U.S. Marine snipers couldn’t hit their target — until an old veteran showed them how.

“Is this a joke?” barked Staff Sergeant Miller, his voice piercing the tense silence. He wasn’t looking at his Marines. His gaze was fixed on the old man standing motionless behind the line of fire. “Do you even know where you are, old man?” Dean Peters, 82, dressed in worn jeans and a faded work shirt, didn’t react.

He held a long, cloth-wrapped object in his hands, his back relaxed, but his gaze piercing. Nothing escaped him. He observed the flags on the firing range, each telling a different story. A chaotic symphony that the sophisticated equipment of the young Marines was unable to decipher. “This is an active firing range for Special Forces reconnaissance snipers,” Miller continued, stepping toward him.

Miller was the archetype of the modern warrior: athletic, self-assured, and equipped with the latest tactical gear. His ballistic calculator was strapped to his wrist. “A piece of technology worth more than Dean’s car. Civilian presence is strictly prohibited. I order you to leave immediately.” Dean’s gaze flicked from the windswept terrain to the artillery sergeant.

His eyes, a pale blue the color of a winter sky, possessed a depth that seemed to absorb Miller’s aggression without reflecting it. “The wind is fickle today,” Dean said in a deep, calm voice. “There isn’t just one wind, there are three.” Miller let out a small, incredulous laugh. A few young Marines shifted in discomfort.

They had been working on it all morning, their state-of-the-art Kestrel anemometers providing contradictory readings. Their ballistic computers spit out firing solutions that repeatedly proved useless. The target, a small steel silhouette more than 1,700 meters away, could just as easily have been on the moon. The exercise was designed to push them to their limits in order to simulate the impossible firings required in the mountains of Afghanistan or the vast deserts of Iraq.

At that precise moment, the impossible was winning. Three wins, right? Miller chuckled, arms crossed. “Look, Dad. I appreciate folk wisdom, but we have the equipment for this. We’re dealing with the Coriolis effect, drift due to rotation, and barometric pressure that changes every five minutes. It’s a bit more complex than lifting a wet finger.”

Dean simply shrugged, without aggression. “Your computer can’t detect the thermal updraft forming over those rocks at 1,000 meters, nor the downdraft in that ravine to the left. The flag on the target is misleading you. It indicates a left-to-right direction, but the valley channels a current in the opposite direction, just on that side.”

“You’re trying to solve one problem, but the bullet has to go through three.” One of the young Marines, Corporal Evans, lowered his observation binoculars. He had watched the Mirage boil and slosh all morning. There was a strange logic to what the old man was saying. The heat waves were spreading in different directions and at different distances, but he wouldn’t dare say it out loud.

Definitely not to Gunny Miller. Miller’s face tightened. His professional pride took a hit. This old gardener, whom he’d seen mowing the lawn near the firehouse, was giving him long-range shooting lessons. “And I suppose you could do better,” he said sarcastically. He pointed to the object wrapped in a long piece of cloth that Dean was holding.

