A German general stands in a field in Maryland. His Iron Cross glints in the spring light. American soldiers watch him observe something impossible. May 1945, Fort Meade, Maryland. A Wehrmacht general faces his first day as a prisoner. This is the story of how three years behind barbed wire destroyed everything Friedrich Kesler believed and rebuilt him as the architect of the army of democracy.

The Surrender and the Journey May 8, 1945. Bavaria crumbled beneath Allied boots. Major General Friedrich Kesler stood next to his staff car, watching his Panzer Division surrender. Dust rose from the idling tank engines. American infantry advanced in clean lines. Kesler unbuckled his sidearm. The weight left his hip. 23 years of service ended with that gesture.

He expected immediate execution. The Führer’s final orders had been explicit: no surrender. Fight to the last bullet. Death before dishonor. Kesler had disobeyed. His 2,000 men would live. The leather holster hung empty on his uniform.

An American Captain approached. Young, perhaps 25. The Captain’s eyes showed no hatred, only efficiency. “Your name and rank, sir.” Kesler’s English came slowly. “Generalmajor Friedrich Kesler, Third Panzer Division.” The Captain consulted a clipboard. “High-value prisoner. You’ll be sent across the Atlantic.” Kesler gasped. Across the Atlantic meant America. Not summary justice in a Bavarian forest. Not a hasty tribunal in occupied Germany. America, the industrial behemoth that had crushed the Reich with its limitless resources, the country he had fought for four years without ever seeing.

3 days later, Kesler stood on the deck of a troop transport. Gray waves stretched into infinity. Behind him, Europe burned. Ahead lay an unknown fate. 47 years old, a professional soldier since age 18. Commander of tank operations from Poland to Normandy. Every decoration the Wehrmacht conferred, save the Knight’s Cross. All of it meant nothing now. The Atlantic crossing took 11 days. Kesler shared a cabin with three other generals. They spoke little. What was left to say? Field Marshal von Rundstedt’s words echoed in Kesler’s mind: “The professional soldier’s duty ends with defeat.” But defeat to what? What came next?

The Shock of Fort Meade Fort Meade, Maryland. Late May 1945. The camp stretched over 300 acres of manicured lawn. White barracks stood in precise rows. Watchtowers rose at hundred-yard intervals, but no machine guns. No searchlights sweeping at night. American soldiers walked their posts casually. Some smoked cigarettes, others conversed. Kesler’s stomach dropped. This was not a penal camp.

He was processed through an administration building. Medical check, delousing. Uniform exchange. American work clothes replaced his Wehrmacht gray. An officer handed him a thick booklet. English text: camp regulations and class schedule for the education program. “Education program?” Kesler asked. “You’ll see tomorrow, General. Welcome to Fort Meade.”

That first night, Kesler lay on a steel cot. The barracks housed 30 beds. Electric lights hummed overhead. Through the window, the Maryland spring night smelled of grass and rain. Nothing resembled the cordite and diesel of the Eastern Front. Nothing resembled the ash-laden air of burning German cities. His hands trembled, not from fear, but from lack of purpose.

A Colonel in the next cot spoke. Oskar Brener, Panzergrenadier Commander, Army Group Center. “They feed us three meals a day,” Brener whispered. “Real food, meat, bread, coffee with sugar.” “Impossible,” Kesler said. “I’ve been here 3 weeks. It is true.” Kesler turned to the wall. The Geneva Convention required adequate rations for prisoners, but Germany had starved Soviet prisoners by the millions. He had seen it, not directly participated, but seen. Wehrmacht logistics officers had explained it: insufficient supplies for all. Prioritization in favor of German troops. Soviet prisoners were non-protected combatants under international law. The rationalizations felt hollow now.

Morning arrived with a bell at 6:00 AM. Breakfast in a mess hall. Long tables, metal trays, American soldiers serving behind a counter. Kesler moved through the line. Scrambled eggs, bacon, toast, orange juice, coffee. His tray filled up. He found a seat. The egg was real. The bacon crisp, the coffee strong and sweet. Kesler ate slowly. Across from him, Brener devoured his meal methodically. “Every day like this,” Brener said between bites. An American lieutenant stood at the entrance to the hall. Young, confident, he raised his voice. “Gentlemen, the education program begins at 8:00 AM in Building 7. Attendance is mandatory. Interpreters will be provided.” Kesler finished his coffee. The cup was ceramic, not tin. Small details, but they accrued. This camp operated on rules Kesler did not understand.

