What they did to Anne Boleyn before her execution was so horrific that they wanted to erase it from the historical record.

The sword’s blow was swift, but death was not. For up to 30 seconds of pure terror, Anne Boleyn’s eyes still blinked. Her consciousness, trapped inside her severed head, remained horrifyingly intact. She saw the pale London sky one last time. She heard the wet, intimate sound of her own blood soaking into wood, cloth, and straw. But this physiological nightmare, this final twitching awareness, was nothing compared to what had already been done to her.

The story you’ve been told about Anne Boleyn’s dignified execution is a carefully maintained lie. What they did to her was not justice; it was a spectacle of humiliation so deliberate, so methodically designed, that decapitation became a release rather than a punishment. The blade was mercy. If you’re drawn to real history, where innocence is destroyed in silence, subscribe. This isn’t a myth; it’s the slow breaking of a young woman the world chose to hate. Before the screams, before the blade, Anne Boleyn was just a girl, frightened, isolated, and already condemned. Comment where you’re watching from and stay with me, because what you’re about to hear is not a romantic tragedy—it is something far darker.

Anne Boleyn’s execution stands as one of the clearest examples of Tudor justice at its most sadistic, where death was merely the final punctuation in a long campaign of psychological destruction. Most history books reduce her fate to a single line: beheaded for treason. But the reality of her final days reveals a dismantling so meticulous it would be recognizable to modern interrogators. Her execution was not simply an ending; it was the final act in Henry VIII’s campaign to obliterate a woman who had become inconveniently powerful, and the worst part is, this targeting began long before the scaffold was built.

By May 19, 1536, Anne Boleyn had already endured 17 days of imprisonment inside the Tower of London—the same fortress where she had once prepared for her coronation just 3 years earlier. She had walked these grounds in anticipation of becoming Queen of England, crowned in spectacular ceremony at Westminster Abbey. Now, she awaited death inside the same walls, suspended in a cruel, repeatedly delayed limbo. Her execution date was announced, then withdrawn, then announced again. This was not administrative confusion; it was calculated torment. By stretching time, Henry VIII ensured Anne would be forced to live inside her own execution, rehearsing it endlessly in her mind. Each dawn brought the same question: Is this the day they kill me? Each night ended without an answer.

And still, this was not the worst thing being done to her. The King had even summoned a skilled swordsman from Calais, rejecting the traditional English axe. This detail is often framed as compassion, but mercy has nothing to do with it. The imported sword transformed the execution into theater—a performance engineered for precision, spectacle, and psychological dominance. Anne was meant to understand that even her death would no longer belong to England; it belonged solely to the King.

During her final hours, witnesses described Anne as possessing an almost supernatural calm. Some even called her cheerful; she laughed, she joked. Modern psychology recognizes this response immediately: dissociation—a defense mechanism triggered by extreme trauma. When the mind no longer believes survival is possible, it detaches. Anne reportedly joked that she would be known as “Headless Anne”—a macabre humor masking emotional collapse. What appears to be courage is often the mind’s last shield.

Few historical accounts pause to acknowledge the sheer terror she must have endured, not just fear of death, but fear of annihilation. She knew her reputation was being systematically dismantled through fabricated accusations: adultery, incest, conspiracy to murder the King—charges so implausible they would be dismissed instantly today. That was precisely the point. This was not about truth; this was about replacement. Henry VIII did not merely want Anne dead; he wanted her history erased, her contributions nullified, and her daughter Elizabeth delegitimized. The execution was not the punishment; it was the justification, and the reputation assassination was still unfolding.

In the days before her death, Anne was forced to listen as grotesque, invented tales of her supposed sexual depravity circulated freely beyond her walls. These stories were repeated so relentlessly that they began to feel real to those who heard them—accusations so bizarre that no legitimate court would entertain them, yet they were enough when power demanded belief.

The morning of May 19th dawned unusually clear over London, a cruel contrast to what was about to occur. Anne had spent the night in prayer; sleep escaped her repeatedly. Tower records show that at 2:00 a.m. she requested the sacrament and remained kneeling for hours, clinging to ritual as her only remaining certainty. By dawn, she had been awake for nearly 24 hours. Her body was exhausted, her mind was fractured. When the Tower Lieutenant arrived to escort her, Anne was reportedly laughing with her ladies-in-waiting. This was not peace; it was collapse.

