The Winfield Kids Were Found in 1879 — What They Explained Didn’t Sound Human

There are stories that shouldn’t be told, not because they aren’t true, but because once you hear them, they change the way you see everything that came before. This is one of those stories. In the autumn of 1879, three children walked out of the woods near Winfield, Kansas. They had been missing for 11 days.

When the town’s people found them standing at the edge of Miller’s Creek, barefoot and silent, something was wrong. Not with their bodies. Those were intact, unharmed, barely even dirty. It was their eyes, cold, distant, like they’d seen something that had hollowed them out from the inside. The children wouldn’t speak for 2 days. When they finally did, what came out of their mouths didn’t sound like children at all. They spoke in unison.

They described a place that shouldn’t exist, and they gave instructions, rules they called them, that their parents were too terrified to ignore. Within a year, four adults in Winfield were dead. Within 5 years, the town had nearly emptied, and by 1900, the Winfield incident had been scrubbed from almost every record, buried so deep that most historians will tell you it never happened. But it did.

This is the story of the Winfield children. What they found in those woods, what found them, and why more than a century later, there are people who still refuse to say their names out loud.

It begins on September 14th, 1879, a Saturday, the kind of late summer day where the air smells like dust and dry grass and the horizon shimmers with heat. Three children, Eliza Corbett, age nine, her brother Thomas, age seven, and their cousin Nathaniel Puit, aged 10, told their mothers they were going to play near the creek.

By sundown, they hadn’t come home. By midnight, the entire town was searching. They found nothing. No footprints, no torn clothing, no signs of struggle. It was as if the earth had opened up and swallowed them whole. The search parties went out every day for 11 days straight. Farmers, shopkeepers, the sheriff, even the circuit preacher.

Everyone in Winfield and the surrounding townships joined in. They combed the woods along Miller’s Creek, checked every abandoned homestead, every root cellar, every dry gulch within 10 miles. They dragged the creek twice. They questioned drifters, checked the rail lines, sent telegrams to neighboring counties. Nothing.

On the fifth day, Eliza’s mother, Margaret Corbett, stopped eating. She would sit on her porch from dawn until dark, staring at the treeline, her lips moving in silent prayer. Thomas’s father, Samuel, organized a night search with torches. Convinced the children had gotten lost and were hiding, too frightened to call out, they found deer trails, old campfire rings, a trapper’s cabin that hadn’t been used in years, but no children.

By the ninth day, people began to speak in the past tense. The minister prepared himself to deliver a eulogy. Townspeople brought food to the Corbett house the way you do when someone has died. Margaret refused to let them inside. She kept three plates on the table, three cups of water, waiting. Then, on the morning of September 25th, a farm hand named Joseph Ridley was checking his fence line near the northern edge of the woods when he saw them.

Three children standing in a perfect row at the edge of the clearing, still silent, facing the town. He called out to them. They didn’t respond. He ran closer, shouting their names, waving his arms. They didn’t blink, didn’t move, just stood there, staring past him, their hands at their sides, their feet bare and caked with dark soil.

Joseph sprinted back to town, breathless and wide-eyed. Within the hour, Margaret and Samuel and Nathaniel’s father, Clayton Puit, were running through the fields toward the woods. When they reached the clearing, the children were still standing in the same spot, exactly as Joseph had described. Margaret fell to her knees and sobbed.

Samuel tried to embrace his son, but Thomas stepped backward, just out of reach. Clayton picked up Nathaniel and held him tight, but the boy’s body was stiff, unresponsive, like holding a wooden doll. The children said nothing. Their eyes were open, but they weren’t looking at their parents. They were looking through them, past them, at something no one else could see.

They brought the children back to town in a wagon. People lined the streets, silent, watching as the three were carried into the Corbett home. Dr. Ames was called. He examined them for over an hour. No injuries, no fever, no sign of starvation or dehydration. Their pulses were steady. Their lungs clear. Physically, they were fine.

But they wouldn’t speak, wouldn’t eat, wouldn’t sleep. They just sat in the parlor, side by side on the sofa, staring at the wall. For two full days they remained like that, motionless, silent, alive but not living. And then on the third night, Eliza opened her mouth and all three of them began to speak. It wasn’t how children speak.

That’s what Margaret would tell her sister later in a letter that still exists in the Kansas Historical Society archives, though it’s kept in a restricted file. She said it was like listening to three voices coming from one mouth. Calm, flat, without emotion, without breath between the words. They spoke in unison.

