In 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, Louisiana simmered with tensions that went far beyond politics. In the Mississippi Delta, where hot steam carried the sweet aroma of cotton mixed with the acrid smell of human sweat, small plantations struggled to survive the economic instability that plagued the South.

Just a few miles from New Orleans, where slave auctions took place daily in public squares, Delaney Plantation stretched across a modest 200 acres of fertile land. Unlike the grand estates that dominated the region, this was home to a family desperately clinging to their place in southern society. Clement Delaney was no cotton baron.

He was a man of limited means, owner of only 15 slaves and a two-story wooden house that already showed signs of deterioration. But what happened within those walls between 1860 and 1863 would reveal a face of slavery that few dared to imagine. This is one of the most disturbing stories I’ve ever heard about the hidden horrors of the antibbellum south.

A story that shows how desperation can transform a family man into something far worse than a monster. Before we continue, tell me in the comments. Where are you watching from? And if this is your first time here at Legacy of Fear, don’t forget to subscribe to the channel for more stories that will keep you awake at night. Delaney Plantation had known better days.

Clement Delaney at 45 was a man of medium stature with brown hair already graying and hands calloused by work. Unlike the great landowners who rarely dirtied their hands, Clement worked side by side with his slaves in the cotton fields, a necessity he tried to disguise as choice. His wife Joanna, at 38, had aged prematurely.

Her blonde hair, once brilliant, now hung lifeless around a face marked by constant worry. She had given birth to four children, but only three survived. Arlene, 19, Carolyn, 17, and Freda, the youngest at just 15. The three Delaney daughters were considered beautiful by the standards of the time.

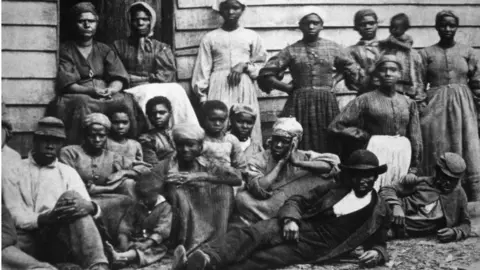

Arlene possessed her mother’s golden hair and penetrating blue eyes. Caroline had inherited more delicate features with brown hair and a fragile constitution. Freda, the youngest, combined her sister’s beauty with a vivacity that had not yet been completely suffocated by the realities of adult life. The plantation operated with 15 slaves, eight men and seven women.

Among them was Tobias, a strong man of about 30 who served as informal overseer, and Laya, a 25-year-old woman who worked in the big house. Most had been born on the property, creating a complex family dynamic that Clement would soon learn to exploit. Financial troubles began in 1858 when a plague devastated much of the cotton plantation.

The harvest yielded less than half of what was expected, forcing him to take loans with exorbitant interest from New Orleans merchants. To make matters worse, Clement developed a gambling addiction that consumed any extra money. The nights when Clement disappeared to card tables became more frequent.

He would return in the early morning hours, often with less money than he had taken, his face marked by frustration and drink. During these absences, Joanna often found him muttering alone in his office, calculating and recalculating numbers on pieces of paper that he quickly hid when she approached. In 1859, the situation became unsustainable. Creditors began appearing at the plantation, well-dressed men from New Orleans who spoke in legal terms about debt execution and property confiscation.

Clement was forced to sell three of his most valuable slaves, a decision that humiliated him deeply before the local community. The sale of the slaves brought temporary relief, but also revealed something disturbing in Clement’s behavior. During negotiations, he demonstrated a calculating coldness that shocked even experienced buyers. He examined the teeth, muscles, and scars of his slaves as if they were cattle.

openly discussing their reproductive capabilities and market value. Dr. Ruben McCormick, the local physician who occasionally visited the plantation, noticed changes in Clement’s behavior during this period. The man who had once been reserved but cordial became increasingly isolated and obsessive. McCormick observed that Clement began asking strange questions about fertility, pregnancy, and the laws governing the legal status of slave children.

Clemens conversations with other slave owners also changed in tone. He began showing excessive interest in the more sorted aspects of human trafficking, asking questions about breeding farms and methods to maximize the productivity of female slaves. These comments caused discomfort even among men accustomed to the brutality of slavery.

Sheriff Peter Mullins, who had known Clement for years, noticed that the man began avoiding eye contact during his occasional visits to the plantation. Mullins attributed this to financial embarrassment. But there was something deeper in Clement’s behavioral change, a fertive quality that suggested thoughts that shouldn’t be shared.

During the winter of 1859, Clement spent long hours locked in his office, studying legal documents and slave codes. Joanna occasionally found him hunched over borrowed law books, making notes on pieces of paper that he quickly hid when she entered the room. He had acquired several volumes on property law and inheritance rights, material that seemed inappropriate for a simple cotton farmer. The atmosphere in the big house began to change subtly.

The daughters noticed that their father observed them differently with an evaluative gaze that made them feel uncomfortable. Arlene commented to her mother that she felt as if she were being examined, though she couldn’t explain exactly what she meant by that. Laya also noticed changes in Clement’s behavior.

