The punishments in the Byzantine arenas were so brutal that even the Romans were horrified and wanted to erase them from history.

She’s already on her knees when the gates open. Hippodrome of Constantinople. Summer, midday heat. The sky is empty and hard. No clouds, no shade. Stone seats rise all around her like a wall of faces. 50,000 people are packed into those seats. Some are standing, some are leaning forward. All of them are looking at one point. Helena, 23 years old, born into a noble blue family, now kneeling alone in the center of the arena. Her wrists are bound in front of her with iron. Her ankles are shackled so tight she cannot stand, cannot turn. If you’re drawn to real history, where innocence is destroyed in silence, comment where you’re watching from and stay with me.

The chain forces her into one posture: low, exposed, on display. She can feel the sand burning through the skin on her knees and palms. She has been here long enough that the pain no longer feels sharp. It feels distant, like it belongs to someone else. The noise around her never stops. People shout to each other, laugh, argue. They’re not talking about races. There are no chariots on the track. They’re talking about her, guessing what will happen, betting on how long she will last, trading rumors about what she did to deserve this. Helena does not know what they have been told. She was not given charges. She was not given a sentence. All she was told was to kneel and not move.

Then the sound changes. Behind her, metal scrapes against stone. A heavy gate slides open. Voices shout in commands she cannot make out. There is the clatter of hooves on solid ground. Then the dull thud of those hooves hitting sand. The crowd reacts instantly. The noise rises like a wave: rough, excited, hungry. Helena twists as far as the chain allows. She cannot turn fully. She can only see out of the corner of her eye. Dust, movement, something large and dark. Then she hears it breathe: low, rough, close. A bull. They have brought a bull into the arena and they are driving it toward her. This is not a random cruelty. This is not a simple execution. This is a staged moment, a message. And this is still not the worst part.

The bull walks slowly, deliberate steps guided by handlers with ropes and poles. It is not charging. It is not confused. It is calm. The handlers keep it just far enough away that Helena can’t feel it yet. Only hear it. Only imagine it. The crowd starts to chant now. Not for her. For the moment. For the moment they paid to see. Helena’s breath comes in short bursts. Her shoulders shake. Her hands are trembling against the chains. She tries to think of anyone she knows in the stands. Family, friends, people who shared meals with her. Are they watching? Do they look away? Or are they leaning forward like everyone else? The bull stepped closer. She can hear the sound of its breathing more clearly now. The weight of it, the power in each exhale. Someone in the stands shouts her name. Not kindly. Helena drops her head. She does not know yet that this moment is not about killing her body. It is about killing something else: Her name, her standing, whatever future she might have had.

She does not know that other people have already died in this arena this week. She does not know that the men watching from the shaded imperial boxes above believe this is the safest way to control a city. She only knows this: The bull is behind her now, close enough that she can feel the heat of its presence, though it has not touched her and nobody moves to stop any of it. This is not the moment when things went wrong. This is the moment when the system worked exactly as designed.

To understand why Helena is here, you have to understand what this place really is. The Hippodrome was built to look like entertainment. 400 meters of track. Stone seating for tens of thousands. An ornate imperial box, the kathisma, where the emperor and his court sat above everyone else. On race days, the arena was full of color. Blue and green banners, chariots painted with symbols, drivers treated like celebrities. But under the surface, something else was happening. Beneath the sand, there were corridors and chambers, storage rooms, holding cells, hidden passageways that allowed guards to move people in and out without the crowd seeing. The Hippodrome was not only an arena. It was infrastructure. A place where the emperor could look down and see the entire city gathered in one space. A place where loyalty could be measured by where people sat, what colors they wore, how loudly they cheered. A place where obedience could be rewarded publicly and where disobedience could be punished just as publicly.

What you are watching happen to Helena did not begin with her arrest. It began with the factions. In Byzantine Constantinople, people were not just citizens. They were blue or green. Originally, these were the teams that raced chariots. Over time, they became something much more. They turned into political parties, street gangs, religious pressure groups, private security forces. If you were born into a blue family, you expected to live and die blue. If you were green, the same. They had their own leaders, their own meeting halls, their own ways of enforcing discipline. They could organize quickly. They could fight in the streets. They could turn a crowd into a weapon. The Hippodrome was where this loyalty became visible. Blue sat on one side, green sat on the other. You wore your colors. You cheered for your team. You joined in the chants. If you stayed silent, people noticed. If you cheered at the wrong time, people noticed. And when the emperor looked down from his box, he saw more than chariots. He saw a map of his city’s loyalties. He saw who might support him, who might resist, who might be persuaded or punished. The factions gave emperors a powerful tool. Promise favor to one side, threaten the other, play them against each other so they never unite. Most of the time this balance held. But when it broke, the Hippodrome became something else entirely.