Anne’s execution had been scheduled, postponed, rescheduled, and delayed again—an often overlooked but devastating form of torture. The uncertainty, not knowing exactly when death would arrive, was deliberate. Only when the hour had finally come was Anne informed. She was led from her chambers, through corridors where she had once walked as Queen, to be. Courtiers, bowing as she passed, now guards flanked her—not to honor her, but to prevent her from running. The same courtiers who once depended on her favor watched in silence; indifference had replaced loyalty.

The scaffold erected on Tower Green was abnormally low, barely 90 cm. Unlike the elevated platforms often shown in films, this design forced Anne to climb only a few shallow steps. This was not convenience; it denied her elevation, denied her symbolic dignity. It kept her face level with the crowd. Although modern depictions often portray solemn silence, contemporary records suggest something very different: a carnival-like atmosphere had been encouraged. This was public theater, a warning to anyone, especially women, who might dare to overstep the boundaries of power.

Before kneeling, Anne was permitted a final speech, not out of mercy but because tradition required it. Her words were precise and controlled: “Good Christian people, I am come hither to die according to law.” This apparent submission was her final act of defiance. By acknowledging the law without admitting guilt, she subtly exposed the illegitimacy of the accusations. She would die obedient, but unconfessed.

Perhaps most disturbing of all was the King’s absence. Unlike other royal executions, Henry VIII did not attend. Instead, he waited at Whitehall Palace for confirmation of Anne’s death, even as preparations were made for his marriage to Jane Seymour. Anne’s death had become logistical; the personal was now entirely political.

The swordsman from Calais, specifically selected and lavishly paid, represented another layer of calculated cruelty. English executions relied on an axe—messy, imprecise, often requiring multiple blows. The foreign swordsman promised efficiency. In her final moments, Anne would die not at the hands of her countrymen, but at the hands of a stranger—one last displacement. Her blindfold, often portrayed as mercy, served a practical purpose: preventing her from flinching.

Anne knelt upright rather than placing her head on a block—a French custom that intensified the executioner’s challenge. She had to remain perfectly still through sheer will. Witnesses reported her lips moving constantly in prayer, eyes darting beneath the blindfold, straining to detect movement, breath, sound. Death was coming; she just didn’t know when. That suspended instant, the waiting, was its own form of torture. The decapitation itself, by Tudor standards, was flawless—a single, clean blow.

And that was only the beginning. A single expertly delivered blow severed Anne’s head, but what followed is rarely included in polite historical retellings. According to multiple eyewitness accounts, Anne Boleyn’s eyes and lips continued to move for several seconds after the decapitation. Not metaphorically—physically. This horrifying response occurs when residual oxygen remains in the brain tissue, allowing brief involuntary movement even after the body has been destroyed. Some witnesses claimed her lips appeared to form words, perhaps the final syllables of the prayer that had been interrupted by the sword. For those watching, the effect was deeply unsettling. Several fainted; others turned away in visible distress. This moment, when the boundary between life and death blurred, shattered any illusion that the execution was clean, merciful, or humane. It exposed the fragile, unfinished nature of dying in a way that few present would ever forget.

And yet the cruelty did not end there. Perhaps most revealing of all was what had not been prepared: there was no proper coffin waiting for Anne’s remains. Her ladies-in-waiting, still shaking, still grieving, were forced to scramble in confusion to find something—anything—to hold what remained of their Queen. They eventually located a wooden chest used for storing arrows. Into this crude container, Anne Boleyn’s severed head and body were placed together. This was not a trivial oversight; it was a statement. Even in death, Anne was treated not as a human being worthy of dignity, but as a resolved political inconvenience—a problem already crossed off a list. She was hastily buried beneath the floor of the Tower Chapel without proper Christian ceremony, as though those responsible expected her memory to disappear as quickly as her life had ended.

