In the red clay farmlands of Cumberland County, North Carolina, the world once seemed simple. It was a place where families survived on tobacco and cotton, where Sunday services filled the Baptist church, and where neighbors trusted each other so completely that a handshake was as binding as a contract.

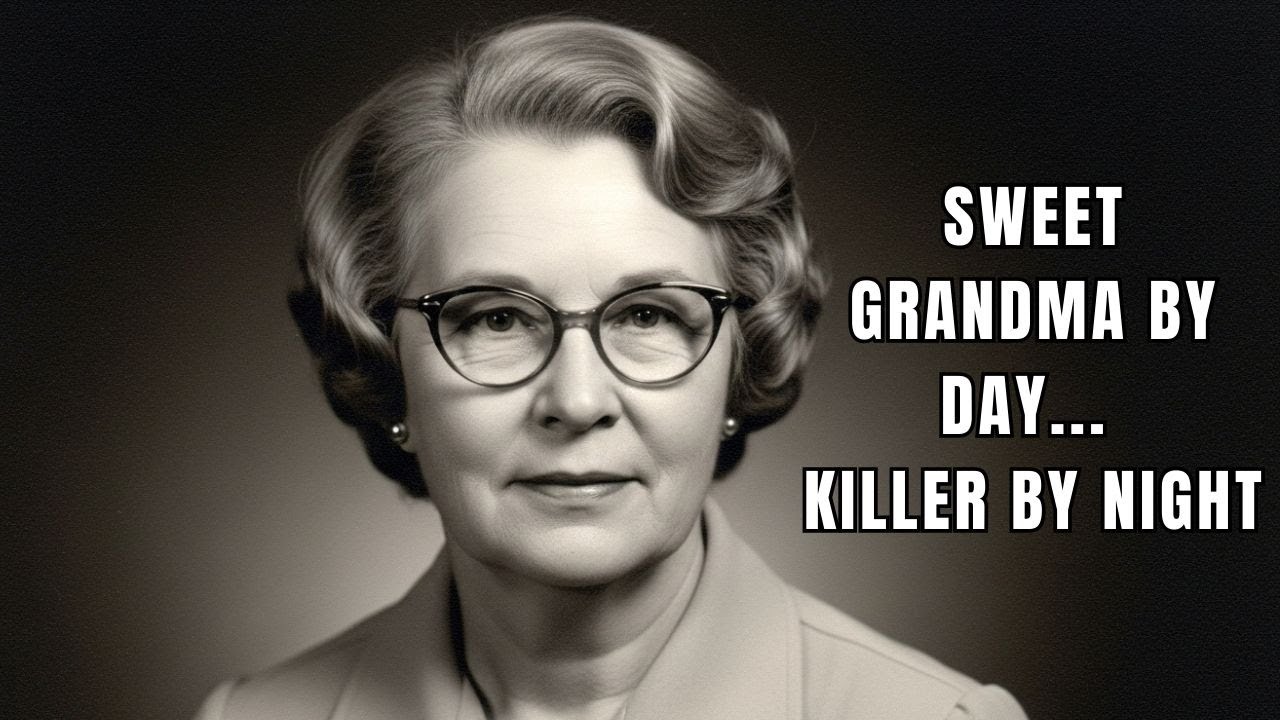

Into this world, on October 29th, 1932, a little girl named Margie Velma Bullard was born. She would grow into a soft-spoken, church-going woman and eventually one of America’s most notorious killers. Velma’s childhood was framed by poverty, but not despair. Her family farm lacked electricity and running water, yet hardship was considered normal in rural Carolina.

Faith was the true foundation. The Bullard home was governed by strict Pentecostal rules. prayers before meals, scripture before bed, and an unshakable belief that God watched every action. Outwardly, Velma absorbed these lessons. Obedient, polite, and by all accounts, a bright, promising child. Teachers remembered her as helpful and clever, excelling at reading and writing, and even surprising classmates with her talent on the basketball court.

But discipline at home was harsh. Her father’s strictness was unyielding. And when Velma’s mother gave birth to twins, responsibility shifted heavily onto Velma. She was forced to abandon basketball, her one taste of freedom and instead tend to housework and child care. The bright girl who once dreamed of independence was tethered to duty.