Perfect synchronicity. Eliza’s lips moved, but so did Thomas’s. So did Nathaniel’s. The same words at the same moment in the same tone. “We went to the place beneath the hollow oak. The ground was soft. We dug with our hands. There was a door. It opened. We went down.” Margaret asked, “Where? Where did you go? What door?” The children didn’t look at her.

Their eyes remained fixed on the wall. “The stairs go down a long time. It smells like copper, like old rain. There are symbols on the walls. We touched them. They were warm. At the bottom, there is a room. The room is older than the town, older than the trees. Someone was waiting.” Samuel grabbed Thomas by the shoulders and shook him.

“Who?” He shouted. “Who was waiting?” The children blinked slowly, all three at the same time. “It didn’t have a name. It said it had been waiting a long time. It said it needed to see through new eyes. It asked us if we would carry it. We said yes. We didn’t know we were saying yes, but we said it.”

Dr. Ames, who had been standing in the doorway, stepped forward. He was a rational man, a man of science. He asked them what they meant by “carry it.” Was it a person, an animal, a thing? The children turned their heads in unison to look at him. It was the first time they had acknowledged anyone in the room. “It lives in the space behind thought.”

“It doesn’t have a body. It doesn’t need one. It wears us now. It sees what we see. It hears what we hear. And when we sleep, it walks.” Margaret began to weep. Clayton Puit stood and left the room. He would later tell the sheriff that he couldn’t stand to be near his son. That it wasn’t Nathaniel anymore, that something else was looking out from behind his eyes.

Samuel asked the only question that mattered. “How do we get it out?” The children smiled. All three of them, a slow, identical smile that didn’t reach their eyes. “You don’t.” Then they stopped speaking. They stood up, walked to the bedroom they’d been given, lay down in a row on the floor, and closed their eyes. They didn’t move again until morning.

Dr. Ames had no explanation. The minister, Reverend Callaway, was summoned the next day. He prayed over the children. He read scripture. He placed his hand on Eliza’s forehead and asked in the name of Christ for whatever had taken hold of her to release her. Eliza opened her eyes and looked directly at him. “We were never taken,” she said alone this time, her voice soft and clear. “We were invited.”

Reverend Callaway left the house and never returned. A week later, he resigned from his position and moved to Missouri. He refused to speak about the Winfield children for the rest of his life, but the children did speak. Over the following weeks, they gave instructions. Rules, they called them. Rules the town had to follow.

And terrified, confused, and desperate to believe their children could still be saved, the parents obeyed. The rules were simple. Too simple. That’s what made them so unsettling. They weren’t demands for sacrifice or worship or blood. They were small, specific, mundane instructions that made no sense until people started breaking them.

Rule one: No one in Winfield was to light a fire after sunset on Tuesdays.

Rule two: Every household must leave one window open at night, no matter the season.

Rule three: No mirrors were to be placed facing a doorway.

Rule four: If you heard your name called from the woods, you were not to answer. You were not to look. You were to go inside, close the door, and wait until morning.

Rule five: The children were to be allowed to walk wherever they wished, whenever they wished. No one was to follow them. No one was to ask where they had been.

The parents tried to rationalize it. Margaret told herself that the children were traumatized, confused, that they’d been lost in the woods and had invented some shared delusion to cope with the terror. Samuel convinced himself that with time, routine, and care, his son would return to normal. Clayton Puit said nothing. He began drinking heavily and slept in the barn.

For the first two weeks, people followed the rules. It felt foolish, superstitious, but harmless. No fires on Tuesday nights. Windows cracked open. Mirrors turned to face the walls. It was easier to comply than to argue. And then on October 9th, 1879, a man named Benjamin Tate broke rule one.

Benjamin was a blacksmith, a practical man, a man who didn’t believe in ghosts or devils or children speaking in riddles. On a Tuesday evening, he lit his forge to finish a repair job that couldn’t wait. He told his wife, Anne, that he didn’t care what those children had said. He had work to do. At 10:00 that night, Anne heard him screaming.

She ran to the forge and found him on the ground convulsing, his hands clawing at his face. His eyes were open, but he wasn’t seeing her. He was seeing something else, something that made him scream until his voice gave out. By the time Dr. Ames arrived, Benjamin had gone silent. He was alive, breathing. But he never spoke again. He would sit in a chair by the window, staring, unblinking until he died 3 months later.