But erasure requires effort, and Henry VIII was committed. The campaign to destroy Anne Boleyn did not stop at her execution. Court painters were instructed to destroy her portraits. Royal insignia bearing her symbols were ripped down from walls and tapestries. Courtiers quickly learned that speaking Anne’s name, let alone defending her, was now dangerous. Silence became survival. While popular history focuses on the physical brutality of beheading, this systematic removal of Anne’s existence represents a deeper violence: the execution of a legacy, an attempt to wipe not only a woman’s body from the world, but her memory. It would take centuries for historians to begin reconstructing Anne’s life from scattered records that survived the purge—letters saved by chance, accounts written quietly, fragments that escaped destruction. But the damage was almost complete.

And the trauma did not end with her. Anne’s execution deeply scarred those forced to witness its aftermath. Her ladies-in-waiting, already terrified of association with the Queen’s alleged crimes, were ordered to clean and prepare her severed head before burial. They did so under watch, in silence, knowing a careless word or visible grief could mark them as suspicious. Several reportedly suffered persistent nightmares for years. At least one woman withdrew entirely from court life, entering a convent, unable to remain in the environment that had demanded such obedience to horror. The psychological aftershocks of Anne’s death rippled outward, poisoning the atmosphere of Henry’s court. Fear replaced loyalty, self-preservation replaced honesty. No one felt safe.

And perhaps nowhere was that cruelty more evident than in the fate of Anne’s child. In the immediate aftermath of the execution, Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth, less than three years old, was formally declared illegitimate, removed from the line of succession, and stripped of status. The child who would one day become England’s most celebrated monarch was, for a time, effectively erased alongside her mother. Court records show that Elizabeth’s household was dissolved almost overnight. She was left without appropriate clothing, attendants, or all recognition befitting royal birth. Her mother executed, her father publicly denying her legitimacy—this was punishment extended by proxy. Anne was dead, but Henry VIII ensured her suffering continued through her child, and that dimension of cruelty is often overlooked.

Most modern dramatizations of Tudor executions fail to capture the full sensory violence of the experience. The scaffold would have reeked of old blood from previous deaths, thick in the warming air of May. Flies hovered constantly. The noise was overwhelming. The crowd, seeded with supporters instructed to cheer, produced a wall of sound designed to intimidate and disorient. Jeers, insults, shouts accusing Anne of witchcraft and adultery filled the space. This was not spontaneous; it was organized public humiliation was a core element of Tudor justice. Death on its own was insufficient; the execution was meant to linger in memory as a warning.

Popular culture often portrays Anne’s final speech as a moment of serene defiance. The reality, preserved in historical accounts, is more restrained and far more tragic. Her words were carefully chosen, shaped by fear for her daughter and by awareness that everything she said would be reported back to the King. Even at the point of death, Anne could not speak freely. Her speech praising Henry as a just and merciful ruler reflects not submission, but constraint. This was not free expression; it was final censorship, the words of a woman who knew that truth itself had become too dangerous to voice.

The sword that ended Anne’s life, especially imported from France, embodied the performative nature of her execution. Henry VIII spared no expense to stage a death worthy of a fallen queen. The executioner reportedly practiced beforehand, perfecting the single blow that justified his high fee. This professionalism reduced Anne’s death to a technical exercise: efficiency over humanity. Anne was not merely killed; she was processed. State-sanctioned execution transformed her suffering into a message, delivered cleanly and decisively. Contemporary accounts note that no English executioner would take on the task, not out of moral hesitation, but because the technique required specialized training. The French sword differed from the English axe: lighter, razor-sharp, designed for a swift horizontal strike rather than a downward chop. This technical detail underscores the artificiality of the entire event. Even the mechanics of death were chosen for aesthetics.

After the sword fell, witness Thomas Wyatt, the poet imprisoned in the Tower and forced to watch the execution of a woman he once admired, later wrote of the “small throat that had so many jewels hanging from it.” That single line captures Anne’s grotesque transformation from adorned Queen to displayed corpse. The executioner lifted her severed head by the hair, a customary gesture intended to demonstrate that the sentence had been carried out. Blood continued to flow as the crowd witnessed the final proof. This image—the raised head, the still-warm body—burned itself into memory. It was the execution’s final act.

