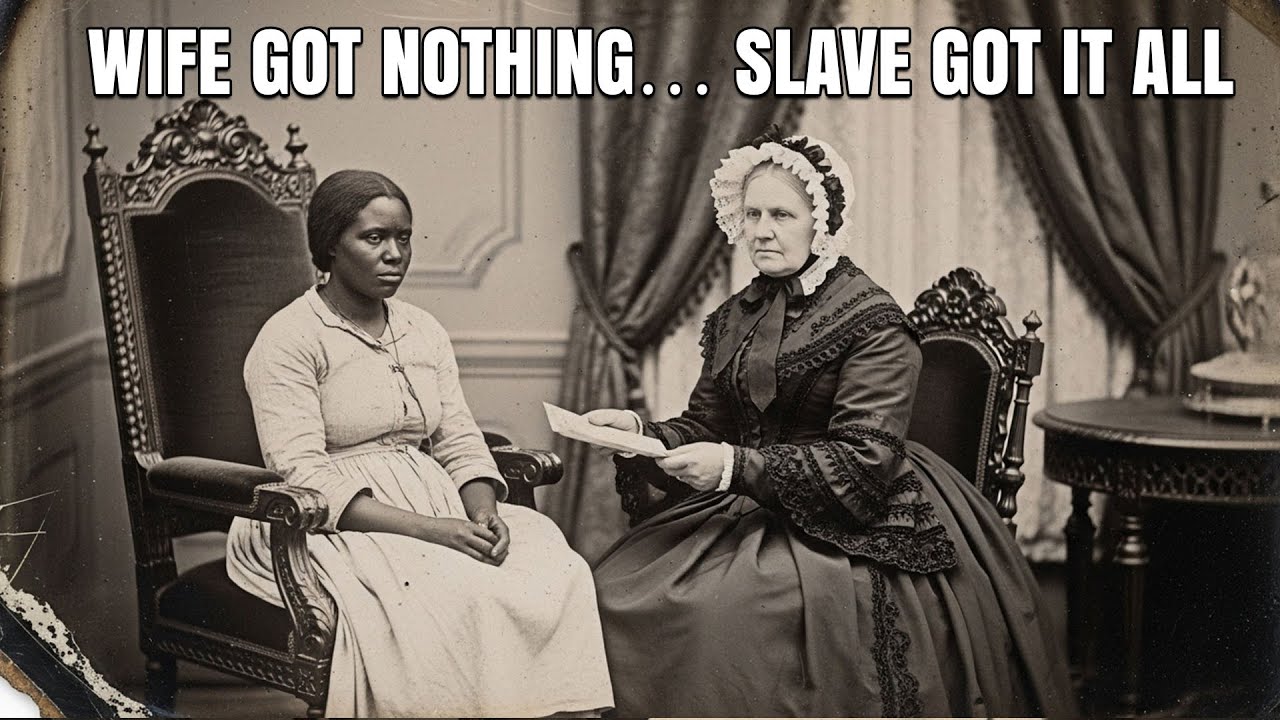

The Plantation Master Who Left His Fortune to a Slave… and His Wife with Nothing

The attorney’s hands trembled as he broke the wax seal. It was June 17th, 1854, and the parlor at Belmont Manor in Nachez, Mississippi, had never been so silent. 15 people sat in that room watching James Whitfield unfold a document that would ignite a scandal so explosive. It would make headlines from New Orleans to New York and force a court case that would drag on for seven brutal years.

Margaret Thornton sat in the center chair draped in black morning silk, her face a mask of composed grief. She’d buried her husband of 23 years just 3 days earlier. Around her sat their four children, her brother-in-law, her sister, two family attorneys, and several prominent witnesses from Nachez society.

All there to ensure the proper transfer of one of Mississippi’s largest cotton fortunes. What none of them knew was that in approximately 4 minutes, Margaret Thornton’s entire world would collapse. Because the man they’d just buried, Plantation Master Robert James Thornon, had done something that no one in that room could have imagined, something that would violate every social code of the Antabellum South.

Something that would force them all to confront truths they’d spent lifetimes pretending didn’t exist. But before we continue with what happened in that parlor and why Robert Thornton’s final act would tear apart everything his family believed about their lives, make sure you’re following the sealed room because we bring you the true stories that history tried to bury, the scandals that powerful families wanted forgotten and the human dramas hidden beneath the surface of America’s past.

Drop a comment and tell us what you think drives a man to destroy his own legacy. Is it guilt, love, revenge, or something more complicated than any of those words can capture? Attorney Whitfield cleared his throat. Ladies and gentlemen, I must warn you that the contents of this testament are highly irregular. Mr. Thornton insisted I read every word exactly as written without omission or summary. Margaret’s sister, Caroline whispered. Just get on with it. James, we’ve had enough drama. They had no idea. Whitfield began reading the standard opening. the declarations of sound mind, the revocations of previous wills. Margaret’s posture relaxed slightly. Her oldest son, Robert Jr., aged 22, leaned back in his chair, already mentally calculating what he’d do with Belmont’s 3,000 acres. Her daughters, Elizabeth and Anne, both unmarried and in their 20s, exchanged glances that spoke of relief. Their future was secure, their marriage prospects safe.

Then Whitfield reached the first bequest and his voice changed, became strained. To my wife, Margaret Elizabeth Thornton, I leave the sum of $1 to be paid within 30 days of my death. The room froze. Margaret’s face went white. That’s There must be some mistake. Mrs. Thornton, please let me continue. $1. James, check the document again. Robert wouldn’t. To my sons, Robert James Thornton, Jr. and William Charles Thornton. I leave the sum of $1 each to be paid within 30 days of my death. Whitfield’s voice was barely above a whisper now. To my daughters, Elizabeth Margaret Thornton and Anne Caroline Thornton. I leave the sum of $1 each to be paid within 30 days of my death. Robert Jr. surged to his feet. This is insane. Father had over $400,000 in assets.

The plantation alone is worth please sit down, Mr. Thornton. Whitfield wasn’t looking at any of them now. His eyes were fixed on the paper, and his hand holding it had begun to shake visibly. I must read the primary bequest. The silence in that room was the kind that comes just before a storm breaks. The kind where you can hear your own heartbeat pounding in your ears.

The kind where every person present knows with absolute certainty that their life is about to change forever. To Eliza Marie, Whitfield read, his voice cracking on the name. A woman of approximately 32 years of age, currently held as property at Belmont Manor. I hereby grant immediate and unconditional freedom.

Furthermore, I grant to the aforementioned Eliza Marie the entirety of Belmont Plantation, including all 3,100 acres of land, all buildings, all equipment, all livestock, and all crop yields current and future. Someone gasped. Margaret made a sound like she’d been struck in the chest, but Whitfield wasn’t finished.

I further grant to Eliza Marie my full ownership stake in Thornton Cotton Factoring Company, my shares in the Natchas Railroad Company, my property holdings in Natchez City proper, including the house at 42 Pearl Street, all bank deposits, all bonds, all securities, all personal property of every kind and description, and all currency in any form.

Margaret stood up so fast her chair toppled backward. No, no. This is forgery. This is James. You wrote this yourself. You’re trying to steal. Mrs. Thornton, I did not write this will. Your husband came to my office 6 weeks before his death and dictated it to me personally. I advise strongly against these provisions. He was adamant.

6 weeks? Margaret’s voice rose to a shriek. 6 weeks he sat in this house, ate at my table, let me plan his future, and he’d already written me out of everything. Elizabeth, the older daughter, had started to cry. Anne sat perfectly still, her face blank with shock. William, the younger son, looked like he might be sick.

But Robert Junior’s face had gone dark red, the veins in his neck standing out. “Who?” he said, his voice dangerously quiet. “Is Eliza Marie?” And that was the question, wasn’t it? The question that would unravel everything, because everyone in that room knew exactly who Eliza Marie was.

