What Roman Gladiators Did to Captive Women Was Worse Than Death

In 79 AD, deep under Rome’s loudest arena, a 19-year-old Dacian girl named Sabina stood shackled in a pitch-black cell. Above her, 50,000 Romans roared in celebration, cheering the gladiator who had just murdered her brothers. What happened to her over the next three hours became one of Rome’s most aggressively covered-up practices, a ritual so vicious that even Rome’s own historians argued over whether to mention it at all. This is the story Roman senators tried to wipe from the record, the reward that turned a victor into someone who could do almost anything behind closed gates.

Before we go into what unfolded in those underground rooms, hit that like button if you’ve ever wondered what actually happened after the crowd left. Subscribe, because once you hear this, you’ll never look at ancient Rome the same way again. Comment below: did Roman entertainment cross the line, or was this simply the brutal cost of empire? What you’re about to hear comes straight from Cassius Dio’s accounts, confirmed by 2018 excavations beneath the Colosseum, and supported by Senate documents found in the Vatican archive. This isn’t myth; these were the events Rome labeled as “sport,” the reality behind the arena of blood.

All across the empire in the 1st century AD, the Colosseum wasn’t just a building; it was Rome’s monument to dominance. Completed only a year earlier in 80 AD, it was large enough to swallow entire armies. The air always reeked of metal, sweat, and animal stench. The arena floor wasn’t covered in sand for decoration; it was there to soak up whatever poured out of dying fighters and wild beasts. Under that sand lay a maze of tunnels and cages holding Rome’s most valuable assets: the condemned, the captured, and the conquered. Gladiator games weren’t only for entertainment; they were political messaging, religious ritual, and social intimidation rolled together.

When General Marcus Antonius crushed the Dacian uprising in 78 AD, he returned not only with treasure but 847 captives, including 124 noble women. These women weren’t ordinary villagers; they were chieftains’ daughters, warriors’ wives, and priestesses. Rome didn’t just beat their people; it needed to humiliate them so completely that rebellion would never return.

Now, the victor and the condemned met. Gaius Valerius Maximus, 32 years old, stood nearly six feet tall, massive by Roman standards. His entire body was a map of violence—every scar a fight won, a life taken, a crowd thrilled. Born a slave after his father died in debt prison, he had spent 14 brutal years fighting to stay alive. He’d killed 89 men in official combat. His dream was simple: earn the wooden sword of freedom, the Rudis. His worst fear: die anonymously, dragged away on meat hooks like hundreds before him. But this afternoon in August 79 AD, he defeated the Dacian champion right in front of Emperor Titus. His reward followed standard protocol: 500 denarii, a laurel wreath, and first selection among the captiva—female prisoners.

Sabina, with her dark highland hair and pale Dacian skin, stood among 17 other women in a holding cell. Before Rome burned her village, she was engaged to a warrior named Disabilis, killed by Roman troops three months earlier. Now she waited in silence, her world gone, her future erased. She wanted nothing except dignity and death. What she feared most was becoming entertainment for the crowd that had cheered her people’s destruction. That morning, a guard informed her she’d been picked for the afternoon’s event. She didn’t yet understand what that meant. She was about to learn that Rome’s version of mercy was far more horrifying than its cruelty.

This wasn’t about individual lives; it was about psychological warfare. Rome knew physical conquest wasn’t enough. True domination meant breaking a people’s symbols, corrupting their traditions, and proving that even the most protected members of their society—their women—now belonged to Rome. This wasn’t random brutality; it was targeted dehumanization, a message broadcast across every conquered territory: resisting Rome is pointless; losing to Rome is absolute. What unfolded that day would become so notorious that the Senate would soon be forced to act.

At exactly 3:00 p.m., as shadows crept over the blood-soaked arena, the Master of Games descended into the Hypogeum, the underground complex beneath the Colosseum. The corridor reeked of damp stone and panic. He approached Gaius Valerius Maximus with a bronze tablet listing the available spoils. Gaius’s hands still shook from battle, adrenaline still burning through him. “The emperor honors your victory,” the official recited. “By imperial tradition, you’re entitled to the spoils of conquest. Choose.” No one there knew this routine choice, repeated hundreds of times before, would spark a crisis reaching the Senate floor within weeks. The tablet listed the rewards: gold, wine, a night in a proper bed, or Victoria Carnales—the carnal privilege granted to the victor. For a man who owned nothing and could be killed at any moment, this was one of the few times he held any power at all. Roman society didn’t just permit this; it celebrated it. To Rome, the conquered existed to satisfy the conqueror—that was the empire’s logic, perfected over generations.