He began asking questions about her health, age, and reproductive history that seemed inappropriate, even for a slave owner. She noticed that he paid special attention to the younger slave women, watching them work with an intensity that made her uneasy. Family meals became tense events with Clement often lost in thought.

Responding to conversation attempts with grunts or vague comments. Joanna tried to maintain normaly but felt a growing anxiety she couldn’t fully explain. She began to notice that Clement took notes during meals observing his daughter’s eating habits and general health with attention that seemed more clinical than paternal.

In January 1860, Clement made a mysterious trip to New Orleans that lasted 3 days. When he returned, he brought with him a leather briefcase containing documents that he carefully stored in his office. He had also established contact with a man known only as Borar, whom Clement vaguely described as someone who could help with complex legal matters.

The spring of 1860 brought a promising harvest, but also marked the beginning of more dramatic changes in Clement’s behavior. He began reorganizing the slave quarters, separating men and women more rigidly, and implementing new regulations that seemed to have no clear purpose. The Delaney daughters noticed that their father began restricting their social activities, cancelling visits to neighboring families, and discouraging visitors.

He claimed concerns about security and growing political tension, but his explanations seemed forced and inadequate. Dr. McCormick made his last social visit to the plantation in April 1860. He would later describe the atmosphere as strangely oppressive, noting that the family seemed to be under some kind of stress that went beyond known financial difficulties. During this visit, McCormick observed that Clement made disturbing comments about the efficiency of certain plantations in maximizing their human resources. The doctor was particularly uncomfortable when Clement asked about methods for determining the

fertility of young women and the risks associated with frequent pregnancies. Sheriff Mullins made his last official visit to the plantation in May 1860, investigating reports of runaway slaves in the region. He noticed that the Delaney plantation slave seemed more submissive and fearful than normal, avoiding eye contact and responding to questions with nervous monosyllables.

Mullins also observed that Clement had installed new bolts and locks on several doors of the big house, a measure he justified as a precaution against possible slave revolts. However, the location of some of these locks suggested they were designed to keep people in, not out. The summer of 1860 marked the point of no return for Clement Delaney.

Financial pressures combined with his growing obsession with desperate solutions led him to make a decision that would transform his family into victims of his own greed and depravity. In June 1860, Clement Delaney had become a man consumed by an idea that grew in his mind like cancer. During his obsessive research into slavery laws, he had discovered a legal doctrine dating back to the earliest days of American colonization. Partus sequentum.

This law established that a child’s condition followed that of the mother. If the mother was a slave, the child would be born a slave regardless of paternity. The perverse genius of Clement’s plan lay in his understanding of a legal loophole. The children of his own daughters being born to free mothers would technically be free by law.

But with falsified documentation, these babies could be registered as children of slaves, making them sellable property. It was a monstrous distortion of the law that would transform his own grandchildren into merchandise. During his trips to New Orleans, Clement had established contact with Bogard, a forger who operated in the shadowy alleys of the French Quarter.

This man, whose real name was never revealed, specialized in creating birth certificates, baptismal certificates, and property records that could withstand casual scrutiny from local authorities. Bogard operated from a small office above a tavern where he also offered forgery services for manumission papers and travel documents for runaway slaves.

A dangerous but extremely lucrative business for $50 per document, a substantial sum at the time. He could obtain birth certificates that would attribute the maternity of any child born on the plantation to his slaves, ensuring these babies could be legally sold. Clement began implementing his plan with the meticulousness of a businessman planning an expansion.

He completely reorganized the slave quarters, creating what he called special rooms, small isolated cabins where reproductions would occur under his direct supervision. The first phase of the plan involved careful selection of male slaves who would be used as breeders. Clement chose Tobias and two other young strong men, basing his decision on criteria that included physical health, docsile temperament, and disturbingly physical characteristics he considered commercially desirable in their future offspring. Female slaves were also subjected to degrading evaluation.

Clement personally examined Laya and other women, checking their reproductive health with clinical coldness that left them traumatized. He made detailed notes about their menstrual cycles, previous pregnancy history, and estimated ability to produce quality products. But the most shocking part of Clement’s plan involved his own daughters, Arlene, Carolyn, and Freda would be forced to participate in the breeding scheme, generating children who would be immediately separated from them and registered as slave children. Clement

rationalized this monstrous decision as a necessary sacrifice to save the plantation and maintain the family’s status. To implement this phase of the plan, Clement began making subtle changes to the domestic routine. He installed special locks on his daughter’s rooms, claiming security concerns.

In reality, these locks were designed to prevent them from escaping when the time came to fulfill their role in the scheme. Clement also began administering to his daughters a mixture of herbs he obtained from a local healer named Marie, claiming it was to strengthen their feminine health.

In fact, this mixture contained substances intended to regulate their menstrual cycles and increase their chances of conception when the appropriate time came. The healer didn’t suspect the true purpose of the herb she provided, believing Clement was genuinely concerned about his daughter’s health. Psychological manipulation was as important as physical.