They’d just never allowed themselves to think about what she actually meant. Whitfield set down the will and looked at Margaret. What he saw in her face made him flinch. Mrs. Thornton, perhaps the ladies should Don’t you dare. Margaret’s voice was ice. Don’t you dare tell me to leave. This is my house. These are my children, and you’re going to explain to me how a woman who was property yesterday now owns everything I’ve spent 23 years building. I’m not finished reading, Whitfield said quietly.

There’s more, Williams voice cracked. I further declare, Whitfield read, and his hands were shaking so badly now the paper rattled, that the following children, currently living at Belmont Manor, are my natural offspring and are to be freed immediately upon my death and provided for from the estate. Marcus, age 9, Sarah, age 6, and Thomas, age three. The room exploded. Robert Jr. started shouting. Elizabeth collapsed into sobs. Margaret stood frozen, her mouth opening and closing without sound. Because what Witfield had just read wasn’t just about an inheritance. It was about three children everyone at Belmont had seen, had known about, had carefully pretended not to understand the significance of.

Three children who all had light-kinn and distinctive features. Three children who looked unnervingly like the Thornon family. Three children who were Robert Thornton’s sons and daughter, born to the woman who now owned everything, Caroline. Margaret’s sister found her voice first.

Margaret, did you know about the children? But Margaret wasn’t listening. She was staring at a point on the far wall, her breathing coming in short, sharp gasps. When she finally spoke, her voice was barely human. Where is she? Where is this woman who stolen my life? Mrs. Thornton, Miss Eliza is not responsible for where is she? A voice came from the doorway, quiet but clear. I’m right here. Every head in the room turned.

Standing in the parlor entrance was a woman in a plain gray dress, her posture straight, her expression carefully neutral. Eliza Marie was 32 years old, though she’d never known her exact birthday. She had amber-colored eyes, dark hair pulled back severely, and skin the color of aged honey. She’d been born enslaved on a Virginia plantation, sold south when she was 14, and purchased by Robert Thornton in 1843 for what the records listed as household management duties.

For 11 years, she’d lived in a small room behind the kitchen at Belmont. She’d managed the household accounts, supervised the other house servants, raised three children in secret in the shadows, where no one would have to acknowledge what they were or who had fathered them.

And now, according to the document James Whitfield held, she owned all of it. Margaret looked at Eliza, and something terrible passed between them. These two women who’d lived in the same house for over a decade, who’d both loved the same man in whatever twisted forms love could take in a world built on ownership, who’d both born his children, who’d both constructed careful performances of their roles, mistress and servant, wife and property, each pretending the other didn’t threaten everything she’d built her identity around. “You knew,” Margaret whispered. “You knew he was going to do this.”

Eliza’s face remained impassive. He told me 3 days before he died. 3 days. Margaret’s laugh was horrible. He gave you 3 days warning and me none at all. 11 years you’ve been in my house. 11 years I’ve fed you, clothed you, given you shelter. And this is how you repay. You never gave me anything, Mrs. Thornton. Eliza’s voice was quiet but steady. Your husband purchased me.

Everything I had, every moment of my life belonged to him. To you. I couldn’t refuse anything. I couldn’t leave. I couldn’t protect myself or my children. I wasn’t repaying anything because I never owed you anything. I was property. The word hung in the air like poison. Robert Jr. moved toward Eliza and something in his posture made Whitfield step between them. Mr. Thornton, I must advise you that any physical intimidation of Miss Eliza would be Miss Eliza. Robert Jr.’s voice dripped venom. You’re calling her miss. She’s a She is a free woman as of 3 days ago,” Whitfield said firmly. “Per the legal terms of your father’s death and the activation of this will, Miss Eliza is no longer enslaved.

She has legal standing, and she is, as of this moment, one of the wealthiest property owners in Adams County. The absurdity of it was too much for some people in the room.” One of the witnesses, a banker named Pritchard, started laughing. High hysterical laughter that sounded like it might turn into screaming. His wife dragged him from the room. Margaret was still staring at Eliza.

Why? I need to understand why. What did you do to make him choose you over his own children? And Eliza, who’d spent 11 years being careful, being invisible, being whatever she needed to be to survive, finally let something show on her face. Pain deep aching pain that had lived in her bones for so long it had become part of her structure.

I didn’t make him choose anything. Mrs. Thornton, your husband made his choices every day for 11 years. He chose to come to my room. He chose to father children he knew would be born enslaved. He chose to keep us all trapped in a lie that protected him and destroyed everyone else.

And at the end when he was dying and couldn’t lie to himself anymore, he chose to tell the truth. I’m sorry that truth has hurt you. But you’re asking the wrong person why. It was the most Eliza had ever said directly to Margaret in 11 years. And it was the moment when everything that had been carefully contained, carefully managed, carefully buried beneath southern propriety finally erupted into open warfare.

Margaret’s brother-in-law, Thomas Thornon, stepped forward. He was Robert’s younger brother, a lawyer himself, and he’d been silent until now, watching everything with calculating eyes. This will is illegitimate. It was extracted under duress from a dying man. It violates every principle of natural law and Christian morality.

It will not stand in any court in Mississippi. The will was properly executed. Whitfield said Mr. Thornton was of sound mind. He had every legal right to dispose of his property as he she can’t own property. Thomas’s voice cut through the room like a knife. The law is clear.

A negro, even a freed negro, has severely limited property rights in Mississippi. She certainly can’t inherit a plantation. She can’t own enslaved people. She can’t manage business interests. The will is legally impossible. Your brother anticipated these objections, Whitfield said quietly. The will includes trust structures, guardian appointments.

Legal mechanisms specifically designed to I don’t care what mechanisms he designed. Margaret’s voice had regained its strength, though it shook with fury. This is my home, my children’s inheritance, their future, and I will burn this entire plantation to the ground before I let that woman take it. Eliza met Margaret’s eyes steadily. Then burn it, but it will still be mine when the ashes cool.

What happened next would consume seven years, destroy multiple families, expose secrets that Natchez society had kept hidden for generations, and ultimately force a Mississippi court to confront questions about property, freedom, race, and power that the entire South was desperately trying to avoid answering.

But in that moment, in that parlor with Robert Thornton three days dead and his will finally read aloud, all anyone could see was the wreckage. Margaret, who’d lost everything except a dollar in her fury. Four children who’d just discovered they were worth less to their father than the children he’d kept hidden.

And Eliza, standing in the doorway of a house she suddenly owned, with three young children she had to protect, knowing that every person in that room wanted her destroyed. The battle for Belmont Manor was about to begin, and before it was over, it would reveal truths about the antibbellum south that history books would spend the next century and a half trying to forget.

The hours after the will reading would later be described by household servants as the closest thing to war they’d witnessed without actual gunfire. Margaret Thornton didn’t leave. Legally, she couldn’t be forced to. The will granted Eliza ownership, but Margaret still had rights as the widow, even if Robert had tried to minimize them, so she stayed, and she made sure everyone knew she was staying.

That first night, Margaret gathered her children in the master bedroom, the bedroom she’d shared with Robert for 23 years, and made them swear an oath. Elizabeth would later testify in court about what her mother said. “We will fight this abomination with every legal weapon we possess. We will expose that woman for what she is.

We will prove your father was manipulated, poisoned against his own blood, and we will take back what’s rightfully ours, even if it takes the rest of our lives. But while Margaret was rallying her children upstairs, something else was happening in that small room behind the kitchen where Eliza had lived for 11 years.