The Confrontation with Evil Building seven was an auditorium, 200 seats, a screen. American officers stood at the entrance checking names against lists. Kesler entered, found a middle seat. Around him, Wehrmacht generals and colonels filled the rows. Conversation buzzed, speculation, fear, confusion. The lights dimmed.

At precisely 8:00 AM, an American Major walked onto the stage. “Good morning, gentlemen. I am Major Robert Harrison. For the next 3 years, this facility will be your home. You will study, you will read, you will watch, you will learn. What you learn will determine whether Germany has a future.” The Major nodded to a projectionist.

The first film began. Grainy black-and-white footage. A train. Cattle cars. People crowded inside. The camera followed the train to a gate. German text: Arbeit macht frei. Work sets you free. Auschwitz.

Kesler leaned forward. He knew of concentration camps, labor camps for political prisoners and racial undesirables, harsh conditions, high mortality, necessary measures to protect the Reich from internal enemies. Or so the SS had explained it.

The film continued. The train stopped. SS guards opened the cattle car doors. Families stumbled onto a platform. Men separated from women. Children ripped from mothers. An SS doctor gestured with a casual flick of his hand, left or right. Left meant immediate death in gas chambers. Right meant temporary survival for forced labor.

Kesler’s jaw clenched. This could not be real. The camera entered a building. Naked corpses. Hundreds. Thousands piled like firewood. Emaciated limbs. Open mouths. Eyes frozen in final agony. An American narrator spoke: “17,000 bodies found at Bergen-Belsen, 13,000 at Dachau. Over 1 million at Auschwitz-Birkenau.” The auditorium was silent. 200 German officers watched genocide documented in clinical detail.

The film showed gas chambers, Zyklon B canisters, crematorium ovens, efficiency reports from camp commandants, daily death quotas. The Final Solution, not a military operation, not combat losses. Systematic industrial murder of 6 million Jews, plus millions of Poles, Soviets, Roma, disabled people, political dissidents. Kesler’s hands gripped the armrests. His breathing was shallow.

He had served the Wehrmacht, not the SS. He had fought enemy soldiers, not annihilated civilians. But the Wehrmacht had provided logistics, guarded transport routes, known or chosen not to know.

The film ended. The lights came up. Major Harrison returned to the stage. “Gentlemen, this is what you served. Not German honor, not European civilization, not defense against Bolshevism. This industrial genocide, the greatest crime in human history.” Harrison paused. He let the words sink in. “Some of you will deny. Some will rationalize. Some will claim ignorance. But you cannot unsee what you have just seen. The question now is: ‘What will you do with this knowledge?’”

Kesler walked out of the auditorium in silence. Around him, officers murmured. Some wept. Some argued the footage was propaganda, Soviet lies, Allied fakery. Kesler said nothing. His mind replayed the images: the faces of the children, the piled bodies, the bureaucratic efficiency of it all. He had served this system, worn its uniform, followed its orders, believed its propaganda about defending Western civilization, and behind his Panzer Divisions, this machinery of death had operated with German thoroughness.

Democracy and Morality The education program continued daily. American instructors taught German history from new perspectives. The failures of the Weimar Republic, Hitler’s rise through democratic processes corrupted by demagoguery, the Reichstag fire, the Enabling Act, the step-by-step destruction of constitutional government—each step logical, each step leading to tyranny.

Kesler attended lectures on democracy, the American Constitution, checks and balances, separation of powers, federalism, individual rights protected from state overreach—concepts alien to his Prussian military training. Officers served the state. The state embodied the will of the nation. Obedience was virtue. Questioning was treason. But what happened when the state became criminal?

The camp library contained 10,000 books previously banned in Germany. Kesler read Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, Lion Feuchtwanger. German authors who had fled Nazi persecution. Their words described Germany from the outside: a nation that had betrayed its own cultural heritage for racial mythology and military aggression. He read American newspapers, the New York Times, the Washington Post—free press, multiple viewpoints, criticism of government policy published openly, no censorship, no Ministry of Propaganda. The concept bewildered him. How could a nation function without a unified message? Yet America had functioned, had mobilized, had outproduced Germany tenfold. Democracy had proven stronger than dictatorship.

