The Kelleher Family’s Chilling Case: When Strangers Become Dinner

Welcome to a journey to discover one of the most chilling stories in the Ozark Mountains. Before we begin, please share in the comments where you are listening from and what time of day it is. I want to know which corners of your world these fragments of memory have reached. In 1862, while the entirety of America was engulfed in the Civil War, in the desolate Ozark mountains, another darkness appeared—not one of battles or politics, but a series of horrific crimes committed by the Keller family.

A family that seemed normal, yet they erected a private world where human beings were nothing more than a resource to be exploited. This story is reconstructed from court records, military letters, newspapers, diaries, and archaeological evidence. Some names have been changed to respect descendants, but the setting and timeline remain faithful to the truth.

And now, come with me into that journey, where we face the darkness hidden deep within human beings themselves. The year was 1862, amidst the grey rocky slopes of the Ozarks. The war roared in the distance, but its aftershocks still reverberated all the way to the dirt roads connecting Springfield to the Arkansas border. I tell this story as if sitting with you by a fire, letting the warmth chase away the chill clinging to the back of your neck. Every time I think of the Keller family—when local government was as loose as a rotting rein, courthouses burned, records scattered—people lived by instinct: hoarding salt, repairing wagons, and being wary of strangers.

Everyone told each other that while the Northerners and Southerners were shooting at each other, it was best to look after one’s own roof. But that very determination to close their doors and look out for themselves created a dark space where nameless things took root. The Keller family arrived in this region shortly before the hostilities began. Abraham Keller, a tall, gaunt man with a beard as silver as bone and eyes that always looked like they were calculating the purchase of a large plot of land along the White River. People said the price wasn’t cheap, and it was strange where the money came from.

Since the whole clan was originally from East Tennessee and had no reputation, the farm was built quickly and solidly. A two-story log house with a stone chimney, a stable big enough for eight horses, a smokehouse made of river stone, and a few small shacks arranged in an arc, as if someone had carefully drawn up the plans beforehand. Looking at it, they seemed wealthy, but hearing about them, they were silent. Edith, Abraham’s wife, was short and thin, her eyes always filled with fatigue. The sons, Tobias and Gideon, were muscular and silent as wet logs. Elias, the youngest at 17, was agile but his eyes always looked past the shoulder of the person facing him.

Miriam and Abigail, the two daughters entering adulthood, stuck to their mother wherever they went. In the early days, they appeared at the Baptist church on the hill near Forsyth (back then people called it Foright), nodded in greeting, sang softly, and then fell silent. Their names were no longer found in the activity logs. After 1850, the pastor once wrote a brief line:

“The Keller family is frequently absent; a visit is recommended.” But when the war came, who had the time to ask after anyone? People remembered Abraham for one detail: he always paid with good silver to buy salt, flour, fabric, and ammunition. No one ever saw him bring chickens, corn, or meat to the market to trade like other normal farmers. “Perhaps they have their own business,” someone said, their voice dazed with fatigue after a long journey. “Or they just prefer quiet,” another added, throwing a thin blanket over a suspicion that was beginning to stir. Yet, anyone who passed by the Keller farm shared a strange sensation: it was too quiet. No pigs squealing at feeding time, no chickens running around, no children playing in the yard; only the steady sound of an axe chopping wood and thin smoke from the chimney, like a breath deliberately kept steady to make others believe everything was normal.

The dirt road from Springfield heading South, past the steep slope and the turn into the pine forest, ran right along the edge of their land. That spring, military supply wagons passed by more frequently, as did evacuees. The stream of people on the road became dangerous. Roadblocks, interrogations, sudden changes of route. Sometimes you traveled with someone in the morning, and by the afternoon, they couldn’t keep up. By nightfall, small fires flickered like animal eyes in the forest.

Everyone wanted a roof for the night, a bowl of hot soup, a story to push back the howling wind. This region historically lived by hospitality; because it was remote, having each other was precious. But since the outposts were set up and then withdrew like the tide, since the county courthouse burned to the ground, since the police all went off to be soldiers, hospitality became something to be weighed and measured.

A stranger knocks on the door; the lights inside go out. The door opens a crack; the first question is always: “Where are you going? Where are you from? Is anyone waiting for you?” I often think, if there hadn’t been a war, the Keller family would have just been an isolated household, a bit eccentric, and would eventually become a strange anecdote told with a laugh in a tavern. But the war gave them a perfect backdrop.

Every absence could be blamed on the chaos; every faint trace was swept away by the wind and dust; every question was replaced by a bigger question. Furthermore, communication lines were broken, letters were lost, and missing persons were recorded in books with a few short words before being closed. In that darkness, a family could erect an entire private world with its own laws, as long as they kept up a sufficient appearance.

I’m not saying all the bad things were obvious from the start. The truth usually comes late, quietly, and very logically. At first, it was just the matter of Abraham often standing on the road waiting for the mail carrier. Not letting him into the yard so the dogs wouldn’t bark. Then the matter of Edith and the two daughters rarely going into town; every time they did, they walked close together as if afraid of getting lost.