Clement began isolating his daughters from the outside world, cancelling social visits, and prohibiting correspondence with friends. He gradually conditioned them to accept increasing restrictions on their freedoms, psychologically preparing them for the total submission his plan would require.

Joanna began noticing disturbing changes in her husband’s behavior toward their daughters. He watched them with disturbing intensity, making comments about their maturity and development that left her deeply uncomfortable. When she tried to question these observations, Clement dismissed her with irritation, claiming she was being hysterical and imagining things.

In July 1860, Clement made another trip to New Orleans, this time returning with basic medical supplies and manuals on childirth and infant care. He claimed he was preparing for the possibility of not being able to call Dr. McCormick during emergencies, but the quantity and specificity of the materials suggested preparation for multiple births. Clement also established contact with slave traders in New Orleans, inquiring about current prices for babies and small children.

He discovered that healthy babies could be sold for $200 to $300 each, depending on their appearance and perceived health. Children of more European appearance commanded higher prices, a fact that influenced his selection of breeders. The logistics of the plan required precise timing. Clement calculated that with five women, his three daughters and two slaves producing babies at staggered intervals, he could generate a constant flow of products for sale.

He estimated that each woman could produce a baby every 15 to 18 months, resulting in two to three annual sales. To maintain secrecy, Clement planned to conduct sales through intermediaries in distant markets. The babies would be transported to New Orleans or other cities by traders who didn’t ask questions, ensuring no connection could be traced back to Delaney Plantation.

He established contact with a man named Jacqu Tibodau, a trader who transported slave babies and children without asking questions about their origin. Clement also prepared explanations for curious neighbors about any unusual activity on the plantation. He planned to claim he was experimenting with modern slave breeding methods to improve productivity, an explanation that would be accepted without question in a society that viewed slaves as property.

Clement’s psychological preparation to implement his plan revealed the depth of his moral degradation. He began seeing his own daughters not as human beings with rights and dignity, but as resources to be exploited for his financial survival. This dehumanization was essential for him to proceed with actions any normal father would consider unthinkable.

In August 1860, Clement began testing his daughter’s obedience with increasingly strange and invasive demands. He demanded they report intimate details about their feminine health, claiming paternal concern. When they hesitated or questioned these demands, he responded with anger and threats of punishment. The atmosphere in the big house became increasingly oppressive.

The Delaney daughters began to feel they were being constantly watched, that every movement was monitored and evaluated. They couldn’t articulate their concerns, but instinctively felt something terrible was approaching. Laya and the other slaves also felt the change in atmosphere.

Clement began treating them with disturbing familiarity, making comments about their bodies and reproductive capabilities that went beyond even the normal degrading standards of slavery. They whispered among themselves about the changes, but didn’t dare express their concerns openly. Dr. McCormick, during a routine medical visit in August, noticed signs of stress in the Delaney daughters.

They seemed paler and more nervous than normal, and Freda, the youngest, showed signs of weight loss, suggesting chronic anxiety. When he tried to question Clement about the girl’s health, he was dismissed with vague responses about normal family tensions. In September 1860, Clement finally decided all preparations were complete.

He had established the necessary contacts, prepared the facilities, psychologically conditioned his victims, and created the justifications he would use to explain any suspicious activity. What would follow would be one of the most systematic campaigns of abuse and exploitation ever perpetrated within the confines of a single family.

Clement’s plan was about to be implemented, transforming Delaney Plantation from a home into a factory of horror where his own children and grandchildren would become commodities in his desperate scheme for financial survival. If you’re enjoying this disturbing investigation, don’t forget to subscribe to the channel so you don’t miss any details of this story that’s about to get much darker.

In October 1860, Clement Delaney implemented the first phase of his monstrous plan. The transformation of Delaney Plantation into a breeding farm began with a meeting he conducted with his daughters, presented as a discussion about family responsibilities during difficult times. Arlene was the first to be informed about her role in her father’s scheme.

Clement called her to his office on a cold October morning, and with the coldness of a businessman discussing a contract, explained that she would be mated with Tobias to produce children that would help save the plantation. When Arlene reacted with horror and refusal, Clement locked her in her room, informing her she would remain there until she accepted her family responsibility. Arlene’s resistance lasted 3 days.

During this period, Clement allowed only water and small portions of bread while regularly visiting her room to repeat his demands. He alternated between threats of physical violence and emotional appeals about filial duty, gradually breaking her resistance through a combination of deprivation and psychological manipulation.

During these visits, he showed Arlene the family’s debt documents, explaining in detail how they would lose everything if she didn’t cooperate. Caroline and Freda were informed about their roles in the following days. Carolyn, always more emotionally fragile, collapsed immediately, crying uncontrollably and begging her father to reconsider. Freda, despite being the youngest, showed more resistance, declaring she would rather die than participate in her father’s abominable scheme. Clement responded to his daughter’s resistance with calculated cruelty. He informed them that if they

refused to cooperate voluntarily, he would simply force them. He had locked all exits from the big house and posted Tobias and other loyal slaves as guards, ensuring there was no possibility of escape. The first breeding session occurred on a November night in 1860. Clement personally escorted Arlene to one of the specially prepared cabins where Tobias waited.

