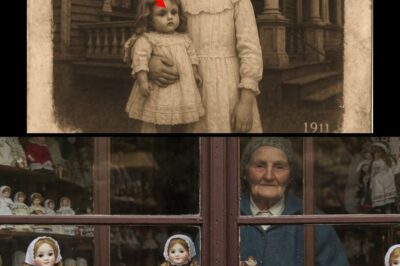

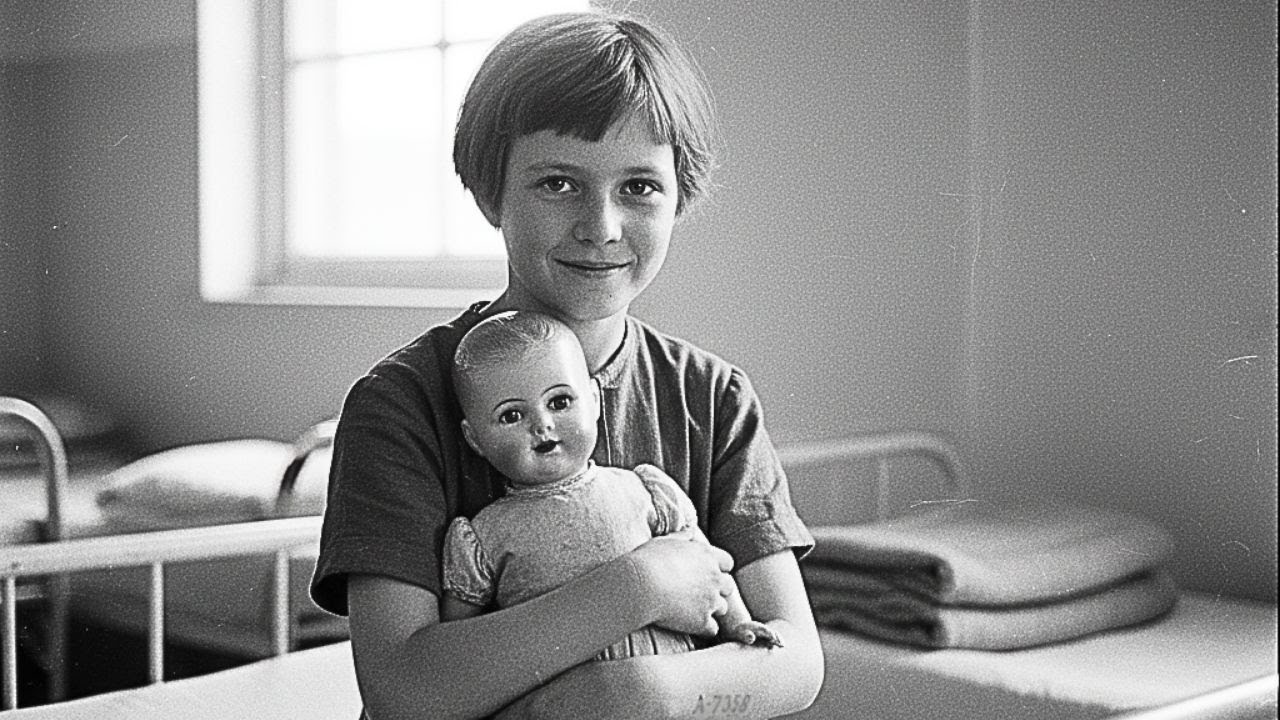

This 1945 photo showing a little girl holding a doll looked cute — until a zoom revealed her hand.

It’s an image that, at first glance, evokes a tenderness tinged with melancholy. It’s May 1945, a few weeks after the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. A little girl, her hair cut short, wearing a dress too big for her frail figure, sits on a metal cot. In her arms, she clutches a porcelain doll almost as big as she is. She attempts a shy smile for the camera.

For nearly eight decades, this photograph lay dormant in the archives, labeled simply: “Unidentified surviving child, May 1945.” She was just one face among thousands, a silent testament to the horrors of war and stolen innocence. But in August 2024, everything changed.

Dr. Sarah Lieberman, a senior researcher at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, was digitizing a new collection of photos when she came across this image. Something about it intrigued her. Zooming in to 400% on the child’s left hand, her breath caught in her throat. There, on that tiny forearm, a series of indelible numbers appeared: A-7358.

It wasn’t just a mark. It was a tattoo from Auschwitz.

The Impossible Anomaly

For a historian, seeing such a tattoo on such a young child is a terrifying anomaly. The vast majority of children arriving at Auschwitz were sent directly to their deaths. They were not registered, not tattooed. For a six-year-old girl to bear this number meant that she had been through hell, survived the initial selection, endured the inhumane conditions of the camp, and survived long enough to be transferred to Bergen-Belsen before liberation. It was a statistical miracle, a shocking exception.