There were rumors that Tobias and Gideon went out a lot at night, carrying sacks they claimed were for trapping animals. Yet no animals were ever seen, and in the morning, no one heard the sound of sharp knives butchering meat or salt being rubbed, as at the homes of skilled hunters. The scraps of history you find in church ledgers, land registries, and ink-blurred minutes at the county court are all just a hanging frame. Once the frame is hung, no one bothers to wipe the dust off.

But in the memories of those living nearby, there were short conversations sufficient to pin down a feeling. The grocery store owner said, “Abraham is polite, of few words, his eyes look like they are weighing the weight of others.” The mail carrier recounted that every time he arrived, he saw him waiting, as if he knew the arrival time in advance. A neighbor three miles away remembered, “The sound of the axe chopping is very rhythmic, not hurried, never missing a beat; it sounds like someone practicing breathing.”

I don’t believe in omens, but there are silences that explain a great deal. In that land, when cut off from the center of power, people lived by conventions: don’t ask too many questions, don’t interfere in others’ business, help each other when needed but keep a distance to avoid trouble.

That convention saved them from daily troubles, but it also gave those with evil intentions a wide cloak. Because no one was watching anyone, because everyone had more urgent matters to attend to. So, a house that was excessively quiet suddenly became logical. Everyone was tired, and fatigue is a gift to secrets during long stretches of gloomy weather. When the wind gusts through the birch trees and the rare bird calls sound like they are being strangled, you will understand why people need a story to reassure themselves.

“They are just private people.” That sentence sounds soothing, and that soothing quality has the power to lull people to sleep. I tell you this so you can see the pulse of the land at that time: slow, wary, and somewhat numb because it was forced to save its emotions for the massive losses happening elsewhere. When the heart reserves most of its space for collective anxiety, the small threads connecting neighbor to neighbor become loose.

That was all it took—just those threads loosening was enough for a family to erect a mask that fit perfectly. “We can take care of ourselves, please don’t worry.” Everyone who heard it nodded because that was the very thing they told themselves every morning. As for me, I confess: If I had lived there in the spring of 1862, perhaps I too would have walked past the wooden gate of the Keller house without turning my head.

I would have told myself, “Perhaps they have a different way of doing business.” I would have chosen to believe in the normality displayed before my eyes. Thin kitchen smoke, a clean swept yard, the rhythmic axe. We often choose to believe in things that help us keep going, especially when walking on a road full of potholes and bad news. That is how humans protect themselves. The problem is that this very method of protection inadvertently shelters things that should not be sheltered.

And so, amidst the distant roar of cannons and the murmur of the forest, a story began to take root in silence. It grew through our turning away, through ledger entries no one reread, through social greetings at the grocery store, through shiny silver coins placed on the counter without anyone asking where they came from. I tell this opening part not to criticize anyone but to acknowledge a difficult truth.

Sometimes evil doesn’t need to be noisy; it only needs an exhausted land and a community accustomed to nodding along. The Keller family found exactly such a place. And once they pulled the curtain of silence down, what happened next—as you will hear in the next part—was no longer simply the story of one household, but a crack that rippled through years and months.

To this day, recounting it, my heart still feels heavy as river stone. That spring of 1862, when the young grass had just managed to cover the Ozark slopes in a pale green, the road running through the Keller land began to see more footsteps than usual. The army passed through, lines of wagons carrying military supplies following one another. Evacuees carried their burdens from Arkansas northward seeking a bit of safety.

People walked in anxiety, amidst the sound of gunfire echoing from afar and the silence of the deep forest. No one thought that on that stretch of road, danger came not only from the enemy or bandits but from a house with blue smoke curling from its chimney. In April, the first name recorded in the missing persons book was Jonathan Myers, a 42-year-old merchant from Springfield. He left home to check his warehouse in Batesville, Arkansas, saying he would return in a week.

People waited, but day after day, there was no sign of him. A cavalry troop once met a man resembling him near the bend of the White River, right on the stretch of road next to the Keller farm, and then no one saw him again. Only much later, in a chaotic pile of items remaining at the farm, did people find a silver pocket watch engraved with the letters JM.

It was the very item his wife confirmed she had placed in her husband’s hand before his trip. The second case was not just one person, but an entire family: Samuel and Elizabeth Ballard, along with their two small children, William and Mary. Their home had been burned down in the fighting in Arkansas, so they were heading toward Springfield to stay with relatives. People in the town of Batesville still remembered the image of the four of them on an old wagon carrying a few bags of belongings, their faces tired but trying to hold onto hope.

They were last seen in Forsyth, then vanished. That year, anyone who went missing was easily written off as being swept away by the war. But when a little girl’s dress with distinctive embroidery and a small plaid shirt belonging to William were found at the Keller farm, no one could doubt it anymore. Most heartbreaking of all was the case of Emma Walker, a young 19-year-old teacher.

