The Stepmother and Stepson Case (1913): The creepy mystery of the missing eye

Imagine an 11-year-old child sitting motionless on a bed, one eye missing, the other staring wide open, unblinking. When the doctor removed the blood-soaked bandages, he trembled and dropped his medical forceps. Because he did not find the ragged tear of a farming accident as the family had claimed, but rather an empty eye socket, surgically removed with perfect precision. A detail so clean it was terrifying.

That person not only shook the Ozark mountains in 1913 but also forced me to shudder and admit a brutal truth. Sometimes, the devil does not hide in the shadows; it holds a scalpel, smiles gently, and calls itself “Mother.” Welcome to today’s journey Into the Darkness.

Before I tell you what happened in that valley of death, I want you to imagine a cold morning. A cold that doesn’t just come from the weather, but seeps into your very marrow. It was October 17, 1913, a morning when thick fog blanketed the Ozark mountains in southern Missouri. In these parts, the fog isn’t romantic like in poetry.

It is thick, milky white, and clings to everything as if trying to hide humanity’s dirtiest secrets. This Ozark region, with its labyrinthine caves and ancient oak forests, has long been a refuge for those running from the law, from society, or from their own pasts.

The Thorn family at Thorn Hollow Farm was no exception. I am Silas Crow, the sheriff of this impoverished county. That year I was 52, an age where one starts seeking peace rather than chases. That morning, I was sitting at headquarters, holding a cup of hot coffee that offered no warmth, when I received a telegram from Caleb.

Caleb is a delivery boy as honest as the day is long; he’s never told a lie in his life. So when I read the brief lines he sent—”Accident at Thorn Hollow, the boy is badly hurt, something isn’t right. Come immediately”—a chill ran down my spine. You know, in this godforsaken place, agricultural accidents happen like clockwork.

People break legs, get arms cut by machines; it’s heartbreaking, but normal. But Caleb’s phrase “something isn’t right”… it was like a needle pricking my intuition. Caleb isn’t one to embellish. He had seen something that made a calloused man panic. And I knew I had to go immediately.

Thorn Hollow lies about seven miles of forest road from town. A winding red dirt road like a scar slicing through the dense woods. When my car stopped in front of the farm gate, the first thing that struck me was the silence. A deadly silence. No dogs barking, no livestock sounds, just the wind whistling through the cracks in the doors.

The two-story wooden house of the Thorns stood there, cold and gloomy. Its owner, Elias Thorn, was a pitiful widower. After his first wife died of lung disease, he collapsed completely, living a reclusive life raising his son, Samuel. But then, half a year ago, he unexpectedly remarried a woman named Lydia Vane, a seamstress from the city of Springfield.

Lydia’s appearance in this remote place caused a stir because she was too different, too clean compared to the dust of the farm. And today, that very cleanliness was what haunted me the most. Stepping inside, the first scene that made me freeze wasn’t blood, but the bizarre contrast between husband and wife.

Elias Thorn slumped at the kitchen table, his face drained of blood, hands trembling as he clutched a cup of coffee that had gone cold long ago. He looked ten years older overnight. His deep-set eyes held sheer terror, yet he dared not speak a word. In contrast, Lydia Vane stood by the fireplace, back straight, her black hair pulled up in a neat bun, not a single strand out of place.

She wore a dark dress that was spotless, not a speck of dust or a drop of blood on it. Think about it: could a mother, even a stepmother, seeing her child in a horrific accident, maintain such a terrifyingly calm demeanor? When she turned to look at me, that gaze… it held no worry, no panic, but was sharp and alert like a scalpel blade.

She greeted me with a voice that was soothing but emotionless, saying that Samuel had fallen onto a rake in the barn. I rushed upstairs to where Samuel lay, the small room still adorned with his late mother’s rosary beads. Now, it reeked of antiseptic—a scent too professional for a farming household.

Dr. Arthur Penaligon, the best physician in the region, was packing his bag with a look of helplessness and confusion. He pulled me into the corner of the hallway, whispering in a trembling voice that, in all his years of medicine, I had never heard before. “Silas, I did my best, but this wound is strange.” I asked, strange how? He swallowed hard and leaned close to my ear, “The boy’s eye socket is empty, but there are no signs of tearing or crushing like a normal accident.”

“It… it’s too clean, Silas. It looks like the eye was removed precisely with a sharp instrument, not by falling onto a rusty rake.” I looked at the poor child lying motionless on the bed. Samuel was only 11. His face was bandaged on one side, and the remaining eye… Oh God, the boy’s remaining left eye was wide open.

The pupil was fully dilated, staring blankly at the ceiling, seeing nothing. He didn’t cry, didn’t moan, just lay there like a broken doll. When I tried to talk to him, the boy remained silent. And when I mentioned Lydia, I saw his tiny hand spasm, clutching the bedsheet until his knuckles turned white. That was not the reaction of a child cared for by a mother; that was the reaction of prey hearing the name of the hunter.

Downstairs, I confronted Lydia and asked her about the accident. She recounted it fluently. Every detail matched perfectly—too perfectly. “I heard him scream,” she said, “I ran out and saw blood.” But when I asked about the clothes she was wearing at the time, she just smiled, a smile that didn’t reach her eyes.