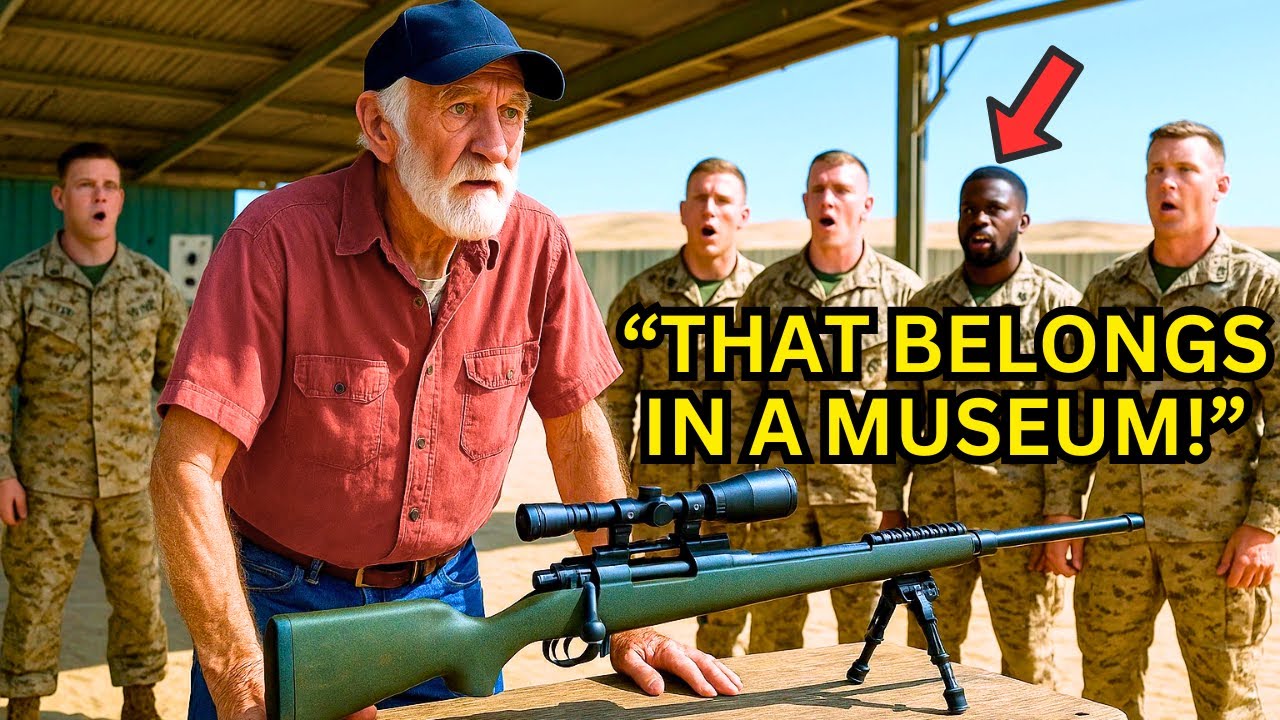

“What exactly do you have here?” “Grandpa’s squirrel rifle.” Slowly, deliberately, Dean began to unpack the object. It wasn’t a modern tactical rifle with a carbon fiber stock and an adjustable chassis. It was a weapon made of wood and steel. The walnut stock was dark, weathered by time and linseed oil, marked and dented, bearing witness to a long, hard life. The mechanism was a classic bolt-action system, and the scope mounted on it was simple, without the complex turrets and reticles of modern optics. It was an M40, the rifle of another era, a relic. The snipers stared at it. This rifle was a legend, a model they had only seen in museums or in period photographs from the Vietnam War.

Seeing one here, in the hands of this old man, was surreal. Miller let out an incredulous laugh. “Are you kidding? You really think this antique can hit the target, let alone touch it? The barrel’s probably worn down to the threads.” He pointed to the rifle’s stock, showing a deep nick near the bolt. “Just look at this.”

“It belongs in a museum. You’re going to hurt yourself.” The moment Miller pointed at the worn wooden stock, the oppressive heat of the shooting range vanished from Dean’s mind. The world turned green and humid. He was no longer 82 years old, but 19. The air was no longer dry and dusty. The stifling humidity of the Vietnamese jungle was suffocating.

The stench of mud and decay filled his lungs. A light, warm rain fell, clinging his uniform to his skin. He lay face down in a nest of ferns, perfectly still, his heart beating slowly and steadily against his ribs. He held the same rifle, its walnut stock glistening with rainwater and mud. The dent Miller had mocked was…

A piece of mortar shrapnel, landed too close just minutes before. Through his rudimentary telescope, he spotted a small clearing about 800 meters away. An enemy machine gunner was taking up a position, a position that would pin down an entire section of his comrades. His breathing was the only thing in the world he could control.

He half-exhaled and stared at the reticle as it stabilized. The wind, even here, was deceptive, swirling through the triple-canopy jungle. But he didn’t need a flag. He watched the slanting rain, the rustle of a leaf on a branch. He squeezed the trigger. The memory faded into the muffled thud of the shot, a sound swallowed by the jungle.

Back at the shooting range, the sun beat down. Dean’s gaze returned to Staff Sergeant Miller. The old man’s expression hadn’t changed, but something inside him had settled, become heavier. He had heard the jeers, but they hadn’t affected him. The rifle wasn’t a museum piece. It was a part of him. Corporal Evans had watched the whole scene, a knot of worry tightening in his stomach.

He was a good Marine. He respected the chain of command, but also his seniors, and the gunnery sergeant’s blatant disrespect seemed unacceptable to him. Besides, there was something about this old man that seemed familiar. A vague sense of déjà vu. He’d seen him around the base for years, always quiet, always discreet.

But he’d also heard stories, whispers from the old sea dogs at the gun shop, legends about that unassuming guard who’d once been someone. Miller was now fully committed to his path. His own failure at the shooting range had ignited anger within him, and Dean was the perfect target. “I won’t ask you twice, sir. Restricted area.”

“You’re a civilian and you’re a danger. Put down that weapon and move away from the line of fire.” Evans knew he had to do something. He couldn’t confront the sergeant major directly, but he could make a phone call. “Sergeant Major,” he said, standing up. “The reticle on my spotting scope is blurring. I think the nitrogen seal failed because of the heat.”