The slave, clearly uncomfortable with the situation, had been threatened with torture and death if he didn’t follow his owner’s orders. Tobias would later describe that night as the moment his soul died. Forced to participate in an act that violated all his protective instincts, Clement remained outside the cabin throughout the entire process, ensuring his instructions were followed.

He had established a rigid schedule for these sessions based on his calculations about his daughter’s reproductive cycles. The cold efficiency with which he organized these encounters revealed the complete dehumanization of his own daughters in his mind. Joanna, initially kept ignorant of the details of her husband’s plan, began to suspect something terrible was happening when she noticed the deteriorated emotional state of her daughters. Arlene became withdrawn and silent.

Caroline developed frequent panic attacks, and Freda alternated between impotent fury and deep despair. When Joanna tried to question Clement about their daughter’s strange behavior, he brutally informed her about his plan. He explained that the girls were fulfilling their family duty and that any interference on her part would result in severe consequences for the entire family.

Joanna was horrified, but also felt completely powerless to intervene. Clement had made it clear he wouldn’t hesitate to sell all the slaves and abandon the family if she tried to sabotage his plans. slaves. Laya and other women were also integrated into Clement’s breeding scheme. They were subjected to the same degrading process. Forced to mate with selected male slaves at times determined by Clement.

The difference was that being already slaves, their children would automatically be Clement’s property without need for document falsification, Clement kept meticulous records of all reproductive activities on his plantation. He noted mating dates, estimated menstrual cycles, and predicted birth dates in a book he kept locked in his office.

These records revealed the extent of his obsession with maximizing the productivity of his scheme. In December 1860, Arlene confirmed her first pregnancy. Clement received the news with cold satisfaction, immediately calculating the predicted birth date and the child’s potential market value.

He began making preparations for falsifying birth documents, contacting Bogard in New Orleans to provide the necessary paperwork. Carolyn became pregnant in January 1861, followed by Laya in February. Clement was euphoric about the initial success of his plan, seeing this as confirmation that his strategy would work.

He began making plans to expand the scheme, considering the possibility of acquiring more female slaves when his finances improved. Freda resisted longer, but finally became pregnant in March 1861. Her pregnancy was particularly traumatic because she was the youngest and physically least prepared for motherhood. Clement showed little concern for her well-being, focusing only on the potential value of her future child.

During Freda’s pregnancy, he often forced her to perform specific exercises he believed would improve the baby’s quality. The atmosphere at Delaney Plantation became increasingly oppressive as the pregnancies progressed. The Delaney daughters were kept virtually prisoners in the big house, allowed out only under strict supervision.

Clement claimed these restrictions were to protect their valuable cargo, but in reality, they were to prevent any escape attempts or seeking help. Dr. McCormick was called to examine the pregnant women, but Clement carefully controlled these visits.

The doctor was informed that the pregnancies were the result of consensual relationships between the Delaney daughters and slaves. An explanation that while scandalous by the standards of the time, wasn’t technically illegal. To ensure McCormick’s silence, Clement offered the doctor a substantial sum, $50 per visit, well above normal rates. McCormick, facing his own financial difficulties, accepted the arrangement and agreed to maintain absolute discretion about the situation.

McCormick was disturbed by Clement’s explanation, but the extra money was too tempting to refuse. He noted, however, that the pregnant women seemed exceptionally stressed and traumatized, showing signs of severe depression that went beyond what would be expected, even in unplanned pregnancies. Sheriff Mullins occasionally patrolled the area around the plantation, but Clement carefully avoided any suspicious activity during these visits.

He had instructed everyone on the plantation to maintain normal appearances and not reveal anything about the breeding scheme to external visitors. As the pregnancies advanced, Clement began making preparations for the births. He acquired additional medical supplies and studied manuals on childbirth.

Determined to conduct births without external medical assistance whenever possible. This would reduce the risk of exposing his scheme and eliminate potential witnesses. Clement also began establishing contacts with potential buyers for the babies. He made several trips to New Orleans, presenting himself as a slave breeder, specializing in highquality products.

His contacts in the slave market were impressed with his descriptions of the future babies, especially those that would be of mixed ancestry. The first child was born in June 1861. Arlene’s son. The birth was difficult and traumatic, conducted by Clement with minimal assistance from Laya. Arlene suffered complications that nearly resulted in her death.

But Clement was more concerned with the baby’s health than the mothers. Immediately after birth, Clement separated the baby from Arlene, taking him to the slave quarters, where he would be raised by a slave who had recently lost her own child. Arlene was informed she would never see the child again and that any attempt at contact would result in severe punishment. The falsified documents for the baby arrived from New Orleans a week after birth.

