In the summer of 1787, when the air in the Valley of Oaxaca burned like a living ember and the cicadas sang their lament from the guava trees, Ana Belén heard Señora Leonor’s first cry from the main room of the Hacienda Santa Cruz de Tlacolula. It was a stifled cry, choked by decades of habit of showing no weakness before the servants.

Ana Belén set aside the washbasin where she was laundering linen sheets, dried her hands on her apron, and ascended the stone staircase leading to the master’s quarters. Her bare feet knew every step, every crack where the lime had chipped away during the previous year’s rains.

She had been in that house for 30 years, bought at the age of 13 in a market in Antequera, and had watched three generations of the Villarreal family grow up. This time, it would be different. She knew it from the tremor in the Señora’s hands when, three months earlier, she had begged her never to leave her alone during the birth. Promise me, Ana Belén. Swear it on your soul.

The Hacienda Santa Cruz dominated a valley where cochineal, scarlet, and corn were cultivated. The Señores Villarreal owned 200 souls, including black slaves brought from the coasts and indigenous servants who worked off debts inherited from their grandfathers. Don Rafael Villarreal, the master, had left for Mexico City six months earlier to attend to court business.

He had a lawsuit with the Dominicans over lands near Etla. His absence had stretched longer than expected, and the letters he sent every fortnight spoke of endless formalities, of papers lost, of officials demanding more money to expedite decisions. In the meantime, Señora Leonor, 42, had blossomed with an unexpected pregnancy that everyone attributed to divine will.

She had lost two children before, both before the second month of gestation. This time, the child held fast, grew, kicked. The hacienda’s chaplain, Fray Domingo, said it was a sign of blessing, that God was rewarding the piety of Doña Leonor, who had commissioned the building of a new chapel in the village of San Pablo. Ana Belén entered the room, closing the door behind her. Señora Leonor was lying on the carved wooden bed, bathed in sweat, her brown hair pasted to her temples. The labor had begun at sunrise, gentle at first, then increasingly intense. Now, the contractions came every few minutes.

Ana Belén had assisted in more than 50 births. She knew the body’s rhythms, the signs of danger, the silence that preceded death. She approached, palpated the swollen abdomen, estimating the child’s position. Everything seemed correct. “How much longer?” Doña Leonor asked, her voice strained. Before sunset, Ana Belén replied. “The child is coming well. It is strong.” The Señora closed her eyes.

Ana Belén, when he is born, when you see him, do not tell anyone anything, do you understand me? Her words were both a plea and a threat. Ana Belén nodded. She already knew. She had known for months. During the pregnancy, she had seen Doña Leonor head to the shed where the tools were kept, where Jacinto, the mulatto foreman, organized the work gangs.

Jacinto was the son of a slave and an unknown Spaniard, raised between the big house and the fields, a man of the master’s trust, in charge of maintaining order when Don Rafael traveled. He was 35, with the body of a worker tanned by the sun, large hands, and a soft voice that contrasted with his task of giving orders.

Ana Belén had seen them speak by the irrigation ditch that fed the fields. She had seen them walk to the edge of the property one October afternoon, before the rains began, where the mesquite trees offered discreet shade. She had not followed them; she did not need to confirm what she already understood. In a hacienda, secrets are like smoke. They can hide for a time, but they always look for a way out.

The birth lasted for hours. Ana Belén prepared infusions of chamomile and rue. She cleaned with cotton cloths. She held the Señora’s legs as her strength flagged. Outside, the sun began to set, painting the sky orange and purple. The bells of the chapel could be heard calling the Angelus. Fray Domingo had come twice to inquire, and Ana Belén had told him everything was going well, to pray and wait. The chaplain was a young man, newly arrived from Puebla, with no experience in the murky affairs that unfolded in the great haciendas. He saw what he wanted to see, a pious family, a devoted Señora, a master generous to the church.

When the child was born, Ana Belén received him with firm hands. It was a boy, as she had predicted. He cried vigorously, his lungs full of life. Ana Belén cleaned him with lukewarm water, cut the umbilical cord, wrapped him in a wool blanket, and then she saw it. The child’s skin was not white like Doña Leonor’s, nor light brown like Don Rafael’s. It was dark, the color of unsweetened coffee, with a tone that left no doubt about the blood flowing in his veins. The features, still undefined like those of all newborns, hinted at something else. The nose was wider, the lips thicker, the hair beginning to curl in small, tight coils.

