engineers for American use during the early Cold War.

He died of natural causes in 1953. His obituary mentioned that he was a brilliant medical researcher. It did not mention that he had chosen to side with a resistance assassin. It did not mention that he had, in his own way, committed treason against the regime he nominally served. The question that history never quite answered was this.

How many German officers survived the war because Standartenführer Gruber kept their medical files off the radar? How many families, descendants of men who would have been executed for war crimes, were never born because one man decided that his oath to the Nazi regime was less binding than his oath to humanity.

The mathematics of history rarely works in clean lines. The resistance network Sister Maria belonged to is estimated to have saved 2,847 lives. Jews smuggled out of Belgium. Partisan fighters protected and cared for. Families hidden and fed. Soldiers who deserted the Wehrmacht and were helped to escape to Switzerland or France.

But the network did not save these lives through abstract ideology or distant strategy. It saved them through precise personal action—through Sister Maria. Through the 52 deaths, through the hollowed-out Bible that became the symbol of resistance. After the war, the hollowed-out Bible was placed in a museum in Brussels. It rests in a glass case behind protective glass with a plaque explaining its history.

Thousands of visitors pass it every year. Some are moved to tears. Some are repulsed by the violence it represents. Some are confused, uncertain whether the story is true or whether it is legend. But one fact remains clear. The mathematics of occupation changed because of the choices of that single woman. The German command structure in Belgium was disrupted. Operations were delayed.

Plans were abandoned. Not because of conventional military action, not because of direct combat, but because 52 officers died under mysterious circumstances over four years. Because no one could prove it was murder. Because the system itself, the Nazi obsession with order and documentation, created the perfect cover for the crimes. Sister Maria never wrote a memoir. She never gave interviews.

She never explained her philosophy or her methods. What we know of her comes from the testimonies of others, from the documents left behind, from the decoded cipher lists, from the stories of the network that survived her. What emerges from those sources is a portrait of extraordinary intellect applied to moral necessity.

Here was a woman trained in the contemplative arts, illumination, manuscript preservation, the quiet scholarship of convent life. Here was a woman who had taken vows of silence and non-violence. And here was that same woman, by the logic of history and circumstance, transformed into an assassin.

The question that haunted the postwar interrogations, the question asked by multiple historians and investigators, was always the same. Did she regret it? We have no direct answer, but we have the note she left behind in the monastery archives. We have a single additional notation in her hand, dated two days before her final operation against Colonel Lang: “I am not innocent, but I am not guilty.”

The postwar world did not know quite what to do with Sister Maria’s legacy. She did not fit the neat categories of resistance heroism. She was not a soldier. She was not a commander. She was not a politician or a diplomat or an organizer. She was a woman who had used poisons and explosives to protect something she loved.

She was a woman who had violated her sacred vows because the world around her had become so corrupt that vows no longer made sense. She was a woman who chose to carry blood on her hands so that others could live. The Belgian government posthumously awarded her a medal of valor in 1946. The Catholic Church was less enthusiastic.

Some bishops argued that her actions, regardless of her moral intent, violated foundational tenets of the Christian faith. Others argued that in the context of genocide and totalitarianism, conventional moral categories no longer applied. That debate has never been fully resolved. Even today, more than 70 years after her death, Sister Maria remains a controversial figure. To some, she is a saint.

To others, she is a warning about the dangers of moral relativism. To still others, she is simply a human being who did the best she could under impossible circumstances. The hollowed-out Bible itself has become a philosophical artifact as much as a historical one. It represents the paradox of resistance, the recognition that sometimes peace must be fought for, that sometimes silence must be broken, that sometimes the most sacred act is the refusal to accept that evil is inevitable.

The war ended in May 1945. The monastery in Leuven was liberated by Allied forces. The library remained intact. The manuscripts survived. The knowledge accumulated over four centuries was preserved for the postwar world. What survived with it was a question. A question that Sister Maria raised by her life and death. In a world where evil has organized itself into total institutions of violence and oppression, what are the duties of individuals committed to non-violence? When the state itself becomes criminal, when the machinery of government is dedicated primarily to committing atrocity, when negotiation and law and appeals to conscience have all been exhausted.

What then? Sister Maria lived and died inside that question. She found an answer. An answer written in poison and explosives. An answer that broke her vows but saved lives. An answer that was violence but prevented greater violence. An answer that was not heroic in the conventional sense, but was necessary in the unconventional reality she inhabited. The Leuven Library still stands today. Visitors can walk through its halls and see the manuscripts that Sister Maria helped to protect. They can see the hollowed-out Bible in the Brussels museum. They can read the sparse historical records of the woman who killed 52 German officers and died in a concentration camp at the age of 41.