Eliza sat on the edge of her narrow bed, her three children pressed against her. Marcus, at nine, was old enough to understand some of what had happened. Sarah, six, kept asking why the white lady was screaming. Thomas, just three, had fallen asleep in his mother’s lap, exhausted by the day’s chaos. “Mama?” Marcus whispered.

“Are we really free?” Eliza stroked his hair. “Hair that was softer than hers, lighter brown with reddish tints in the lamplight. Hair that came from his father. The paper says we’re free. But what does that mean? And how could Eliza explain to a 9-year-old that freedom was more complicated than a legal document? That they were free in writing but trapped in a world that would never accept that freedom.

That his father’s final act of conscience had painted a target on all their backs. She couldn’t. So instead, she said, “It means we’re going to fight to stay together no matter what happens.” What had happened between Robert Thornton and Eliza Marie was the story everyone in Natchez had whispered about for years, but never spoke aloud in daylight.

And now with the will made public, the whispers were about to become shouts. Robert Thornton had purchased Eliza in 1843 at a private sale in Natchez. The seller was a Virginia planter liquidating assets, and Eliza was listed as household trained, literate, excellent with figures. That literacy alone made her valuable and dangerous. Enslaved people who could read were watched carefully, restricted, often punished for the skill.

But Eliza had been taught by a previous owner’s wife, who believed Christian duty required education, and the skill couldn’t be unlearned. Robert paid $2,000 for her. Nearly double the standard price. His wife, Margaret, had been furious about the extravagance.

Why do we need another house servant? We have six already and $2,000. Robert, we could have bought three field hands for that price. Robert’s answer recorded in Margaret’s diary from 1843. She can manage the household accounts. You’re always saying you need help with the books. It was true. Margaret did need help. She’d never been good with numbers. Had never really wanted to be.

Running a plantation the size of Belmont involved tracking hundreds of expenditures, recording crop yields, managing inventories. It was tedious work she was happy to delegate. So Eliza took over the books, and she was brilliant at it. Within 6 months, she’d reorganized Belmont’s entire accounting system, caught errors that had been costing them thousands, streamlined the supply ordering.

Robert started consulting her on business decisions, asking her opinion on whether to invest in railroad stock, discussing cotton futures prices. Margaret noticed, of course, but she told herself it was fine. It was just business. Eliza was property, a tool Robert used to manage affairs Margaret didn’t want to deal with anyway. It meant nothing.

Then in early 1845, Eliza became pregnant. The plantation midwife, an elderly enslaved woman named Aunt Bessie, would later testify that she knew immediately who the father was. That child came out with Mr. Robert’s nose plain as day. She said wasn’t no question. And Miss Margaret, she knew, too. She just looked at that baby when he was born.

looked at Miss Eliza, then walked out the room and didn’t say one word. Marcus was born in June 1845. Margaret didn’t acknowledge his existence for the first 3 months of his life. She simply acted as if he didn’t exist, as if Eliza hadn’t given birth, as if nothing had changed. It was a performance of willful blindness, so complete that even the other servants found it unsettling.

But Robert acknowledged Marcus. Not publicly, he couldn’t, not without destroying his social standing, but privately, in small ways that everyone noticed and no one mentioned. He had new quarters built for Eliza, slightly larger, with better windows. He made sure Marcus was never assigned fieldwork, kept close to the main house.

He brought books to Eliza’s room, children’s primers, readers, mathematics texts. He was teaching his enslaved son to read, teaching him the same way he taught Robert Jr. by 1848. Sarah was born two years later in 1850. Thomas, three children in six years, all bearing unmistakable Thornton features. And through it all, Margaret maintained her fiction.

She never acknowledged the children as Roberts, never spoke to Eliza about them, never confronted her husband. Years later, in a letter to her sister Caroline written during the court battle, Margaret finally explained her silence. What was I supposed to do? Leave him and go where? Live on what? My father’s estate was entailed to my brothers. I had four children to protect. If I made a scandal, accused Robert publicly, I would have been the one society punished, not him.

Men have their indiscretions. Everyone knows this. A wife’s duty is to ignore them gracefully. I did what I was supposed to do. I maintained the household. I raised our legitimate children. I performed my role perfectly. And this is how I’m rewarded. But there was another layer to Margaret’s silence, one she never quite admitted even to herself.

Robert had stopped coming to her bed in 1844. Their youngest daughter, Anne, had been born in 1841, and after that, nothing. For 13 years, Margaret and Robert lived as married strangers. They attended social functions together. They discussed household management. They presented the perfect image of a successful planter family.

But there was no intimacy, no connection, no private life together at all because Robert was spending his private life with Eliza. And that was what made the will so devastating. It wasn’t just about money or property. It was about a husband who’d chosen someone else and had chosen her so completely that he’d given her everything Margaret had believed was hers by right.

The legal challenge began within days of the will reading. Thomas Thornton, Robert’s brother and a respected attorney in Nachez, took charge of the case. He filed a petition in Adams County Chancery Court arguing that the will was invalid on multiple grounds. First, he claimed Robert had been mentally incompetent when he dictated it.

Robert had been sick in his final months with what the doctors called consumption of the lungs, probably tuberculosis. Thomas argued the illness had affected his reasoning. Second, he claimed undue influence. Eliza had been in a position of intimate access to Robert. She’d manipulated him, seduced him, controlled him.

A dying man in her thr couldn’t make rational decisions. Third, and most importantly, he argued the will violated Mississippi law. The state had strict regulations about manumission, freeing enslaved people. Even if Robert could legally free Eliza, he couldn’t transfer property to her beyond very limited amounts.

A freed black person couldn’t own a plantation, couldn’t inherit a business, couldn’t manage enslaved workers. The will was asking Mississippi law to do something it explicitly forbade. Thomas’s petition was filed on June 24th, 1854, exactly one week after the will reading.

The judge assigned to the case was Hyram Foster, a distinguished member of the Mississippi Supreme Court who’d agreed to hear this particular case at the circuit level because of its unusual legal complexities. But everyone actually knew was that Judge Foster had been friends with Robert Thornton, had done business with him, and probably wanted to make sure the case was handled in a way that protected Natchez society’s interests.

But Thomas Thornton miscalculated something crucial. He assumed the case would be straightforward, that any Mississippi judge would immediately invalidate a will that gave so much power to a formerly enslaved black woman. He didn’t account for the one factor that would complicate everything. Robert Thornton had been extraordinarily thorough. Attorney Whitfield.

When he first met with Eliza to explain her legal position, brought a second document that hadn’t been read in that parlor, a letter Robert had written to Whitfield to be opened only if the will was challenged. Eliza sat in Whitfield’s office in downtown Natchez, wearing the same gray dress she’d worn to the will reading.

Whitfield broke the seal on Robert’s letter and began reading aloud. James, if you’re reading this, it means my family is contesting the will. I expected this. I want you to know why I did what I did, and I want you to use this letter in court if necessary.” Whitfield glanced at Eliza. She nodded for him to continue. I purchased Eliza in 1843 with specific intentions.

I had met her briefly at a previous sale, had spoken with her, and recognized her intelligence. I orchestrated her purchase deliberately. What began as a business decision became something else. something I never intended, something I tried to resist, and something I ultimately couldn’t deny.

I fell in love with someone I had no right to love, in a way our world says is impossible,” Eliza’s breath caught. Robert had never said those words to her, never told her plainly what she’d wondered about for 11 years. “I know what people will think,” the letter continued. That I took advantage of someone I owned, someone who had no power to refuse me. And they’re right.

That’s exactly what I did in the beginning. That’s what it was. Exploitation dressed up in whatever lies I told myself. But over the years, Eliza became the only person I could be honest with. The only one who saw me clearly and didn’t require me to perform. Margaret saw the planter, the businessman, the social figure.