“I changed already, Sheriff. Blood is filthy; guests shouldn’t see it.” The way she spoke of “filthy blood” was like she was talking about mud splattered on a dress, not the blood of the son lying paralyzed upstairs. And Elias, the biological father, sat there silent as a soulless corpse.

Every time he started to open his mouth, he would glance at Lydia, and with just a slight raise of her eyebrow, he would bow his head again. At that moment, I realized something terrible. In this house, Elias was no longer the master. He was a prisoner. And Samuel… Samuel was something else, a sacrificial object for a dark purpose I couldn’t yet name.

I left Thorn Hollow with a feeling of helplessness weighing on my chest. No concrete evidence, no weapon, just the consistent testimony of the couple about an accident. But the cold feeling from Lydia’s gaze and the emptiness in Samuel’s eye socket haunted me.

Why could a woman be so calm in the face of a child’s pain? Why was a father so afraid of his wife that he dared not protect his son? And most importantly, Samuel’s eye—where did it go? Those questions swirled in my head all the way back, signaling a series of tragedies that, looking back later, I wish I had acted more decisively on that foggy morning.

Let me tell you, the coldness covering Thorn Hollow that day didn’t appear naturally. It didn’t happen overnight; it had seeped into every grain of wood, every brick of that house starting six months prior. Starting from the day that woman stepped off the carriage from Springfield.

Before Lydia Vane appeared, the Thorn family was part of the flesh and blood of this land. I still remember the image of Elias from the old days. He wasn’t the trembling, cowardly man I just met in the kitchen. Elias used to be a robust farmer.

His hearty laughter could echo through the valley every harvest season. And beside him was always Mary, his gentle first wife with the most skillful hands in the region. Mary died in 1910 of lung disease during a harsh winter; her death left a vast void in the house. And more importantly, it gouged a large hole in Elias’s soul.

He collapsed, struggling between loneliness and the burden of raising a small son. And as you know, predators can always smell the scent of vulnerability from a great distance. In April 1913, when wildflowers began to bloom on the hillsides, Elias unexpectedly brought Lydia Vane home. There was no grand wedding, no celebration with neighbors, just a cold marriage certificate with two signatures of strangers from the town as witnesses.

Lydia introduced herself as a seamstress from the city, but honestly, the first time I met her at the general store, I felt uneasy. Lydia Vane was beautiful, but it was an artificial beauty, out of place amidst the harsh sun and wind of the Ozarks.

Her skin was pale as if it had never touched sunlight, and those eyes—those deep black eyes—always looked at others with a scrutiny, an assessment, as if she were pricing an item rather than greeting a human being. She didn’t join the women’s sewing circle, didn’t go to church, and never smiled back at social greetings.

She walked among the mud-stained farmers with her chin held high, as if wearing an invisible crown, separating herself from the mediocrity around her. But what worried me and neighbor Clara Halloway the most wasn’t Lydia’s arrogance, but how she cared for Samuel.

Previously, Samuel was a wild child of the mountains in the truest sense. He ran everywhere, knees always scraped, mouth always chattering about bird nests or creek fish he caught. But after just a few weeks living with his stepmother, Samuel began to change. He no longer ran to the gate to greet guests.

He was always inside or sitting silently on the porch, clothes weirdly clean, hair combed smooth, hands always holding a book—books Lydia brought back. High-level academic books that an 11-year-old farm boy could never understand. I remember once stopping by the farm to deliver mail. I saw Samuel sitting on the old swing, but he wasn’t swinging. He just sat there. Motionless.

When I called his name, the boy turned slowly like a rusty machine. His gaze at that time… I didn’t understand it then, but thinking back now, I shudder. It was the gaze of someone trying to look through reality, or rather, the gaze of someone being looked for. When I asked, “How are you lately, Sam?” the boy didn’t answer immediately. He glanced toward the second-floor window.

Where the red velvet curtain moved slightly, only then did he reply in a flat, emotionless voice: “Mother Lydia says I am progressing very well; I don’t need to go out to play anymore.” What did Lydia do? She didn’t beat the boy, didn’t starve him, at least not in a way we could see with the naked eye. She did something far more cruel. She severed every connection the boy had with the world.

She pulled him out of the village school citing weak health and homeschooled him. She built an invisible wall around Samuel’s immature mind, turning him into her private property. Gradually, people no longer saw Elias with his son. Instead, whenever the Thorn carriage went down to town, people only saw Lydia holding the reins, and behind the tiny glass window of the carriage, Samuel’s face appeared—blurred, pale, staring at other children playing with a silent hunger mixed with fear.

My friends, the silence of a child is far scarier than its crying. Crying means it still knows pain, still wants to resist. Samuel’s silence then was a sign of acceptance. The boy had accepted that his body, his thoughts, no longer belonged to him.

And Elias, that once-strong man, now shrank like a shadow. He drank more, not to get drunk, but to forget. Once, he stopped by the tavern, intending to say something to me. His lips moved, his trembling hand placed on my shoulder, but then he froze, eyes darting around as if afraid someone was eavesdropping.

Finally, he just sighed, bought another pack of cigarettes, and trudged home. At that time, I asked myself, what is he afraid of? Afraid of a weak woman? Or was he afraid of something darker hiding behind his wife’s decorous exterior? The change happened slowly, smoothly like a dose of anesthetic, making us outsiders feel only a slight unease but without enough evidence to intervene. We just tutted: “Every family has its own issues.”