What they will not find is moral clarity. What they will not find is a simple judgment. What they will find is the same thing Sister Maria found. The recognition that history at certain moments demands ordinary people become extraordinary, that ordinary people become murderers and saints simultaneously, that ordinary people face choices that no philosophy has adequately prepared them for. The mathematics of occupation was precise.

52 deaths, four years, a pattern hidden in plain sight. A conspiracy so invisible that it was only seen when the Nazis themselves tried to account for what had happened. And even then, they could barely believe it. But the mathematics of legacy is even more precise. The 2,847 lives the Ministry of Shadows saved. The books preserved because one woman refused to let them burn.

The families that existed after the war because partisans were cared for and protected. The descendants of hidden Jews who would never have been born without Sister Maria’s sacrifice. That is the final irony of her story. This woman who took vows of peace and contemplation, whose life was supposed to be invisible and passive, became one of the most effective active resistance fighters of the entire war.

This woman who chose violence as a last resort, through that violence, saved more lives than most soldiers killed in a century of combat. Whether that means the violence was justified, I cannot tell you. But I can tell you that it happened. I can tell you that it worked.

I can tell you that civilization was preserved not by armies alone, but by one woman with a hollowed-out Bible and the courage to break her vows when the world demanded it. The monastery still exists. The library still stands. And somewhere in the memory of human history, Sister Maria remains, not as a hero or a villain, but as a question, as the question that every generation must answer for itself.

What will you do when the world demands you become something you never wanted to be? Some will say she should have remained silent, remained non-violent, allowed the Nazis to do what they would do. Some will say that her violence was justified, that her 52 murders were an appropriate response to genocide.

Most will say something in between, that she did what she could given the circumstances, and that her legacy is neither purely heroic nor purely tragic, but something more complex and human than any category can capture. What is certain is this. The hollowed-out Bible exists. The Leuven Library survived. 52 German officers died under mysterious circumstances. And a woman forgotten by official history for decades became the face of quiet resistance against totalitarianism. In a world that often forgets such stories, Sister Maria’s hollowed-out Bible reminds us that history is not made by armies alone. It is made by individuals who face impossible choices and make decisions that echo through generations. It is made by women in habits carrying poisons in sacred texts.

It is made by people who understand that sometimes the most sacred act is the act of defiance. And it is made by those who remember and retell the stories that official history attempts to erase.

News

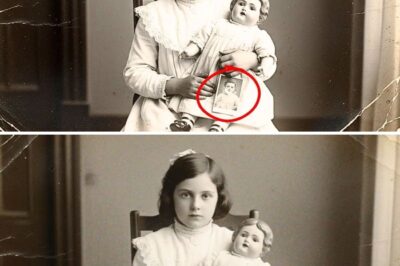

This photograph from 1905, showing a girl with a toy, seemed harmless – until restoration revealed something sinister.

On April 14, 1905, photographer Thomas Wright took a portrait in the parlor of a Boston, Massachusetts home of 7-year-old…

The widow bought a young slave for 17 cents. She had no idea who she had once been married to.

The widow, lonely and lost after her husband’s death, bought the young man almost impulsively, without suspecting the story he…

The landowner gave his obese daughter to the slave… Nobody suspected what he would do to her.

The Fazenda São Jerônimo stretched across hectares of coffee and sugarcane, red earth clinging to the boots, a humid heat…

German general captured in 1945… What the Americans did next changed Germany forever.

A German general stands in a field in Maryland. His Iron Cross glints in the spring light. American soldiers watch…

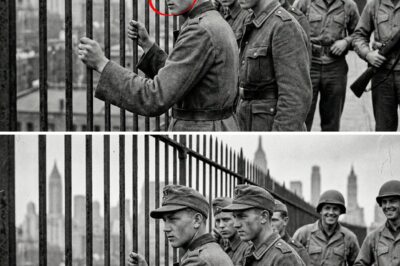

What did the USA do with the child prisoners in 1944? The story of this German boy will shock you.

A 12-year-old boy stands on a pier in New York Harbor. His hands are trembling. A woman in white approaches…

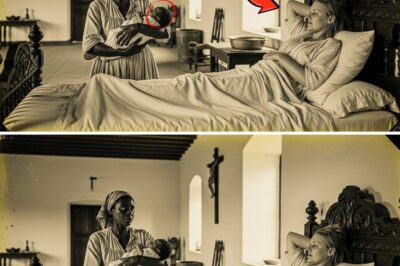

Ana Belén: THE SLAVE who witnessed the birth of the child whose skin revealed the hidden betrayal

In the summer of 1787, when the air in the Valley of Oaxaca burned like a living ember and the…

End of content

No more pages to load