It broke in the year 532. Taxes had risen. Religious conflicts had sharpened. Resentment simmered in every district. The Blues and Greens were both angry. Not with each other, with Justinian, the emperor. For once they shouted the same word: Nika. Victory. Not victory on the track. Victory over the man in the purple robes. On January 18th, the Hippodrome was packed. Chariots were ready. Drivers stood by. None of it mattered. The crowd turned away from the starting gates and toward the Imperial box. Tens of thousands of voices merged into one chant: Nika, Nika, Nika. They demanded that Justinian dismiss corrupt officials. Lower taxes. He did hear them. He just did not answer the way they expected. At first, officials were sent to negotiate. They were shouted down, forced to retreat. Then Justinian made a choice. He ordered the gates sealed. Every exit. Every passageway that led out of the arena, locked.

People only realized slowly. At first, the chanting faltered. Then it stopped. Confusion spread. Some tried to leave and found the way barred. Panic spread through the stands. They were trapped, not at a race, in a container with an emperor who had decided to solve his problem in the most direct way possible. Whatever you imagine happened next, the reality was worse. Justinian summoned his best general, Belisarius, a man who would later be famous for campaigns against foreign enemies. That day, his army’s target was inside the capital, inside the Hippodrome. He entered through a passage beneath the arena with 3,000 soldiers: heavy infantry, shields, short swords, spears, no archers, no long-distance weapons. What was about to happen would be up close. The soldiers formed a line across the arena floor. Then they began to move up into the stands. The people trapped inside had no weapons, no armor, no training. Most had come expecting races, a day out. Noise and spectacle, but not this kind. As soldiers advanced, some tried to fight with bare hands. Some tried to climb the walls. Some tried to break through the locked gates. They failed. Row by row, section by section, the soldiers moved with methodical focus. They were not there to scare. They were not there to injure. They were there to kill. By nightfall, somewhere between 25 and 35,000 people were dead. No graveyard could hold that number. The Hippodrome itself became a mass grave. The message was simple: Do not unite against the emperor ever.

The survivors carried that memory home. They told their families. They told their children. But while soldiers were killing the crowd, something else was happening in the stands. Officials were moving through the chaos with lists. They were looking for specific people, leaders, spokesmen, wealthy backers of opposition, and the families connected to them. Some of these people were pulled aside. Not killed, not yet. They were kept for something more precise, more personal, more visible. The massacre was only one part of what the Hippodrome was built to do.

After the mass killing, the arena was quiet for a few days. Then it reopened. Races were not on the schedule. A different kind of performance was planned. 73 women had been taken alive from the stands during the chaos. Wives and daughters of men who had spoken too loudly or stood in the wrong place at the wrong time. They had been kept beneath the arena. No proper beds, no privacy, little food, less water. By the time they were brought up, they were weak. That was intentional. The crowd that day was smaller, around 10,000. But those 10,000 had been chosen. They were loyal. They were influential. They would repeat what they saw. The women were marched out through the gates. Four days earlier, many of them had watched the riots from the best seats, wearing fine clothing. Now they wore rough garments. Their hair had been hacked short or shaved, faces bruised, eyes red from lack of sleep. They were paraded around the track in a line. Guards walked on either side. A herald announced their names and supposed crimes: supporting treason, encouraging rebellion, failing proper obedience. The crowd was urged to respond. They shouted insults. They threw what they had. Rotten food, clouds of dirt. Whatever could sting without leaving obvious permanent marks. The women were forced to complete the entire circuit of the track, 400 m. If any fell, they were pulled back to their feet. They were not allowed to shield their faces, not allowed to speak, not allowed to look away. At the end, they were brought to the center of the arena and made to kneel. Their sentences were read: Exile. Confiscation of property, loss of status. They lived, but the people in the stands did not remember them as living people. They remembered them as examples. This is what happens to women who stand too close to the wrong men who fail to keep their place who are present when power is challenged. Their families lost more than land. They lost a future. You are watching the same process being applied to Helena. Her punishment is not about blood. It is about erasure.