Eliza saw the man who was terrified of dying with nothing real in his life. Whitfield paused. When he continued, his voice was thick. I have lived a coward’s life, James. I maintained a marriage that died years ago. I fathered children into bondage. My own children enslaved because I lacked the courage to do what was right.

I built wealth on the labor of people I kept in chains while pretending this was God’s natural order. And I told myself these lies because the alternative was too painful. But dying has a way of stripping away every comfortable delusion. The letter went on for three more pages. Robert detailed his instructions for how Whitfield should structure the trust arrangements to withstand legal challenge.

He acknowledged that what he was doing would hurt his legitimate children, but argued they would inherit their whiteness, their education, their social position, privileges his children with Eliza would never have unless he acted. And then at the end, Robert wrote something that would become the center of the entire case. I free Eliza not as an act of charity but as an acknowledgement of theft. I stole 11 years of her life. I stole her children’s childhood.

I stole their right to exist as human beings rather than property. This will is not generosity. It’s inadequate restitution. And if Mississippi law says a man can’t restore what he’s stolen from someone he’s wronged, then Mississippi law is more corrupted than I am. When Whitfield finished reading, Eliza sat in silence for a long moment.

Then she said quietly, “He never told me any of this, not in these words.” Men often find courage in letters they can’t find in life. Whitfield said, “Miss Eliza, this letter is powerful evidence, but using it means exposing everything. Your relationship, your children, the intimacy of what existed between you and Mr. Thornton. The Thornon family will argue you seduced him, manipulated him.

They’ll say terrible things about you in open court.” “Are you prepared for that?” Eliza thought about Marcus, Sarah, and Thomas, about the children growing up in the in between space between slavery and freedom, between black and white, between legitimate and illegitimate, about the future she could give them if she won this fight, and the future they’d have if she surrendered. I’ve been called terrible things my entire life. Mr.

Whitfield, what’s a few more insults compared to my children’s freedom? But she had no idea what was actually coming because the Thornton family wasn’t just going to insult her. They were going to try to destroy her. And they were going to use every weapon Antibbellum Mississippi society had to offer.

Weapons forged in generations of slavery, rape, denial, and the desperate need to maintain a social order that required some people to be human and others to be property. The first hearing was scheduled for August 1854. Both sides would present their arguments about whether the will should be probated at all. Judge Foster’s courtroom was packed with every prominent citizen in Nachez. People stood in the back, crowded the aisles.

This wasn’t just a legal proceeding. It was a public spectacle. Margaret attended, dressed in her morning clothes, her children beside her. She’d made sure Elizabeth and Anne looked pale and fragile, perfect victims of their father’s betrayal. Robert Jr. sat stone-faced, radiating barely controlled anger. The message was clear.

Respectable white family destroyed by enslaved seductress. Eliza sat on the opposite side of the courtroom with Whitfield. She’d worn her plainest dress, no jewelry, hair pulled back severely. She’d been advised to look humble, non-threatening. To perform deference, even while fighting for millions of dollars.

The performance required of both women in that courtroom said everything about the roles they were trapped in. Margaret had to perform wounded dignity. Eliza had to perform Grateful Humility. Both performances were lies, and everyone watching knew it. Thomas Thornton opened with a speech that would be reported in newspapers across the South.

Your honor, this case is not merely about one man’s will. It’s about whether the foundations of our society can withstand attacks from those who would pervert natural law. My brother, in his final illness, was corrupted by a woman who used her position in his household to extract an unnatural influence. She bore his children, a crime against both his marriage and moral order. And now she seeks to profit from her own wrongdoing. Whitfield stood to respond.

He was older than Thomas Grayer, with a reputation for careful, methodical argument. Your honor, the question before this court is simple. Did Robert Thornton have the legal right to dispose of his property as he chose? Mr. Thomas Thornton argues his brother was incompetent.

I have three physicians prepared to testify that Robert Thornton was of sound mind until hours before his death. He argues undue influence. I have Robert’s own letter explaining his reasoning in detail. He argues Mississippi law forbids this transfer. I have trust structures specifically designed to comply with every statute.

Judge Foster listened to both sides, asked a few questions, then made a ruling that surprised everyone. This case raises complex legal questions that cannot be resolved in a preliminary hearing. I’m ordering full probate proceedings. Both sides will have the opportunity to present witnesses, evidence, and expert testimony. We will examine Mr.

Thornton’s mental state, the validity of his relationship with Miss Eliza, the legitimacy of the trust structures, and whether Mississippi law permits what this will attempt to do. He banged his gavvel. Court will reconvene in October for full proceedings. It was a victory for Eliza of sorts. The judge hadn’t immediately dismissed the will, but it was also the beginning of something that would consume years of her life.

As people filed out of the courtroom, Margaret and Eliza passed each other in the aisle. Margaret stopped, looked at Eliza directly for the first time since the parlor scene. When she spoke, her voice was low enough that only Eliza could hear. You think you’ve won something, but all you’ve done is guarantee that everyone will know exactly what you are.

And when this is over, when you’ve been humiliated in public and exposed as a scheming you’ll wish you’d taken the dollar and disappeared. Eliza met her eyes. When this is over, Mrs. Thornton, your children will still have their name, their skin, and their place in society. Mine will have their freedom. I’ll take that trade. They would never speak directly again. But the battle between them was just beginning.

Between August and October 1854, Nachez society divided into camps with the precision of a military deployment. On one side stood the Thornton family and their allies, old money families who saw the will as an existential threat to everything they’d built their world upon.

On the other side stood a much smaller, much quieter group, a handful of abolition sympathetic merchants, several Quaker families, and a few people who simply believed a man should be able to dispose of his property as he wished, regardless of who benefited. But most people fell into a third category, those who watched with horrified fascination, unable to look away from a scandal that forced them to confront questions they’d spent lifetimes avoiding.

Because Robert Thornton’s will hadn’t just exposed one family’s secrets. It had ripped open a wound that ran through every plantation, every fine house, every respectable family in the South. The unspoken arrangements, the children who existed in legal limbo, the women who occupied spaces between property and person, between servant and something else entirely.

Eliza discovered just how deep that wound ran when she tried to buy supplies and Natches. She’d gone to Henderson’s general store, a place where Belmont had held accounts for 20 years. She needed fabric, lamp oil, basic household goods. She handed her list to Thomas Henderson, who’d always been polite when she’d come in with orders from Margaret.

Henderson looked at the list, then at Eliza, then back at the list. I’m sorry, but I can’t extend credit to you. The Belmont account is closed. Mrs. Margaret Thornton closed it last week. He wouldn’t meet her eyes. And even if it weren’t Miss Eliza, I can’t do business with you. I’m sorry. I truly am. But my other customers have made it clear they won’t shop here if I serve you. Eliza felt the stairs of the other people in the store.

All white, all watching to see what she’d do. I can pay cash. It’s not about payment. It’s about Henderson trailed off, looking miserable. My family’s reputation. I have daughters to marry off. I can’t be seen as supporting what you’re doing, what she was doing, as if she’d engineered this, as if she’d written the will herself. Eliza left without the supplies. She tried two more stores.

Same result. Word had spread with the efficiency of a plague. Anyone who helped Eliza would be socially destroyed. The white establishment of Nachez had closed ranks. That evening, a delegation of three women appeared at Belmont. Not the main house. They wouldn’t go there. They came to the kitchen house where Eliza was supervising dinner preparation.

These were women of color, free women who’d built lives in Nachez’s small free black community. Joanna Price, the oldest, spoke first. Miss Eliza, we heard what happened in town today. We wanted you to know we have a network. Merchants who will deal with us quietly. Suppliers who will deliver to the back door after dark. You’re not alone in this.

Eliza felt something crack in her chest. For weeks, she’d been so focused on the legal battle that she hadn’t let herself feel how isolated she’d become. “Why would you help me?” “You don’t know me. We know what you are,” Joanna said quietly.