The town was shaken, but some still refused to believe. They said Benjamin had suffered a stroke, a fit, some kind of sudden illness, coincidence, tragic, but explainable. Then on October 16th, a woman named Judith Marsh closed all her windows and locked her doors. She told her husband she didn’t care what the children said. She wasn’t going to let the cold night air into her house and risk her daughters catching fever.

That night, Judith woke to the sound of breathing, heavy, wet. Right next to her ear. She lit a candle. There was no one there. But the breathing didn’t stop. It followed her from room to room. It grew louder, closer. Her husband couldn’t hear it. Her daughters couldn’t hear it. Only Judith. For 3 days, it didn’t stop. She couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat. On the fourth day, she walked into Miller’s Creek and drowned herself.

After that, no one broke the rules. The children continued their strange routines. Every evening, just before dusk, they would walk to the edge of town, stand facing the woods, and remain there for exactly 1 hour. Then they would return silent and go to bed. Sometimes people saw them in places they shouldn’t have been able to reach, on rooftops, in locked sheds, standing in the middle of fields miles from town. No one asked how they got there. No one dared.

And at night, people began to hear them. Not their voices, their footsteps, soft, deliberate, moving through the streets long after the children had gone to bed. Walking in perfect unison. Three sets of feet, always together, always searching.

By November, Winfield was no longer a town. It was a place held together by fear and whispered prayers. People stopped visiting one another. Families kept to themselves. The general store saw fewer customers each week. The schoolhouse closed. Parents wouldn’t send their children anywhere near Eliza, Thomas, and Nathaniel, who still attended as if nothing had changed. Sitting in the back row, silent, their eyes tracking movement like predators watching prey.

The teacher, a young woman named Catherine Wells, resigned after one week. She told the school board that the children didn’t blink, that when she turned her back to write on the chalkboard, she could feel them staring. That one morning, she found the words “soon” carved into her desk. When she asked who had done it, all three children raised their hands. They smiled.

Margaret Corbett stopped leaving her house. She would sit by the window, watching Eliza come and go, and she would weep. Neighbors reported hearing her at night, pleading with her daughter, begging whatever was inside her to let her go. Eliza never responded. She would simply stand in the doorway of her mother’s room, head tilted, watching, waiting.

Samuel tried to run. On November 12th, he packed a bag, hitched his horse, and rode south toward Wichita in the middle of the night. He made it 11 miles. The next morning, a farmer found him on the side of the road, sitting in the dirt, staring at his hands. His horse was gone. His bag was gone. When the farmer asked what happened, Samuel whispered, “They followed me. I can’t leave. None of us can.”

He returned to Winfield that afternoon. He never tried to leave again. Clayton Puit lasted longer. He convinced himself that his son was still in there, that Nathaniel could be reached, could be saved. He spent hours trying to talk to him, asking him questions about his favorite things, his memories, anything that might spark recognition.

Nathaniel would sit and listen, patient, polite, and then he would say in that calm, empty voice, “I remember being him, but I am not him anymore.” On November 23rd, Clayton walked into the woods. A search party found his body 3 days later, hanging from the hollow oak the children had described. There was no note, but carved into the bark beneath him were the words, “It showed me.”

The town began to fracture. Some families packed up and left in the dead of night, abandoning their homes, their land, everything. Others stayed, paralyzed by fear or by some unspoken belief that running would only make it worse. The ones who left never spoke of Winfield again. And the ones who stayed, well, most of them didn’t last much longer.

By December, people started seeing things. Shapes in the woods, faces in windows that shouldn’t have faces. Shadows that moved against the light. A farmer named Ethan Low swore he saw his dead brother standing in his field. A woman named Sarah Kinsley found her own reflection missing from her mirror one morning. It came back 3 days later, but it didn’t move when she did.

And through it all, the children walked. They walked through town like they owned it, like they were waiting for something. And every night, people could hear them. Those footsteps, slow, steady, synchronized, moving through the streets, stopping at doors, listening.

On December 14th, Eliza knocked on a door for the first time. It was the home of a man named Victor Hayes, who had two weeks earlier refused to follow rule four. He had heard his name called from the woods and he had answered. Victor opened the door. Eliza stood on his porch alone, her head tilted, her eyes reflecting the lamplight like an animal’s. “It’s time,” she said.