Summer 1945 turned to autumn. Kesler’s worldview tore open further each day. The camp administration organized debates. German officers argued with American political science professors. Topics: The nature of military loyalty, the soldier’s responsibility for the crimes of his government, the relationship between obedience and conscience. Kesler rarely spoke. He listened, absorbing.

One debate struck him particularly. Colonel Brener argued: “A soldier’s duty is to follow orders. Without obedience, armies break down. We followed orders. We are not responsible for political decisions.” Professor David Cohen countered: “The Nuremberg Trials will establish a new principle. Superior orders is not an absolute defense. If an order is manifestly criminal, soldiers have a duty to refuse. Moral responsibility cannot be ceded to the hierarchy.”

Brener’s face flushed. “That is impossible. That destroys military discipline.” “No,” Cohen said gently. “It creates a military bound by law and ethics, not blind obedience. The Prussian military tradition produced the most technically capable army in Europe. It also produced officers who served genocide without protest. Technical capability without moral judgment is barbarism in uniform.”

The words hit Kesler like artillery. His entire career had been built on obedience. Follow orders, execute missions, trust superiors to make strategic decisions. He had been a perfect Prussian officer, and that perfection had made him complicit in atrocity. That night, Kesler wrote in a journal provided by the camp, his first entry: I believed I served Germany. I served criminals who kidnapped Germany. What is a soldier’s duty when his government betrays everything worth defending?

The Birth of the “Citizen in Uniform” Winter 1945. The camp was well-heated. American efficiency. Kesler walked the camp perimeter. Snow covered Maryland in white silence. Watchtowers stood empty at night. No dogs, no random searches. Prisoners received Red Cross packages. Letters from Germany arrived. Heavily censored, but still. His wife wrote from Düsseldorf. The city was rubble. Food scarce. Occupation forces strict, but not brutal. She asked when he would return. Kesler had no answer.

The education program intensified. Films showed American industrial capacity. The Willow Run factory producing a B-24 bomber every 63 minutes. Detroit’s tank production. Liberty Ships launched weekly. The numbers were staggering. Germany had fought not only Allied armies but Allied factories. The war had been mathematically unwinnable since 1941. Kesler realized Hitler had led Germany to suicide. Not glorious defeat, not heroic last stand. Suicide, deliberate, ideological. The Führer had preferred the destruction of Germany to compromise or surrender. And the Wehrmacht had followed those suicidal orders for four years after defeat became inevitable. Why? Kesler asked himself nightly. Why did we continue?

The answer came slowly. Because to stop would have been to admit the entire enterprise had been criminal from the start. Because to stop meant facing complicity. Because military culture valued honor. And honor meant never admitting error. Never questioning leadership. Fighting to the death rather than facing moral failure. Prussian honor had become a suicide pact.

Spring 1946 marked one year in captivity. The camp administration announced a new program: Democratic Leadership Training. Selected prisoners were to study the civilian-military relationship in democracies. How elected governments controlled armed forces. How parliaments approved budgets and declared wars. How officers served constitutions, not individual leaders. Kesler was selected. 20 generals and colonels participated in an intensive three-month course. American instructors lectured on George Washington’s resignation of his command, returning military power to civilian authority. On the Potsdam Conference to reorder post-war Europe. On the impending Nuremberg judgments.

The judgments arrived in October 1946. 12 death sentences, seven prison terms, three acquittals. Göring, Ribbentrop, Keitel, executed. The Wehrmacht High Command was declared a criminal organization for its role in war crimes and genocide. Kesler read the verdicts in silence. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel had been his ultimate superior, a professional soldier. Obedient to the end, executed as a war criminal. The distinction between Wehrmacht and SS had collapsed. Service to the Nazi regime made one complicit in its crimes, regardless of specific duties.

That night, the prisoners held a solemn gathering. Colonel Brener spoke. “They hanged Keitel for following orders. We all followed orders. Are we all criminals?” Kesler stood up. The first time he had spoken publicly in 18 months. “Yes.” The room fell silent. “We are criminals,” Kesler continued, his voice firm. “Not because we killed enemy soldiers in combat. That is war. We are criminals because we served a criminal regime. We enabled genocide by delivering military success that legitimized Hitler’s rule. We accepted promotions and decorations from a government that murdered millions. We claimed ignorance while death camps operated behind our front lines. Yes, Colonel, we are criminals. The question is: What do we do now?”