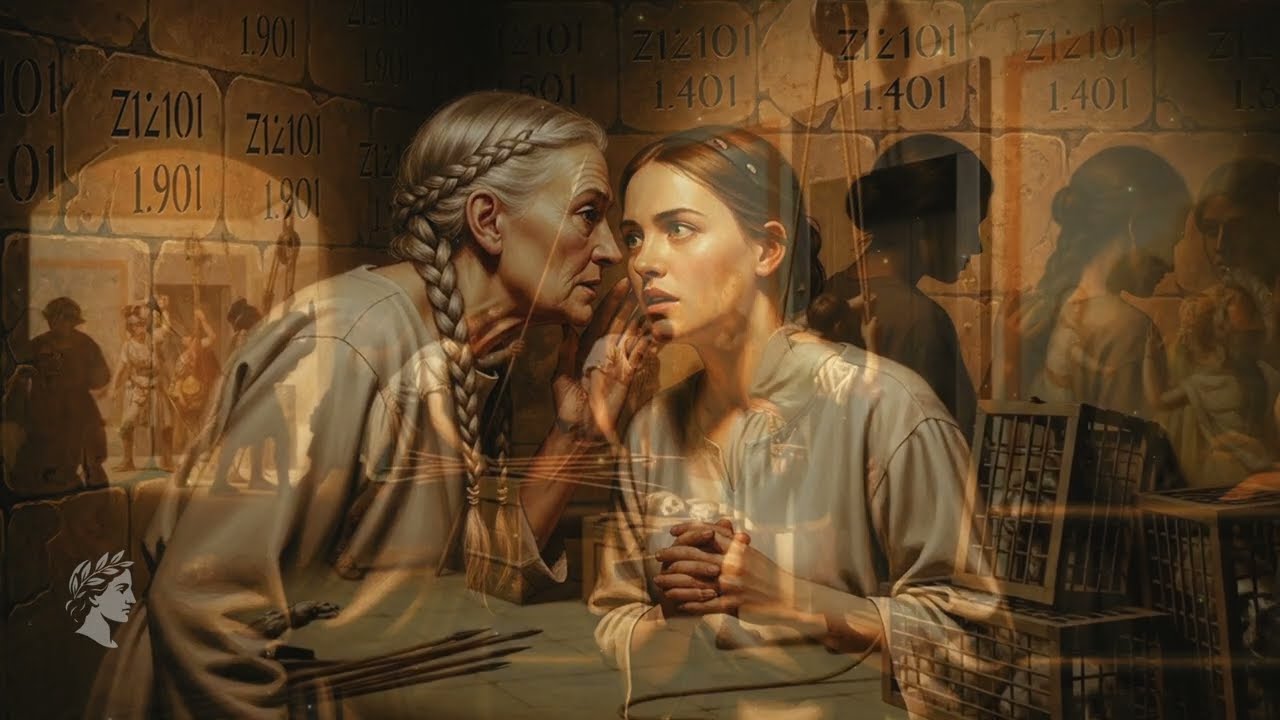

The preparation began inside the women’s holding area. Another kind of preparation was already unfolding. Guards walked in carrying buckets of water—not to drink, but to wash the prisoners. The women were scrubbed down, their hair combed out, and their ripped clothes swapped for plain tunics. Sabina watched the attendants move from one woman to the next, inspecting them and marking details on wax tablets. An older woman, a priestess named Zmoxis, once devoted to the Dacian Sun Temple, whispered the truth everyone feared: “They’re getting us ready, either for the show or for what comes after.” The preparations ended quickly, but somewhere else in the arena, something far worse was being set up—something that would turn a routine act of exploitation into a scandal that future historians would debate for centuries.

Above them, 50,000 spectators filled their seats for the afternoon’s secondary entertainment. Between major gladiator matches, arena officials staged what they called interludes: mock hunts, scripted battles, and what Roman writers politely described as “mythological reenactments,” which often forced condemned prisoners to recreate legends that ended in real deaths. But today’s showcase had a new twist: a theatrical display celebrating Rome’s dominance over barbarian shame.