No marker was placed above her, no inscription. For centuries her exact burial site was unknown. This absence was deliberate—the removal of even her resting place marked the final stage of Henry’s campaign not merely to kill Anne Boleyn, but to sever her from history itself, and alarmingly, it almost worked.

In the days following the execution, royal propagandists moved quickly. Poets who once praised Anne’s intelligence now produced verses condemning her as corrupt and immoral. Official records emphasized the King’s supposed mercy in providing a skilled swordsman. The spectacle was reframed as kindness; the horror was quietly edited out. This process of sanitization began almost immediately, laying the foundation for centuries of historical distortion.

Perhaps most disturbing to modern audiences is how quickly normalcy returned for the King. The very next day after Anne’s execution, Henry VIII was formally engaged to Jane Seymour. Life moved on; the problem had been solved. Within 2 weeks of sending his second wife to the scaffold, Henry VIII married his third in a quiet ceremony at Whitehall. The speed was not romantic; it was administrative. This brutal efficiency reveals Anne’s execution for what it truly was: not an emotional rupture, but a political solution. Anne had failed to provide a surviving male heir; therefore, she was removed, then replaced. Her death was not mourned; it was processed. The personal tragedy of Anne Boleyn’s execution was fully subordinated to the mechanics of rule and dynasty building. For Henry, her life ended the moment she ceased to be useful.

And even now, this wasn’t the worst of it. The psychological dimension of Anne’s execution extended far beyond the scaffold. For weeks before her death, she was subjected to relentless interrogation, denied consistent sleep, and deliberately isolated from allies. She was kept uncertain, disoriented, and emotionally unmended. Thomas Cromwell, the King’s chief minister and architect of the charges, employed tactics strikingly similar to what modern institutions recognize as psychological torture: disorientation, sleep deprivation, isolation, and the strategic use of false information presented as undeniable truth. By the time Anne reached the scaffold, the goal was not simply to execute her body; it was to ensure that her spirit had already been broken. This was not a trial; it was a mental breakdown campaign, and it succeeded. By execution day, Anne was no longer expected to resist, protest, or destabilize the narrative in any meaningful way. That was the objective all along.

Court records reveal the security measures for Anne’s execution were extraordinary, even by Tudor standards. The Tower garrison was doubled; additional guards were stationed throughout the fortress complex. These precautions were not designed to prevent escape—they were never afraid of that. They were designed to prevent intervention, to ensure no allies could rally support, no sympathetic noble could interfere, no dangerous hesitation could spread through the crowd. The overwhelming show of force served another function as well: intimidation. Anyone who still felt sympathy for Anne was reminded, visibly and unmistakably, that silence was survival. Loyalty was no longer enough; submission was required.

The execution itself was scheduled for mid-morning rather than the usual dawn. This detail mattered. A later hour allowed more people to witness or hear of the event. Though Tower Green could accommodate only a limited audience of nobles and officials, the Tower’s prominence ensured that crowds gathered outside the walls. When the sword fell, church bells across London began to ring. The city itself was made to participate. Anne’s death was not private punishment; it was civic ritual, state power announcing itself through sound, repetition, and spectacle. This transformed her execution into something far larger than personal tragedy; it became political theater. Death was not the point; demonstration was.

Among the most overlooked aspects of Anne Boleyn’s execution is the fate of her alleged accomplices. Five men, including her own brother George Boleyn, were executed just days before her. Their deaths served a crucial function: by killing them first, the Crown established proof of Anne’s guilt before she ever reached the scaffold. Any final statement she made could be dismissed as the protest of a condemned conspirator. This sequencing was deliberate. Six people were eliminated under nearly identical charges, supported by fabricated evidence and coerced testimony. This was not justice gone wrong; it was justice engineered—a coordinated purge, one of the clearest examples of state violence in Tudor England, comparable not in scale but in structure to modern show trials.

Today, Tower Green features a memorial marking the approximate location of Anne’s execution, yet contemporary records indicate that the actual scaffold stood elsewhere within the Tower complex. This geographical uncertainty is symbolic. Anne’s death has been repeatedly relocated, physically and historically, to better fit later narratives—softened, reframed, made acceptable. The romanticized version found in popular culture bears almost no resemblance to the psychological warfare that defined her final days. In May 1536, what happened to Anne was not a tragic misfortune; it was a calculated removal.