In her teenage years, Velma met Thomas Burke, a lanky boy with gentle humor. Their courtship was cautious. Her father forbade dating until 16, but the attraction was undeniable. At 17, desperate for escape from her suffocating home life, Velma eloped with Thomas. They settled into a modest house full of hope that marriage would give them the stability and love they both craved. For a time, it did.

Velma was a beautiful wife, Thomas a hard-working mill employee, and together they dreamed of raising a family far from the hardship they had known as children. Yet, Destiny had other plans. A devastating car accident left Thomas with severe injuries and crippling headaches. Unable to work, he turned to alcohol.

The very Svelma’s religious upbringing condemned above all else. This was the first fracture in Velma’s carefully built world. A marriage poisoned not by arsenic but by despair. As Thomas drowned himself in bottles, Velma turned to prescription drugs to soothe her own anxiety. Neither knew it then, but in those bottles and pills lay the beginnings of a path that would twist from desperation into something far darker.

By the mid 1960s, the Burke household had transformed from a hopeful beginning into a battlefield. Thomas, racked by pain and bitterness, drank heavily. Velma, humiliated by his decline and desperate to cope, relied on tranquilizers prescribed by local doctors. Their home, once built on fragile dreams of love, was now ruled by silence, arguments, and suspicion.

In April 1969, everything came to a violent end. One evening, Velma took her two children out on a strange errand. Hours later, when they returned, the Burke home was engulfed in flames. Neighbors rushed to the scene, horrified as Thomas’s body was found inside. The official ruling was accidental.

A cigarette left smoldering while he slept. A tragic but common cause of rural fires. Velma’s grief was convincing. She wailed and tried to throw herself into the burning house. She played the part of a devastated widow perfectly, and the community believed her. Yet a few neighbors whispered about odd details. valuables removed days before, the convenient timing of her absence with the children, and later an insurance payout that left Velma more financially secure than ever.

If this was a performance, it was flawless. The widow received sympathy, money, and a fresh start. But Thomas Burke’s death was not the end. It was the beginning. 16 months later, Velma remarried. This time to Jennings Barfield, a respected widowerower with land, income, and a good reputation. To the outside world, Velma seemed fortunate.

To Jennings, she appeared the perfect wife, devout, attentive, an excellent cook, and devoted to his household. But beneath the domestic surface, Velma’s drug dependency deepened. Her need for pills demanded money, and money demanded deception. Soon, Jennings discovered forge checks and suspicious withdrawals from his accounts.

Their confrontation was explosive. Jennings, unlike Thomas, was strong willed and unwilling to tolerate betrayal. Divorce loomed. Exposure seemed inevitable. But before Jennings could act, he collapsed with sudden stomach cramps, nausea, and violent vomiting. Velma was right by his side, feeding him broth, calling doctors holding his hand.

She played the devoted wife to perfection, while the rat poison she had slipped into his meals completed its work. Within hours, Jennings was dead. The doctors called it heart failure. The community called it tragic.Velma wept, prayed, and collected her second husband’s life insurance. Fire had given her the first taste of freedom.

Poison gave her something more, a method, quiet and invisible, that could mask murder as mercy, and Velma Barfield had just discovered how easy it was to kill. After Jennings’s death, Velma returned to Fagatville, closer to her aging parents. To neighbors and fellow churchgoers, it looked like a daughter stepping back into her family’s embrace.

But behind the mask of filial devotion, Velma had found her next opportunity. Her father was dying of lung cancer, a death that would come naturally. But her mother, Lillian Bullard, was different. At 74, she still lived independently, managing her modest pension and savings with meticulous care. She was cautious, frugal, and quietly proud of the nest egg she had built.

To Velma, deep in debt from drugs and dependent on fraud to survive. Her mother’s finances were both temptation and threat. Velma began small, forging checks, borrowing in Lillian’s name, skimming from accounts she promised to help manage. At first, the sums were minor, small enough to pass unnoticed.

But addiction is hungry, and Velma’s thefts grew larger, bolder. By 1974, she was stealing hundreds each month. Discovery was inevitable, unless, of course, the one person who could expose her was removed. That summer, Lillian began to fall ill. Mysterious stomach cramps, sudden vomiting, weeks of unexplained weakness.

Each episode came and went, puzzling doctors, but always witnessed by her ever faithful daughter. Velma was there with broth, with medicine, with whispered reassurances. She was the devoted caregiver and the silent executioner, experimenting with arsenic doses that mimicked natural sickness. The community saw only devotion.

