The Mill Creek Mother Who Closed the Windows – The Chilling 1892 Case That Shocked a Town

On the cold afternoon of February 14th, 1892, a coal merchant named Samuel Tate guided his wagon along the narrow track beside Mill Creek. The air was brittle with frost, the surface of the creek sheathed in glassy ice. He was on his last delivery of the day, a few sacks for the Witham house near the bend. Normally by this hour, he would see the children playing out front—Clara, Henry, and little Elsie, bundled in mismatched coats, their laughter carrying over the water. But that day, the yard was empty. The snow lay untouched except for Samuel’s own wheel ruts. All the shutters were closed, and not one wisp of chimney smoke marked the roof line. He knocked at the door with his gloved hand and waited.

The only sound was the slow creak of a bare branch scraping the side of the house. He tried again, harder this time, and leaned closer. That was when he caught it: an odor, faint at first, then undeniable, sweet, almost medicinal, mingled with the stale breath of air that had not moved in weeks. Samuel’s mouth went dry. He called out for Sarah, but there was no reply. By the time he climbed back onto his wagon, his mind was already turning over the oddities he had noticed in recent weeks: the uncollected mail at the general store, the shuttered windows even on mild days, and the absence of the children’s voices.

That evening, over the warmth of his own kitchen stove, he told his wife he meant to speak with Sheriff Gley in the morning. Sheriff Albert Gley, 50 years old, had spent most of his career tending to petty disputes and the occasional brawl in the saloon at the edge of town. His badge was more a tool for neighborly persuasion than for true enforcement, and he had known the Withams since before Thomas, the husband, died in the mill accident three years earlier. Sarah, he remembered, had been quiet but steady in the months after, always refusing offers of help with a polite shake of her head. He thought of her as a woman built to endure. Still, when Samuel Tate stood in his office the next morning, describing the smell and the silence, something in Gley’s gut shifted. Mill Creek was a place where you could hear a dog bark half a mile away, and for the Witham house to fall so still was not just unusual—it was unnatural.

The sheriff saddled his horse and rode out that afternoon, the ground hard beneath iron shoes, his breath clouding in the cold air. The sky hung low and colorless, the creek frozen in its meandering course. As he approached the bend, the Witham house rose out of the bare trees, its clapboard walls the gray of old bone. He noticed at once that every window was sealed, some with crossbars of nailed timber visible even from the yard. The front steps had been cleared of snow, but the porch was empty. He dismounted, boots crunching on the frozen ground, and mounted the steps. The first knock sounded too loud in the hush. No answer. The second knock was met with the faintest scuff of movement inside, as if someone had shifted their weight on the floorboards.

Then the latch turned and the door opened a narrow span. Sarah Witham stood there, her frame thin inside a high-necked dress buttoned to the throat. Her hair was pinned severely, her eyes shadowed in a way that made it hard to read them. “Sheriff,” she said, her voice flat but polite, “Is there something you need?” He explained that the neighbors had been worried, that no one had seen the children. Her gaze slid past him toward the white field beyond, as though something far away held her attention. Then she said, “They’re resting. Please don’t wake them.” The words settled in the air between them, too calm for the unease they carried. He asked if he might come inside. She stepped back without argument.

The air within was heavy, colder than it should have been, even with a fire lit in the hearth. Curtains were drawn tight. The parlor was neat to the point of vacancy: no books left out, no boots drying by the door, no scattered toys. On the dining table, four plates were laid, each empty, each clean. From the corner of his vision, he saw a narrow stair leading upward. Sarah’s eyes followed his, and she shook her head almost imperceptibly. “Let them be,” she murmured. “They’ve had enough of the world.” That was the moment when Gley understood that something was deeply wrong in the Witham house. But the shape of that wrongness, the path that had led to it, was still hidden. To uncover it, he would have to look back before the shutters, before the silence, before the winter pressed in. And that is where our story begins.

