In the annals of West Coast hip-hop, where legends were born and empires crumbled under the weight of their own ambition, one name echoes with a blend of fear and respect: Heron Verdell Palmer. Known on the streets as Goldie or even “Mr. 17,” Palmer was no ordinary figure in the notorious Death Row Records saga. He was the quiet storm, the unyielding protector, the man whose loyalty was as fierce as his reputation, a reputation whispered to include seventeen bodies. His story, deeply stitched into the fabric of Compton’s gang landscape and the tumultuous rise and fall of Death Row, offers a raw, unfiltered look at the cost of power, the complexities of street allegiance, and the surprising connections that bound together some of music’s biggest stars.

Heron Palmer emerged from the crucible of Compton in 1962, a city already simmering with tension that would soon ignite into the infamous gang wars of the Bloods and Crips. From a young age, Palmer was immersed in the harsh realities of street life—armed robberies, drug dealing, and unrelenting gang violence. This wasn’t a phase; it was his world, and he navigated it with a shrewd intelligence that belied his fearsome demeanor. Tall, powerfully built, and radiating an aura of unwavering resolve, Palmer was known as a man who simply did not back down. “He had no fear in his blood,” the streets would attest, and they weren’t wrong.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, Palmer’s path converged with that of Marion “Suge” Knight, the imposing co-founder of Death Row Records. Suge, a former football player with a brief stint in the NFL, was building a music empire that would redefine hip-hop. But this wasn’t just about platinum records; it was about street power, and Suge knew that to dominate the music industry, he needed the unwavering muscle of the streets. Heron Palmer became an indispensable part of Suge’s inner circle, officially hired for security, but unofficially serving as the ultimate “fixer”—the man to call when words failed and raw force was required.

Death Row Records, co-founded in 1991 by Dr. Dre, Suge Knight, Dick Griffy, and Michael “Harry-O” Harris, quickly became a titan. With groundbreaking albums like Dr. Dre’s The Chronic and Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle, the label ushered in the G-funk era, capturing the world’s attention. When Tupac Shakur joined in 1995, delivering masterpieces like All Eyez on Me and The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, Death Row cemented its status as an unstoppable force, raking in over $100 million annually at its peak. Yet, behind the glitz and glamour, Suge Knight ensured that the label remained tethered to its street roots, staffing its ranks with members of the Mob Pyru Bloods—men like Wardell “Poochie” Fouse, Jake “Big Jake” Robles, Trayvon “Tree” Lane, Alton “Buntry” McDonald, Henry “Hendog” Smith, and, of course, Heron Palmer. These weren’t just hangers-on; they were enforcers, protectors, and sometimes, the instruments of swift retribution when lines were crossed.

Heron Palmer’s loyalty to Tupac Shakur became legendary. In the tumultuous mid-90s, when rap rivalries intensified into outright gang warfare, Palmer stood as Tupac’s unwavering shield. Whether stepping into confrontations or meticulously securing Tupac’s movements, Heron had his back. Their bond extended beyond professional duties, marked by shared moments of talks and laughter—a trust forged in the dangerous crucible of their lives. Tupac himself immortalized Palmer in his song “To Live and Die in L.A.,” a public stamp of respect that resonated deeply within the streets where such recognition was earned, not given.