But if only… if only I had been more sensitive. If only I had realized that Samuel’s excessive cleanliness, Elias’s silence, and Lydia’s arrogant gaze were the first dominoes falling, leading to that bloody morning of October 17th. A rake tearing an eye? No.

Now, as I piece together the past, I am certain it was never an accident. It was the next step in a plan calculated meticulously from the day Lydia stepped off the train at Springfield station with a suitcase full of tools not meant for sewing. That night, after leaving Thorn Hollow, I couldn’t sleep a wink.

The image of Samuel with the empty eye socket kept hovering in my mind like a ghost. But what really kept me tossing and turning wasn’t the gruesomeness of the wound, but the suspicious silence of Dr. Arthur Penaligon at the scene. I’ve known Arthur for over 30 years. He is a tough man, used to sawing off soldiers’ legs in the war without his hand shaking. Yet, this morning, he trembled.

The next morning, I went to Arthur’s clinic. He was sitting in the dark. Even though the sun was high outside, on his table was a bottle of strong liquor, half empty. When he saw me, he didn’t greet me, just pushed a handwritten report toward me. “Read it, Silas,” he said, his voice hoarse, then told me: “Is there any hay rake in this world that knows how to perform surgery?” I picked up the paper.

Arthur’s shaky handwriting described a truth my reason didn’t want to believe. According to the family, Samuel fell face-first onto farm tools. If so, the wound should be jagged, flesh torn, orbital bone cracked or shattered from heavy impact. But no, Arthur pointed at the paper, his finger tapping hard on the wooden table. “The wound is too clean, Silas.”

“No jagged tears, no metal fragments or rust. The muscles and optic nerve… they were cut. Do you hear me? Cut. Smoothly, decisively.” I felt my spine freeze. Arthur looked straight into my eyes, the look of a man afraid of his own knowledge.

“To do that on a struggling child, the person holding the knife must have extremely profound anatomical knowledge and nerves of steel. It wasn’t first aid, Silas. It was a harvest.” Arthur’s word “harvest” haunted me all the way back to Thorn Hollow that very afternoon. I needed to talk to Samuel. And this time, I needed the real answer, not spoon-fed lines.

When I arrived, Lydia was in the garden airing out black fabrics—thick, heavy cloth that didn’t suit the autumn weather at all. Elias was nowhere to be seen. I slipped into the house, went straight to Samuel’s room. The boy was still sitting there on the bed, in the exact same posture as yesterday, as if he hadn’t moved a single millimeter. “Samuel,” I called softly, pulling a chair close.

“It’s Uncle Silas. I want to know the truth. Who did this to you?” The boy turned his face toward me, and this was when I noticed the horrifying detail I had missed in yesterday’s panic. His remaining left eye… the pupil was dilated abnormally large, taking up almost the entire iris, pitch black and deep as a dry well.

In daylight conditions like this, the pupil should constrict. But Samuel’s eye didn’t. It stared wide open but looked glazed, as if he were looking into some indefinite void rather than at me. “I fell, sir,” Samuel answered. The boy’s voice was monotonous—not high, not low, not trembling.

It sounded like a parrot mimicking human speech or metal grinding together rather than the voice of an 11-year-old child. I grabbed the boy’s shoulders, trying to shake him. “Sam, listen to me, I know a rake can’t do that. Did she do it? Was it Lydia?” The moment I mentioned that name, Samuel’s body went rigid.

He didn’t shrink back in fear like regular abused children. He stiffened like a machine with jammed gears, his mouth moved, and a distorted, forced smile appeared on his pale face. “Mother Lydia loves me, Mother takes care of me, Mother washes my wound with salt water and leaves.”

“Mother makes the pain go away.” Salt water and leaves? I repeated, feeling goosebumps. Just then, a cold voice rang out from the door. “Boiled salt water to sterilize and poppy leaves to sedate. Sheriff, those are basic knowledges any woman should know.” I started and turned around. Lydia Vane stood leaning against the doorframe, holding a tray of medicine.

She walked into the room, her footsteps silent on the old wooden floor. She set the tray down, looking at me with arrogant defiance. “You seem to know more about medicine than a regular seamstress,” I said, trying to keep my voice calm, though my hand unconsciously rested on my holster. Lydia smiled, a smile that only quirked the corner of her mouth. “My father was an assistant to a military doctor.”

“He taught me that precision is the greatest mercy. A clean cut hurts less than a jagged scratch. Doesn’t it, Sheriff?” That sentence… it was like an arrogant confession wrapped in a philosophical shell. She didn’t deny the precision of the wound. She was bragging about it. She was telling me she held the knife, cut into her stepson’s flesh with mercy and sweetness.

I looked at Samuel; the boy was looking at Lydia with his remaining eye. A look both adoring and terrified, like a dog looking at a master holding a whip. And Lydia, she walked to the bed, placing a long, cold white hand on the boy’s forehead. Immediately, Samuel closed his eyes, exhaled, his body relaxing completely as if a switch had been turned off.

“The boy needs rest,” Lydia said, not looking at me, her hand still stroking the bandage on Samuel’s face in a terrifyingly affectionate way. “And you should leave, Sheriff. There is no crime here, only healing in a way you ordinary people cannot understand.” I walked out of that room, my heart heavy as lead.