“You’re a woman who got free through circumstances most of us can’t imagine. And now you’re fighting to stay free while every white person in Nachez tries to push you back into bondage. If you lose this fight, it’s not just you who loses, it’s every one of us. Because what you’re proving is that we can’t be trusted with freedom. that we can’t manage property, that we’re not fully human.

So, yes, we’re going to help you because your battle is our battle.” It was the first moment Eliza had allowed herself to understand what she actually represented. Not just one woman fighting for an inheritance, but a test case for whether someone like her could exist as a free property owner in Mississippi.

And if she failed, it would justify every law that restricted free black people’s rights, every argument that they couldn’t handle freedom, every rationale for keeping slavery intact. The weight of it was crushing. The full trial began on October 15th, 1854. Judge Foster’s courtroom was even more packed than it had been in August. Thomas Thornton had assembled an impressive legal team, three attorneys, all from prominent families.

They’d spent months preparing, interviewing every person who’d ever worked at Belmont, building their case. Their strategy was brilliantly cruel. They weren’t just attacking the will. They were attacking Eliza herself, destroying her character so thoroughly that no judge could possibly rule in her favor. The first witness they called was Margaret Thornton.

Margaret took the stand, wearing black silk, looking every inch the grieving widow. Thomas Thornton, conducting the examination himself, began gently. Mrs. Thornton, how long were you married to Robert? 23 years. Her voice trembled perfectly. And in that time, did you manage his household faithfully? I did everything a wife should do. I bore him four children.

I maintained his home. I supported his business endeavors. I honored my marriage vows. Even when? She stopped, dabbed her eyes with a handkerchief. Even when? What? Mrs. Thornton. Even when I discovered he’d betrayed those vows with her. Margaret’s finger pointed directly at Eliza. Whitfield stood. Objection. This testimony is prejuditial and irrelevant to overruled. Judge Foster said the witness may continue.

Margaret’s testimony was devastating because it was largely true. She described discovering Robert’s relationship with Eliza in 1845 after Marcus was born. She described confronting Robert, who’d admitted the affair but refused to send Eliza away. She described years of humiliation watching her husband’s mistress live in her house, raise his illegitimate children under her own roof.

Did you ever consider leaving your husband? Thomas asked, “Where would I go?” “A woman can’t simply leave her marriage because she’s unhappy. I had children to think of, a reputation to protect. I did what any Christian woman would do. I forgave him. I prayed for him. I hoped he would see reason and end the relationship.

Instead, he continued it for 13 years and then he died and left me with nothing. She broke down crying. It was a masterful performance and it was working. Eliza could see it in the faces of the jury. 12 white men, all property owners, many of them married. They looked at Margaret with sympathy. They looked at Eliza with disgust. When Whitfield cross-examined, he was gentle but firm. Mrs.

Thornton, you testified that you confronted your husband in 1845. What exactly did he say? He said it was none of my concern. Those were his words. None of your concern. Margaret hesitated. He said he said his relationship with Eliza was his private business. Did he ever promise to end the relationship? No.

Did he ever apologize for it? No. In fact, didn’t he tell you explicitly that he would continue the relationship and you would have to accept it? Margaret’s face hardened. “Yes, and you did accept it, didn’t you? For 13 years, you accepted it. You remained in the marriage. You continued to benefit from the plantation’s income.

You attended social functions with your husband. To the outside world, you maintained the fiction that everything was fine. I had no choice. You had the same choices Eliza had,” Whitfield said quietly. “The difference is you could have left. She couldn’t.

You chose to stay because the benefits outweighed the humiliation. Eliza stayed because she was property. Objection. Thomas was on his feet. Council is badgering the witness. Sustained. Mr. Whitfield. Move on. But the point had been made. Margaret had stayed in a marriage she knew was broken because divorce would have destroyed her socially and financially.

She chosen respectability over dignity. That didn’t make her the villain. It made her a victim of the same system that enslaved Eliza. But it also meant her moral high ground was shakier than she wanted to admit. The next several days of testimony were brutal. The Thorntons called servant after servant, asking them to describe Eliza’s position in the household.

What emerged was a picture of a woman who’d held unusual power for someone enslaved, managing accounts, making decisions, having private conversations with Robert that excluded even his wife. But Whitfield’s cross-examinations revealed something else. Respect. Almost every servant, when pressed, admitted that Eliza had been fair, kind, even that she’d helped people, protected them from worse overseers, used her influence with Robert to prevent families from being separated.

One woman, an elderly cook named Aunt Ruth, gave testimony that stopped the courtroom cold. She’d worked at Belmont for 30 years and had known everyone involved. Thomas Thornon asked her, “Did you observe the relationship between Miss Eliza and Mr. Robert? I saw what there was to see.

Did it seem to you that she had manipulated him, controlled him? Aunt Ruth looked at Thomas Thornton with eyes that had seen too much of life to be intimidated by a white lawyer. Mr. Thomas, you asking me if a woman who was property manipulated the man who owned her? That don’t even make sense.

How’s someone with no power supposed to manipulate someone with all the power? She bore his children, used them to She bore his children because he came to her room and she couldn’t say no. That ain’t manipulation. That’s what happens when one person owns another person. Your brother wasn’t manipulated. He just finally admitted what he’d been doing. Thomas tried to recover. But she must have used those children to extract sympathy, too.

Those children looked just like your brother, Mr. Thomas. Everyone could see it. Everyone knew. The only person pretending not to know was Miss Margaret. And even she knew. She just couldn’t say it out loud because saying it would mean admitting her husband preferred someone else. The problem wasn’t that Miss Eliza manipulated anyone. The problem is that Mr. Robert told the truth about something everyone wanted kept secret.

It was the most honest testimony the court had heard. And Thomas Thornon quickly dismissed the witness, realizing she was doing more harm than good to his case. But the Thornton had one more weapon, and it was the most devastating one of all. They called Dr. Samuel Morrison, the physician who’ treated Robert in his final months.

Morrison was elderly, distinguished, and highly respected in Natchez. His testimony was crucial because it addressed Robert’s mental state. Dr. Morrison, Thomas began, you treated my brother during his final illness. What was his condition? Mr. Thornton suffered from consumption of the lungs. The disease had progressed significantly by early 1854.

He experienced fever, night sweats, severe coughing, and increasing weakness. Did this illness affect his mental capacity? Morrison hesitated. Consumption can affect the mind, particularly in its advanced stages. Fever can cause delirium. The physical suffering can lead to despair, irrationality. In your professional opinion, was my brother capable of sound judgment in the weeks before his death.

And here Morrison looked genuinely troubled. I believe he was physically suffering so much that his judgment may have been impaired. Yes. Whitfield’s cross-examination was critical. Dr. Morrison, you say, may have been impaired. Were you present when Mr. Thornton dictated his will to Mr. Whitfield? No. Did you examine him that specific day? No.

Did he ever, in your presence, say anything that suggested he was confused about his affairs, unable to recognize people, or otherwise mentally incompetent? Morrison shook his head slowly. No, Robert was always lucid when I saw him. He spoke clearly about his condition. He understood he was dying. He made rational decisions about his care. So, your testimony about impaired judgment is speculation. It’s based on my medical understanding of his condition.

But you have no direct evidence that Robert Thornton was mentally incompetent when he dictated his will. No, Morrison admitted. I don’t. The testimony went back and forth for days. Witnesses for both sides. character assassinations and defenses, financial experts arguing about whether the trust structures were legal.

Every intimate detail of Robert and Eliza’s relationship dragged into public view. And through it all, Eliza sat in that courtroom, forced to listen as people debated whether she was human enough to own property, whether she’d seduced or been raped, whether her children deserved freedom or should remain enslaved.