Doña Leonor stretched out her arms, but when Ana Belén handed her the baby, she saw in her eyes the terror that had been hidden for nine months. The Señora looked at her son and said nothing, simply hugged him to her chest and began to weep silently. Ana Belén cleaned the blood, changed the sheets, prepared the bath for the mother.

She worked efficiently, without speaking, while her mind calculated the consequences. When Don Rafael returned—and sooner or later he would return—he would see the child, and then hell would begin. They cannot know, Doña Leonor whispered. If they know, he will kill me. He will kill the child, and you too, Ana Belén, for being here. Ana Belén did not answer. She knew the Señora was right. In the world of New Spain’s haciendas, a Spaniard’s honor was more important than any life. An illegitimate child was a disgrace, a mulatto child an abomination. The law allowed the husband to dispose of the adulterous wife and her offspring. Some did it with discreet poison, others with a quick knife at dawn. Always with the tacit blessing of the authorities, who understood that certain crimes were not crimes, but domestic justice.

That night, after Doña Leonor fell asleep exhausted with the baby in her arms, Ana Belén went down to the kitchen where the other maids were preparing tortillas and beans for dinner. No one asked about the birth. It was customary to wait for the Señora to officially announce the birth. The next day, the chaplain would come to baptize the child with holy water. Letters would be sent to Mexico City to inform Don Rafael. A small celebration with liquor and tamales would be organized. But Ana Belén knew that none of this would happen in the usual way.

The next morning, Doña Leonor sent for Jacinto. Ana Belén was present when he entered the room. The foreman held his hat in his hands, his back slightly bent in a sign of respect. When he saw the child, his face changed. First confusion, then understanding, finally something that resembled fear mixed with a tenderness he tried to hide.

He is your son, Doña Leonor said bluntly. Don Rafael will return in two weeks, according to his last letter. Before he arrives, this child must disappear. Jacinto took a step back. Disappear, Señora, what are you saying? Take him far away, to the village, to the coast, wherever. Find someone to raise him. I will give you money, whatever you need. Ana Belén watched the scene with a heavy heart. She had carried this child, cleaned him with her own hands. She knew what it meant to disappear from a master’s lips. Some children went to families who received them with affection, others were sold, others abandoned at the doors of convents, still others simply left to their fate on lonely roads where animals found them before people.

I will take him, Ana Belén said. The words came out of her mouth without thinking, as if another person were speaking. Doña Leonor and Jacinto looked at her. You? the Señora asked. I know a family in Tlacochaguaya, Ana Belén continued, inventing the story on the spot. Good people, no children, the woman owes me a favor. I will take the child there. No one will ask questions.

In reality, Ana Belén knew no such family. But she needed time to think, to find a way out that did not end with the dead child in a ditch. Doña Leonor nodded, too grateful to ask questions: Do it today, before anyone else sees him. I will give you 50 pesos, and when you return, we will say the child was stillborn. I have lost two before. No one will doubt it.

50 pesos was a fortune for a slave. It was equivalent to several years of work, if she had ever been paid at all. Ana Belén took the pouch the Señora handed her, wrapped the baby in a thick blanket, and left the room. As she walked down the hall, Jacinto caught up with her.

Where are you really taking him? he asked in a low voice. Ana Belén looked him in the eyes, To a safe place. I want to know where he is. He is my blood. Your blood will cost you your life if someone discovers it, Ana Belén replied. The Señora will forgive her husband’s adultery because she has no other choice, but she will kill you because you touched what belonged to her. Do you understand? Jacinto clenched his fists. I didn’t want this. No one chooses what is due to them, Ana Belén said. Now let me go. The less you know, the better.

Ana Belén left the hacienda with the child hidden under her shawl. She took the road east, where the hills, covered with oaks and pines, rose. She walked for hours under the sun that scorched the dry earth. The baby cried from hunger, and she stopped from time to time to give him water sweetened with piloncillo, the only thing she could offer. Her mind worked tirelessly searching for solutions. She could leave him at the Dominican convent in Tlacolula. She could take him to an indigenous family who might accept him in exchange for money. She could even keep him, pretending he was an abandoned child she had found, raising him as her own, but every option carried dangers, possibilities of being discovered.

At sunset, she reached Tlacochaguaya, a small village with a baroque church with white walls and a central square where ceramics and textiles were sold. Ana Belén knew the place because she had come here years ago with Señora Leonor to buy embroidered tablecloths. She sat under an ash tree to rest and think.

