For nearly three decades, the feud between Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. has been the defining tragedy of hip-hop. It’s a story we’ve been told was inevitable, a fated clash of titans, an East Coast vs. West Coast war fueled by genuine, murderous hatred.

According to Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson, that entire narrative is a lie.

In a stunning revelation, 50 Cent, a man whose own life was forged in a strikingly similar fire of violence and industry beef, has pulled back the curtain on this mythology. He argues the hate was “overhyped,” the beef “manufactured,” and the real villains were not the two men on the mic, but the “record label executives” who saw a personal tragedy as a multi-million dollar marketing opportunity.

The truth, 50 Cent insists, is far more tragic than a simple feud. It’s the story of a brotherhood, a profound misunderstanding, and a calculated industry betrayal that led two kings to their graves. 50 Cent’s perspective is not just commentary; it’s the testimony of a survivor, a man who “studied their deaths like a street general” and learned the lessons that allowed him to live.

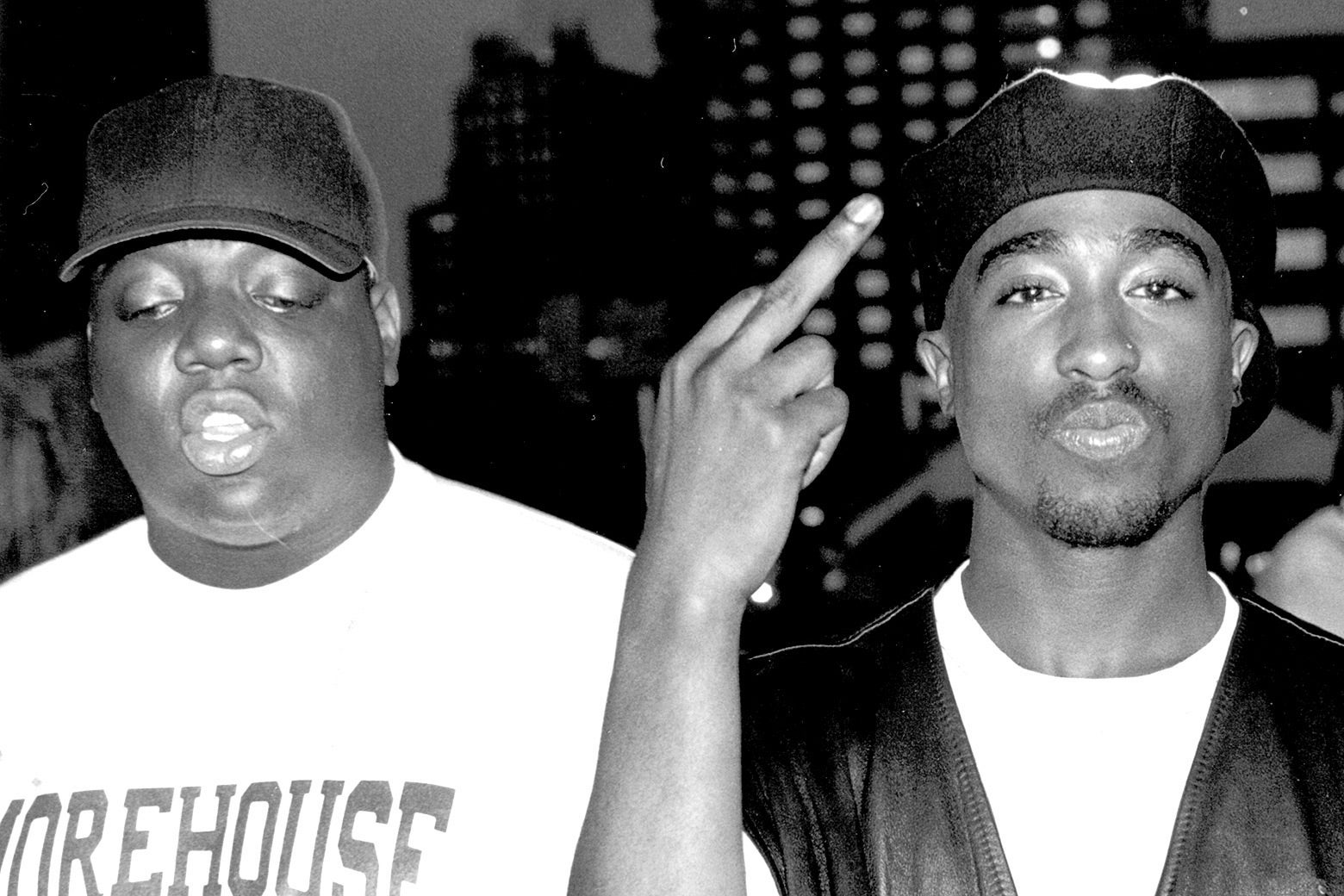

To understand the lie, you must first understand the truth of 1993. Before the war, there was a brotherhood. Tupac Shakur was already a platinum-selling superstar, a magnetic force in music and film. Christopher Wallace was just “Biggie Smalls,” a “hungry up-and-coming spitter from Brooklyn” still pushing mixtapes on the block.

When they met, Tupac didn’t just shake his hand. He “welcomed this Brooklyn cat into his crib with open arms,” showing him “mad love.” As the source material details, this was not a casual industry acquaintance. Tupac, the established star, let the unknown Biggie “crash on his couch like they was blood.”

More than a place to sleep, Tupac gave Biggie the keys to the kingdom. He provided a “blueprint for success that was absolutely revolutionary for that time.” Recognizing Biggie’s raw talent, Tupac offered him the formula that would define his career and change pop music: “Don’t rap for men, rap for women on the singles. You can do the raw hip-hop stuff on the album.”