Neighbors praised Velma’s sacrifice, her daily visits, her gentle nursing care. Lillian herself grew more dependent, more grateful, blind to the fact that the hands she trusted most were slowly killing her. On December 28th, 1974, the final act began. Lillian’s pain was unbearable. Her vomiting relentless. Velma stayed by her side through the ambulance ride, through the hospital stay, through every worsening hour.

Doctors could find no cause. By December 30th, Lillian was dead. The records listed acute gastroenterteritis. Another tragedy, another inexplicable illness. Velma wept as only a daughter could. The funeral was filled with sympathy. No one questioned the woman who had just lost her mother. But for Velma, grief was only another mask.

Her thefts were buried with her mother, legitimized by inheritance, erased by death. And more importantly, she had crossed the unthinkable line. If she could murder her own mother and escape suspicion, then no one, family, friend, or stranger, would ever truly be safe. By 1976, Velma Barfield had perfected her mask.

To the outside world, she was a grieving widow and a beautiful daughter, now turning her Christian devotion toward helping others. She found work as a home health aid, the perfect cover for a woman who had learned to kill quietly. Her first patients were Montgomery and Dolly Edwards, an elderly couple in their 90s and 80s.

They welcomed Velma as if she were family, grateful for her cooking, cleaning, and prayers. To them, she was a blessing. To Velma, they were targets. Within weeks, she was forging Montgomery’s checks, draining their accounts with careful precision. Montgomery’s death in early 1977 raised no suspicion. At 94, the end seemed natural expected.

Velma played her role flawlessly, comforting Dolly, staying by her side in widowhood. But when Dolly began asking questions about missing money, her fate was sealed. By March, she too was struck by sudden violent illness. Velma spoonfed her teas and soups, all laced with poison. Dolly’s death was mourned as a tragedy, while Velma was praised for her tender care.

Her reputation as a devoted caregiver only grew. The Edwards family spoke highly of her, passing her name to friends in need. That trust led her to John Henry and Record Lee, another elderly couple. Velma integrated herself into their lives with practiced ease, managing medicines, finances, and meals. Once again, she began siphoning money.

And once again, when John Henry noticed irregularities, his health suddenly declined. The symptoms were familiar now. Cramping, vomiting, unbearable pain. Within two days he was dead. Doctors blamed age and illness. Velma wept on Q. The Lees like the Edwards before them never suspected the woman who prayed over their meals, who quoted scripture as she wiped their brows.

Velma had built a perfect disguise. A grandmotherly caregiver whose piety made suspicion unthinkable. What made these murders even more chilling was their intimacy. Poisoning is not distant. It requires presence. Preparing food, offering drinks, holding a hand as the victim writhes in agony.

Velma delivered death in the same gestures that appeared to offer love. By late 1977,Velma had mastered her craft. In Cumberland County, tragedy seemed to follow her, but no one dared connect the dots. Death was her currency. sympathy, her shield, and behind her gentle smile, the mask of the caregiver hid a predator no one wanted to imagine.

By the winter of 1977, Velma Barfield’s trail of silent deaths stretched across families and towns. Yet suspicion had never caught her. Her faith, her grandmotherly demeanor, her whispered prayers, all had shielded her. But when she met Stuart Taylor, the shield began to fracture. Stuart was different from her previous victims.

At 56, he was not frail, not elderly, not someone whose sudden decline could be easily explained. He was a tobacco farmer, plain spoken and steady, still healthy enough to manage his land. Widowed and lonely, he found comfort in Velma’s domestic care. She cooked, cleaned, and filled the quiet of his farmhouse with the rhythms of prayer and companionship.

To the outside world, it was a wholesome match. To Velma, it was security and another account to access, but Stuart was sharper than her elderly charges. By early 1978, his banker noticed irregularities, checks forged, amounts missing. Stuart confronted Velma, furious at the betrayal. For the first time, someone close to her saw through the mask.

And for Velma, discovery meant danger. She had learned one lesson well. Dead men tell no tales. On the evening of January 31st, 1978, Stuart and Velma attended a Pentecostal revival meeting. Surrounded by hundreds of worshippers, Stuart suddenly grew pale. Sharp stomach cramps struck. Nausea overwhelmed him, and he staggered from his seat.