The turning point came in December 1946. Major Harrison organized a special seminar. Topic: The future German army. Allied occupation authorities debated whether West Germany should be allowed armed forces at all. Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union created pressure for German rearmament, but how could a military be created that would never again threaten democracy?

Kesler listened as American strategists laid out their dilemma. Germany needed defense capability. But Germany with a traditional military could become a threat again. The Reichswehr had skirted the limitations of the Versailles Treaty, secretly rearmed, and prepared for a revanchist war. How to prevent a repeat?

Professor Cohen posed a question. “Gentlemen, you know German military culture. How would you design an army incapable of overthrowing democracy?” Silence. Then Kesler raised his hand. “Make the soldier a citizen first.” Cohen nodded. “Explain.”

“The Wehrmacht swore personal oaths to Hitler, not to Germany, not to the constitution, to a man. That made us complicit in his crimes. A new German army must swear allegiance to democratic law, not to leaders. Soldiers must have rights as citizens: freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, the right to refuse illegal orders. Officers must be educated in ethics and constitutional law, not just tactics. Parliamentary control over military budgets and deployments must be absolute. No military secrets from elected representatives.”

Kesler paused. The ideas flowed from 18 months of reading, reflection, and confrontation with his past. “The Prussian tradition valued honor without morality. We need morality that questions honor. A soldier who refuses a criminal order should be commended, not court-martialed. Obedience must be contingent on legality.” Harrison smiled. “General Kesler, you have just described the concept we call Innere Führung, or ‘Inner Guidance’—the internal leadership model, a citizen in uniform.”

The Legacy of Confession 1947 brought accelerated change. The Marshall Plan began rebuilding Western Europe. The Cold War hardened into confrontation. Occupation authorities prepared for West Germany’s eventual sovereignty. The question of rearmament became urgent. Kesler was moved to a special facility. 15 German officers were selected for advisory roles. They were to help conceptualize the future Bundeswehr, an army that served democracy instead of threatening it.

The work consumed Kesler. He drafted memoranda on command structure, parliamentary oversight mechanisms, training programs that incorporated constitutional law, ethics, and human rights. He argued against restoring the General Staff, which had been the Wehrmacht’s brain, planning wars of aggression and war crimes. The new military needed decentralized leadership, transparency, accountability.

Old colleagues resisted. Colonel Brener, also selected for the advisory group, fought every reform. “You are destroying military effectiveness. Soldiers need hierarchy, discipline, unquestioning obedience. This democratic nonsense will create a weak force.” “Good,” Kesler retorted. “A weak military cannot overthrow democracy. And we have proven that technically strong militaries serving criminal governments create catastrophe. I prefer a slightly less efficient military that respects human rights.”

The debates raged for months. Gradually, Kesler’s faction prevailed. The emerging Bundeswehr concept contained radical innovations: a Parliamentary Commissioner for Defense to investigate soldier complaints, mandatory ethics training, the right to conscientious objection, strict civilian control, no military involvement in domestic politics, integration into the collective defense structure of NATO.

1948, 3 years after surrender, Kesler stood before a review board. American officers and German civilian authorities from the nascent West German government, his decision for repatriation. “General Kesler,” the board chairman said, “You have completed re-education. You have contributed significantly to Bundeswehr planning. Are you ready to return to Germany and implement these reforms?” Kesler stood at attention—habit—then consciously relaxed his stance. Citizens did not stand at attention. “I am ready, but not as a General. I request a reduction in my rank. I cannot hold rank earned serving the Third Reich while building a democratic military.”

The chairman consulted papers. “Your contribution has been considerable. The occupation authorities recommend you return as a civilian advisor to the Ministry of Defense. No rank, no uniform, no military authority, but considerable influence. Acceptable.” “One more question, General. Do you believe German soldiers can be trusted with arms again?” Kesler considered. 3 years ago, he would have answered with Prussian certainty. Now he understood the complexity of the question. “Soldiers reflect their society and their training. The Wehrmacht reflected a criminal dictatorship and trained for conquest. The Bundeswehr must reflect democracy and train for defense. If we build the right institutions, yes, German soldiers can be trusted. But we must never again trust soldiers who serve leaders instead of law.” The chairman nodded. “Welcome home, Herr Kesler.”