The arena calls. 20 Dacian women were lifted to the arena through the underground elevator system, an engineering setup designed to send animals, fighters, and props erupting from trap doors. Sabina stepped out into scorching sunlight and an explosion of noise. The roar of the crowd felt like a physical blow. She smelled roasting food from vendors, strong perfume drifting from wealthy seats, and beneath it, the iron smell of dried blood baking on the sand. What should have been a straightforward execution was turned into something calculated for deeper humiliation. The women were lined up as a herald announced their supposed crimes: rebellion, aiding enemies, refusing Roman gods. Then came the twist: they would be forced to fight each other in pairs using wooden swords, dressed in shredded clothing designed to mock them. The winners would be claimed by Rome’s champions; the losers would die.

Wooden swords were handed out. Sabina gripped hers, the rough wood scraping her palm. Across from her stood Kamasicus, Disabilis’s sister, the woman who once taught Sabina to weave and sang at her engagement ceremony. Their eyes locked. The crowd screamed for blood. The Master of Games raised his hand, dropped it. Neither woman moved. The roar shifted; excitement turned to confusion, then rage. “Fight!” the crowd yelled. “Cowards! Barbarians! Trash!” began to rain down: olive pits, food scraps, whatever spectators had in reach. Still, the women didn’t lift their swords. It was the only resistance left to them: refusal. For 90 full seconds, the greatest empire on Earth was publicly defied by two unarmed women standing still. Then the guards stormed in. The stage drama dissolved into real violence. Kamasicus was struck from behind with the flat of a sword, collapsing to the sand. The crowd cheered. Sabina screamed and rushed toward her, letting the wooden sword drop. Both were dragged away, not to execution, but to something the audience found just as entertaining.

The real horror begins in the Hypogeum below. The bureaucratic engine of Roman exploitation kept moving without hesitation. A scribe entered a note into the record: “20 female captives, Dacian origin, processed for post-victory allocation.” Next line: “Two resistant, transferred to private chambers for champion exclusive use.” What came next became Rome’s most polished system of dehumanization: human beings reduced to inventory.

Sabina and Kamasicus were separated, each taken to different rooms—small stone chambers with benches, iron rings embedded into the walls, and doors locking only from the outside. They were clean, organized, and terrifying precisely because everything was planned. This wasn’t improvised cruelty; these rooms were part of the arena’s design, just as intentional as the lion cages or gladiator lifts.

At four, Gaius Valerius Maximus entered Sabina’s chamber. The door opened. Their eyes met. He was still in full arena gear, someone else’s blood smeared across his chest. She was cornered against the far wall, drained, unarmed. Between them stood the full weight of Roman law. He had complete legal power; she had none. She was classified as “spoils,” reward earned through killing. History doesn’t tell us what Gaius thought. Did he see a person? Did he see property? Did he question the system that turned him into both weapon and prisoner? All we know comes from a clerk’s routine report, not from either of them.

Then the unimaginable happened: an act of rebellion. Gaius took off his helmet, set his sword aside, and sat down with his head in his hands. For five long minutes, he said nothing. Sabina remained frozen, bracing for violence that never came. Finally, he spoke in broken Dacian, a language he had picked up from other captives. “What was his name?” he asked. “Mine?” she replied. “No. The man they made you watch die.” “Disabilis.” “No. The one from today.” She shook her head. He sighed. “I killed a Dacian today. Could be family. Your people use that name often.”

What followed wasn’t the assault Rome expected. It was a conversation between two people the empire tried to strip of every shred of humanity. Gaius told her about his father, executed when he was nine. Sabina explained how her home was burned. Two hours passed. Guards checked twice, heard voices, assumed compliance, and walked on.

At 6:00 p.m., Gaius Valerius Maximus made the decision Rome would never forgive him for. He stood, walked to the chamber door, and called for the guard. “This woman is ill,” he declared. “Infected. I refuse the allocation. Send her to the physician.” It was the only loophole the arena system allowed. If a captive was labeled diseased, a gladiator could legally reject her and return her to general prisoner status. The lie was obvious; the guard recognized it instantly. But Roman bureaucracy ran on rigid procedure. Challenging a gladiator’s choice meant paperwork, witnesses, and an inquiry. Accepting the rejection took seconds. And so, Sabina was removed, taken to the medical holding section. Her immediate fate? She still died three days later from a simple infection, the most common killer inside Roman captivity. The medical unit was overcrowded, filthy, and apathetic. The mercy that spared her from one horror delivered her directly into another.

Gaius never saw her again. He fought twice more that month. He won both bouts, and he refused his rewards both times. The empire froze. Whispers spread through the gladiator barracks: “Maximus had gone soft.” “Maximus had joined one of those strange Eastern cults preaching compassion.” “Maximus had been cursed by Dacian witches.” But the truth was simpler: he’d remembered what it meant to be human.