“I want to take it to the armory’s repair shop.” Miller, distracted and annoyed, waved his hand away, as if dismissing the question. “It doesn’t matter. Get it fixed. We’re not packing up until we’ve hit the target.” Evans grabbed his scope and ran away from the firing line, his heart pounding. He didn’t go to the repair shop. He hid behind a row of Humvees, pulled out his phone, and found the number he was looking for.

The phone rang twice before a gruff voice answered. “Sergeant Major Phillips speaking. Master-at-Arms, this is Corporal Evans from Charlie Company. Evans, what can I do for you? Don’t tell me you’ve broken another $30,000 scope!” No, Master Gunner, I’m at the WhiskeyJack shooting range with Sergeant Miller’s team.

Evans lowered his voice, glancing back at the firing line. “You won’t believe this. Staff Sergeant Miller is giving that quiet old man who maintains the field a right telling-off.” There was a silence on the other end of the line. “The old man with the limp. That’s him. But Master Gunner, he brought a rifle, an old M40.”

And the sergeant major is about to have him arrested for trespassing. Evans hesitated. He called him Dean Peters. The silence on the other end of the line was sudden and complete. It lasted a good five seconds. When Sergeant Major Phillips spoke again, his voice was completely different. It was tense, urgent, and devoid of all its previous harshness.

My boy, are you telling me Dean Peters is at that shooting range right now? Yes, Master Gunner. Stay where you are, Evans. Under no circumstances should you let Staff Sergeant Miller touch him. Do what you have to do. I’ll make a call. Keep them where they are. The line went dead. Evans stood behind the Humvee, a new kind of dread creeping down his spine.

He felt as if he’d pulled the pin on a grenade. Colonel Marcus Hayes, commander of the Marine Raiders Training Center, was in the middle of a budget meeting, a meeting that made him long for the relative simplicity of a gunfight. His aide, a young captain, knocked and entered without waiting for a reply.

His face was pale. “Sir, please excuse the interruption, but there’s a priority call on your direct line from Staff Sergeant Phillips at the Main Armory. He told me to tell you it’s a classified protocol.” Colonel Hayes frowned. No such protocol existed, but he knew Phillips, the gunnery master, knew more about the Marine Corps than most officers would ever learn. He wasn’t exaggerating. Hayes picked up the phone. “Hayes here.” He listened, his posture gradually stiffening, his knuckles whitening from the pressure of the receiver. His conversation was brief, terse, and growing increasingly intense. “What?” “At Whiskey Jack, with Sergeant Miller’s team. Who’s there? Repeat that name.”

A long silence followed. The colonel’s eyes widened, a look…

A look of shock crossed his face. “Are you absolutely certain?” He listened for another moment, then abruptly hung up with a click that startled the captain. He stood up, his chair scraping loudly on the floor. The budget meeting was forgotten.

“Captain!” he barked in a low, authoritative voice that had no effect on the captain. “Bring my vehicle here immediately. Tell the base sergeant major to meet me at the main entrance in two minutes. We’re leaving for the Whiskey Jack shooting range. Sirens and flashing lights on.” Back at the shooting range, Staff Sergeant Miller had reached his breaking point. The old man’s absolute refusal to be intimidated was more infuriating than any discussion. “That’s enough!”

“I’ve had enough of this circus!” Miller declared, his voice booming. He took another step toward Dean, encroaching on his personal space. “Sir, I order you to leave this military installation immediately.” “If you refuse, I will arrest you myself and have the military police escort you to a holding cell.”

To emphasize his point, he firmly placed his hand on Dean’s shoulder, pulling him away from the line of fire. “You’re disrupting a live-fire exercise and endangering my Marines. That’s it.” Dean didn’t move. He didn’t even flinch. He simply stared at the young Marine’s hand on his shoulder, then looked up at his face.

His gaze expressed neither anger nor fear. It was rather pity, a profound sadness, a weariness tinged with sorrow. Then the first siren wailed. It sounded like the distant song of a whale, a sound so incongruous on this isolated firing range that everyone stopped. All eyes turned toward the long dirt road leading from the main base.

A cloud of dust rose, growing larger by the minute. It wasn’t a single vehicle. It was a convoy. Two black command Humvees and a military police car. Their emergency lights, flashing silently in the blazing sun, hurtled toward them at a speed that tore up the road. The convoy screeched to a halt just meters from the line of fire, the doors opening before the vehicles had even come to a complete stop.

The first to emerge was Colonel Hayes. His uniform was immaculate, his face frozen in cold fury. Right behind him stood the base sergeant major, a man with the bearing of a granite statue. A deathly silence fell over the firing range. The snipers who had witnessed the confrontation between their sergeant major and the old man suddenly straightened up.