The Nika massacre changed something in Constantinople. The Hippodrome did not go back to being just a racetrack. It proved how effective a single public space could be for controlling an entire population. From then on, it became one of the empire’s main stages for political punishment. Some of these punishments were quick. Blinding, for example. The Byzantines used blinding as a way to remove rivals without killing them. If a man could not see, he could not lead armies. He could not read documents. He could not sit confidently in the imperial box and look down at the people below. But he could walk through the city as a warning. People would see him and remember. Romanos IV, a former emperor, is one of the most famous cases. After military defeat and political betrayal, he was brought to the Hippodrome. The crowd gathered to see what would be done. His crimes were read aloud. Not just failure, danger. Endangering the empire itself. Then his sight was taken, not in a hidden room, not in private, in front of people who understood that they could be next if they backed the wrong man. The accounts do not linger on every detail. They do not have to. Everyone present knew what it meant to watch a man walk into the arena one way and be led out another: Alive, but reduced. Blinding was efficient.

The methods developed in the Hippodrome went further. Sometimes chariots themselves became tools of punishment, not for winning races, for ending lives. A rebel or assassin might be tied behind a chariot instead of seated inside it. Arms bound, legs secured, then the horses would be driven around the track, not at full racing speed, slower. Slow enough for everyone in the stands to see the body jerk with each movement. Slow enough for the punishment to last. People knew what sand and stone could do to a human body dragged across them. The point was not to surprise the crowd. It was to show exactly what happened to those who challenged power. Word of such executions traveled quickly. You did not need to see one to picture it. You only had to hear the way survivors talked about them carefully, quietly. Helena grew up hearing stories like these. They were meant to keep her far away from politics. They did not.

Not all spectacles involved blood. Many focused on public humiliation, especially when the target was a woman of status. Execution could create a martyr. Humiliation broke people without giving them anything heroic to cling to. The ritual called the procession of shame followed a pattern. A noble woman might be accused of adultery or suspected of witchcraft or simply be connected to the wrong faction. She would be arrested, held below the arena, and stripped of everything that marked her rank. Her elaborate hairstyle cut off, her fine clothing replaced with something plain and rough. Her jewelry removed. Then she would be brought into the Hippodrome, not during an empty afternoon. During a day when people were already gathered, she would walk the circuit of the track while her name and supposed offense were shouted out. The crowd was encouraged to jeer, to insult, to laugh, to point. At the end, like the women after the Nika riots, she would kneel in the sand. Her sentence might be exile or confinement to a convent, rarely execution. The goal was not to end her life. It was to end her identity. From that day on, people would remember her not as a noble woman, but as the subject of a public spectacle. Her name would become a shorthand for disgrace. Theodora, the powerful empress, married to Justinian, understood this system well. She had grown up on the edges of the Hippodrome’s world. Not noble, not respected. When she gained power, she used the arena against women who had once insulted her. They were brought in, paraded, shamed, erased, then sent away. Their social deaths were complete before their physical deaths ever came.

All of this history is hanging in the air as Helena kneels in the sand. She knows what this place can do. She has seen people led into the Hippodrome and come out different or not at all. She knows there are cells beneath her feet, tunnels, storage rooms. She knows men in fine clothing are watching from the shaded imperial boxes above. The bull behind her does not know any of that. It only knows the pressure of the handler’s ropes and the sound of their voices. It snorts, shifts its weight, steps closer. Helena can feel the vibration through the ground now. Her breathing speeds up. For her, this is not an abstract lesson in power. It is a direct personal terror. She believes she is about to die. Not later. Now. She believes that whatever story is being told to the crowd with her body will end in her death. The guards do nothing to correct that belief. That is the heart of this spectacle. They let her mind run through every possible horror. They let the crowd project their own ideas of what might happen. They let fear do most of the work.

The bull’s head lowers slightly. The crowd leans forward. This is the moment they will talk about later. Did she scream? Did she stay silent? Did she beg? These questions matter more to them than what actually happens. The handlers keep the bull just close enough. Helena can feel its breath on her back. She screams. The sound cuts through the arena for a moment. Then it is swallowed by the roar of the crowd. The bull does not touch her. It never will. That was never the plan. Minutes pass. They feel like hours. Helena’s muscles shake from tension. She tries to brace herself for impact. That never comes. The chains dig deeper. Her knees ache. Her throat burns. Above her. In the shaded seats, men watch carefully. Not for the bull. For her. They are looking for the exact moment her posture changes. The moment her back curves differently. The moment her head drops in a way that says clearly that something inside her has broken.