Before the Witham house became a shuttered silhouette against the winter fields, it had been a place of light. Sarah Ellen Reeves was 21 when she married Thomas Witham, a millwright at the woolen factory that stretched its long brick body along the banks of Mill Creek. Thomas was 8 years older, broad-shouldered from years of lifting and setting the heavy beams that framed the mill’s machinery. He had a calm manner, the kind of quiet patience that made him well-liked in the workshop and trusted in the town. Sarah had been raised a few miles upriver on her father’s modest farm. She was the youngest of five, the one her mother trusted with mending, with keeping the lamp chimneys clear and the cupboards neat.

Those skills served her well in the small white house Thomas rented from the mill’s owner. The front porch looked down the slope to the creek, and in the warmer months she would leave the windows open to catch the hum of water over the rocks. In the first years, the rhythm of their life was simple. Thomas rose early, walked the half mile to the factory, and returned at dusk with the smell of wool grease and sawdust clinging to him. Sarah kept the garden in straight rows, baked bread on Saturdays, and on Sundays they attended the small Methodist chapel at the bend. She joined the ladies’ sewing circle, and her laughter, though never loud, was easy then. Their first child, Clara, arrived in the summer of 1882. Two years later came Henry, and in 1887, Elsie, whose small, delighted laugh could turn heads in the pews.

The Withams were not wealthy, but they were known for the neatness of their home and the brightness of their children’s clothes. In those days, Sarah moved easily among neighbors, trading recipes, sharing garden cuttings, accepting the small loans and favors that passed quietly between young families. The change began not with tragedy, but with the slow accumulation of strain. The factory took more of Thomas’s time—extra shifts to meet quotas, repairs that kept him until after dark. Sarah managed the children alone for longer stretches, the little house seeming to shrink in winter when cold pressed at every seam.

Then, in March of 1889, the factory crane slipped while lifting a beam. Witnesses said Thomas had only a moment to shout before the timber swung wide, striking the scaffold where he stood. He fell two stories to the stone floor. The company’s foreman came to the Witham door with his hat in his hands. Sarah’s grief was quiet, controlled. She wore black, tended to the children, accepted the small compensation the mill’s owner offered, enough to pay the rent for a year and buy coal for the winter. There were casseroles left on her porch in the weeks after the funeral, and the minister’s wife visited twice. Sarah thanked her and declined.

By summer, she had decided to stay in the house. But she no longer joined the sewing circle, and her attendance at church became irregular. Some said it was the strain of raising three children alone. Others noted the look in her eyes when someone asked after Thomas, how her gaze would fix just over their shoulder. In that first year of widowhood, she kept up appearances. The children were clean, their clothes mended, the house neat, but she began to refuse invitations, preferring the company of her own walls. It was in this time, years before the shutters were nailed in place, that the pattern of retreat began, almost invisible to those who passed her.

The winter that followed would deepen that pattern, drawing her more tightly into the quiet that in time would become her only companion. Snow drifted against the clapboards, and wind found the nail holes as if the house were a musical instrument being tested for leaks. Sarah learned the sounds of the season: the small popping of a log, the soft clack of panes when the gusts changed, the dry whisper of wool. She kept the children indoors more than before, explaining that the path to the creek glazed over, that the air bit, that the wood pile must last.

At first, her choices seemed sensible. She rationed fuel, stitched quilts, and showed Clara how to dry orange peels to scent the room. But the longer the cold held, the more her world collapsed inward. She slept in snatches. She began to speak of the walls as if they were a second set of hands. “The room will keep us,” she told Henry. “The room knows what the winter takes.”

The neighbors noticed. Mrs. Penfield across the lane set stew on her porch twice. Each time by nightfall the pot was gone. By morning the towels were folded neatly on her step. There was gratitude in the gesture, but a limit too, as if thanks could be delivered without opening a door. The postmaster, Mr. Lyall, mentioned that Sarah now collected mail only on Tuesdays, and only when no one else was in the shop. The schoolteacher, Miss Baird, recorded three absences for Clara and two for Henry in a single week, then crossed them out when Sarah appeared the next day with a note about coughs.