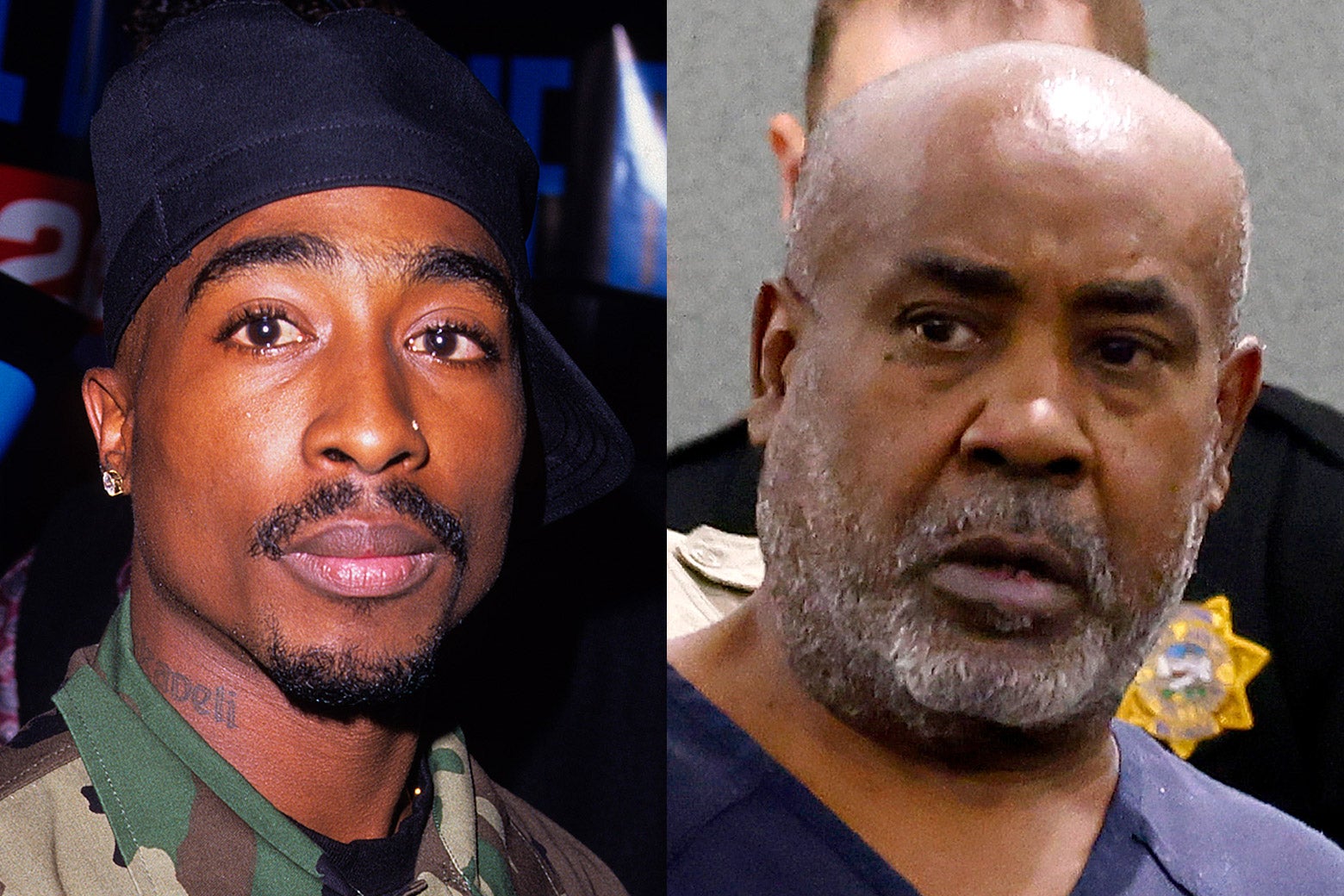

The synergy between the streets and the studio, however, was a double-edged sword. The same ties that fueled Death Row’s power also heralded its demise. The infamous incident on September 7, 1996, at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas encapsulates this volatile blend. After Mike Tyson’s quick victory, Tupac, Suge, and their entourage spotted Orlando “Baby Lane” Anderson, a Southside Compton Crip who had allegedly robbed Trayvon Lane of his Death Row chain months earlier. Without hesitation, Tupac attacked Anderson, with Heron Palmer and other Death Row affiliates quickly joining the fray. This public beatdown, captured on security cameras, was more than just a brawl; it was a declaration of war, an act that would irrevocably alter the course of hip-hop history.

Hours later, as Suge Knight drove Tupac to a performance at Club 662, a white Cadillac pulled alongside their BMW on East Flamingo. Gunfire erupted, hitting Tupac multiple times and grazing Suge. While Heron Palmer’s name doesn’t appear in official reports as a shooter or driver that night, sources close to the label confirm his presence within the convoy, part of the muscle meant to protect Tupac. The chaos that ensued, the desperate rush to the hospital, and Tupac’s subsequent death six days later, deeply affected Palmer. For him, Tupac was more than an artist; he was a brother, and his loss was profoundly personal, fueling a desire for street retribution.

The aftermath plunged Compton into a bloody vortex of retaliation. Shootings between Southside Crips and Mob Pyru members erupted immediately. Informants pointed fingers at Orlando Anderson as Tupac’s killer, intensifying the already boiling gang war. Heron Palmer, Mob Pyru, and Death Row muscle, found himself at the epicenter of this escalating conflict. Yet, despite his “Mr. 17” reputation, Palmer was never reckless. He was patient, calculated, a man whose moves were always deliberate and strategic in a city primed to explode.

Amidst this maelstrom of violence, whispers of a more intimate connection involving Heron Palmer began to circulate: a rumored relationship with the enigmatic R&B superstar, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopez. Left Eye, a fiery and independent spirit, had already achieved global fame as one-third of TLC. By 2001, frustrated with her solo album’s reception and tensions within her group, she boldly reached out to Suge Knight, seeking his help to break free from her record deal. This call soon evolved into a personal connection with Suge, leading her to spend months living near Death Row’s offices. Their relationship was described as intense, passionate, and unpredictable—a volatile mix for two strong personalities.

Yet, it was the unspoken connection with Heron Palmer that adds another layer of intrigue to Left Eye’s Death Row chapter. While never officially confirmed, rumors persisted about a deeper bond between the R&B icon and the feared gang enforcer. In the world of Death Row, where secrets often held more weight than headlines, such whispers carried their own kind of truth. If true, it painted a picture of Left Eye, already a formidable woman, being drawn into the orbit of one of the label’s most dangerous figures, further intertwining her story with the perilous realities of the “Row.” Her audacious spirit, her health-conscious lifestyle, and her confrontational nature, even reportedly attempting to set fire to a bed in Suge’s penthouse after he didn’t come home, showcased a woman who defied control, even from men like Suge Knight.