Congregants remembered Velma by his side, touching his shoulder, whispering comfort, guiding him out with a look of pure devotion. None could have imagined the poison already courarssing through his veins. At home, Stuart’s condition worsened. For three days he writhed in agony, vomiting until he could not stand, gasping from the pain tearing through his chest. Velma never left his side.

She brought him teas, broths, and medicine, all dosed with arsenic. To neighbors, she appeared the model of loyalty, nursing her companion through a mysterious illness. But Stuart’s family saw something others had missed. He had been healthy, strong, and in conflict with Velma over missing money. His sudden death did not fit the narrative of natural decline.

This time, they demanded an autopsy. The results were undeniable. Stuart Taylor’s body was saturated with arsenic. For nearly a decade, Velma’s mask had hidden her crimes. But with Stuart’s death, the truth began to bleed through. The grandmotherly caregiver was about to be unmasked as a serial killer. Stuart Taylor’s autopsy shattered the illusion Velma had crafted for nearly a decade. Arsenic, lethal, unmistakable.

Investigators began retracing her past, exuming bodies connecting threads long dismissed as coincidence. One by one, the tragedies surrounding her were recast as deliberate murders. husbands, patients, even her own mother. All victims of the woman Cumberland County had trusted most. Velma was arrested in March 1978.

Under questioning, her composure cracked. Detectives listened in disbelief as she described her methods with chilling detachment. The powders measured, the doses timed, the symptoms monitored. She claimed she never meant to kill, only to sicken her victims long enough to replace the money she had stolen.

But the pattern was too precise, too rehearsed. Death had been her solution time and again. Her trial in November drew national attention. The spectacle was unprecedented. a grandmother, small-framed and soft-spoken, accused of being a calculating serial killer. The prosecution laid out a trail of forgery, theft, and murder anchored by the undeniable proof of Stuart Taylor’s poisoning.

The defense leaned on drug addiction, mental illness, even dissociative personalities. None could outweigh the evidence. The jury deliberated less than an hour before declaring Velma guilty of first-degree murder. She was sentenced to death. The first woman in North Carolina to face execution in decades. Appeals dragged on for 6 years, but the verdict never changed.

On death row, Velma underwent a dramatic transformation. She embraced religion, leading Bible studies, counseling inmates, and corresponding with evangelicals. Supporters, including Billy Graham, petitioned for clemency. They called her reformed, a grandmother redeemed. But the families of her victims saw only manipulation.

The same mask she had worn in kitchens and sick rooms, now repurposed in a cell. Governor Jim Hunt refused clemency. The weight of six lives and the countless more suspected was too heavy. On November 2nd, 1984 at Central Prison in Raleigh, Velma Barfield was executed by lethal injection. She was the first woman in US history to die by that method.

Her last words were brief, apologetic. Her last meal, cheese doodles and Coca-Cola, childlike in its simplicity. Velma’sstory endures not just as true crime, but as warning. She revealed how evil can wear the mask of kindness. How communities built on faith and trust can be blindsided by betrayal. In her wake came changes, closer scrutiny of unexplained deaths.

More caution with caregivers. Yet one question lingers still. How many others, uncounted and unexamined, lay buried in her shadow?

News

German Colonel Vanished in 1945 — 78 Years Later, His Secret Alpine Cabin Was Found

Berlin. April 1,945. The heart of the Third Reich is crumbling under the weight of a thousand Allied bombs. Soviet…

1808-1865: How the United States Bred Slaves Like Breeding Animals and Sold Them

1808-1865: How the United States Bred Slaves Like Breeding Animals At 1808, the United States Congress took a decision that…

The Colonel Who Shared His Wife with 7 Slaves: The Deal That Destroyed a Dynasty

There are nights that carry silence too heavy not to hide a secret. This story begins with a night like…

The Prescott brothers – posthumous photograph of them buried alive (1858)

The Prescott Brothers (1858) In the small town of Fairhaven, State Massachusetts, in 1858 photography was a rarity. People didn’t…

This 1903 wedding portrait looks ordinary—until you zoom in on the bride’s hand…

The Mystery of the 1903 Wedding Portrait The spring of 1903 brought to English Yorkshire is a rare revival. In…

(1873, Emma Richter) The Girl Science Couldn’t Explain

Milwaukeee’s German Quarter, 1873, lay tucked against the steel gray expanse of Lake Michigan. Its narrow streets smelled of yeast…

End of content

No more pages to load