I knew Arthur was right; this was no accident. But it wasn’t exactly domestic abuse in the traditional sense either. An abuser usually acts out of anger, out of a loss of control. But Lydia Vane… she was too calm, too meticulous. She used medical knowledge, sedatives, and psychological manipulation to turn a lively child into an obedient test subject.

And the question “Why?” kept screaming in my head. Why the eye? Why did she need such precision? I didn’t know then that to Lydia, Samuel wasn’t a human. The boy was a jar, a vessel. And you don’t smash a jar to get what’s inside. You have to open it carefully.

Today she opened one lid, and I shuddered to think what she would do when that lid was no longer enough to satisfy her thirst. Night was falling on Thorn Hollow, and I felt like I was leaving Samuel in the belly of a monster. A monster that knew how to use a scalpel and wore a black silk dress.

Then winter struck, fast and brutal like a death sentence for this mountain region. That year, snow fell so thick that trails disappeared overnight, completely isolating the farms from the outside world. But for Thorn Hollow, I felt that snowstorm wasn’t just a weather phenomenon; it was like a white curtain drawn by nature to hide the sins occurring inside that wooden house.

Throughout November, no one saw a sign of the Thorn family. No carriage went to town for supplies, no kitchen smoke rose during usual cooking hours. Their silence drowned in the muteness of winter, freezing my and Dr. Arthur’s worries, burying them under meters of snow. We were cowardly. I admit that.

We used the excuse of difficult roads to justify not going back to check. It wasn’t until early December, when Christmas preparations began to kindle in town, that someone brave enough—or curious enough—broke the stalemate. That was Clara Halloway. Clara was a widow living on the next farm, about two miles through the woods from the Thorns. She was a typical Ozark woman.

Tough, forthright, and trusting in the Lord as much as she trusted the hunting rifle on her wall. She never believed in Samuel’s so-called accident. So, on a rare sunny morning in December, Clara took a basket of jam and hot bread, deciding to wade through the snow to visit her neighbors. She told me she went to give Christmas gifts.

But I knew Clara went to find the answer that I—a sheriff—had dared not seek. And what Clara recounted to me afterward, in my office warm with the scent of pine wood but unable to dispel the chill in her voice, haunted me until the end of my life.

Clara said when she arrived, the Thorn Hollow farm gate was shut tight, the latch rusty, as if untouched for a long time. When she knocked, it took a long time to hear any movement. The door opened, and the first thing that greeted her wasn’t the warmth of a fireplace, but a strange smell rushing straight into her nose. It wasn’t the musty smell of an old house, nor the smell of food.

“It smelled sharp of salt, Silas,” Clara said, her eyes wide with fear. “Salty salt mixed with the smell of rubbing alcohol. So strong I felt like I was walking into a laboratory, not a farmer’s living room.” Lydia Vane was the one who opened the door. She wore a black dress reaching her heels, high collar buttoned tight, face pale without makeup, but lips red as if she had just drunk blood.

She didn’t invite Clara in but stood blocking the threshold like a guard dog. But Clara, with her stubborn nature, squeezed past her, using the excuse that it was too cold outside and she needed to warm up a bit. The scene inside the house made Clara’s heart constrict. All curtains were drawn tight, making the room pitch black even though it was daytime.

Samuel was sitting on a hard wooden chair placed right in the middle of the room, facing the fireplace but sitting with his back to the flames. The boy was visibly emaciated, cheekbones protruding, the old eye bandage turned a dingy gray. But the scariest thing was that he sat perfectly still, hands placed neatly on his lap, not moving, not turning his head at the sound of a stranger.

“Samuel,” Clara called softly. The boy didn’t answer; he didn’t react. Lydia walked over, standing right behind Samuel’s chair. Clara swore to me that the moment Lydia placed her two hands on the boy’s shoulders, Samuel shuddered violently, as if an electric current ran through him. “Samuel is focusing on his studies,” Lydia said, voice smooth but cold as ice.

“He is learning to look inside instead of looking outside, isn’t he, son?” And then Samuel’s small mouth moved. He spoke, but it was a soulless sound, monotonous, devoid of human emotion. “Yes, Mother. I am learning to look into the darkness. Darkness is a friend; light hurts the eyes.”

Clara said she almost dropped the basket of bread. An 11-year-old child doesn’t say words like that. Those were spoon-fed words, brainwashed, stuffed into his head over hundreds of hours of solitary confinement in the dark. Clara tried to step closer, offering the boy a cookie. Samuel glanced at the cookie, then slowly raised his remaining eye to look at Lydia.

He was asking for permission. A starving, skeletal child had to ask for permission with his eyes to eat a cookie. Lydia nodded slightly, a nod almost imperceptible. Only then did Samuel dare reach out to take the cookie, but he didn’t eat it immediately; he clutched it tight in his hand, so tight that crumbs fell onto the floor.

Just then, Elias appeared from the kitchen. If Samuel looked like a puppet, Elias looked like a wandering ghost. His hair and beard had grown long and ragged, clothes disheveled, smelling of stale liquor and sweat. He looked at Clara, and in a brief moment, Clara saw a spark flash in his cloudy eyes—it was a plea for help.