Heron Palmer’s life, however, was not destined for a peaceful end. Despite his calculated approach and the fierce loyalty he commanded, the currents of Death Row’s internal and external conflicts proved inescapable. Tensions grew between Palmer and other figures in Suge’s circle, notably George “Poochie” Williams, suggesting internal strife within the already fractured empire. For a man who risked his life daily, perceived betrayals, especially regarding unpaid dues, were lethal.

On June 1, 1997, just before sunset, Heron Palmer left a Death Row Records party at Gonzalez Park in Compton. As he drove home, he stopped at a red light. A blue van pulled up behind him, and two men jumped out, unleashing a barrage of gunfire. Heron Palmer, at 30 years old, “Mr. 17,” the man who had stood beside Tupac and handled Death Row’s dirtiest business, was dead.

His murder sent shockwaves through Compton and the already crumbling foundation of Death Row. “When Heron went down, we were all like, ‘Woah, what’s going on here?’” recalled officer Bobby Ladd. “Until that moment, nobody ever had the nerve to take out anyone in Suge’s inner circle.” Palmer was not an easy target; his murder was a chilling message, signaling that even the most protected figures in Death Row were vulnerable. His death ripped away one of the few individuals capable of bridging the gap between the volatile streets and the chaotic music industry without losing credibility.

Years after his murder, the legacy of Heron Palmer endures. People whisper theories about who ordered the hit—personal beef, unpaid debts, or internal power struggles within Death Row. His name consistently resurfaces in discussions about Tupac’s final moments, the history of Mob Pyru, and the untamed era of Death Row. In a cruel twist of fate, Heron’s own son, Christopher, was tragically killed in a gang-related incident at just 17 years old, a number that eerily echoed his father’s infamous street moniker.

Tommy Daugherty, a house engineer who worked with Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and Tupac at Death Row, offered a unique insight into Palmer’s character. Not from the streets himself, Daugherty found an unlikely protector in Palmer. He recalled a bullet-ridden Jeep Cherokee, a casual “You should see what their car looks like,” and then Palmer’s declaration: “Tommy D, I’ve got to tell you something man, I don’t know what it is about you man, but some of the hardest motherfuckers and motherfuckers who don’t even like motherfuckers, them fuckers like you. And Suge said, ‘Make sure nobody fucks with him so you don’t have to worry about shit. If anybody fucks with you, you come and talk to Heron.’” This was more than a compliment; it was a shield in a world where “bodies were dropping constantly,” a testament to Palmer’s discerning loyalty and formidable protection.

Heron Palmer’s story is a profound cautionary tale, a brutal illustration of how the pursuit of power and fame, when intertwined with the unforgiving codes of the street, can lead to inevitable tragedy. He was a man of contradictions: feared yet trusted, capable of quelling a brawl or initiating one, a silent enforcer whose presence spoke volumes. His life, marked by unwavering loyalty to Tupac and a rumored, tender connection to Left Eye, yet ultimately consumed by the violence he embodied, remains an unforgettable chapter in the tumultuous narrative of Death Row Records, a stark reminder that in the game of the streets, nobody lasts forever.

News

💥 “ENOUGH IS ENOUGH!” — Britain ERUPTS as Explosive Video of Beach Sabotage Sparks National Outrage

SHOCKING FOOTAGE FROM FRANCE “ENOUGH REALLY MEANS ENOUGH.” New clips from the French coast are igniting a firestorm in Britain…

REFORM ROLLS TO HUGE WIN RIVAL GRABS THREE AS LABOUR HITS ROCK BOTTOM!

Reform pulls off huge by-election win but rival snatches triple victory as Labour flounders WATCH: Francesca O’Brien calls for GB…

BRITAIN ERUPTS: Public Anger Hits BREAKING POINT as Westminster Stays Silent 😡

Britons have been filming themselves travelling to beaches in France and ‘destroying’ small boats – gaining thousands of views in…

COUNTRYSIDE UPRISING ERUPTS: Police Ban Farmers’ March — But 10,000 Tractors STILL Roll Toward London in Defiant Show of Strength!

A farmer has warned the Labour Government will need “the army” to stop the tractors descending on Westminster ahead of the Budget….

BREAKING: Richard Madeley COLLAPSES IN DESPAIR Live on GMB — Viewers ROAR “ENOUGH!”

Moment GMB’s Richard Madeley flops head on desk as Labour minister leaves fans fuming Transport Secretary Heidi Alexander left Good…

ROYAL BOMBSHELL: Prince William and Princess Catherine Reveal MAJOR Shake-Up Before Sandringham Walk 😳 The Christmas tradition Britain counts on every year is suddenly uncertain — and the reason behind it has stunned even long-time palace staff. Something has clearly changed inside the Wales household… but why now?

The royals’ long-standing Christmas trestle-table ritual that Prince William wants to axe It has been a long-standing, if light-hearted, tradition…

End of content

No more pages to load