The Legacy The transport flight back to Germany took 12 hours. Kesler watched the Atlantic beneath him. The same ocean he had crossed in 1945. A different man made the return journey. Germany was in ruins. Frankfurt Airport operated from makeshift structures. American transport planes landed constantly. Marshall Plan deliveries, occupation troops, bureaucrats rebuilding governance. Kesler stepped onto German soil. The smell was familiar. Dust, concrete, diesel, home. A car drove him to Bonn, the provisional capital. The Ministry of Defense occupied a requisitioned hotel.

Kesler met Theodor Blank, the civilian plenipotentiary overseeing rearmament planning. Blank was a former trade unionist. No military experience. Precisely what the new Germany needed. Civilians controlling military development. “Herr Kesler,” Blank said, shaking his hand. “Your memoranda preceded you. Impressive work. But implementing these ideas will face resistance. Many former Wehrmacht officers consider your reforms treason to military tradition.” “Military tradition gave us Hitler,” Kesler countered. “We need new traditions.”

The work began immediately. Kesler joined a team drafting the Bundeswehr’s rules. They debated every detail. Should soldiers salute? Yes, but only in service and to superiors, not to political leaders. Should Germany have conscription? Yes, but with generous conscientious objection provisions and civilian service alternatives. Could former Wehrmacht officers serve? Selectively, with vetting and re-education. The fiercest battles concerned Innere Führung, the leadership philosophy. Old guard officers demanded traditional discipline. Kesler insisted on the citizen-soldier model.

Soldiers had political rights, could vote, could join political parties, could criticize politics off-duty, could refuse illegal orders without punishment. “You will create a debating club, not an army,” General Hans Speidel argued. Speidel was a Wehrmacht veteran, later a NATO commander, a brilliant strategist, but wedded to traditional military culture. “Better a debating club than obedient executioners,” Kesler countered. “We had the most disciplined army in Europe. We used that discipline to commit genocide. I prefer to risk a slightly less disciplined force that respects humanity.”

The debates lasted years. Gradually, Kesler’s vision prevailed. The Bundeswehr took shape. Parliamentarily controlled, defensively oriented, integrated into Western alliances, committed to democracy and human rights. Not perfect, but fundamentally different from the Wehrmacht.

1955, the Bundeswehr was formally established. Kesler attended the ceremony in Bonn. No military uniform for him. Civilian suit, gray wool, simple tie. He watched young German soldiers swear their oath: “I swear to faithfully serve the Federal Republic of Germany and bravely defend the law and freedom of the German people.” No loyalty to a leader, no obedience to superiors. Service to democratic law and human freedom. The distinction mattered.

Theodor Blank, now Minister of Defense, approached. “Your work is done, Herr Kesler. The Bundeswehr embodies the principles you fought for. Will you continue to advise?” Kesler shook his head. “No. Younger men must lead now. Men without Wehrmacht pasts. I can advise, but I cannot lead. My past disqualifies me.” “You have transformed yourself. That should inspire others.” “Perhaps. But transformation requires facing the evil one enabled. Most men cannot face it. I only managed because Americans forced me to watch films I could not unsee, gave me books I could not unread, asked questions I could not evade. Three years at Fort Meade destroyed Friedrich Kesler, the Wehrmacht General. I am someone else now.”

Blank smiled sadly. “Who are you now?” “A man who understands that obedience without conscience is evil. That military professionalism without moral judgment enables atrocity. That democracy is fragile and requires citizens who question authority. I am a warning, Herr Minister, a cautionary tale. Use me as such.”

Kesler spent his remaining years writing memoirs, essays, and lecturing at military academies. Always the same themes: the danger of blind obedience, the necessity of moral courage, the soldier’s responsibility to refuse criminal orders. His lectures made audiences uncomfortable. Young Bundeswehr officers squirmed. They wanted pride in their service. Kesler offered critical reflection instead.