The baby had fallen asleep on her chest. He was beautiful, with long eyelashes and perfect fingers. He did not deserve to die for the sin of his parents. A curious woman approached. Where do you come from, sister? Ana Belén recognized her Zapotec accent. From the Hacienda Santa Cruz. I am taking this child to his family. The woman looked at the baby, and then at Ana Belén, with eyes that had seen too much. There is no family, she simply said. Ana Belén did not answer. The woman sat beside her. My daughter lost a child two months ago. She still has milk. If you need someone to breastfeed him, I can take you. Was it an offer or a trap? Ana Belén did not know, but the baby was hungry, and she had no choice.

She followed the woman to an adobe house on the outskirts of the village. The daughter was young, perhaps 20, with a face marked by recent grief. When she saw the child, her eyes filled with tears. She took him in her arms without asking anything and put him to her breast. The baby began to suck greedily. Ana Belén watched the scene, feeling something she had not felt in years. Hope.

How much? the pragmatic mother asked. Ana Belén took 20 pesos from the pouch for his care for a year. After that, I will come back with more. It was a lie, but necessary. The woman took the money and tucked it into her blouse. What is his name? He does not have a name yet, Ana Belén said. The young woman who was nursing the child spoke for the first time. I will call him Gabriel, after the angel who announces the impossible.

Ana Belén returned to the Hacienda Santa Cruz three days later. She had taken long detours, stopping in different villages, building a credible story of a long journey to hand over the child. When she arrived, she found the house in official mourning. Black cloths hung in the windows. Fray Domingo had said a mass for the soul of the deceased child. Doña Leonor remained in her room, receiving visits from the few Spanish families in the region who came to express their condolences. No one asked for details. Infant death was so common that an explanation seemed unnecessary.

Don Rafael Villarreal arrived a week later, covered in dust from the journey, irritated at having had to interrupt his business in the capital. When he learned of the dead child, he showed disappointment, but no pain. Another lost son, he said, God has his reasons. Doña Leonor wept genuinely, but not for the reasons her husband imagined.

Ana Belén observed them during meals, during conversations in the corridor, during the moments when Don Rafael reviewed the hacienda’s accounts with Jacinto. The foreman kept his gaze lowered, answered in monosyllables, avoiding being alone with the Señora. The tension was like a rope that tightened a little more each day, threatening to snap.

Months passed. Autumn brought the first rains, winter dried the fields, spring made the bougainvillea trees that climbed the hacienda walls bloom. Ana Belén continued her duties, washing clothes, cooking, caring for the chicken coop. Once a month, she invented an excuse to go to Tlacochaguaya. She brought money to the family caring for Gabriel. She watched him grow strong and healthy. The child was already 8 months old. He crawled, laughed when she made faces. The young woman who nursed him treated him as her own. He is a good boy, she said. God bless you for bringing him.

But secrets, like debts, always demand their price. In May 1788, an unexpected visitor arrived at the hacienda, Don Rodrigo Villarreal, Don Rafael’s younger brother, who had lived for ten years in Guatemala managing indigo plantations. He was returning to New Spain to claim his share of the paternal inheritance. He was an observant man with a sharp gaze, capable of noticing inconsistencies where others only saw the surface.

At the welcome dinner, he inquired about the dead child. When exactly was he born? Last August, Doña Leonor replied, her voice trembling. And how long did he live? Barely a few days, Don Rafael interjected, he was not even baptized. Don Rodrigo nodded, but his eyes drifted to Ana Belén, who was serving the wine. You were present at the birth, he said. It was not a question. Ana Belén nodded. And what did you see? The question hung in the air like a suspended knife. Ana Belén felt the eyes of everyone on her. I saw a child who could not breathe well, Señor. He was born blue, struggled for three days, then went out like a candle. It was a technical lie and an emotional truth at the same time.

Don Rodrigo did not seem convinced, but he did not insist. During his visit, he asked strange questions, checked old documents, spoke with the workers. One afternoon, Ana Belén saw him talking to Jacinto near the stables. She did not hear what they said, but she saw the foreman grow tense, saw Don Rodrigo point toward the big house, his gestures conveying accusation.

That night, Jacinto sought out Ana Belén in the kitchen. Don Rodrigo suspects something, he said. He asked me if I noticed anything unusual about the Señora during the pregnancy, if I saw her speaking privately with anyone. And what did you tell him? That I was only attending to my duties. But he did not believe me. He has that way of looking that reads your thoughts.

The following week, Don Rodrigo announced that he would stay on the hacienda indefinitely. He had plans to modernize the cochineal production, bring in new techniques from Guatemala, and increase profits. Don Rafael accepted his brother’s help, unaware that he was inviting his own ruin. For Don Rodrigo had not come just for business. He had come because he had received an anonymous letter in Guatemala, a letter that spoke of a child who had not died, of an adultery hidden under false mourning, of a slave who knew too much.