The psychological toll was immense. At night back at Belmont, Eliza would sit with Marcus, Sarah, and Thomas, trying to maintain normaly while their entire world hung in the balance. Marcus, now 10, was old enough to understand some of what was happening.

He’d ask questions Eliza couldn’t answer, “Mama, why do they hate you so much? They don’t hate me, baby. They hate what I represent. What do you represent?” How could she explain to a 10-year-old that she represented the lie at the heart of southern society? that she was proof that the children of enslaved women and white men were human beings who deserved rights, that she threatened the entire social order that said some people were property and others were people. She couldn’t.

So, she just held him and said, “I represent hope that things can be different.” But the person who provided the most crucial testimony wasn’t a character witness or a medical expert. It was James Whitfield himself, Robert’s attorney, who drafted the will and heard Robert’s reasoning firsthand.

Whitfield took the stand in early November, and his testimony would change everything. Thomas Thornton tried to discredit him. Mr. Whitfield, isn’t it true that you stand to earn substantial fees if this will is probated? I’m being compensated for my legal services. Yes.

So, you have a financial incentive to defend this will regardless of its validity? I have a professional obligation to defend my client’s wishes. Robert Thornton came to me 6 weeks before his death and dictated this will over the course of two full days. He was more lucid, more purposeful than many clients I’ve worked with. He knew exactly what he was doing. What exactly did my brother say when he came to you? Whitfield pulled out his notes.

He said, “I’m dying, James. I’ve made many mistakes in my life, but I have a chance to correct one of them. I want to free Eliza and provide for our children. I know this will destroy my relationship with my legitimate family. I know it will cause a scandal, but I would rather die honestly than live one more day lying to myself.

The courtroom went silent. He said more. Whitfield continued. He said, “Margaret will never forgive me. My children will hate my memory. Nachez society will condemn me. I accept all of that because the alternative is dying knowing that I enslaved my own children, that I kept the woman I loved in bondage and that I was too much of a coward to face the truth.

I’ve been a coward my whole life, James, let me at least die brave. Thomas Thornton’s face had gone pale. These were his brother’s words documented in Whitfield’s notes, impossible to deny, but Thomas tried. My brother was clearly not in his right mind if he said such things. The Robert Thornton I knew would never, the Robert Thornton you knew, Whitfield interrupted, was the performance he gave for Nachez society.

The Robert Thornton who dictated this will was the man beneath that performance, and he was exhausted from maintaining the lie. It was the turning point of the trial. Whitfield’s testimony, backed by detailed notes and the letter Robert had written, made it impossible to dismiss the will as the product of a confused mind.

Robert had known exactly what he was doing. He’d understood the consequences and he’d done it anyway. Judge Foster called for a recess after Whitfield’s testimony. When court reconvened a week later, he looked weary. This case had taken its toll on everyone involved. The final arguments took an entire day.

Thomas Thornton argued passionately that the will violated Mississippi law, public policy, and moral order. Whitfield argued that Robert Thornton had every legal right to dispose of his property as he chose and that the trust structures complied with all relevant statutes. Then Judge Foster asked the question that cut to the heart of everything. Mr.

Whitfield, are you truly arguing that Mississippi law should permit a negro woman to own a plantation with enslaved workers to control business interests to exercise the kind of economic power that has always been reserved for white men? And Whitfield, in what would become his most famous legal argument, responded, “Your honor, I’m arguing that Mississippi law already permits free people of color to own property.

The legislature has restricted those rights, yes, but not eliminated them. More importantly, I’m arguing that if a white man of property has the legal right to manummit enslaved people he owns and provide for them, then Robert Thornton has exercised that right. The fact that he chose to provide generously rather than minimally doesn’t make his actions illegal.

It just makes them unusual. But surely the magnitude of this bequest is beyond what the law contemplated. With respect, your honor, the law doesn’t specify how much a freed person can inherit. It simply restricts their rights once they’ve inherited. Miss Eliza, if she receives this property, will still face all the legal restrictions that free people of color face in Mississippi. She won’t be able to vote. testify in court against whites or exercise many other rights.

But owning property, the law permits that. And if we’re going to say the law has a secret cap on how much property a freed person can own, then we’re inventing restrictions that don’t exist in statute. Judge Foster sat back in his chair. Everyone in the courtroom knew what he was thinking.

This wasn’t just a legal decision. It was a social one. Rule for Eliza. and he’d be saying that Mississippi law permitted a formerly enslaved black woman to become one of the wealthiest people in the state. Rule against her and he’d have to invent legal reasoning that didn’t quite exist in the statutes.

I’ll issue my ruling in 30 days, he said finally. And then everyone waited. Those 30 days felt like 30 years at Belmont. An uneasy truce had settled over the plantation. Margaret remained in the main house occupying the east wing. Eliza stayed in her quarters behind the kitchen, though legally she now had the right to occupy any part of the property. Neither woman crossed into the other’s space.

They existed in parallel universes within the same walls, each pretending the other didn’t exist, but the enslaved people at Belmont existed in a strange limbo that was even more unsettling. They didn’t know who owned them anymore. Was it Margaret as the widow? Was it Eliza, according to the contested will, or were they about to be sold to settle debts if the whole estate collapsed under the weight of legal fees? A man named Samuel, who’d worked the fields at Belmont for 15 years, later described the psychological torment. We didn’t know if we should pray for Miss Eliza to win or lose. If she won, we’d be owned by a woman who’d been enslaved herself just months before. If she lost, we’d probably be sold off to pay the lawyers. Either way, our lives weren’t our own. But at least Miss Eliza knew what it felt like. That counted for something. In Nachez, the case had consumed every conversation.

Dinner parties debated the legal arguments. Church groups discussed the moral implications. The local newspaper ran daily updates. People placed bets on the outcome. The case had stopped being about one family and become about the entire social structure of the South. And beneath all the public debate ran a current of fear. Because if Eliza won, what did that mean for every other white man who’d fathered children with enslaved women? Could they follow Robert Thornton’s example? Would there be a wave of deathbed confessions? Wills that legitimized hidden families?

Legal transfers that upended the racial hierarchy? The establishment had to stop this, not just for the Thornon family, but for everyone with secrets to protect. On December 12th, 1854, Judge Foster issued his ruling. The courtroom was packed beyond capacity.

People stood in the hallways, crowded around the windows, desperate to hear the verdict that would define Mississippi law for years to come. Judge Foster looked exhausted. He’d aged visibly in the month since the trial began. When he spoke, his voice carried the weight of a man who knew his decision would satisfy no one.

I have spent these 30 days in careful consideration of the law, the evidence, and the principles at stake in this case. What I’m about to say will disappoint both parties. but it represents my best understanding of justice within the constraints of Mississippi law. Eliza felt her heart hammering. Beside her, Whitfield sat perfectly still. First, regarding Mr. Robert Thornton’s mental capacity. I find that the evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that Mr.

Thornton was of sound mind when he dictated his will. Dr. Morrison’s testimony about potential impairment was speculative. Mr. Whitfields. Detailed notes demonstrate a man who understood his actions and their consequences. This will was not the product of delirium or diminished capacity. Margaret made a small sound of distress.

Her attorney gripped her arm. Second, regarding undue influence. I find no evidence that Miss Eliza coerced or manipulated Mr. Thornton. The relationship between them, while morally troubling to many, does not constitute legal undue influence. Mr. Thornton made his choices freely as evidenced by his letter and testimony from multiple witnesses. Thomas Thornton’s face darkened.

He could see where this was heading. However, Judge Foster continued, and that single word made everyone in the courtroom tense. I must address the fundamental legal question. Can Mississippi law permit what this will attempt to do? He paused, looking directly at Eliza.

