He was a tapestry of contradictions. A poet who could write “Dear Mama,” a tender ode that became an anthem for struggling mothers everywhere, and in the next breath, unleash “Hit ‘Em Up,” a track of such raw, untamed vitriol that it’s still debated in hushed tones today. He was a revolutionary with the magnetic pull of a cult leader and a paranoid star who saw enemies in the shadows of his own entourage.

For decades, the world has debated the legacy of Tupac Shakur. We know the music, the films, and the tragic, unsolved end. But a different, more complex question has always lingered, whispered by those who knew him and those who studied him: What made Tupac so dangerous?

It’s a question that his peers, collaborators, and even his rivals are still trying to answer, and their insights paint a chilling portrait of a man who was a threat on multiple fronts: a political danger to the establishment, an artistic danger to the status quo, and, perhaps most tragically, a profound danger to himself.

The “Malcolm X” of Hip-Hop

When you ask Wu-Tang Clan’s mastermind, RZA, what made Tupac dangerous, his answer has nothing to do with street credentials. He points to something far more potent: Tupac’s mind.

“He was probably more dangerous than Notorious B.I.G.,” RZA explained, clarifying that it wasn’t about who was “tougher.” Biggie, he said, “communicated love, but he wasn’t starting revolutions.”

Tupac was different.

“Pac had the power to infuse your emotional thought,” RZA noted, referencing the spectrum of his work. He could tap into empathy with “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” then, with the flip of a switch, “arouse the rebel in you.” This, in RZA’s eyes, was the ultimate threat. He was a man who could not only make you feel, but make you act.

RZA’s comparison was heavy and deliberate: “He was more going into the Malcolm X of things.” Society, he argued, fears that combination. A person who can articulate love, pain, and revolution is a person who can dismantle systems. That was the danger that made the establishment nervous, the kind of danger that lands you on FBI watchlists. He wasn’t just a rapper; he was a potential leader of a movement.

This sentiment was echoed by one of the greatest lyricists to ever touch a microphone: Eminem. In a heartfelt 2015 letter, Eminem described Tupac’s artistry as its own form of danger. It wasn’t just technical skill; it was the “unmatched ability to make you feel everything he was going through.”

“A lot of people say ‘you feel Pac,’ and it’s absolutely true,” Eminem wrote. “His spirit spoke to me… you just felt every aspect of his pain, every emotion.” This raw, emotional transference breaks down the wall between artist and audience. When millions of people feel your rage as their own, that is a power that money can’t buy and a government can’t easily control. It was, as Eminem put it, “urgent.”

Loyalty, Paranoia, and the Devil on His Shoulder

But this revolutionary fire had a dark side. The man who could inspire millions was also, according to those closest to him, an impulsive and volatile man grappling with very real threats.

Napoleon, a founding member of Tupac’s group, The Outlawz, saw this side up close. He described a man of terrifying loyalty, a man who would “put his career on the line, his life on the line.” He recounted the infamous, and true, story of Tupac witnessing two off-duty police officers beating a Black man. Tupac didn’t just intervene; he “jumped out, shot both of them.” They turned out to be undercover cops. This was the “all out” nature of Tupac’s loyalty.

But after being shot in New York and serving time in prison, that loyalty curdled with something darker. Napoleon explained that when Tupac came to Death Row Records, he was more aggressive, but it wasn’t without reason. “You got to understand that he had actually people that wanted to murder him,” Napoleon stated. “The people that came to shoot him in that… studio, they came with the intention to murder him. And the word on the street is that these same people still wanted to murder him.”

This paranoia, whether justified or not, began to consume him. The Death Row studio, Napoleon recalled, felt like “the streets.” You had to “always be on point.”