The horror of Anne Boleyn’s execution does not reside solely in the moment the sword fell; it lies in the process that led there. This was not simply an execution; it was the climax of a sustained campaign to destroy a woman who had risen too high for the comfort of Tudor society. Anne was not merely killed; she was systematically undone—her reputation dismantled, her achievements invalidated, her lineage threatened, her very existence treated as an error to be corrected.

When we examine the full context—psychological torture, public humiliation, narrative manipulation, and historical erasure—we encounter something far more disturbing than a swift death by a sword from Calais. From a modern psychological perspective, Anne’s execution stands as a textbook example of state-sanctioned gaslighting and reputational assassination. The accusations against her—adultery with multiple men, incest with her brother, poisoning plots against the King—were so implausible they collapse under even minimal scrutiny, yet they were accepted. Why? Because power controls reality when it controls repetition, through coerced confessions, controlled information channels, and the elimination of dissenting voices. The government successfully persuaded much of England that Anne deserved to die. Truth became irrelevant; belief was manufactured. This manipulation of collective perception may be the most terrifying aspect of her death.

Five centuries later, Anne Boleyn’s execution continues to fascinate precisely because it sits at the intersection of personal tragedy and political calculation. Her death was not simply the end of her life; it was a performance designed to justify royal action and permanently rewrite memory. This is not ancient history; it is a recurring pattern, and that is why Anne’s story still matters.

Anne’s ultimate tragedy may be that, despite every effort to erase her, it was her death, not her life, that became her most enduring legacy. By confronting the full reality of her execution, stripped of romance and sanitized myth, we expose uncomfortable truths about power, gender, and historical storytelling. The familiar tale of a disgraced Queen meeting a swift, dignified end conceals something far darker: state power abusing narrative control to justify cruelty. By understanding the psychological machinery behind Anne Boleyn’s execution—how her reputation was dismantled, her voice silenced, her memory threatened—we gain insight into how authority maintains itself through control of bodies and stories. And in the image of Anne’s severed head, momentarily conscious beneath a London sky, we are left with one unmistakable warning: when power controls the story, even truth can be executed.

If this story kept you watching, drop a like and comment your country or city below. I truly love seeing where everyone’s tuning in from, and please subscribe to help this small channel grow. It means more than you know.

News

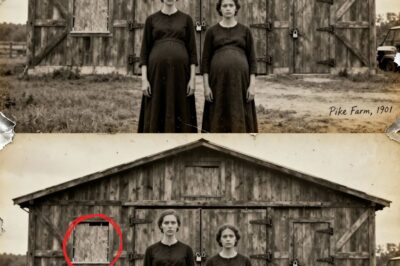

The Breeding Barn Horror: 42 Women Who Vanished Into Evil

The Breeding Barn Horror: 42 Women Who Vanished Into Evil Welcome to history. Picture this: a remote stretch of Missouri…

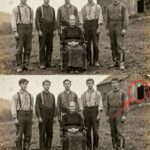

The Mother Who Forced Her 5 Sons to Breed — Until They Chained Her in The “Breeding” Barn

The Mother Who Forced Her 5 Sons to Breed — Until They Chained Her in The “Breeding” Barn Deep in…

A humble mother helps a crying little boy while holding her son, unaware that his millionaire father was watching

A humble mother helps a crying little boy while holding her son, unaware that his millionaire father was watching Under…

What the Ottomans did to Christian nuns was worse than death!

What the Ottomans did to Christian nuns was worse than death! Imagine the scent of ink from ancient parchments still…

The Whitaker Boys Were Found in 1984 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans at All

The Whitaker Boys Were Found in 1984 — Their DNA Did Not Match Humans at All The Blackwood National Forest…

The Pike Sisters’ Breeding Barn — 37 Missing Men Found Chained (Used as Breeds) WV, 1901

The Pike Sisters’ Breeding Barn — 37 Missing Men Found Chained (Used as Breeds) WV, 1901 In the summer of…

End of content

No more pages to load