When the new year came, the Witham house began to change its face. Curtains that once opened at morning stayed drawn. A thick shawl was tacked over the back door to keep the draft out. Cloth strips were laid along window sills. These were practical things, easily excused, but there were other changes. Sarah stopped using the mirror in the front room. Mrs. Penfield saw the mirror removed and propped like a shutter against the wall, its reflective surface turned backward. When asked about it later, Sarah answered gently, “Reflections double what we already have. We don’t need more of anything this season.”

She also began to rename the day’s routines. Bedtime became the quiet. Breakfast became the keeping. The walk to the woodpile became the careful. The children were practical about these changes; to them, the new names were a kind of game. But the habit marked a deeper shift. By late January, visits dwindled. When people from the chapel stopped by, they often found a note pinned to the front door: “Resting. Please leave any parcels at the step.” The handwriting remained firm, yet something in the spacing changed, as if she needed to slow even the shapes of her thoughts.

One Sunday, the minister’s wife sent her teenage son to carry kindling to the Withams. He returned saying he had heard a tune, faint, lilted, a lullaby, coming from upstairs, though it was midday. “Not a cheerful tune,” he said at dinner, “Just soft, like someone humming with their teeth closed.” When the thaw teased but did not arrive, the children’s friends began to report small, odd sightings. A boy named Simon swore he saw Henry standing in the front window without moving for nearly an hour, his hands at his sides, his face pale. He just watched the road, not me, Simon said. A girl from two houses over said she heard giggles from behind the hedge and found no one there.

Inside the Witham house, the days took on a structure that, to Sarah, felt like safety. She woke before dawn and warmed milk. She measured coal with a small tin cup. She taught Clara to write out sums on scrap envelopes. She read aloud from the one book she did not put away, a Bible, choosing the passages about still waters. There were good hours: Elsie’s hair drying into soft curls by the stove, Henry carving small boats. The first bottles arrived from the apothecary in this season. Laudanum appeared in many homes as winter medicine. Sarah followed directions at first, measuring drops for a rattling chest. The results were immediate and soothing: a child lulled, a room quieted, a span of hours smoothed. In the margin of an old calendar she kept, she began to note small phrases: Slept well. Afternoon gentle. Henry no cough.

She also lined the parlor rug with a second rug so footsteps would not echo. She asked the children to speak in quiet voices because sound carries differently in winter. “We let the house breathe,” she told them. “We keep it from startling.” By February, those outside the Witham door began to speak of the family in the language of weather. “Have you seen them?” became, “Are they keeping?” “Is Sarah unwell?” became, “Is she wintering hard?” Pity wrapped itself in euphemism. There were only habits and unwritten courtesies, and those tend to favor leaving people alone in their hardest hours.

One late afternoon, Miss Baird, the teacher, made her way to the house with a satchel of readers. She had told herself she would stand firm and insist on seeing the children. But when Sarah opened at her knock, the teacher faltered. The room behind her was dim, neat, and quiet in a way that felt tender. Sarah’s face was thinner, her eyes focused as if on a string stretched taut. “I brought primers,” Miss Baird said. “Clara will outpace the class if she keeps reading at home, but I’d like Henry to keep his sums.” “They’re resting,” Sarah said. “The cold makes them forget the difference between night and day. I like to give them one more hour when I can.” “Perhaps I might look in,” the teacher began. “Perhaps another day.” The refusal held a courtesy that closed like a latch. “Come when the creek runs again,” Sarah said, and smiled.

That night, the wind changed. The currents carried smells not usually noticed: the iron tang of cold water, the faint sweetness of a tonic left uncorked, the scorched wool from mittens. Mr. Tate, returning late, turned his head as he passed the Witham yard and frowned, storing the scent in memory. In the morning, Mr. Lyall stacked two letters for Sarah behind the counter and marked her name in pencil on a third. If she did not come that day, he told himself he would ask the minister to stop by again. But a customer arrived with a broken strap, and the thought drifted to the back of the mind. Before the deep freeze broke, the pattern had hardened. The Witham house was visited and not entered, spoken of and not addressed, watched and not seen.