Dr. Lieberman knew she had stumbled upon the beginning of an extraordinary story. But who was A-7358? Nazi records, often destroyed or incomplete, provided only a registration date: May 28, 1944. No name. Just a number and a date. A void.

What followed was a veritable detective investigation through time and history. Sarah contacted archives in Germany, Israel, and France. She pored over transport lists, post-war orphanage registers, and Red Cross documents. Each dead end was frustrating, but the image of that little girl holding her doll compelled her to continue. She had to have a name.

The Decisive Breakthrough

After weeks of painstaking searching, light came from a dusty document in the Bergen-Belsen archives. A handwritten list mentioned a child: “Number 47, female, approximately 6 years old, Auschwitz tattoo 7358. Name unknown. Does not speak. Placed in the care of UNRRA in June 1945.”

The trail then led to Paris. A home for Jewish orphans had taken in hundreds of survivors after the war. And there, in an admissions register dated June 22, 1945, the miracle occurred. Number A-7358 finally had a human face: Hannah Goldberg.

Hannah came from Munkács, Hungary. She had lost her parents and brother upon their arrival at Auschwitz. Alone in the world, traumatized, and suffering from tuberculosis, she no longer spoke. The notes of the caregivers at the time described a terrified child who refused to let go of one thing: her doll. The same doll visible in the photograph.

Find Hannah

Identifying the child was only the first step. Sarah Lieberman wanted to know if Hannah had survived the postwar period. Had she been able to build a life for herself after such a start? Genealogical research revealed that Hannah had been adopted by Eva, the nurse who had cared for her in Paris. Together, they had emigrated to New York in 1949. Hannah had married, become Hannah Rosenberg, had children, and then grandchildren.

In 2024, records indicated that Hannah was living in a retirement home in Florida. She was 84 years old.

With a pounding heart, Sarah arranged a meeting, not without apprehension. Bringing up memories of the Holocaust is a delicate matter. But Hannah agreed.

The Encounter: “It’s me”

On October 15, 2024, in a sunny Florida common room, past and present collided. Sarah handed a tablet to the bright-eyed old woman. On the screen, the high-resolution photo.

Hannah stared at the picture. The silence in the room was heavy with emotion. Her daughter held her hand. “That’s me,” Hannah whispered, tears streaming down her wrinkled cheeks. “I hadn’t seen a picture of myself from that time in 79 years. I don’t remember my parents’ faces, but I remember that moment.”

Then she asked a question that shook Sarah: “Do you want to see her?”

Hannah stood up, leaning on her cane, and went to a cupboard. She took out a carefully wrapped box. Inside, protected by tissue paper, lay the doll. The paint was chipped, the dress yellowed with age, but there it was. Intact.

“I called her Hope,” Hannah confided. “She was the first gift I received after hell. She reminded me that goodness still existed in this world.”

More than just a number

Hannah Goldberg Rosenberg’s story is much more than a historical anecdote. It is a resounding victory of life over death. The Nazis had tried to reduce her to a series of numbers, to erase her from the face of the earth. They tattooed her arm to dehumanize her.

But today, Hannah is not a number. She is a mother, a grandmother, and a great-grandmother. Her family numbers more than 30 members, all descendants of that little girl who died broken on a cot.

In a poignant scene recounted by Sarah, Hannah’s six-year-old great-granddaughter—the same age as Hannah in the photo—touched the faded tattoo on her great-grandmother’s arm. “Does it hurt?” the child asked. “Not anymore,” Hannah replied gently. “Now it’s just a reminder that I survived.”

Hannah decided to donate her precious “Hope” doll to the museum. It will now sit next to the 1945 photograph, tangible proof that even in the deepest darkness, a small glimmer of humanity can save a soul.

This discovery reminds us of the crucial importance of looking beyond the surface. Behind every archival photograph, behind every anonymous face in history, lies a life, a name, and sometimes, a miracle just waiting to be told. Thanks to the tenacity of a researcher and the resilience of a survivor, A-7358 has its name back, and the world has a heroine back.

News

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

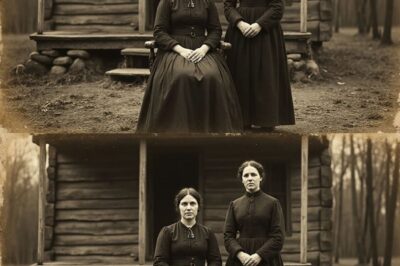

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

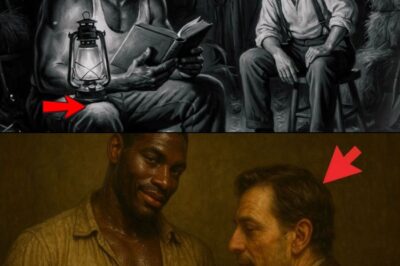

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load