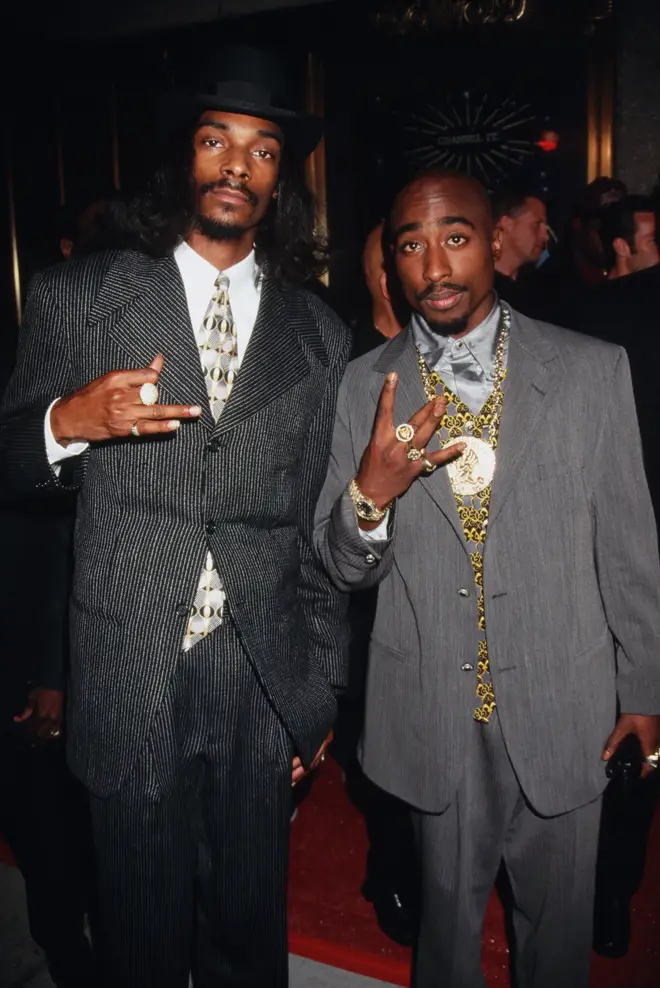

This tension bled into his closest friendships, creating the most tragic fractures of his final days. His relationship with Snoop Dogg, once his brother-in-arms at Death Row, disintegrated. Snoop described a tense plane ride just days before Tupac’s death. Pac was furious because Snoop had said in an interview that he had no beef with Biggie and Puff Daddy—a peacemaking gesture in an escalating war.

“He was mad at me… he was furious,” Snoop recalled. The weight of that final interaction haunts him. “Two days before he died,” Snoop said, his voice heavy with regret, “I don’t think he liked me.”

Snoop saw this self-destructive streak clearly. He “didn’t like” the diss track “Hit ‘Em Up.” He called it “buying problems.” Tupac, in his rage, was no longer just beefing with rappers; he was provoking “real gangsters,” the very people who, Snoop believes, ended up taking his life.

When Beef Turns Real

Snoop wasn’t exaggerating. The beef Tupac instigated wasn’t just lyrical. Mobb Deep’s Prodigy, a target of “Hit ‘Em Up,” was chillingly candid about his intentions.

“Oh yeah, I wanted to kill that [Tupac],” Prodigy admitted in a 2012 interview. “Hell yeah. I want to… jump him, cut him, shoot him, all that shit. ‘Cuz it was beef.”

This was the consequence of Tupac’s volatility. He had turned a war of words into a real-world, life-or-death hunt. “It was a dangerous time for us,” Prodigy explained, describing touring in California as being “on the front lines” in enemy territory. Havoc, the other half of Mobb Deep, confirmed their intentions, stating that if Tupac hadn’t died, the beef “would have went further, lyrically and probably physically.”

Tupac’s paranoia became a feedback loop. He was “hyper sensitive,” as rapper Xzibit was told by the Outlawz. Xzibit found himself an accidental target. His song “Paparazzi” contained a line about rappers being “only for the money and the fame.” It was a purist, underground statement, but because Tupac had a song with a similar line, word got back to him that Xzibit was dissing him.

Rapper Ras Kass tells an even more terrifying story. He was featured on a Chino XL track where Chino infamously dissed Tupac with a line about prison. Ras didn’t write the line, didn’t approve of it, and “was not happy about it.” When “Hit ‘Em Up” dropped, he panicked, thinking, “I’m next.” His fear peaked when Tupac called his label and demanded 50 tickets to his release party. “Ah, he’s going to get me,” Ras thought, convinced Pac was bringing a crew to attack him.

The twist? It was all a misunderstanding. Tupac actually respected Ras Kass and had even included him on a “perfect album” concept he’d written in prison. But the fear was real. The atmosphere Tupac had created was so toxic and so violent that even a sign of respect was interpreted as a death threat.

This all culminated in the final, fatal act. As controversial manager Wack 100 bluntly put it, the MGM Grand fight wasn’t “dangerous;” it was “stupid.” “You don’t initiate a stomping out of a known killer… and think ain’t nothing gonna happen.” From Wack’s perspective, this was the ultimate, tragic expression of Tupac’s “studio gangster” persona—an impulsive, performative act of “thug” loyalty that got him killed.

This was the paradox of Tupac Shakur. He was a genius with the soul of a poet and the strategic mind of a revolutionary. But he was also a young, traumatized man, wounded by betrayal and imprisonment, who wrapped himself in an armor of aggression. He was dangerous to the system, as RZA said. He was artistically dangerous, as Eminem said. But in the end, the paranoia, the impulsiveness, and the impossible weight of the “Thug Life” crown he wore made him the most dangerous of all to the one person he couldn’t escape: himself.

News

“You Paid For Me… Now Finish It.” She Said – But What He Found Underneath… Shattered Him.

They don’t write songs about the kind of evil that hides behind money and power. Not out here. Not under…

Quiet Rancher Saw His Maid Limping, What He Did Next Shook the Sheriff’s Office

He looked like any other quiet rancher. Weathered hands, worn boots, a man who spoke only when necessary. But when…

Poor Rancher Married Fat Stranger for a Cow — On Wedding Night, She Locked the Door

Ezekiel Marsh stood at the altar next to the heaviest woman he’d ever seen, knowing he’d just traded his dignity…

I Saved an Apache Widow from a Bear Trap — Next Morning Her People DEMANDED I TAKE HER

I couldn’t tell you what day it was might have been a Tuesday might have been the ass end of…

They Knocked the New Girl Out Cold — Then the Navy SEAL Woke Up and Ended the Fight in Seconds

The sun was barely rising above camp horizon when the new trainees gathered near the obstacle yard. The air smelled…

I Returned From War To Find A Teacher Scrolling Facebook While A Bully Dragged My Daughter By Her Hair—He Thought I Was Just A Helpless Parent, Until He Saw The Uniform.

Chapter 1: The Long Way Home The silence in the cab of my truck was deafening. It wasn’t the heavy,…

End of content

No more pages to load