Victor was found the next morning in his bed, eyes open, no wounds, no signs of struggle, but his face was locked in an expression of such profound terror that the undertaker refused to prepare the body. He was buried with a sheet over his face.

By Christmas 1879, 12 people were dead, and the children were still walking. January of 1880 was the coldest winter Kansas had seen in 20 years. Snow piled high against doorways. The wind cut through the plains like a blade. But the cold wasn’t what drove people out of Winfield. It was the realization that the town was dying. Not slowly, not naturally, but deliberately, methodically, like something was feeding on it.

Margaret Corbett was found on January 7th. She had locked herself in her bedroom, nailed the door shut from the inside, and pushed her wardrobe against it. It didn’t matter. When her sister broke through 3 days later, Margaret was sitting upright in her bed, her hands folded in her lap, her eyes open and dry. She had stopped breathing sometime in the night. On the wall above her bed, written in what looked like soot, were the words: “She finally saw.”

Eliza was standing in the hallway when they carried the body out. She didn’t cry, didn’t speak. She just watched, her face blank as her mother was taken away. Then she turned and walked back to her room. Neighbors reported hearing her humming that night, a song no one recognized, a melody that made their teeth ache.

Samuel lasted until February. He stopped eating, stopped speaking. He would sit at his kitchen table staring at Thomas who would sit across from him, staring back. They would stay like that for hours, days even. When Dr. Ames checked on him, Samuel grabbed his wrist and whispered, “It’s not just in him, it’s in me now, too. I can feel it learning how to move my hands.”

Samuel died on February 19th. The official record says heart failure, but the people who found him said his eyes were open and he was smiling. By March, more than half the town had left. Entire families gone in the night. Homes abandoned with food still on the tables, clothes still in the drawers, doors left wide open. Those who remained were the ones who couldn’t leave, either because they had nowhere to go or because they believed somewhere deep down that leaving wouldn’t save them.

The children were never alone. Even after their parents died, they stayed in the Corbett house. People brought them food, left it on the porch, and hurried away. The food was always gone by morning, but no one ever saw them eat. No one saw them sleep. They simply existed, waiting, and the woods grew darker, thicker. People swore the treeline was closer than it had been. That the hollow oak, the one Clayton had died beneath, was larger now, its branches twisted into shapes that looked almost like hands, almost like faces.

In April, a group of men from a neighboring town arrived, led by a federal marshal named William Hackett. They had heard rumors, impossible rumors, stories of children who couldn’t die, of a town cursed, of people vanishing or losing their minds. Marshal Hackett didn’t believe in curses. He believed in law, in order, in rational explanations.

He demanded to speak with the children. He was brought to the Corbett house. Eliza, Thomas, and Nathaniel were sitting in the parlor, side by side, exactly as they had been the day they returned. Marshal Hackett asked them what had happened in the woods, where they had gone, what they had found. The children looked at him. All three at the same time. “You want to know?” Eliza asked. “Yes,” Hackett said. “Then go and see.”

The marshal and two of his men went to the woods that afternoon. They found the hollow oak. They found the soft ground beneath it. And they found the door. Just as the children had described, a wooden hatch, old and rotted, covered in symbols that none of them recognized. Marshal Hackett ordered his men to open it. They refused. He opened it himself.

The stairs went down, down further than any staircase should go, down into a darkness so complete it seemed to swallow the light from their lanterns. The air smelled like copper, like old rain, just as the children had said. Marshal Hackett descended alone. He was gone for 11 minutes. When he came back up, his face was gray. His hands were shaking. He didn’t speak. He walked directly to his horse, mounted it, and rode out of Winfield without a word. His men followed. They filed no report.

Marshal Hackett resigned from his position 3 weeks later. He moved to Oregon and never returned to Kansas. In a letter to his brother years later, he wrote only this: “There are doors that should never be opened. And there are things behind those doors that have been waiting a very, very long time.”

By 1881, Winfield was a ghost town. Fewer than 30 people remained. The children were still there. By 1885, Winfield, Kansas, no longer appeared on most maps. The post office closed. The rail line rerouted. The few families who remained finally left quietly without explanation. The town was abandoned, empty, silent, but not forgotten.