This was the strategy that created the dual-persona of Biggie Smalls: the crossover radio king of “Big Poppa” and the gritty street narrator of “Ready to Die.” Tupac didn’t just mentor him; he handed him the crown. In an act of true selflessness, Tupac even advised Biggie against signing with him, pushing him toward a young, ambitious executive named Sean “Puffy” Combs. “Nah, stay with Puff,” Tupac advised. “He will make you a star.”

This bond was public. They freestyled together on stage at the Budweiser Superfest in 1993. Busta Rhymes, a witness to their friendship, later revealed that Biggie once recorded a scathing Tupac diss but couldn’t bring himself to release it. He “muted the lines… out of respect for what they had.”

This was the reality 50 Cent wants the world to see. It wasn’t hate. It was family.

So, what shattered this brotherhood? According to 50 Cent, it wasn’t a genuine street beef. If it were, he argues, “they would have handled that in the streets immediately… They wouldn’t have been making diss records.” 50 Cent knows the difference. He survived nine gunshots. He understands that real beef and recorded “beef” are two entirely different worlds.

The breaking point was a single, paranoid moment built on a foundation of betrayal. On November 30, 1994, Tupac arrived at Quad Recording Studios in Times Square. As he entered the lobby, he was ambushed, robbed of $35,000 in jewelry, and shot five times. Bleeding and “barely clinging to life,” Tupac was wheeled out on a stretcher. As he looked up, he saw Biggie and Puffy in the studio, “looking like they wasn’t even shook… seemingly unfased.”

In that moment of pain and confusion, Tupac’s world collapsed. He didn’t see two friends; he saw two traitors. This paranoia was catastrophically amplified when, the very next day, he was convicted on an unrelated sexual molestation charge. As Tupac sat in a jail cell at Riker’s Island, the “seed of doubt” festered. He told Vibe magazine, “I thought my closest homies would be the ones to set me up.”

The tragedy is that he was wrong. Biggie, desperate to clear his name, “visited Tupac in Riker’s Island” to convince him he had nothing to do with it. But by then, the paranoia had “taken root so deeply that no amount of denial… could uproot it.”

This is where 50 Cent points his finger at the “real villains.” The “industry snakes and vultures” saw this personal, tragic misunderstanding and turned it into a “full-scale coastal war” for profit.

Leading the charge, in 50’s analysis, were the two puppet masters: Suge Knight and Puffy.