Inside, Sarah counted the beats of the day, certain that if she could keep the world measured, it would spare the three small lives entrusted to her. The creek would eventually move again. Spring always came, but the winter had already done its work. It had taught the town how to leave her be. It had taught Sarah how to close the windows. When the first thaw finally slicked the road and the icicles loosened, a series of small events would follow, nothing spectacular, that together would show how far the season had carried them all.

The thaw came hesitantly that year. For days the snow softened only at the edges, revealing strips of sodden earth. The creek began to murmur under its ice. Sunlight returned in small rationed doses. For most households, this shift meant a stirring, but the Witham house stayed shuttered. One afternoon in early March, 10-year-old Clara was spotted by a boy named Matthew Penfield at the side of the house. He called her name once. She did not answer. He took a step closer and she turned her head in a slow, deliberate motion. “You’ll wake them,” she said. Then she stepped back until she was hidden by the wall.

Other children had their own small encounters. A girl named Ruth claimed she had been playing near the fence when she heard someone humming. She peeked through a knot hole and saw Elsie, the youngest Witham, sitting cross-legged on the ground with her eyes closed, swaying gently. She was making the same sound over and over, Ruth said later. By the time she circled to the gate, the yard was empty. The adults heard these stories with indulgent smiles, but each account left a small weight in the listener’s mind.

It was around this time that the minister’s wife, Mrs. Hammond, decided to make a visit. She knocked twice firmly. After a pause, the door opened enough for Sarah to be seen. “Spring is near,” Mrs. Hammond said. “Thought you might use this and some beans. We’ve all been through the same winter.” Sarah thanked her in a low voice and took the offerings without letting the door open wider. “The children?” Mrs. Hammond asked. “They’re resting,” Sarah replied. “It’s best to let them finish their rest.” Mrs. Hammond walked back down the lane unsettled. There was something in Sarah’s manner, something not merely sad, but enclosed.

A few days later, the first real break in the ice came. Matthew Penfield’s father noticed that one of the upstairs windows of the Witham house had been covered not with cloth, but with thin boards nailed directly into the frame from the inside. The wood was raw and fresh. He mentioned it to Samuel Tate at the post office, and Samuel nodded, saying only that he’d seen the same on the backside a week ago. “That’s not to keep weather out,” Matthew’s father said. The postmaster, Mr. Lyall, had his own quiet observation: Sarah’s Tuesday visits for mail had ceased entirely. Three letters for her now sat in a drawer, along with a package that had come from an apothecary in Reading.

One evening, as dusk slid over the fields, Henry was seen at the upstairs window by a passing farmhand. The boy was motionless, his face pale in the dim light, his gaze fixed somewhere beyond the man’s shoulder. The boards covered part of the glass, leaving a narrow gap through which Henry watched. The farmhand raised a hand in greeting. Henry did not move. The winter had trained them to keep their worries quiet. It would take one more unsettling incident to nudge anyone toward action.

It was a pale morning in early April when the incident happened. Mrs. Penfield had stepped out to sweep her porch when she noticed a small figure farther down the lane. As the shape drew closer, she saw it was Elsie Witham. The girl was barefoot, her nightdress brushing her ankles, her hair uncombed. She moved without hurry. Mrs. Penfield called to her, but Elsie did not answer, only turned her head slightly, then continued toward the bend. Alarm pricked at the edges of the older woman’s calm. She pulled on her shawl and walked quickly to catch up.