The children, Eliza Corbett, Thomas Corbett, and Nathaniel Puit, were last seen in the spring of 1884. A passing traveler reported seeing three children standing in the middle of the town square, holding hands, facing the woods. When he returned an hour later, they were gone. No footprints, no trace, just an empty street and the wind moving through abandoned buildings.

Some say they went back into the woods, back down through the door beneath the hollow oak. Others say they’re still there, walking the empty streets at night, waiting for someone to come back, waiting to be seen. In 1897, a fire swept through what was left of Winfield. No one knows how it started. By the time it burned out, nearly every structure was gone. The Corbett house, the church, the schoolhouse, all of it reduced to ash and foundation stones.

The only thing that survived was the hollow oak. It still stands today, gnarled and massive in what is now an empty field off County Road 12. People avoid it. Locals won’t go near it, especially at night. Hunters who’ve wandered too close report hearing voices, children’s voices, singing, laughing, calling out names. And if you stay too long, they say you start to feel it. That pull, that invitation. The same one Eliza and Thomas and Nathaniel must have felt all those years ago.

In 1972, a team of researchers from the University of Kansas attempted to investigate the site. They brought ground penetrating radar, cameras, recording equipment. They found the remains of the town. They found the hollow oak and beneath it, they found something else, an anomaly, a void in the ground that their equipment couldn’t penetrate, a space that registered as impossibly deep. They dug down 6 feet and found the remnants of a wooden hatch rotted and collapsed.

They stopped digging. The lead researcher, Dr. Alan Marsh, wrote in his notes, “There is a psychological weight to this place that I cannot explain. We all felt it, a pressure, a presence. We decided not to continue.” The site was marked, cataloged, and quietly forgotten. The university sealed the records. Dr. Marsh never published his findings.

When a journalist asked him about it years later, he said only: “Some places are meant to stay buried.” But the story didn’t stay buried. It couldn’t. Over the years, pieces of it surfaced. Letters, diary entries, census records that showed a town of over 200 people in 1878, and fewer than 30 by 1882. Death certificates with causes listed as unknown or unexplained. A minister’s journal that described children who spoke in unison and gave rules that no one dared to break.

And there are people even now who claim to be descended from the families who fled Winfield. They don’t talk about it openly, but in private, in whispers, they’ll tell you that their great-great-grandparents left Kansas in the middle of the night and never looked back. That they were told never to return, never to speak the name Winfield aloud, never to go looking for answers, because some answers, they say, come with a price.

In 2009, a hiker reported finding three sets of children’s footprints near the old Winfield site, small, barefoot, leading from the tree line to the center of the empty field where they simply stopped. No tracks leading away, just three sets of prints side by side as if the children had been standing there watching, waiting. The local sheriff dismissed it as a prank, but the hiker never went back, and neither did anyone else.

There are no memorials in Winfield, no historical markers, no plaques. The town has been erased purposefully and completely from the official record. If you search for it in the Kansas State Archives, you’ll find almost nothing. A few scattered references are mentioned in a census report, a single newspaper article from 1879 about three missing children, and then silence.

But silence doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. It just means someone decided it was better not to talk about it. The Winfield children were found in 1879. What they explained didn’t sound human, and what they brought back with them, whatever walked up those stairs behind them, may still be there waiting, watching, listening for someone to break the rules, for someone to answer when their name is called from the woods.

So, if you ever find yourself driving through southeastern Kansas and you see an old twisted oak tree standing alone in an empty field, keep driving. Don’t stop. Don’t look too long. And whatever you do, if you hear children laughing in the distance, don’t go looking for them because some invitations should never be accepted and some doors should never be opened.

News

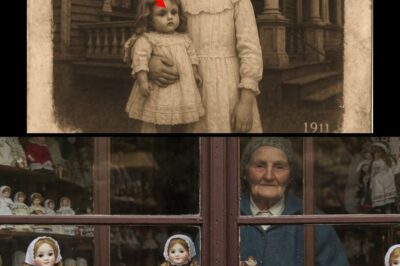

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

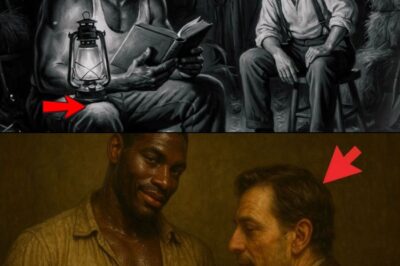

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load