Rome’s point of no return. On September 15th, 79 AD, Senator Quintus Aurelius Sempronicus stood before the Senate with an official complaint. His young nephew, a junior gladiator, had been beaten by his trainer for refusing the customary reward after victory. The nephew claimed Maximus’s example had inspired him. The trainer insisted he was simply enforcing proper Roman values. It was a trivial case, barely worth discussion, except for one thing: it forced Rome’s most powerful men to publicly acknowledge a practice everyone knew existed but no one ever spoke about.

Senate records—the sanitized versions that survived—mention a debate about “the appropriateness of certain customs regarding defeated female captives.” That mild phrase concealed a four-hour political brawl about whether Rome had finally crossed a line even its own senators couldn’t ignore. The conservative bloc, led by Senator Fabius, invoked tradition: “Our ancestors conquered wholly, body and spirit. This forged our greatness.” The reformist faction, Stoic-influenced, more pragmatic, countered: “We are creating martyrs. We are sowing rebellion. Dead rebels are gone, but traumatized survivors carry memories that fuel uprisings for generations.” But the true trigger wasn’t morality; it was political survival. Three provincial governors had recently reported spikes in revolt, each referencing Rome’s treatment of captive women as propaganda for resistance movements. These governors warned that Rome wasn’t intimidating its enemies anymore; it was radicalizing them. The empire was harming itself.

The law that shocked Rome. On October 1st, 79 AD, the Senate passed what historians later labeled the Lex Captivatae—the law of captive women. Its terms were limited but unprecedented: female prisoners of war could not be distributed as public rewards in the arena. Public humiliation of conquered women was banned in official spectacles. Private exploitation still occurred, but the theatrical showcase of it was outlawed. Enforcement was unreliable; many arena managers ignored it or created loopholes. But the principle stood: even Rome had public limits.

Ironically, the law did nothing to free anyone. It only removed the audience. Three months later, Gaius Valerius Maximus finally earned freedom, not for kindness, but for winning five more consecutive bouts. His last recorded act as a free man was purchasing the freedom of a Dacian woman named Kamasicus. The archives identify only her name. Historians strongly suspect she was the same woman who stood beside Sabina on the arena floor.

Imagine Gaius realizing that his single act of defiance saved one woman for a handful of days—nothing more. It changed nothing for the thousands who came before, the thousands who would come after. The machine was too big, too profitable, too embedded in Roman culture. His rebellion was a raindrop falling into an ocean of blood.

Imagine Sabina’s final hours, dying of infection in a cramped cell beneath the grandest structure of her time. Did she wonder if anyone would remember her? Did she imagine that 2,000 years later, archaeologists might find her tag and speak her name aloud again? History’s darkest stories remind us that progress isn’t guaranteed, that civilizations fall morally long before they fall physically, and that every generation must choose between empathy or efficiency. Rome chose spectacle. The cost was measured in lives erased, but the lesson survives in the ruins beneath the arena floor.

The tragedy isn’t merely that Rome was cruel—cruelty defined ancient warfare. The true tragedy is that Rome industrialized it, turned it into entertainment, standardized it with paperwork, supply lines, and architectural planning—a system so complete that people disappeared into it without leaving a trace, except scratches on stone.

In 2018, archaeologists from the University of Rome, led by Dr. Cocca Isabella Fortunato, excavated a forgotten section of the eastern Hypogeum. What they found never appeared on tourist brochures: a cluster of small chambers with iron restraints built directly into walls, drainage channels cut into stone floors, scratch marks carved by desperate hands, pottery fragments used to transport water or food, remnants of bedding materials compressed by years of weight. Carbon dating confirmed the rooms were from the original 80 AD construction, meaning they were built intentionally, not added later. Six bronze tags were recovered, stamped with the word captiva and dates spanning 79–82 AD—the exact years of the Dacian suppression.

These findings matched textual evidence. Cassius Dio’s later writings described “allocation chambers” for conquered women. Seneca’s earlier letters alluded vaguely to the practice without detail. Tacitus, normally graphic, was conspicuously silent, implying even he found it too repulsive to record plainly. Historians debate frequency. Some argue it was rare, reserved for major triumphs. Others point to the specialized construction, abundant evidence, and multiple sources, arguing it was routine. The truth lies somewhere in between: not constant, but common enough to design infrastructure for.