The birth certificate listed Laya as the mother, ensuring the child could be legally sold as a slave. Clement was satisfied with the quality of the forgery, which he believed would withstand scrutiny from potential buyers. 3 weeks after birth, Clement sold the baby to a slave trader in New Orleans for $250.

The transaction was conducted through intermediaries, ensuring no connection could be traced back to Delaney Plantation. Clement used the money to pay some of his most urgent debts. Seeing this as validation of his plan, the success of the first sale encouraged Clement to accelerate the timeline for the next pregnancies.

However, he decided to wait at least 6 months before forcing Arlene to participate in new breeding sessions, recognizing she needed time to physically recover from the traumatic birth. The second baby was born in August 1861, Caroline’s son. The birth was even more traumatic than the first, with Caroline suffering severe hemorrhaging that left her unconscious for 2 days.

Clement, concerned only with the baby’s survival, showed irritation with his daughter’s medical complications, seeing them as unnecessary obstacles to his operation. Caroline never fully recovered from the physical and emotional trauma of childbirth. She developed a condition we would recognize today as severe postpartum depression, but which Clement simply saw as feminine weakness. Uni.

When she refused to eat or care for herself, he forced her to consume a mixture of herbs he claimed would restore her strength, but which actually contained substances intended to regulate her reproductive cycle. Caroline’s baby was sold in September 1861 for $275, a slightly higher price due to his particularly European appearance.

Clement was satisfied with the growing profit and began making plans to expand his operation even further, considering the possibility of acquiring additional female slaves specifically for breeding. Freda gave birth in October 1861, but her delivery was complicated by her young age and fragile constitution. The child was born premature and weak, requiring special care that Clement saw as an investment in its future market value.

Freda suffered permanent physical damage during childbirth, including internal injuries that would affect her ability to have children in the future. Dr. McCormick, called to assist with the birth due to complications, expressed concern about Freda’s health, but was silenced by another generous payment from Clement.

The separation from her baby was particularly devastating for Freda. Unlike her older sisters, who had been gradually broken by the process, Freda maintained a spark of resistance that made losing her child even more traumatic. She begged her father to allow her to keep the child, offering to work as a slave in exchange for staying with her baby.

Clement rejected Freda’s pleas with coldness, informing her that maternal feelings were luxuries the family couldn’t afford. He sold Freda’s baby in November 1861 for $225, a lower price due to the child’s fragile health, but still a substantial profit in his distorted perspective. Laya also gave birth during this period, producing a baby that Clement sold without ceremony.

As a slave, Laya had no legal rights over her child, but this didn’t diminish her emotional suffering. Clement forced her to continue working in the big house just days after giving birth, showing total disregard for her physical recovery. Joanna, witnessing the horror unfolding in her own home, began developing signs of mental collapse.

She had repeatedly tried to intervene on behalf of her daughters, but Clement’s threats of physical violence kept her in line. She began drinking secretly, using alcohol to numb the pain of seeing her daughters systematically destroyed. During nights, she was often found wandering the house like a ghost, whispering desperate prayers and asking God’s forgiveness for her inability to protect her daughters.

The mental health of all women on the plantation deteriorated rapidly under Clement’s brutal regime. Arlene developed a catatonic condition, often remaining motionless for hours, staring into nothingness. Caroline had constant nightmares and panic attacks that left her unable to function normally.

Freda, the youngest, showed the most severe signs of psychological trauma. She began having hallucinations, often talking to her absent baby as if he was still present. Clement saw these symptoms as inconveniences that interfered with her reproductive capacity, not as signs of human suffering requiring compassion. In December 1861, after allowing his daughters to recover for several months, Clement forced Arlene to participate in new breeding sessions.

She became pregnant again in January 1862, but her second pregnancy was marked by severe complications that threatened both her life and the babies. Caroline also became pregnant again in March 1862, but her deteriorated physical condition made the pregnancy extremely dangerous. Dr. McCormick, called to examine the women, expressed concern about their ability to survive additional births.

But Clement dismissed these concerns as overly cautious, offering the doctor an additional bonus to keep his opinions to himself. Freda, still recovering from her first traumatic birth, was forced to participate in the breeding scheme again in April 1862. Her second pregnancy was even more difficult than the first.

With complications developing from the early stages, Clement showed irritation with these difficulties, seeing them as obstacles to his operation’s efficiency. The atmosphere at Delaney Plantation became increasingly dark as winter 1862 approached. The women lived in constant terror, never knowing when they would be forced to participate in new breeding sessions or when their babies would be torn from their arms.

Clement in turn became increasingly obsessive and paranoid. He saw conspiracy in any questioning of his actions and responded to challenges with growing violence. His transformation from family man to monster was complete and he seemed incapable of recognizing the humanity of his own daughters. The slaves on the plantation also suffered under Clement’s brutal regime.

Tobias and the other men forced to participate in the breeding scheme showed signs of psychological trauma. knowing they were unwilling accompllices in the destruction of their owner’s daughters. In September 1862, Arlene gave birth to her second child, but the baby was still born due to complications from her difficult pregnancy.