1963, at the Bundeswehr Command and Staff College in Hamburg, Kesler spoke to officer candidates. “You wear German military uniforms. I did too. Mine bore the Wehrmacht eagle and the swastika. Yours bear the Iron Cross and democratic insignia. That difference is everything. But symbols alone do not guarantee morality. You must actively choose humanity over obedience when those values conflict. And they will conflict. One day, someone will order you to do something that feels wrong. In that moment, your character will be tested. Will you follow orders, as I did? Or will you have the courage I lacked? The courage to refuse?”

A young lieutenant raised his hand. “Herr Kesler, if we question every order, how can the military function?” “Question orders that violate law, ethics, or human rights. Obey orders that serve defensive necessity. Learn the difference. Study constitutional law. Read philosophy. Think for yourselves. The Wehrmacht produced technically brilliant officers who were moral imbeciles. Do not repeat that error. Be a citizen first, then a soldier.”

After the lecture, several officers approached. Some thanked him, others criticized. A Captain said: “You are teaching insubordination. That is dangerous.” Kesler looked the Captain in the eye. “More dangerous than obedient genocide? The Wehrmacht was insubordinate in nothing, followed every command, served efficiently, and enabled the greatest crime in history. I will take the risk of occasional insubordination over that outcome.”

Kesler was 76, frail, retired from public life, living in a small Bonn apartment. The Bundeswehr had matured, 30 years old, fully integrated into NATO, professional, competent, defensively oriented. It had passed the tests, never threatened democracy, never attempted a coup, never violated its constitutional limits. Kesler watched television news. The Bundeswehr participating in NATO exercises, modern tanks, professional soldiers, but also soldiers with rights, soldiers who studied ethics, soldiers who could vote and protest and question. The citizen-soldier model had worked.

A knock on his door. A young journalist from Deutsche Welle. Request for an interview. Kesler agreed. They sat in his modest living room. Books lined the walls. Mostly history, philosophy, political theory. “Herr Kesler,” the journalist began, “You are considered one of the intellectual founders of the Bundeswehr. Yet you never served in it. Why?” “I was disqualified by my past. The Wehrmacht General I was had no place in a democratic military. That man had to die so the Bundeswehr could be born.”

“Do you regret your Wehrmacht service?” “Every day. I regret following orders without question. I regret failing to investigate rumors of concentration camps. I regret prioritizing military success over moral responsibility. I regret 30 years of obedience that enabled genocide. Regret is insufficient. But it is what I have.”

“What changed you?” “Americans forced me to see what I had served, showed me films I could not deny, made me read books that explained how civilized Germany became genocidal. Three years of confrontation with the truth I had ignored. You cannot unsee certain things. Once you understand you have served evil, you either rationalize it or transform. Rationalization was impossible. Transformation was necessary.”

The journalist scribbled notes. “Do you believe it could happen again? Could Germany fall to dictatorship?” Kesler hesitated. Long pause. “Democracy is always vulnerable. It requires vigilant citizens. It requires soldiers who serve law, not leaders. It requires people willing to refuse, to question, to resist. The structure of the Bundeswehr helps: parliamentary control, civic education, human rights training. But structures alone do not guarantee democracy. People do. Every generation must choose democracy, must actively reject authoritarianism, must have the courage to disobey illegal orders. That is the lesson. Not that Germany was evil. But that any nation can become evil if citizens obey without conscience.”

Friedrich Kesler died in 1981. Small funeral, family and a few colleagues. No military honors. He had forbidden them. A civilian burial, simple headstone, no rank, no medals, just Friedrich Kesler 1902–1981. He learned too late, but he learned. His writings survived, becoming required reading at Bundeswehr academies: the officer who transformed himself from a Wehrmacht General to a defender of democracy. The man who faced his complicity and spent 30 years warning others. His story was uncomfortable. That was the point.

The Bundeswehr he helped design proved durable. Never threatened German democracy. Never attempted a coup. Never violated constitutional limits. Served in NATO peacekeeping operations. Delivered humanitarian aid, functioning as a military in a democracy should: competent but controlled, professional but accountable, strong but bound by law.

Kesler’s transformation demonstrated a difficult truth. Even those who serve evil can change. But change requires confronting reality, accepting responsibility, rejecting rationalization. Most Wehrmacht veterans never did that. They rationalized, denied, claimed victimhood. Kesler chose differently. Three years in an American camp destroyed his worldview. He rebuilt from the wreckage, just as Germany rebuilt from the wreckage.