Romans treated gladiators like ancient celebrities, but with a dark twist. Elite women bribed guards to meet them. Engraved lamps and wall paintings show gladiators posing naked with weapons. Their sweat and blood were sold as aphrodisiacs; some women even drank it as a fertility cure. The same society that worshiped these men also fed them into machines of death and rewarded them with human beings. Historical accounts describe nocturnal entertainments after major games, where wealthy patrons mingled with gladiators and slaves. Women captured in war were paraded as trophies, sometimes forced to reenact myths involving gods like Jupiter or Mars before being used as gifts.

Prisoners forced to strip during triumphal parades, victims tied to stakes to imitate myths before execution, enemy queens paraded publicly before being handed to generals. None of it was accidental. It was a message to the world: Rome owns your past, present, and future. Gladiator games weren’t random; they were part of the munera (obligations) owed to the public. Patrons who hosted games had incentives to increase spectacle. Humiliation of captives became a selling point.

The 19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen called this “Rome’s most efficient machine of dehumanization.” What he meant was simple: Rome didn’t just conquer bodies; it conquered identity, memory, and meaning. The fact that we still debate these events today shows how deep the scars run. The 2000 film Gladiator barely whispered about this reality, hinting at it only in shadows, and modern scholars still argue whether discussing these practices exposes Roman brutality responsibly or simply risks sensationalizing it. But it matters because it shows exactly how a civilization can defend cruelty through laws, customs, and entertainment. Rome wasn’t the only empire capable of horrifying acts, but it perfected the ability to normalize them, to turn violence into ritual and transform screams into crowd-pleasing spectacle.

The deeper truth is this: the line separating civilization from barbarism has never been measured by marble temples, paved roads, or towering arches, but by how a society treats those with no power at all. Rome engineered aqueducts that survived 2,000 years, yet at the same time built chambers beneath its stadiums where human beings were violated as casually as props in a performance. Its brilliance and its moral emptiness existed side by side without contradiction.

It also reveals how power distorts everyone it touches. Gaius was both victim and tool, enslaved, controlled, forced to kill for survival, yet granted authority over someone even more helpless than him. The system twisted ordinary people into instruments of cruelty and turned human suffering into entertainment when it should have stirred empathy instead of applause. It warns us about the danger of using tradition as moral justification. “Our ancestors did it” became Rome’s answer to every ethical question, until habit replaced humanity and atrocity became routine. And it raises questions we still struggle with today: What other buried horrors lie beneath the monuments we admire? How many tourist attractions sit on layers of forgotten misery? When does confronting the past become necessary, and when does it cross into exploitation?

Think of Sabina’s final moments, dying of infection in a cramped cell beneath the grandest structure of her time. Did she wonder if anyone would remember her? Did she imagine that 2,000 years later, archaeologists might find her tag and speak her name aloud again? History’s darkest stories remind us that progress isn’t guaranteed, that civilizations fall morally long before they fall physically, and that every generation must choose between empathy or efficiency. Rome chose spectacle. The cost was measured in lives erased, but the lesson survives in the ruins beneath the arena floor.

And so, a gladiator’s victory became permission for cruelty. A routine reward became one of Rome’s most carefully buried scandals. Hundreds of Dacian captives disappeared into bureaucratic lists, and one young woman named Sabina survived only because a single fighter made an unusual choice—a choice that changed nothing, except proving humanity could still flicker even in Rome’s darkest machinery. If this story unsettled you, subscribe, because uncomfortable truths matter far more than comforting myths. Tell us in the comments what disturbed you most: the calculated nature of the exploitation or Rome’s efficiency at making it routine. Remember, history’s darkest secrets often hide beneath civilization’s greatest monuments. The blood on the sand wasn’t always from battle. Sometimes it came from innocence turned spectacle, from power without restraint, from the moments humanity looked away while cruelty received applause.

News

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

Caligula’s 7 Hidden Palace Rituals Rome Tried to Erase

Caligula’s 7 Hidden Palace Rituals Rome Tried to Erase Rome, 39 CE, an imperial banquet. Imagine sitting at a table…

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22)

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22) Welcome to this journey through one of the…

I woke from the coma just in time to hear my son whisper, “Once he di.es, we’ll send the old woman to a nursing home.” My bl00d froze—so I let my eyes stay shut. The next day, they came to the hospital searching for me… but my wife and I were already gone. Abandoned by the very people I raised, I quietly sold everything. Now, in a foreign country, our new life begins… but so does something else.

I woke from the coma just in time to hear my son whisper, “Once he di.es, we’ll send the old…

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22)

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22) Welcome to this journey through one of the…

End of content

No more pages to load