“Elsie, dear, it’s chilly. Where’s your mother?” she asked. “She’s sleeping,” Elsie said simply. Her voice was soft, almost matter-of-fact. “We have to be quiet when she’s sleeping.” Mrs. Penfield took the child’s hand. Halfway there, Elsie stopped and looked toward the field. “If we wake her, she cries,” she said. “It’s better when we don’t.” The words sat heavy between them. Mrs. Penfield kept hold of her hand until they reached the steps of the Witham house. She knocked twice. The door opened almost at once. Sarah stood there. Her eyes moved from Elsie to Mrs. Penfield without change in expression. “She knows better than to wander,” Sarah said, her tone simply flat. “Thank you for bringing her back.” She reached for the child’s hand and guided her inside. The door closed without another word. Mrs. Penfield remained on the step, unsettled by the absence of what she had expected.

That afternoon, the Penfield’s farmhand, Will, passed by the Witham house and swore later that he saw a blanket nailed across the inside of the front door. “The blanket hung heavy, blocking the thin light from the transom window. It was like they wanted to keep the day out,” he said years afterward. News of the morning’s oddness traveled quietly. But no one yet called the sheriff. Mothers were trusted to know best, and privacy was guarded more fiercely than safety. Still, for those who had noticed, the unease began to take root. The image of the youngest Witham child out on the road before breakfast lingered. Then, the shutters on the upper floor were nailed shut within the week. The pale wood of the boards caught the sunlight like a warning. No one knew it yet, but the season for asking gentle questions had ended.

By late April, Mill Creek had shrugged off most of the winter, but the Witham house remained closed to the season. Sarah no longer came to collect her mail. Mr. Lyall, the postmaster, kept her letters and packages in a tidy stack behind the counter. Among them was a parcel from a shop in Harrisburg, heavily wrapped in brown paper. Another smaller package arrived in early May from an apothecary in Reading. When the wrapping loosened slightly, the scent of cloves drifted out, mixed with something sharper, almost metallic.

The general store clerk, William Hodge, remarked to a neighbor that Sarah’s orders through the store had changed. Where she once purchased flour, sugar, and soap, she now requested items like candle molds, black fabric, spools of dark thread, and packets of dried herbs uncommon to most kitchens: Wormwood, Valerian, penny royal. The clerk packed these goods without comment, but he told his wife later that he couldn’t remember the last time Sarah had bought anything for children.

It was in the first week of May that someone from outside Mill Creek came close enough to glimpse the inside of the Witham house. A traveling salesman named George Lind had been working his way north from Lancaster, selling small mechanical coffee grinders. Late in the afternoon, looking for the quickest route to the next township, he spotted the Witham House at the bend and turned up the path. As he climbed the porch steps, he heard a sound from within, a woman’s voice, low and rhythmic, repeating a line he could not quite make out. He thought…

News

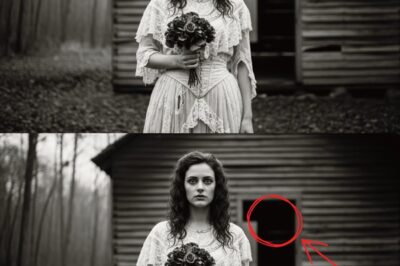

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22)

The Appalachian Bride Too Evil for History Books: Martha Dilling (Aged 22) Welcome to this journey through one of the…

The depraved rituals that Egyptian priests performed on virgins in the temple made them want to erase them from history.

The depraved rituals that Egyptian priests performed on virgins in the temple made them want to erase them from history….

The punishments in the Byzantine arenas were so brutal that even the Romans were horrified and wanted to erase them from history.

The punishments in the Byzantine arenas were so brutal that even the Romans were horrified and wanted to erase them…

What they did to Anne Boleyn before her execution was so horrific that they wanted to erase it from the historical record.

What they did to Anne Boleyn before her execution was so horrific that they wanted to erase it from the…

Pregnant at 13 With England’s Future King – The Tragic Story of Lady Margaret Beaufort

Pregnant at 13 With England’s Future King – The Tragic Story of Lady Margaret Beaufort Picture this. A girl’s scream…

How Nero Turned a Teenage Boy Into His Dead Wife

How Nero Turned a Teenage Boy Into His Dead Wife The Imperial guards found him hiding in the abandoned villa’s…

End of content

No more pages to load