The General who surrendered in Bavaria in 1945 was not the man who died in Bonn in 1981. The first served dictatorship through obedience. The second served democracy through critical awareness. In between lay three years of forced education, painful reckoning, and fundamental transformation. That transformation remains Kesler’s legacy. Not his Wehrmacht service, not his tactical brilliance, not his decorations. His legacy is the warning: Obedience without conscience enables evil. Military professionalism without moral judgment becomes barbarism. Soldiers must be citizens first: thinking, questioning, refusing when necessary. The Bundeswehr embodies this principle—imperfectly, but sincerely. German soldiers swear allegiance to the constitution, not leaders, study ethics alongside tactics, have rights alongside duties, can refuse illegal orders without penalty. That is revolutionary. That is what three years at Fort Meade, Maryland, ultimately produced. Not just a transformed general, but a transformed concept of soldiering.

Kesler never forgave himself for his Wehrmacht service. He should not have. Forgiveness would have been complacent. But he redirected his remaining years to ensure that future German soldiers were not subjected to the same moral failures he was. In that redirection, he found not redemption—that was not possible—but meaning. His grave in the Bonn civilian cemetery is unmarked save for the simple stone. No visitors but family, no ceremonies, no recognition. He wanted none. The work was important, not the man. The Bundeswehr was important, not its architect. Democracy was important, not military glory.

On the back of the tombstone, invisible to casual observers, a quote Kesler requested: “Nie wieder Gehorsam, immer Gewissen.” Four words, the reversal of a career, the hard-won lesson of a life. The epitaph of a general who learned too late but learned sincerely that humanity matters more than hierarchy, that morality matters more than orders, that citizenship matters more than soldiering. That lesson, learned in three years behind Maryland barbed wire, became the bedrock of democratic Germany’s military. Not a bad legacy for a man who began as a Wehrmacht General and ended as a servant of democracy.

News

The landowner gave his obese daughter to the slave… Nobody suspected what he would do to her.

The Fazenda São Jerônimo stretched across hectares of coffee and sugarcane, red earth clinging to the boots, a humid heat…

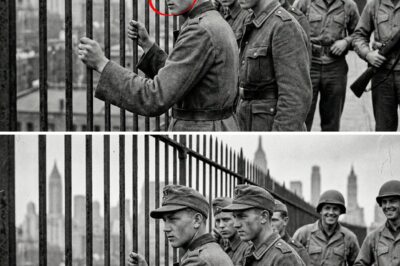

What did the USA do with the child prisoners in 1944? The story of this German boy will shock you.

A 12-year-old boy stands on a pier in New York Harbor. His hands are trembling. A woman in white approaches…

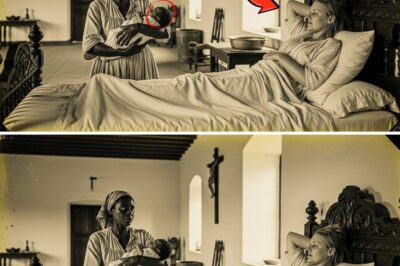

Ana Belén: THE SLAVE who witnessed the birth of the child whose skin revealed the hidden betrayal

In the summer of 1787, when the air in the Valley of Oaxaca burned like a living ember and the…

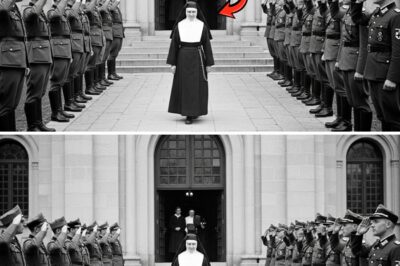

She murdered 52 Nazis with a hollow Bible – the deadliest nun of World War II

An excavated Bible rests on a wooden table. The pages are cut out. Inside, a German Luger pistol and three…

The Pine Ridge Sisters Were Found in 1974 — What They Revealed Had Been Buried for Generations

In the winter of 1974, two elderly women were discovered on a farm outside Pine Ridge, South Dakota. They had…

The farmer bought a huge slave girl for 7 cents… Nobody suspected what he would do.

Everyone laughed when he paid only 7 centavos for the woman almost 2 meters tall, who was deemed useless by…

End of content

No more pages to load