Who had written that letter? Ana Belén never knew for sure. She suspected the majordomo, an old Spaniard named Melchor who had been on the hacienda for 40 years and had seen Don Rafael and his brother grow up. Melchor was a man of old loyalties, who believed the Villarreal family deserved to know the truth about their blood. Or perhaps it was the chaplain, Fray Domingo, who had unwittingly heard something in confession and decided to comply with a moral duty higher than the sacramental secret. Or maybe it was one of the maids, envious of Ana Belén’s power, who wanted to see her fall. On the haciendas, walls have ears and ears have tongues.

Don Rodrigo began his investigation subtly, checking the parish registers, speaking with the doctor who occasionally visited the hacienda, questioning the midwives in the region, offering money, threatening punishments, promising protection. Slowly, he built a case. He did not have definitive proof, but he had enough loose ends to weave a rope.

One June afternoon, while the family was having dinner, Don Rodrigo dropped his bomb with calculated precision. Brother, he said, I believe you need to know something about the child who died last year, or rather, about the child who did not die. The silence that followed was absolute. Don Rafael put down his fork. What are you implying? I am not implying, I am asserting, Don Rodrigo replied. Your wife gave birth to a live child, a child who was handed over to a family in Tlacochaguaya, a child whose skin revealed an inconvenient truth. Doña Leonor stood up, white as the tablecloth. Are you mad? I am informed, Don Rodrigo corrected, and I suggest we go together to look for that child. If he does not exist, I will apologize. If he does exist, we will have a necessary conversation about honor and consequences.

The next day, a delegation left for Tlacochaguaya. It included Don Rafael, Don Rodrigo, Fray Domingo, Jacinto, and Ana Belén. No one spoke during the journey. Ana Belén knew her life hung by a thread. If they found Gabriel, everything would collapse. If they did not find him, Don Rodrigo would look like a liar, but the suspicions would remain. She prayed silently, not knowing which saint to turn to. To the saint of innocents, to the saint of pious liars, to the saint of lost causes.

When they arrived at the village, Ana Belén led them to the adobe house, but the house was empty, completely empty. There was no furniture, no people, only bare walls and a swept earth floor. The neighbors said the family had left two months earlier for the coast, they had received money from a relative and decided to start a new life in Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca. No one knew exactly where.

Don Rodrigo questioned half a dozen people. All said the same thing. Family gone, child included, unknown destination. On the way back, Don Rafael did not look at his wife. Don Rodrigo rode ahead, frustrated but not defeated. Ana Belén breathed heavily, knowing she had won time, but not the war, for the truth was that she had emptied the house. Two weeks earlier, knowing Don Rodrigo was asking questions, she had taken the 30 pesos she had left, gone to Tlacochaguaya, and convinced the family to leave immediately. She had given them the money, explained the danger, told them to go far away and never return. The young woman who nursed Gabriel had cried, but she understood. We will protect the child, she had promised, as if he were our own.

The following months were one of contained storm. Don Rafael, though without definitive proof, began to distance himself from his wife. They no longer shared the bed, barely spoke during meals. Don Rodrigo returned to Guatemala after months of fruitless searching, but he had sown the seed of doubt. Jacinto was demoted from foreman to simple field worker, without official explanation, but with a clear message. Ana Belén continued her work, but she felt Don Rafael’s eyes on her every time she entered a room. The master knew she knew something, but did not dare question her directly, as that would mean lending credibility to his brother’s accusations.

In September 1790, two years after Gabriel’s birth, news reached New Spain that King Charles IV had ascended the throne. With him came rumors of reforms, of changes to the laws concerning slavery, of pressure from Europe to moderate colonial abuses. They were only rumors, but they circulated intensely on the haciendas. The slaves spoke quietly of possible future freedoms. The masters reacted with greater harshness, fearful of losing control. Social tension grew like a river overflowing its banks before a storm.

One evening in November, Doña Leonor sent for Ana Belén to come to her room. She was sitting by the window, looking at the full moon that illuminated the valley. Where is my son? she asked bluntly. Ana Belén had waited two years for that question. Far away, safe, alive. Yes. Do you know exactly where? No. I told them not to tell me. It is safer that way. Doña Leonor closed her eyes. Sometimes I dream of him, of his dark skin, of his eyes. I wake up crying. Don Rafael no longer touches me. I believe he hates me, even though he cannot prove it. He hates you because he suspects, Señora, but as long as there is no proof, he cannot act without destroying his own reputation. And if I die, Doña Leonor asked, what will happen to the child? Who will know he is mine? Ana Belén had no answer. The Señora continued: I want you to write something, a statement signed by me, witnessed by you, something that explains the truth, that tells Gabriel who his mother was, not for now, for the future, for when we are all dead and the scandal no longer matters.