Clement was furious about this investment loss and blamed Arlene for not properly caring for her health during pregnancy. The baby’s death was a devastating blow to Arlene, who had secretly hoped she might be able to keep this child. Carolyn gave birth in October 1862, but suffered severe complications that nearly resulted in her death. Dr.

McCormick worked desperately to save her life, but it became clear she couldn’t survive another pregnancy. Clement, irritated by the reduced productivity, began considering Carolyn a depreciated asset. Freda gave birth in November 1862, but the delivery was so traumatic she nearly died in the process. The baby survived, but Freda was permanently damaged.

Unable to walk without assistance and suffering constant pain, Clement sold the baby immediately, showing total disregard for his youngest daughter’s critical condition. In January 1863, the tragedy that had been building for years finally reached its climax. Freda, unable to endure more suffering and facing the prospect of being forced to become pregnant again despite her deteriorated physical condition, made a desperate decision that would shock even Clement and force Joanna to confront the reality of what her husband had become.

The discovery of Freda’s body on a cold January morning would mark the beginning of the end for Clement Delane’s reign of terror, but would also reveal how far corruption had penetrated the soul of a man who had once been considered a respectable member of southern society. The morning of January 15th, 1863 brought a discovery that would shake the foundations of Delaney Plantation.

Laya found Freda’s body hanging from an improvised rope made of torn sheets in the big house attic. The young woman, only 17 years old, had chosen death as the only escape from the hell her life had become. Clement received news of Freda’s death with a coldness that shocked even Joanna. His first concern wasn’t the loss of his youngest daughter, but the impact her death would have on his reproductive operation.

He quickly calculated that he had lost a valuable productive unit and began considering ways to compensate for this loss. Joanna, on the other hand, was devastated by Freda’s death. The sight of her youngest daughter’s body hanging in the attic broke something fundamental in her psyche.

She realized she had completely failed to protect her daughters and that her pacivity had contributed to the tragedy that unfolded in her own home. That night, she remained kneeling beside Freda’s body for hours, whispering apologies and promises of revenge. Freda’s funeral was a somber and hurried event. Clement insisted on a simple burial in the plantation cemetery, claiming he didn’t want to attract unnecessary attention to the family.

In reality, he feared a public funeral might lead to questions about the circumstances of Freda’s death. Dr. McCormick was called to examine the body and issue a death certificate. He noticed signs of physical trauma on Freda that went beyond what would be expected from suicide, but Clement explained these marks as results of accidents during plantation work.

McCormick was suspicious, but the money Clement had paid him over the years created a silent complicity that prevented him from asking deeper questions. Sheriff Mullins also investigated Freda’s death, but his investigation was superficial. Society of the time rarely questioned deeply deaths that occurred within private properties, especially when involving family matters.

Mullins accepted Clement’s explanation of feminine melancholy as the cause of suicide. Freda’s death marked a turning point for Joanna. She began secretly observing her husband’s activities, mentally documenting the horrors he perpetrated against her surviving daughters. She realized she needed to act, but also knew that confronting Clement directly would be useless and dangerous.

Joanna began establishing discreet contacts with some of the plantation’s most trusted slaves, particularly those who had been forced to participate in Clement’s breeding scheme. She discovered they were also traumatized by their involuntary participation and yearned for a way to resist. Tobias in particular had been deeply affected by his forced participation in the abuse of the Delaney daughters.

He had developed a protective loyalty toward the women and was willing to risk his life to help them. Joanna realized he could be a valuable ally in any plan to stop Clement. During whispered conversations in the slave quarters, Tobias revealed to Joanna that other slaves were also willing to act, united by the shared horror of what they had been forced to witness and participate in.

In February 1863, Arlene was forced to participate in new breeding sessions despite still emotionally recovering from the loss of her second baby. Clement showed total disregard for her grief. Seeing only the need to keep his operation running, Arlene became pregnant again.

But her third pregnancy was marked by even more severe complications. Caroline, physically unable to endure another pregnancy due to damage suffered in previous births, was spared from breeding sessions, but Clement forced her to assume the role of supervisor for other pregnant women. This function traumatized her further, forcing her to be complicit in abuse against her own sister.

Joanna, observing the systematic destruction of her daughters, began formulating a desperate plan. She realized legal authorities offered no protection against the horrors Clement perpetrated and that she would need to take extreme measures to save her surviving daughters. In April 1863, Joanna began secretly meeting with Tobias and other loyal slaves during Clement’s absences.

They discussed in whispers the possibility of direct action against the plantation owner. Tobias revealed there were other slaves willing to participate, men who had been forced to commit acts that violated their conscience and who yearned for a chance at redemption. Clement began noticing subtle changes in the plantation’s atmosphere. In May 1863, the slaves seemed more united, whispering among themselves and interrupting conversations when he approached.