When they see it, they give a signal. The handlers pull the bull away. It resists at first, then turns, guided toward the gate. The sound of its hooves recedes. The crowd’s noise changes again. Some laugh, relieved that they did not witness something messier. Some jeer, disappointed. Some fall quiet, unsettled by the fact that nothing visible happened and yet something clearly did. Helena collapses forward onto her hands. She is still alive, still in one piece. But she is not the same person who entered the arena. She has been turned into a story, a warning, a name people will say when they want to explain why certain women do not speak up. Why certain families stay away from politics. Why certain friends decline invitations to meetings that sound even slightly risky. Helena is led away in chains. She is exiled soon after. She dies young. Her official cause of death is not recorded. It does not need to be. As far as the empire is concerned, the part of her that mattered died in the Hippodrome.

The ruins of the Hippodrome still exist in modern Istanbul. Tourists walk along the old track, sit on benches where stone seats once rose, take photos of columns and fountains. Few of them think about what this place was built to do. They see it as a historical site, an impressive remnant of a vanished empire. They do not see it as a machine. But that is what it was. A machine for turning power into spectacle, for turning citizens into an audience, for turning dissent into warning stories everyone would repeat. The Byzantines saw themselves as civilized, educated guardians of law and faith. They preserved Roman legal traditions, copied ancient texts, built churches that still stand today. And they did this. They used a public arena to kill tens of thousands in a single day. To blind rivals, to drag bodies behind chariots, to strip women of identity in front of crowds, to break people like Helena without laying another hand on them. That contradiction matters. It shows that civilization does not erase cruelty. It refines it, makes it efficient, careful, strategic.

The Hippodrome is gone as a working arena, but the pattern it represented has not disappeared. Modern states still use public examples. They still humiliate opponents. They still stage events that teach people what happens when you challenge power. Sometimes the arena is a courtroom broadcast on television. Sometimes it is a press conference. Sometimes it is a social media storm. The tools change, the logic does not. Helena does not have a grave people visit. Most of the victims of these spectacles do not. Their names are scattered through chronicles if they appear at all. But the system that destroyed them can still be studied and understood and recognized when it tries to appear again.

The most effective terror does not always aim for the body. It aims for identity. It makes sure that when a person walks out of a space, they are not who they were when they walked in. That is what happened in the Hippodrome. That is what happened to the women paraded after the Nika riots. To rivals blinded on public platforms, to rebels mocked with fake crowns before execution, to Helena kneeling in the sand with a bull at her back. They all became stories, warnings.

If this story moved you, support the channel by subscribing and liking the video. The question is not whether empires will try to use these methods again. The question is whether we will recognize them when they do and whether we will stand in the crowd and watch or refuse to be part of the spectacle.

News

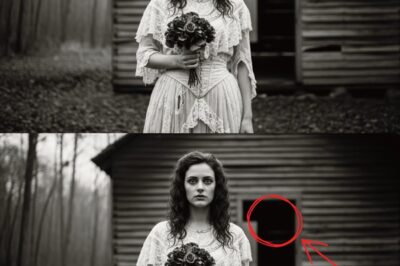

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22)

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22) Welcome to this journey through one of the…

The Mill Creek Mother Who Closed the Windows – The Chilling 1892 Case That Shocked a Town

The Mill Creek Mother Who Closed the Windows – The Chilling 1892 Case That Shocked a Town On the cold…

The depraved rituals that Egyptian priests performed on virgins in the temple made them want to erase them from history.

The depraved rituals that Egyptian priests performed on virgins in the temple made them want to erase them from history….

What they did to Anne Boleyn before her execution was so horrific that they wanted to erase it from the historical record.

What they did to Anne Boleyn before her execution was so horrific that they wanted to erase it from the…

Pregnant at 13 With England’s Future King – The Tragic Story of Lady Margaret Beaufort

Pregnant at 13 With England’s Future King – The Tragic Story of Lady Margaret Beaufort Picture this. A girl’s scream…

How Nero Turned a Teenage Boy Into His Dead Wife

How Nero Turned a Teenage Boy Into His Dead Wife The Imperial guards found him hiding in the abandoned villa’s…

End of content

No more pages to load