It was an impossible and necessary request. Ana Belén, who had secretly learned to read and write during her years on the hacienda, took a quill and paper. Under Doña Leonor’s dictation, she wrote a full confession. The adultery with Jacinto, the birth of the child, the decision to hide him, Ana Belén’s role as savior. The Señora signed with a trembling hand. Ana Belén tucked the paper into a wooden box that she hid beneath the floorboards of her small servant’s room.

In 1794, Don Rafael fell ill with a fever. The doctors said it was malaria contracted during a trip to the coast of Veracruz. He died in delirium in December, calling out for his dead mother. Doña Leonor inherited the entire hacienda, with no recognized children, becoming one of the few female landowners in the region. Don Rodrigo tried to contest the will, arguing his brother had been poisoned by his adulterous wife, but without concrete evidence, the case collapsed. The Widow Villarreal continued to manage Santa Cruz with the help of new employees brought from Puebla.

Ana Belén grew old with the hacienda. Her hair turned gray, her back hunched, but her spirit remained alert. Once a year, she sent money through intermediaries to the coast, where she believed Gabriel and his adoptive family lived. She never received confirmation. She never knew if the money arrived, but she continued to send it as an act of faith.

In 1810, when the priest Hidalgo raised the banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the War of Independence began, Ana Belén was 63 years old. The Hacienda Santa Cruz was looted twice by insurgents seeking weapons and money. Doña Leonor died in 1812 during a rebel attack, hit by a stray bullet in her own home. Ana Belén, finally free by the decree of abolition proclaimed by Hidalgo, remained in the ruins of the hacienda along with other former slaves who had nowhere to go.

In 1821, when Mexico declared its independence, she was a 74-year-old woman who spent her days sitting under the ash tree in the courtyard, remembering. Sometimes travelers came, merchants, demobilized soldiers. Some stayed to hear her stories of the times of the Viceroyalty, of the great families that fell, of the secrets that died with their masters.

One afternoon in September of that same year, a man of light brown skin, about 33 years old, arrived at the hacienda asking for Ana Belén. He carried a small wooden box and an old, time-yellowed letter. The letter was signed by Doña Leonor Villarreal. The man said his name was Gabriel. He had been raised on the coast, the adopted son of a Zapotec family who had told him the truth about his origins on his 21st birthday. It had taken him years to decide to search, but finally, he had come. He wanted to know his entire story.

Ana Belén looked at him for a long time, searching in his features for the traces of Jacinto and Doña Leonor. They were there, mixed, fused in a face that was all and none. She told him everything, from the birth to the escape, from the lies to the truths, from the fear to the hope. Gabriel listened without interrupting, and when she finished, he took her wrinkled hand in his and said, Thank you for saving me and for preserving the memory.

Ana Belén died three months later, in December 1821, surrounded by the few people who still lived in the remnants of the Hacienda Santa Cruz. Gabriel was present, and when they buried her under the ash tree she had loved so much, he placed a stone with a simple inscription he had carved himself on her grave. Ana Belén, slave who saw freedom arise where all saw only chains.

News

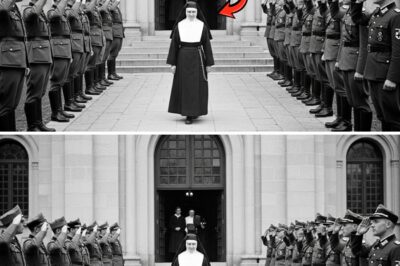

She murdered 52 Nazis with a hollow Bible – the deadliest nun of World War II

An excavated Bible rests on a wooden table. The pages are cut out. Inside, a German Luger pistol and three…

The Pine Ridge Sisters Were Found in 1974 — What They Revealed Had Been Buried for Generations

In the winter of 1974, two elderly women were discovered on a farm outside Pine Ridge, South Dakota. They had…

The farmer bought a huge slave girl for 7 cents… Nobody suspected what he would do.

Everyone laughed when he paid only 7 centavos for the woman almost 2 meters tall, who was deemed useless by…

The Hollowridge twins were found in 1968—their stories didn’t match the evidence.

In the winter of 1968, two children emerged from the Appalachian wilderness, having been missing for 11 years. They were…

End of content

No more pages to load