“Elias,” Clara said, “Are you alright? You look…” Elias opened his mouth to say something, his lips trembling, tears about to spill. He took a step toward Clara, hand raised as if wanting to grab hers. But the moment he moved, Lydia, still standing behind Samuel, simply cleared her throat softly. A gentle, polite clearing of the throat.

But its effect on Elias was horrific. He froze instantly, hand dropping limp, back hunching as if someone had just broken his spine. The light in his eyes extinguished, replaced by pure, naked fear. He backed away, retreating into the shadows of the kitchen hallway, muttering nonsense.

“We’re fine, fine. You leave, don’t come back.” Clara recounted that at that moment, she felt a suffocating pressure she couldn’t stand. The air in the house thickened, weighing on her lungs, making it impossible to breathe. She felt as if thousands of invisible eyes were watching her from the dark corners of the room, from the velvet curtains, and from Lydia Vane’s own deep, black eyes.

She hurriedly set the basket on the table and excused herself, practically fleeing the house. But before she could step out the door, she heard Samuel’s voice echoing after her. This time, the boy’s voice wasn’t monotonous anymore; it rang out sharp and bizarre like a prophecy. “Don’t worry, Mrs. Clara, it’s almost done. Mother says it’s almost done. When the snow melts, I will see everything.”

“I will even see what you are thinking.” Clara ran all the way home, locked the door tight, and sat trembling by the fireplace until her husband returned. She came to find me the very next morning. “Silas,” she said, clutching my hand. “You have to do something. That boy, he isn’t Samuel anymore. And Elias… Elias is already dead; he just hasn’t been laid in a grave yet.”

I listened to Clara’s story with a heart cutting in pain. I knew she was right; the stability Lydia built was just a fragile shell covering a brutal destruction taking place inside. Why the smell of salt? Why did Samuel talk about looking into the darkness and “what is almost done”? Those questions spiraled in my head, but the snowstorm outside screamed as if to stop me.

Or perhaps to give Lydia more time to complete her monstrous work. I looked out the window; the snow was still falling white, beautiful but cruel. I didn’t know that while I sat there hesitating, at Thorn Hollow, Elias was living the final days of his life in a cold hell that his own cowardice had helped create.

And Samuel, that poor child, was being drowned deeper into the quagmire of a mad sorcery. Where the only light he saw was the reflection from his stepmother’s scalpel. That winter was long and endless, and its silence was the prelude to a bloody spring to come.

Spring 1914 arrived in the Ozarks not with birdsong or green buds, but with muddiness. The melting snow revealed layers of black, slushy mud, slippery as if wanting to swallow everything. And along with the mud, the horrifying secrets of Thorn Hollow began to rise from the earth. It was a day in mid-April when the persistent drizzle had just stopped; Clara Halloway came to find me again.

This time she didn’t carry vague worry like the previous winter, but sheer panic. She said her intuition told her to return to that farm, that last night she dreamt of Samuel standing at the edge of the forest, one hand covering his eye, the other waving at her in despair. When Clara arrived, she found Elias in the yard. He was chopping wood, but not with the rhythm of a worker, but with madness, hacking the axe into the log as if trying to kill an invisible enemy.

Seeing Clara, Elias startled and dropped the axe. His face was gaunt to the skull, dark circles under his eyes darting around like a hunted animal. “They left!” Elias screamed before Clara could ask. “Lydia took the boy to Springfield city. They went to see a glass eye specialist. Yes, a glass eye, it will be beautiful, it will look just like real.”

He spoke rapidly, repeating himself, spittle flying from his lips. But Clara, with the sharpness of an experienced woman, immediately recognized the lie in those words. “When did they leave?” she asked. Elias froze. First he said they left this morning, then later said last week. And when Clara deliberately stepped closer, he backed away, using his foot to rub over a patch of freshly turned earth in the corner of the garden, sweating profusely even though the air was cool.

“Don’t go in the house!” He shrieked when Clara moved toward the porch. “Lydia doesn’t like strangers entering when she’s away. She… she will know. She sees everything.” The way Elias said “she sees everything” didn’t imply respect, but terror. As if Lydia wasn’t just his wife but a supernatural force monitoring him even when absent. Clara ran back to report to me, and this time I didn’t hesitate.

I gathered two deputy sheriffs, armed with guns and a search warrant, and rushed straight to Thorn Hollow in the late afternoon. When we arrived, Elias had vanished. The house doors were wide open, silent and empty. But what chilled my spine wasn’t the emptiness, but the absurd cleanliness of it.

The floor was scrubbed shiny, not a speck of dust. The stove was cold, ashes cleaned out completely. No dirty clothes, no unwashed dishes. It was like a model home, or rather, like a crime scene meticulously erased with bleach and boiling water.

The smell of antiseptic still lingered, overpowering the musty scent of rotting wood. I walked into Samuel’s room. It was bare; clothes, books, all gone. Only the iron bed remained, bleak with a bare mattress. And there, right on the wooden headboard, I found something that tightened my heart. Carvings.

Deep, crooked carvings made by fingernails or a sharp object that the child had secretly made during long nights of despair. It wasn’t a name, but a crude drawing of a wide-open eye, and beneath it, a scrawl: “She sees. She is in my head.” On the mattress lay a single item left behind.