Staff Sergeant Miller froze, his hand still on Dean’s shoulder, a mixture of confusion and burgeoning horror etched on his face. Fifteen years of service in the Marine Corps, and he’d never seen the base commander and the sergeant major arrive anywhere, let alone on a firing range, with such speed and intensity. Colonel Hayes completely ignored Miller.

His eyes were fixed on Dean. He stepped forward purposefully, his boots crunching on the gravel, and stopped dead in his tracks in front of the old man. He saw Miller’s hand on Dean’s shoulder, and his eyes narrowed into menacing slits. Miller jerked his hand away, as if he’d been burned. Then, the unthinkable happened. Colonel Hayes, commanding officer of the Marine Corps’ most prestigious training center, executed a military salute of exceptional precision and clarity, the most impressive Miller had ever seen.

Back perfectly straight, arm outstretched, gaze filled with absolute respect. “Mr. Peters,” the colonel’s voice boomed through the silence of the firing range. “Sir, please accept my apologies for the conduct of my Marines. Nothing justifies the disrespect you have suffered today.” A murmur of horror rippled through the line of young snipers.

Their sergeant major seemed petrified. His jaw was slack, his face pale. In less than thirty seconds, he had gone from absolute master to the target of a colonel’s wrath. The sergeant major approached Miller and spoke to him in a low, icy voice.

“Sergeant Major, what was the matter with you?” Colonel Hayes maintained his salute until Dean nodded slowly, almost wearily. Only then did the colonel lower his hand. He turned to the stunned group of snipers. His voice was cold and harsh, imbued with authority. “Marines,” he began, in a tone that left no room for misunderstanding.

You failed this test all morning because you believe the technology attached to your rifles makes you snipers. You were humiliated by a mile of air. And in your frustration, your leader chose to pick on a man he isn’t even worthy of honor.” He pointed at Dean. “For your instruction, allow me to introduce you to the man you disrespected.” This is retired Master Sergeant Dean Peters. He literally wrote the doctrine on high-angle, crosswind fire, a doctrine you all fail to apply. In Vietnam, we didn’t have a name for enemy snipers, but the enemy did. They called him the Phantom of the AA Valley. The colonel’s gaze swept over the young faces, each now a mask of…

We are in shock

Mr. Peters holds the third-longest confirmed shot in Marine Corps history. A successful shot in the middle of the monsoon season, with winds that would seem like a mere breeze today. And he made that shot. The colonel paused, letting his words resonate with the maximum impact of that same rifle your artillery sergeant major had just described as a museum piece. He turned to Dean. Mr. Peters.

Sir, would you be so kind as to show these men how to do it? Dean nodded slowly. He walked over to the empty firing position, not with the brisk efficiency of young Marines, but with a slow, deliberate economy of movement. He lay down on the mat, settling behind the old M40. He didn’t use a bipod.

He rested the butt of his rifle on his old, worn backpack. He paused for a few moments, breathing deeply, his eyes scanning the entire length of the firing range. “Your computers are searching for data,” he said in a calm, instructive voice to the silent Marines. “You have to look for the signs. You see that shimmer above the rocks 1,000 meters away? It’s blowing from right to left. It’s a thermal current.”

But look at the grass on that embankment 1,500 meters away. It’s barely moving and leaning towards you. The wind is blowing on itself. The target flag is way down in the distance, caught in the main current. It’s a feint. You have to aim for an opening in the wind.” He made a few discreet clicks on the elevation and windage adjustment knobs of his scope.

Simple, precise adjustments, the fruit of a lifetime of observation. He rested his cheek against the worn wood of the stock, a position he had adopted thousands of times. He inhaled deeply, exhaled halfway, and silence fell over the shooting range. The sharp click of the old M40 echoed, a nostalgic sound from another war.

All the spotting scopes in the shooting range were now trained on the distant target. For two and a half minutes, breath held… For a few seconds, there was only the whisper of the wind, then, faint but unmistakable, a sound pierced the kilometer of shimmering air. The clear, crisp sound of a copper-jacketed bullet striking hardened steel.

A direct hit to the center. A wave of spontaneous applause and cheers erupted from the young Marines. The morning’s tension dissipated, and it was a demonstration of absolute respect. Colonel Hayes shook his head, a faint smile of admiration on his lips. Then he turned his face, now cold again, toward Staff Sergeant Miller. “Staff Sergeant,” he said in a dangerously low voice.