His growing paranoia led him to implement stricter security measures, but this only served to increase tension and resentment. As Arlene’s third pregnancy progressed, it became clear she wouldn’t survive another birth. Dr. McCormick, called to examine her, expressed serious concern about her condition. But Clement dismissed these concerns, focusing only on the potential value of the baby she carried.

In June 1863, Joanna made a decision that would change everything. During one of Clement’s nightly absences for card games, she met with Tobias and three other slaves in the slave quarters. They agreed that the only way to stop the horror was to eliminate Clement permanently. The plan they formulated was simple but effective. Clement had a habit of returning from his gambling sessions late at night, often drunk and vulnerable.

They would wait for him on the trail leading back to the plantation, ambushing him when he was most defenseless. The perfect opportunity arose on a stormy night in July 1863. Clement had made one of his regular trips to a local tavern to play cards, an activity he maintained despite the growing instability of the civil war in the region. Joanna knew he would return late, probably drunk and inattentive.

Joanna and Tobias waited on the trail leading back to the plantation, hidden among the trees lining the path. Two other slaves positioned themselves further ahead on the trail, ensuring Clement couldn’t escape if he tried to flee.

When Clement appeared, staggering on his horse due to alcohol, they ambushed him with efficiency, suggesting careful planning. Clement’s death was quick but not merciful. Tobias knocked him off his horse while Joanna held the animals reigns. They then carefully staged the scene to look like a robbery, scattering Clement’s belongings and wounding the horse to suggest bandits had attacked a lone traveler. The growing lawlessness in the region during the Civil War made such an explanation perfectly plausible.

Clement’s body was discovered the next morning by a neighboring farmer passing through the trail. Sheriff Mullins investigated the scene and concluded Clement had been a victim of bandits, an explanation he accepted without question due to increased violent crime in the area during the conflict.

Joanna perfectly played the role of grieving widow, expressing appropriate shock and sadness at her husband’s death. No one suspected her involvement in the murder, and she was seen as a victim of the tragic circumstances that had befallen her family. During the funeral, she cried genuine tears, not of sadness for Clement’s death, but of relief that her daughters were finally free.

With Clement’s death, the reign of terror at Delaney Plantation came to an end. Joanna immediately freed all slaves and began the process of selling the property, using the resources to care for her traumatized daughters and try to rebuild their lives. Arlene gave birth to her third child in August 1863, but the delivery nearly killed her. With Clement dead, Joanna could finally allow Arleene to keep her baby, a moment of bitter joy after years of horror.

However, the physical and psychological damage Arlene had suffered was irreversible. Carolyn never fully recovered from the traumas she suffered, developing a nervous condition that left her unable to function normally for the rest of her life. She spent entire days in silence, occasionally having episodes where she relived the horrors she had experienced.

Arlene, though physically surviving, carried deep emotional scars that never completely healed. She developed a profound aversion to physical contact and never managed to form normal relationships with men. The baby she was allowed to keep became her only source of joy in a life marked by tragedy. Joanna dedicated the rest of her life to caring for her traumatized daughters. Always carrying guilt for not acting sooner to protect them.

She often wondered if she could have saved Freda if she had found courage to act earlier, a question that would torment her until her death. The truth about what happened at Delaney Plantation died with Clement and was buried with the secrets of those who survived.

Tobias disappeared after liberation, probably moving north where he could live as a free man. Before leaving, he visited Joanna one last time, expressing gratitude that she had found courage to act when official justice failed. Laya also left after liberation, taking with her traumatic memories of her forced participation in Clement’s scheme. She settled in New Orleans, where she worked as a seamstress and never spoke about her years at Delaney Plantation.

Until her death decades later, she carried the physical and emotional scars of her experience. Dr. McCormick continued practicing medicine in the region, but never again accepted questionable payments for his silence. Freda’s death and the subsequent discovery of the horrors at the plantation haunted him for the rest of his career, serving as a constant reminder of the consequences of his silent complicity.

Sheriff Mullins remained ignorant of the truth about Clement’s death until his own death years later. His superficial investigation and easy acceptance of the robbery explanation reflected the limitations and prejudices of a legal system that protected men like Clement while failing to protect their victims.

The story of Delaney Plantation remains as a dark reminder of how desperation and greed can completely corrupt the human soul. Clement Delaney transformed his own family into merchandise, proving that the horrors of slavery could extend far beyond traditional racial lines. What makes this story particularly disturbing are not just the individual acts of cruelty, but the systematic dehumanization that Clement implemented.

He didn’t act on impulse or passion, but with the calculating coldness of a businessman optimizing a commercial operation. His own daughters became productive units in a mental spreadsheet of profits and losses. Southern Society of 1860, with its legal structures that protected absolute patriarchal authority, created the perfect environment for such horrors to flourish in secret.

The laws governing slavery, originally intended to maintain control over enslaved African populations, were perverted by Clement to enslave his own descendants. Doctor McCormick and Sheriff Mullins, representatives of the established social order, completely failed to recognize or intervene in the horrors unfolding right before their eyes.