The small wooden horse Clara had given Samuel for his birthday last year. But it wasn’t intact. The two eyes of the wooden horse had been gouged out, leaving two black, deep holes. I picked up the horse, my hand trembling. This was a message, a warning, or perhaps a simulation ritual Lydia forced the boy to perform on his toy before… “Sheriff, get down here, quick!”

The scream of the deputy echoed from downstairs. I rushed to the kitchen. Under the dining table, the rug had been pulled back to reveal a secret trapdoor I had never noticed before. The heavy wooden door was open, and a blast of cold, foul air rushed up. It wasn’t the smell of potatoes or aging wine.

It was the smell of rusty iron, dried blood, and the pungent odor of preservative chemicals. I shone my flashlight down the wooden steps leading into darkness. The cellar wasn’t large, only about ten square meters with damp earthen walls. But what it contained far exceeded my imagination of rural crime.

In the middle of the cellar was a sturdy wooden chair with large armrests. Fastened to the legs and arms were small leather straps and iron chains—sized for the wrists and ankles of a child. I stepped closer, shining the light on the leather straps. They were worn, and on the inside, dried black bloodstains clung to the leather grain. Samuel had been tied here. The boy had been imprisoned in this dark, damp cellar.

Turned into a living test subject. In the corner, on a small shelf makeshift-nailed into the dirt wall, I found a row of small glass jars. Most were empty, but drops of amber liquid remained. And in one jar lying on the ground, perhaps dropped in haste, I saw something floating in the cloudy solution: an animal eye.

No, Dr. Arthur later confirmed to me, the structure was too similar to a human eye. Though it had shriveled significantly. But what haunted me most wasn’t the blood or the jars, but the scratch marks on the dirt wall right next to the chair. Crisscrossing scratches at the height of a sitting child’s hand.

Samuel had clawed at the earth, clawed until his fingernails bled in agony when there was no sedative. And in a hidden corner, I found a small crumpled piece of paper. Opening it, it was a page torn hastily from a Bible, the passage about the sacrifice of Isaac. But someone, likely Lydia, had used red ink to cross out all the words, leaving only one sentence: “The eye is the lamp of the body.”

Standing in that cellar reeking of death, I realized I was too late. Samuel wasn’t taken to get a glass eye. The boy was taken to complete what Lydia called “the transference.” These chains, this chair, they were proof that Lydia’s cruelty wasn’t impulsive. It was a process—a cold, systematic process to strip not just the sight but the soul of a child. And Elias… his disappearance and his manic behavior that afternoon…

I sensed he didn’t run away with his wife and son. He was left behind. Or worse, he had become part of this clean scene in some way we hadn’t yet found. I walked out of the cellar, inhaling the fresh spring air, but still felt nauseous.

It was fully dark. The Thorn Hollow house stood there, towering and black like a giant tomb. We had let the monster escape. Lydia Vane had fled, taking Samuel—the poor “vessel” still breathing—with her. And I knew the hunt was only just beginning. But the hope of finding Samuel intact had vanished like a soap bubble.

What remained was only the horror of what she would do next. When darkness completely covered the boy’s remaining eye. In the days that followed, the county post office became my second home. I sat there, eyes glued to the telegraph machine, waiting for any signal from the outside world.

We sent dozens of urgent telegrams to sheriffs in neighboring counties, describing a woman in a black dress and a one-eyed child. And then, on May 6, 1914, a fragile ray of hope flashed from Joplin, a hundred miles west. Horace Jenkins, a seasoned station master in Joplin, sent the report. Horace was a man with hawk eyes.

He remembered the face of every passenger stepping onto his train. In the detailed letter sent afterward, he recounted seeing a woman and a boy matching our description perfectly. But details in Horace’s account turned my hope of finding Samuel into a new terror.

Horace described the woman as no longer having the rustic look of a mountain seamstress. She wore an expensive silk dress, a stylish hat with a veil, exuding the air of a wealthy widow. As for the child, Horace wrote: “That boy, Sheriff… He looked more like a doll with a broken spring than a human being.”

“He sat on the waiting bench motionless for two hours. He didn’t look at the train, didn’t look at the paperboys. He wore a black eye patch, and his remaining eye stared fixedly into indefinite space. When I tried offering him a candy, he didn’t react. Only when the woman lightly touched his neck—a very light touch—did the boy startle and shake his head in refusal.”

The most haunting detail was about their luggage. When a porter accidentally dropped the woman’s leather bag, the clasp popped open. Horace swore he saw inside not clothes or jewelry, but shiny metal instruments wrapped in velvet. Scalpels. Sheriff.

Horace affirmed: “I saw them in field hospitals. Sharp, spotless scalpels.” When questioned, she coldly said they were keepsakes of her late doctor husband. But her eyes at that moment… they were sharper than knives, looking as if she wanted to carve me up for prying. But the most important detail, the one that twisted my guts, was Horace confirming they traveled alone. Absolutely no sign of a man with them. Elias Thorn was not on that train.

If Elias didn’t go with his wife and child, and if he was no longer in the house, where was he? That question dragged me and the search team back to Thorn Hollow. This time, we didn’t just search the house; we turned over the entire forest surrounding the farm. We mobilized bloodhounds. The best trackers in the region.