“Your arrogance blinded you. Your primary duty is not only to be a good marksman, but to train others. You had a living legend, an invaluable resource, right there, offering you his knowledge for free, and you treated him like an intruder. You failed.” Miller froze, his face contorted with shame and regret. “Sir, there are no excuses.”

“There are no excuses,” the colonel confirmed. “You and…” Your entire team will report for a week of refresher training in wind estimation and field techniques. Your instructor will be Mr. Peters, if he accepts the assignment. Dean struggled to his feet, his old joints protesting softly.

He approached Miller, who was avoiding his gaze. He placed a gentle hand on the young Marine’s shoulder, the very same hand Miller had angrily grabbed moments before. “The equipment helps,” Dean said calmly, without a trace of triumph. “But it doesn’t replace what’s inside me.” He tapped his temple with a calloused finger.

“The wind doesn’t care about your computer, Staff Sergeant. It just is. You have to learn to listen to it, not just measure it.” As Dean held the old rifle, its weight familiar to him, another memory came back to him, brief and warm. He was a young corporal, barely twenty years old. A seasoned staff sergeant, a chosen reservoir veteran, handed him this very rifle. The stock was newer, the barrel bluing darker. “It’s nothing special, son,” the old man had said, his voice raspy. “It’s heavy, and it’ll kick you if you don’t hold it properly. But it will never lie to you. The wind, the heat, the jungle—they’ll all lie to you. You just have to learn its language.”

Learn to trust what she tells you. The rifle wasn’t just a tool. It was a legacy. Knowledge passed down through generations of sharpshooters. In the weeks that followed, the atmosphere at the Whiskey Jack shooting range changed. Every morning, an elite team of Marine snipers, including the deeply humble Sergeant Miller, sat in a semicircle on the dusty ground.

They weren’t behind their high-tech rifles. They were listening. In the center of the circle was Dean Peters, holding a simple blade of grass, explaining how its rustling could reveal more than a $10,000 weather station. He taught them to read the mirage, not as an obstacle, but as a road map of the sky. He taught them patience, observation, and an intuition that had been eliminated by an over-reliance on technology.

The Marine Corps has officially added a new section to its advanced sniper training program.

They relied on his teachings. It was called Peters’ Doctrine of the Wind. About a month later, Miller, dressed in civilian clothes one Saturday afternoon, was in the local hardware store looking for parts for his automatic sprinkler. He spotted a familiar figure in the next aisle, examining packets of tomato seeds.

“It was Dean.” Miller took a deep breath and approached. “Mr. Peters,” he said softly. Dean looked up, a friendly, fatherly smile on his lips. “Grandpa, how are your tomatoes?” Miller was surprised. “Sir, I saw you planting them last week. You planted them too close together. They’re going to choke each other out,” Dean said, winking at him. He hadn’t missed a thing.

Miller felt a wave of humility that was no longer painful, but purifying. “Sir, I just wanted to thank you for everything. You’ve taught me more in this week than in five years of service.” Dean simply nodded, his smile genuine. He reached out and patted Miller on the shoulder. “You’re a good Marine, son.”

You were just trying to read the book instead of looking at the weather. He held up the packet of seeds. It’s all about paying attention to the little details. He turned to leave, then stopped. Keep listening, son. Keep listening. Miller watched him go. A quiet old man who had reminded a whole generation of soldiers that the most powerful weapon is not the one you hold in your hands, but the wisdom you carry within you.

If Dean Peter’s story of quiet courage and timeless wisdom has inspired you, click “Like,” share this video with someone who needs it, and subscribe to Veteran Valor to discover more stories of unsung American heroes.

News

GOOD NEWS FROM GREG GUTFELD: After Weeks of Silence, Greg Gutfeld Has Finally Returned With a Message That’s as Raw as It Is Powerful. Fox News Host Revealed That His Treatment Has Been Completed Successfully.

A JOURNEY OF SILENCE, STRUGGLE, AND A RETURN THAT SHOOK AMERICA For weeks, questions circled endlessly across social media, newsrooms,…

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own

The Horrifying Legend of the Harper Family (1883, Missouri) — The Clan That Ate Its Own The year was 1883,…

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case

The Reeves Boys Were Found in 1972 — What They Confessed Destroyed the Case There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist…

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart

“Play This Piano, I’ll Marry You!” — Billionaire Mocked Black Janitor, Until He Played Like Mozart “Get your filthy hands…

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything

The Grayson Children Were Found in 1987 — What They Told Officials Changed Everything There’s a photograph that shouldn’t exist….

Ana Lucinda: The slave who hid the son she had with her master so that he could be born free.

Ana Lucinda: The slave who hid the son she had with her master so that he could be born free….

End of content

No more pages to load