Miss Eliza, under the terms of this will, would become one of the largest property owners in Adams County. She would control enslaved workers. She would manage business interests. She would exercise economic power that has traditionally been reserved for white male citizens. The question is not whether Mr. Thornton had the right to free you. He did.

The question is whether he had the right to transfer this magnitude of property to a freed person of color. And on this point, I find that Mississippi law is ambiguous. The statutes restrict the rights of free people of color, but they do not explicitly forbid property ownership or inheritance. Whitfield leaned forward. This was better than he’d hoped. Therefore, I am ruling that Robert Thornton’s will is valid and should be probated with modifications.

The courtroom erupted. Judge Foster’s gavel cracked like gunfire. Order. I will have order. When the room quieted, he continued, “Miss Eliza shall receive her freedom as stipulated in the will. She shall receive custody of her three children, Marcus, Sarah, and Thomas, who shall also be freed.

These provisions are unambiguous and legal.” Eliza felt tears running down her face. “Her children, they were free. Whatever else happened that was permanent, however,” Foster said, and his voice grew heavier, “I cannot allow the transfer of the entire estate as written.

Such a transfer would violate the Spirit of Mississippi law regarding property ownership by freed people of color, even if it doesn’t violate the letter. Therefore, I am ordering the following distribution. He read from his written ruling. Miss Eliza shall receive Belmont Plantation’s North Tract, approximately 800 acres, along with the buildings thereon.

She shall receive $50,000 in liquid assets to be held in trust and administered by a white guardian appointed by this court. She shall receive her personal effects and those of her children. $50,000 was substantial. 800 acres was a fortune, but it was a fraction of what Robert’s will had specified. The remainder of the estate, the south tract of Belmont, the Natchez properties, the business interests, and additional liquid assets shall be divided among Robert Thornton’s legitimate heirs, his widow Margaret, and their four children, in proportions determined by standard inheritance law. Margaret gasped. It wasn’t everything, but it was something. Her children would have inheritances. She would have property. Furthermore, Judge Foster continued, “I am ordering that the enslaved workers at Belmont be divided between the two estates. Miss Eliza shall not own enslaved people.

The court finds this morally unconscionable given her recent status. Those workers shall be transferred to the Thornon family estate or sold with proceeds divided appropriately.” Eliza felt the decision like a physical blow.

She’d won her freedom and her children’s freedom, but the people she’d lived beside for 11 years would remain enslaved. She’d fought so hard and still the fundamental injustice continued. This ruling, Foster concluded, attempts to honor Robert Thornton’s intentions while respecting the legal and social realities of Mississippi. Both parties have 30 days to appeal to the state supreme court if they choose. He banged his gavvel. This court is adjourned.

The courtroom exploded into chaos. Reporters rushed out to file stories. Spectators argued loudly about whether the ruling was just. Margaret’s family surrounded her, debating whether to appeal, and Eliza sat very still, trying to understand what she’d just won and lost simultaneously. Whitfield turned to her. Miss Eliza, this is a victory. You’re free.

Your children are free. You have property and money. We can appeal for more, but but every day we spend appealing is another day my children live in uncertainty,” Eliza said quietly. “And every day Margaret Thornton spends fighting us is another day she can’t rebuild her life.” “This needs to end.

Are you saying you’ll accept this ruling?” Eliza thought about Marcus, Sarah, and Thomas. About the 800 acres that would be theirs. about the $50,000 that could educate them, establish them, give them futures she’d never imagined possible, about the cost of continuing this battle, not in money, but in humanity. Yes, she said. I’ll accept it. On the other side of the courtroom, Margaret was having a similar conversation with her attorneys.

Thomas Thornton wanted to appeal to fight for the full estate, but Margaret, looking across the room at Eliza, seemed to have reached some internal conclusion. No, she said. No more. We have enough to rebuild. My children have inheritances. I have property. And I am so tired of fighting over Robert’s corpse. Her voice broke on the last words. Because that’s what this had all been. A battle over a dead man’s legacy.

A fight about who he’d loved more, who deserved what, who would carry his memory forward. The two families left the courtroom separately. They would never speak again, but they would remain connected forever by the man who’d loved them both. in different ways and who destroyed them both trying to make amends for crimes he couldn’t undo.

The property division took three months to finalize. In March 1855, Eliza took possession of her 800 acres, the north tract of Belmont, with its own main house, smaller than the original but substantial. The trust fund was established with a banker named Harrison Wells serving as guardian.

Wells was one of the few Nachez businessmen who’d agreed to work with Eliza, partly from principal, partly from the profit opportunity. Margaret and her children took the South Tract and the Natchez properties. The cotton factoring business was sold with proceeds divided. The enslaved workers were divided by lot, a process that separated families and destroyed lives.

Just as it always did, Samuel, the field worker who’d spoken about the psychological torment, was sold to a Louisiana planter. He would eventually escape during the Civil War and make his way north. In a memoir written years later, he described watching Eliza on the day of the division. She was crying while they split us up.

Crying like her heart was breaking, and I thought, “She knows. She knows exactly what this feels like. She just doesn’t have the power to stop it. That’s what freedom meant for her. She could save her own children, but not anybody else’s. I’ve spent years trying to decide if I forgive her for that. I still don’t know. Eliza moved into her new house with Marcus, Sarah, and Thomas in April 1855.

For the first time in her life, she owned the space she lived in. For the first time, her children slept in beds that belonged to them. For the first time, they could read books openly, play freely, exist without constantly performing subordination. But the freedom was complicated. Natcha society never accepted Eliza. White merchants still refused to deal with her directly.

She had to conduct all business through Harrison Wells or other intermediaries. Her children were educated at home because no school would take them. Too black for white schools, too wealthy for the colored school, too ambiguous to fit anywhere. The isolation was profound.

The free black community that had supported Eliza during the trial remained friendly, but she existed in a strange social space between worlds. Too elevated by wealth and property ownership to fit comfortably with others of her race, too marked by her skin and history to ever be accepted by whites. Marcus, as he grew older, became increasingly bitter about this isolation. On his 16th birthday in 1861, he asked his mother why they didn’t leave Mississippi. go north where their money could buy them genuine freedom.

Eliza looked at the land she’d fought so hard to claim. Your father gave us this. It’s yours. If we leave, we’re saying they won. That we don’t deserve to be here. Don’t belong here. I won’t give them that satisfaction. But history would make the decision for her. The Civil War began 3 months later. Mississippi secceeded. Belmont Plantation, both North and South tracks, struggled as the economy collapsed.

By 1863, Union forces controlled Nachez. The enslaved people at the Thornon tract fled to Union lines, leaving Margaret with land she couldn’t work. Eliza’s tract, having fewer workers and more liquid assets, survived slightly better, but barely.

In 1864, Marcus enlisted with the Union Army, one of thousands of black men who fought for the freedom his mother had achieved through a white man’s guilt. He survived the war and returned to Belmont in 1866, wearing a Union uniform to the land his father had left him. Margaret saw him return. She was 63 by then, widowed twice.

She’d remarried briefly in 1860, but her second husband had died at Vixsburg. She watched Marcus ride up the road in his blue uniform, a free black man who’d fought to destroy the world she’d grown up in, and she felt nothing but exhaustion. They passed each other on the road between the north and south tracks one day in 1867. Both were older, weathered by war and loss.

Marcus tipped his hat to her, a gesture of respect he didn’t owe. Margaret nodded back. They didn’t speak. There was nothing left to say. Margaret died in 1871 in the house she’d fought so hard to keep. Her children inherited what remained of the South Tract, but the plantation economy was dead.