On May 12, the dogs began barking frantically at a limestone ravine about half a mile from the main house. It was a shallow cave hidden by dense briars and rocks piled up hastily. The smell of death rose pungently, overpowering the damp moss. When we removed the camouflage rocks, the naked, brutal truth of Elias Thorn’s fate was exposed.

Elias lay curled in a fetal position, but his death was not peaceful. The coroner’s report later was the hardest document to read in my career. Elias had been bound. Deep purple bruises on his wrists and ankles showed he had been tied tightly to a fixed object. Likely the chair in the cellar for a long time before death.

He died of starvation, exhaustion, and head trauma from a blunt object. But that wasn’t the most terrible thing. Dr. Arthur, face ashen as he stepped out of the exam room, told me: “Silas, she practiced.” “Practiced what?” I asked, though deep down I vaguely guessed. “On Elias’s eyes.” Arthur trembled lighting a cigarette, his hand unable to steady the lighter.

“Both his eyes were removed. But not eaten by wild animals, nor by natural decomposition. They were cut out. Sharp, precise cuts to the millimeter, separating the eyeball from the socket without damaging the eyelids. Silas… based on tissue retraction and hematoma…” Arthur paused, taking a deep breath for courage. “She did it while Elias was still alive.” I felt sick.

I had to grab the edge of the table to keep from collapsing. Elias Thorn, that poor man, spent the final moments of his life in a living hell. He had been tied to a chair by his own wife and forced to open his eyes one last time to see her scalpel descend. Why? To punish him for trying to ask Clara for help? Or simpler, crueler… she needed practice.

She needed to ensure that when she performed the final ritual on her precious “vessel,” Samuel, she wouldn’t make a mistake. Elias was just a draft, a piece of meat for her to hone her butcher skills. Based on decomposition, Arthur concluded Elias died about three to four weeks before being found.

That matched horrifyingly with Clara Halloway’s last visit. It meant right after Clara left that afternoon, when Elias panicked and revealed a vulnerability, Lydia struck. She killed her husband, hid the body in the cave, then calmly returned to the house, cleaned the blood, packed, and led Samuel to the train as if going on vacation.

We immediately issued a nationwide warrant for Lydia Vane or whatever name she was using. The press began calling her the “Eye Collector of the Ozarks.” But you know, in 1914, the world was in chaos; World War I was about to erupt, attention focused on Europe.

Communication between states was fragmented. Lydia Vane, with her cunning and masterful disguise, exploited those cracks to evaporate. Springfield police helped investigate her past, and the result was a vast blank. No birth certificate, no tax records. The name Lydia Vane was fake.

The recommendation letters she gave the tailor shop were fake. She was like a ghost with no past, appearing only to sow disaster and then dissolving into the night. Every night I dreamed of Elias. In the dream, he stood at the foot of my bed, two empty sockets weeping black blood, mouth mouthing a question I could never answer.

“Why didn’t you come sooner?” And then the image shifted to Samuel. The boy sitting on a train speeding west, toward strange cities where no one knew his stepmother’s crime. He sat there waiting in silence until Lydia decided her skills were perfect enough to take what remained of him. We found the father’s body, but the child…

The child was still in the hands of the devil. And I knew Samuel’s time was counting down by the day, by the hour, with every turn of the train wheels. Time is a strange medicine. They say time heals all wounds. But for the Thorn Hollow case, time was just like dust covering a keloid scar—ugly and itching whenever the weather turned.

1914 passed, taking with it the cold of winter and my shameful failure. World War I broke out, the whole world engulfed in smoke and fire, and the story of a missing child in the Ozarks gradually sank into oblivion. But for me, Silas Crow, it never ended.

In August 1915, a year after we found Elias’s body, a strange package was sent to my office. No sender name, just a scrawl on the outside: “Found by the White River after the spring flood, perhaps belongs to the case you are looking for.” Inside the package was a leather-bound diary, swollen from water. The smell of river mud mixed with mold.

It was Lydia Vane’s diary. I spent nights by the oil lamp, using a magnifying glass to decipher each blurred line. And what I read made me—a man who didn’t believe in ghosts—tremble. The diary wasn’t the musings of a lonely woman.

It was the record of a mad scientist, a fanatic believing in ancient dark arts I thought only existed in scary stories for children. Lydia didn’t choose Elias randomly. She chose him because Mary, the first wife, had died. In the diary, Lydia wrote that Mary belonged to a lineage of women with “The Sight”—The Seers, who could see the future and the past.

And Samuel, the son carrying Mary’s blood, was the perfect vessel she had sought all her life. “The right eye is the door,” Lydia wrote on June 10, 1913. “I have opened that door. I have tasted his memories. I see what he sees. The yellow dog, the old oak, and the longing for his mother… but not enough. The left eye, the left eye is the soul. When I take the remaining left eye, when darkness completely covers him, I will become him. I will see everything.”

Reading that, I felt nauseous. Samuel wasn’t a human in that woman’s eyes. The boy was just a replacement part. A living battery for her to charge her insane delusions. The care, the sedatives, the brainwashing—all were preparation for the final transference ritual.

She believed that by taking Samuel’s eyes and preserving them with a special formula, she could see through the world via another’s eyes. The diary ended abruptly on May 17, 1914, the day she killed Elias and fled. The last line read: “Elias has no more value; the vessel and I will go west.”