Their superficial investigations and acceptance of convenient explanations reveal how society of the time was structured to protect men like Clement, not their victims. Joanna’s final resistance represents both redemption and tragedy. Her decision to orchestrate her husband’s death came too late to save Freda and prevent years of trauma for her other daughters.

However, her action demonstrates that even in the most desperate circumstances, human conscience can eventually rebel against absolute evil. Tobias and the other slaves who participated in revenge against Clement show how oppression can create unexpected alliances. United by shared suffering, they transcended racial barriers imposed by society to seek justice when the legal system failed.

The fate of Clement’s surviving daughters illustrates how trauma can leave permanent scars that no amount of subsequent care can completely heal. Arlene and Carolyn carried the physical and psychological marks of their experience for the rest of their lives, living reminders of the horrors they endured. The ease with which Clement managed to falsify documents and sell babies reveals the fundamentally corrupt nature of the slavery system.

A market that treated human beings as property inevitably created opportunities for even more extreme abuses where even the most sacred family bonds could be monetized. Perhaps the most shocking aspect of this story is how Clement managed to rationalize his actions. In his distorted mind, he wasn’t abusing his daughters. He was saving the family through necessary sacrifices.

This capacity for self-justification shows how apparently normal people can become monsters when circumstances and incentives align perversely. Delaney plantation was eventually sold and divided into smaller parcels. The big house was demolished in the 1870s and today nothing remains to mark the place where so many horrors were perpetrated.

The land that once witnessed such cruelty now sustains peaceful crops as if nature itself were trying to erase memories of what happened there. Official records of the time list Clement Delaney simply as killed by bandits and Freda as victim of melancholy. These sanitized descriptions hide the brutal truth of their deaths and perpetuate the invisibility of victims of domestic abuse and sexual exploitation. This story forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth. Monsters are rarely strangers hiding in

shadows. More often, they are fathers, husbands, and authority figures who use their position of trust to perpetrate the worst types of abuse. Social respectability can be a perfect mask for the deepest depravity. Joanna’s final courage, though it came too late to prevent complete tragedy, offers a lesson about the importance of acting against injustice, even when personal cost is high.

Her decision to orchestrate Clement’s death was morally complex. An act of vigilante justice born from the complete failure of the legal system to protect the innocent. Today, when we hear about cases of domestic abuse or sexual exploitation, we must remember that victims often face the same obstacles as the Delaney daughters, authorities who don’t believe them, legal systems that protect perpetrators, and societies that prefer to ignore inconvenient truths.

The story of Delaney Plantation remains as dark testimony to human capacity for both absolute evil and heroic resistance. It reminds us that eternal vigilance is the price of protecting the vulnerable and that sometimes justice can only be achieved through means that society itself considers illegal. On silent nights in the Mississippi Delta, when wind blows through fields where Delaney Plantation once existed, some say you can still hear echoes of the past, not supernatural ghosts, but persistent memories of injustices that were never adequately recognized or repaired. This is a story that forces us to look into the darkest corners of

human nature, but also reminds us that even in the most desperate circumstances, there always exists the possibility of resistance, redemption, and eventually justice. Even if it comes by the hands of those society least expects to deliver it. If this dark investigation has captivated you, make sure to subscribe to Legacy of Fear and hit that notification bell.

We dive deep into the shadows of history to uncover stories that mainstream sources won’t touch. Tales of human depravity, supernatural encounters, and mysteries that continue to haunt us today.

News

CEO Fired the Mechanic Dad — Then Froze When a Navy Helicopter Arrived Calling His Secret Name

Helios Automotive Repair Shop Jack Turner 36 years old single dad oil stained coveralls grease under his fingernails he’s fixing…

I Watched Three Bullies Throw My Paralyzed Daughter’s Crutches on a Roof—They Didn’t Know Her Dad Was a Special Ops Vet Watching From the Parking Lot.

Chapter 1: The Long Way Home The war doesn’t end when you get on the plane. That’s the lie they…

The Teacher Checked Her Nails While My Daughter Screamed for Help—She Didn’t Know Her Father Was The Former President of The “Iron Reapers” MC, And I Was Bringing 300 Brothers To Parent-Teacher Conference.

Chapter 1: The Silence of the Lambs I buried the outlaw life ten years ago. I traded my cuts, the…

They Beat Me Unconscious Behind the Bleachers Because They Thought I Was a Poor Scholarship Kid. They Didn’t Know My Father Was Watching From a Black SUV, and by Tomorrow Morning, Their Parents Would Be Begging for Mercy on Their Knees.

Chapter 3: The War Room I woke up to the sound of hushed voices and the rhythmic beep of a…

I Was Still a Virgin at 32… Until the Widow Spent 3 Nights in My Bed (1886)

“Ever think what it’s like? 32 years on this earth and never once laid hands on a woman—not proper anyhow….

What They Did to Marie Antoinette Before the Guillotine Was Far More Horrifying Than You Think

You’re about to witness one of history’s most calculated acts of psychological warfare. For 76 days, they didn’t just imprison…

End of content

No more pages to load