Suge Knight, already in a business feud with Diddy, swooped in “like a savior.” He posted Tupac’s $1.4 million bail, but it wasn’t an act of love; it was an acquisition. He “saw Tupac as the perfect weapon to use against Bad Boy Records.” At the 1995 Source Awards, Suge’s infamous speech—“Any artist out there that wanna be an artist and stay a star… Come to Death Row!”—was a direct shot at Diddy. He was “pouring gasoline on a fire” and using Tupac’s pain as the match.

On the other side, Puffy made a move that was, at best, catastrophically tone-deaf. Just months after Tupac was nearly killed, Bad Boy released “Who Shot Ya?” as a B-side. Though the label swore it was recorded earlier, the timing was “impossible for Tupac to see… as anything other than a direct taunt.”

Blinded by paranoia and fueled by Suge Knight, Tupac declared “total war” with “Hit ‘Em Up,” a track so vicious it scorched the earth. Crucially, as 50 Cent points out, Biggie “remained mostly silent publicly.” He refused to engage at the same level of vitriol.

In his very last interview, just days before his own murder, Biggie finally explained his perspective, validating 50 Cent’s entire thesis. “Coastal war? I never hated nobody from the West Coast,” Biggie said. “It was a personal beef… I kind of recognize the power that me and Tupac had… to wage an East Coast West Coast beef… I got to take his place and my place… and just squash it.”

He wanted peace. But it was too late. The machine they had set in motion, the machine that 50 Cent now holds responsible, had grown too powerful to stop.

50 Cent’s analysis is so potent because he learned the lessons they didn’t. He “studied Tupac and Biggie’s deaths” and recognized they both died from “wounds to their torsos that would have been prevented by body armor.” 50 Cent wore his vest. He survived his nine shots. He lived to see the game for what it was.

Today, 50 Cent’s accusations have become terrifyingly direct. Amid Diddy’s ongoing federal charges for sex trafficking and racketeering, 50 has bluntly accused him of “orchestrating Tupac’s death.” This connects the manufactured beef of the ’90s directly to the alleged real-world criminality 50 has pointed at all along.

The ultimate proof of 50’s theory, however, may come from Tupac himself. In a moment of clarity, Pac defined the “beef” in his own words. “It was never a beef. It’s only a difference in opinion,” Tupac said. “That’s like me being mad at my little brother ‘cuz he get cash… I’m just mad at my little brother when he don’t respect me.”

It wasn’t hate. It was a “big brother” feeling betrayed by a “little brother” he loved. That single, painful misunderstanding was all the industry needed. They lit the fuse, sold the tickets, and counted the money as the two biggest stars in the world, and the two brothers who started it all, went up in flames.

News

The Billion-Dollar Exodus: Stephen A. Smith Reveals Shocking Saudi Offer to Caitlin Clark That Could Destroy the WNBA

In a development that threatens to upend the entire structure of women’s professional sports, a seismic rumor has emerged that…

The $20 Million Rejection: Caitlin Clark’s Power Move Sparks Chaos for Stephanie White and WNBA Front Offices

In a professional sports landscape defined by athletes chasing the biggest paycheck, Caitlin Clark has done the unthinkable: she has…

The Gamble of a Lifetime: Inside the WNBA Players’ Shocking Rejection of a Million-Dollar “Dream Deal” and the Looming Lockout

In a year defined by unprecedented growth and shattering records, the WNBA has suddenly found itself on the precipice of…

Power Shift: A’ja Wilson’s “Meltdown” Exposed as Forbes Crowns Caitlin Clark the New Queen of Sports Economy

In the high-stakes world of professional sports, numbers rarely lie. They tell stories of dominance, influence, and market value that…

The New Guard Arrives: Inside the Shocking Exclusion of A’ja Wilson and the Coronation of Caitlin Clark as Team USA’s Future

In a move that has sent shockwaves through the basketball world, USA Basketball appears to be orchestrating one of the…

50 Cent vs. Diddy: The “Octopus” Documentary, The “Shopping” Offer, and The Industry Titans Allegedly Trying to Stop It

Los Angeles, CA – If you thought the feud between Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson and Sean “Diddy” Combs was just…

End of content

No more pages to load