“There, I have prepared a cleaner cellar. The full moon comes; the ritual will be complete.” I issued a warrant based on clues in the diary, but it was hopeless. Lydia Vane was too smart, too cunning. She was like a snake that shed its skin and slithered into the brush. It wasn’t until 1937, over 20 years later, when I had retired and was living my final days in regret, that another piece of the puzzle was found. When road workers dug up a wasteland near Springfield city, where a house had burned down years ago, they found a secret cellar. Beneath that pitch-black earth lay the skeletal remains of a child.

Forensic examiners said the child was about 13 when he died; the bones showed severe malnutrition. But the detail that made me weep right at the scene was the two eye sockets. The orbital bones showed signs of partial healing, meaning the child had lived.

He had lived in total darkness, blind and in pain. At least one to two years after having both eyes removed before being killed and buried in this cold ground. Near the skeleton, they found a metal button. A school uniform button that Samuel wore on his last day of school.

The boy died in solitude, in eternal darkness. Just as Lydia planned, the case was legally closed. The perpetrator was presumed dead or vanished, but the haunting did not let me go. In 1952, when I was an old man near death, I received a letter from Nebraska.

The sender was an old nurse who used to work at the state mental asylum. She wrote to me because she read an old article about the Thorn Hollow case in the library. She told of a Jane Doe patient admitted in 1920. A blind woman with no eyes, her sockets just two deep holes scarred over.

She never gave her real name, only calling herself “The Seer.” “She was very scary, Mr. Silas,” the nurse wrote. “Though blind, she knew everything. She knew I hid a love letter in my pocket. She knew the chief doctor was having an affair. She sat in solitary confinement, facing the wall, whispering about things happening hundreds of miles away.”

“She always said she was looking through the eyes of a child, that the child was still crying inside her head.” The woman died in 1926, taking her secrets to the grave—no photos, no fingerprints to compare. But I knew in my heart, I knew it was Lydia. Perhaps that mad ritual succeeded in some twisted way.

Or perhaps she simply went mad from her own sins. She took Samuel’s light, and in the end, she too had to live and die in darkness, imprisoned by the very hallucinations she craved. Now, I sit writing these lines in my small room. Before me, the fireplace burns brightly.

In my hand is Lydia’s leather diary. I should have turned it over to the State Archives or burned it the first day I got it. But I didn’t. I kept it as a reminder of my own failure, of the price of indifference and cowardice. But tonight, I will burn it. I cannot let this dark magic exist one more day in this world.

I throw the diary into the fire; the pages curl and blacken, and in the crackling of the flames, I swear I hear a scream—not Lydia’s, but the pitiful cry of Samuel echoing from the past. The fire swallows the book, turning crimes into ash. But my friends, as I look into that pile of ash, I still feel a chill down my spine.

I feel as if from the dark corner of this room, from the thick night outside that window, a blue eye is wide open, staring at me. The eye of a child who never got to grow up. An eye that saw the true face of evil, and now it looks at me in judgment.

The story of the Thorn family ends here. Thorn Hollow is now just a wasteland; the forest has swallowed the foundation of the old house. But the people of the Ozarks still whisper to each other: never go into that forest when the fog descends. Because in that milky mist, you might encounter a boy looking for his eyes.

Or worse, you will meet a woman with no eyes who sees all the deepest sins in your soul. Take care, and pray that the darkness never looks back at you when you look into it. The story of the Thorn family closes, but its echo will likely remain long in our minds.

Transcending the fear of dark forces or human cruelty, the greatest lesson Silas Crow left behind is the expensive price of indifference and silence. The tragedy at Thorn Hollow didn’t begin with Lydia’s scalpel; it began when neighbors, the holders of justice, tutted and ignored their intuition because they feared being a nuisance, feared interfering in others’ privacy.

In this hurried modern life, we easily make similar mistakes. Sometimes we see signs of instability in a child, a neighbor, or a colleague, but choose to look away because we think it’s none of our business.

Remember that evil often doesn’t appear with hideous claws at the start; it often hides behind the most perfect, clean, and polite exteriors. Your intuition is a warning light. If you feel something isn’t right, be brave enough to stop and observe closely. A look of concern, a timely question, or a determination to defend what is right can sometimes save an entire life, preventing a tragedy before it happens.

Don’t let hesitation turn us into unintended accomplices of the darkness. Live with a warm heart and eyes always open to the pain of others. If today’s story touched your emotions, leave a comment below with your thoughts or suggest mysterious cases you want to hear in the next video.

News

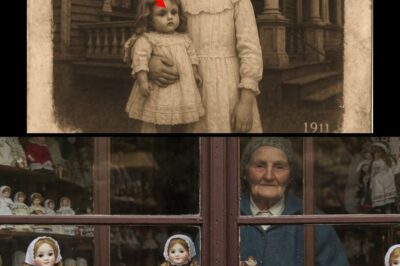

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

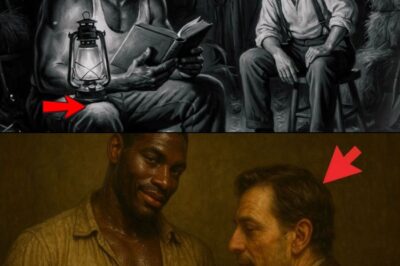

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load