They sold the property within 5 years and scattered Robert Jr. to Texas, Elizabeth to Charleston, Anne to Mobile, William to New Orleans. None of them ever returned to Nachez. Eliza lived until 1889. She saw her children grow, marry, have children of their own. Marcus became a teacher, educated freed people during reconstruction. Sarah married a minister and moved to Philadelphia.

Thomas studied law in Ohio and became one of the first black attorneys in the north. She died owning the land Robert Thornton had given her, though by then it was worth a fraction of its antibbellum value. Her will divided the property among her three children and her seven grandchildren.

A black family owning 800 acres in Mississippi, an impossibility before the war, a fragile reality afterward. But here’s what the history books don’t tell you. Here’s the part that makes this story more than just a legal curiosity. After Eliza died, her children found a box in her room. Inside were letters, dozens of them.

Letters Robert had written to Eliza over the years, hidden away, never shown to anyone. Letters that revealed a man tortured by the contradictions of his life. A man who loved someone he’d enslaved and couldn’t reconcile that impossibility. a man who knew he was committing evil while convincing himself he was being kind.

One letter written in 1850 read, “Eliza, I tell myself that what we have is love. That because I care for you, because I value you, because I plan to free you someday, our relationship is different from what other men have with their slaves. But late at night, when I’m honest with myself, I know the truth. You can’t refuse me. You can’t leave. You can’t even tell me what you really think without risking punishment.

How can anything built on such foundations be love? And yet, I can’t stop coming to you. I’m addicted to the fantasy that you want me, even though I know you can’t freely want anyone who owns you. I’m a monster pretending to be a man. And the worst part is that I’ll keep being a monster because the alternative is admitting what I’ve done to you. And I’m too much of a coward for that.

Another letter from 1853. I’ve decided to change my will to give you and our children everything. Margaret will hate me for it. My legitimate children will curse my memory. But I need to believe that one act of honesty can redeem a lifetime of lies.

I need to believe that freeing you, providing for you makes up for enslaving you in the first place. I know it doesn’t. I know there’s no redemption for what I’ve done, but I have to try. Even if it destroys everyone I love in the process. Those letters reveal the truth that the trial never addressed. Robert Thornton’s will wasn’t an act of love. It was an act of confession, a desperate attempt by a dying man to acknowledge his crimes and pretend that acknowledgement was the same as absolution. He freed Eliza and their children, not because it was right, but because he couldn’t face dying with the lie intact. He gave them property not as a gift, but as payment for what he’d stolen, their freedom, their autonomy, their humanity. And in doing so, he forced everyone around him to confront truths they’d spent lifetimes denying. But here’s the question that haunts this story. Did it matter? Did Robert Thornton’s final act change anything? His legitimate children were emotionally destroyed.

His widow spent years fighting over scraps of what she’d thought was hers. Eliza won property but lost the community of enslaved people she’d lived among. The enslaved workers at Belmont were sold and scattered, their families destroyed by the property division and Mississippi law.

The ruling in Eliza’s case didn’t change the fundamental structures of slavery. It didn’t prevent other families from keeping their mixed race children enslaved. It didn’t challenge the system that made cases like this possible. If anything, it reinforced it by allowing just enough exception to prove that the system was fair while changing nothing about its fundamental brutality.

So, what does this story mean? What are we supposed to learn from a plantation master who left his fortune to a woman he’d enslaved and in doing so destroyed two families in the name of redemption he never really achieved. Maybe the lesson is this. There are some crimes you can’t make amends for. some wrongs that can’t be writed by good intentions or deathbed confessions. Robert Thornton spent 13 years committing daily violations against Eliza’s humanity, against his own children’s freedom, against every principle he claimed to believe in. And then he tried to fix it all with a legal document. But you can’t uninslave someone. You can’t give back the years you stole. You can’t undo the trauma of being property, of raising your children as property, of living every day in a situation where your body, your will, your very self belongs to someone else. Freedom given as a gift from an owner isn’t the same as freedom claimed as a right.

Property inherited through a will isn’t the same as property earned through your own labor. And a deathbed confession doesn’t absolve a lifetime of choosing comfort over courage. The case of Robert Thornton and Eliza Marie forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth. The antibbellum South wasn’t just a system of obvious villains and innocent victims.

It was a system that corrupted everyone it touched. Masters who convinced themselves they were benevolent. Wives who pretended not to see. Children raised to accept brutality as normal. And enslaved people forced to survive by whatever means available, even if that meant collaborating with their own oppression.

Robert Thornton’s will didn’t fix that system. It just revealed how completely broken it was. And maybe that’s the real legacy of this case. Not that one man tried to do right at the end of his life, but that the system he lived in made doing right impossible. You couldn’t be a good person and a slaveholder. You couldn’t love someone and own them.

You couldn’t build a fortune on stolen labor and stolen lives and then pretend a generous inheritance made up for it. Robert Thornton died trying to believe he could. Eliza lived knowing he couldn’t. Margaret spent years fighting over the remains of a lie. And their children, all of them, legitimate and illegitimate, white and black, paid the price for trying to exist in a world built on contradictions that couldn’t be sustained. The north tract of Belmont still exists.

It’s private property now, owned by descendants of Eliza and Robert through Marcus’s line. The main house has been restored. It’s beautiful, like something out of a plantation fantasy. All white columns and sweeping porches. But if you visit, if you stand in that house where Eliza once lived, you can still feel the weight of all the impossible choices that were made there.

All the people who tried to be good within a system designed to make goodness impossible. All the lives destroyed by people who thought they were being kind. The sealed room has brought you this story because it matters. Because these contradictions, these attempts to redeem irredeemable wrongs, these systems that corrupted everyone they touched, they didn’t end with slavery. The patterns persist. The excuses evolve.

The fundamental question remains. Can you make amends for participating in evil? Or are some prices too high to ever be paid? What do you think? Was Robert Thornton’s will an act of courage or cowardice? Was Eliza’s acceptance of the judge’s compromise pragmatic or a betrayal of those left enslaved? Could any decision made within that system be called just? Share your thoughts in the comments. These aren’t easy questions and they don’t have comfortable answers.

And if this story made you think, made you uncomfortable, made you question the simple narratives we tell ourselves about history, then subscribe, hit that notification bell, because history isn’t just dates and dead people. It’s about understanding how we got here, what we inherited, and what we’re still trying to make, right? The past isn’t past.

It’s just waiting for us to be brave enough to look at it honestly. And sometimes the most terrifying stories are the ones where everyone involved thought they were doing the right thing.

News

9 Nuns Missing During a Pilgrimage in 2001 – 24 Years Later, A Diary Underground Exposes a Horrific Crime

9 Nuns Missing During a Pilgrimage in 2001 – 24 Years Later, A Diary Underground Exposes a Horrific Crime In…

A Family of 4 “Vanished” Without a Trace – 3 Years Later, A Discovery 100 Miles Away Exposed the Killer

A Family of 4 “Vanished” Without a Trace – 3 Years Later, A Discovery 100 Miles Away Exposed the Killer…

Two Priests Disappeared in 2009 — 15 Years Later, The Truth Is Revealed, Shocking Everyone

Two Priests Disappeared in 2009 — 15 Years Later, The Truth Is Revealed, Shocking Everyone One night in May 2009,…

Four Nuns Missing in 1980 – 28 Years Later, A Priest Finds Life Underground

Four Nuns Missing in 1980 – 28 Years Later, A Priest Finds Life Underground In 1980, four nuns living in…

“The Thorn Sisters — The Night the Frontier Fought Back”

“The Thorn Sisters — The Night the Frontier Fought Back” They came after midnight, when the wind had gone still…

(1834, Virginia) Dark History Documentary — The Sullivan Family’s Basement of 47 Chained Children

(1834, Virginia) Dark History Documentary — The Sullivan Family’s Basement of 47 Chained Children What you’re about to hear is…

End of content

No more pages to load