The school where she taught was forced to close due to the war. She wrote a letter to her family in Springfield, saying she would be home in July. In her last letter, Emma said she had asked for a ride on a merchant’s wagon and told her parents to wait. But they waited in vain, left only with sleepless nights. Her desperate father wrote a petition to the army, pleading for them to find his daughter’s whereabouts. The response was only silence.

Years later, among the scorched items at the Keller farm, there was a small locket; inside was a faded portrait of a young girl. Her father confirmed it was a family keepsake. There was no longer any doubt; that young girl had stopped at the house that should have offered safety.

You see, those names are not just faint lines of ink in a ledger. It is a father wanting to return to his family; it is a whole family seeking a new home; it is a young girl on her way back to her parents’ arms. All disappeared as if the road had swallowed them whole. But in reality, they all stopped at the same place, under the same roof, which perhaps at that moment opened its door with a social smile.

What is scary here is not just the number of missing people, but the manner of their disappearance. It happened quietly, in an orderly fashion. Person after person went missing, not scattered across the region, but all converging on a single stretch of road. But because of the war, no one had the energy to map those faint traces. The county had no police, the courthouse records burned, the army was busy fighting.

And so, each name vanished like a drop of water falling onto stone—evaporating without anyone bothering to count. But not everyone who passed by failed to return. A few escaped, and it was their trembling accounts later on that revealed part of the curtain. One of them was Jacob Cranston. He recounted that when he passed the Keller house late in the afternoon, Abraham called out: “The road isn’t safe tonight. Many deserters are prowling; it’s better to stay over.”

Jacob was invited for dinner, a hot stew, but he realized he was the only one eating. The people in the house watched silently. When he made an excuse to go to the stable, he heard the sons whispering, “Check the hooks in the smokehouse.” A chill ran down his spine; Jacob decided to flee into the night, leaving behind his saddle and his bag.

He ran for two days until he met a Union patrol unit. Another case was Mary Wham. She wrote a letter recounting that when their wagon broke a wheel near the river, the Keller family came out to help. The father and sons eagerly fixed it, while Edith and the two daughters brought out food. But Mary’s children were sharp enough to notice a dried bloodstain on the apron of one of the girls. Mary brushed it off at the time, thinking it was just a trace from killing a chicken.

But her husband noticed that there was no livestock around the house—no breeding bull, no flock of chickens. A wealthy farm that raised nothing. It was too strange. He whispered and then urged the whole family to move on immediately that night. Imagine, if Jacob hadn’t had enough intuition to run, if Mary hadn’t listened to her husband’s urging, perhaps they too would have remained on the missing persons list.

The terrifying thing here is that they didn’t escape because of clear evidence, but because of a gut feeling, a tiny observation, a sentence, a bloodstain, a moment of silence. Sometimes it is those small things that save a life. Meanwhile, in Forsyth, people still whispered about the strangeness of the Keller house, but then ignored it because every family had its own worries.

Some lost sons in the army, some lost crops, some worried their land would be stolen tomorrow. Everyone had enough pain, so they chose not to look at another pain. Only when the stories of disappearances grew long, when whispers became rumors, did fear begin to spread. Not fear of the enemy on the battlefield, but fear of the house right by the road where the kitchen smoke looked so peaceful.

Have you noticed? Evil rarely arrives with a roar; it comes with a social smile, with an invitation to come in and eat to warm your belly. The traveler is weary, their heart yearning for a place to rest. And when the door opens, few still suspect anything, and that very trust turns into a noose.

The disappearances from April to November 1862 were like nails being driven into the same coffin one by one, but at the time, no one saw it. Only looking back did people shudder, realizing every grain in the wood led back to the same hand. And that hand was not from the enemy army, not from forest bandits, but from a family with a polite and gentle appearance right within the community.

When thinking of those vanished faces—Jonathan with the silver watch, the Ballard family with the two chattering children, Emma with the old textbook in her bag—I don’t see them as names in a file. I see them as shadowy figures walking on a dusty road, glancing back one last time before stepping through the Keller gate. And that step had no return path.

There are things that, if you only hear about them, you still want to believe are fabrications. But when held in your hand, when the black ink has dried on yellowed paper, the feeling it leaves is more terrible than any rumor. With the Keller family, what remained at the end was a small notebook hidden behind a brick in the chimney, found nearly a hundred years later when the house had been destroyed.

People call it “The Devil’s Diary,” and perhaps no name is more fitting. The book isn’t thick, the paper is coarse, and each page is stained with smoke and mold. But what can still be read is enough to make anyone’s hands shake. There are no long stories, no emotional lines, just dry, brief notes like an accounting ledger.

Each entry begins with a few words: “Male, approx 30 years old, healthy, 67kg, usable.” Or “Female, old, poor quality but bones good for boiling stock.” Line by line, cold and neat. As if they were recording the butchering of a cow or a pig. The horror here is not just the content but the way it was recorded, showing a complete separation from humanity.

A normal person, if they accidentally did something wrong, would show at least some regret in a diary, or at least avoid the details. But not here. Here, there is clarity, standards, quality assessment, and productivity recording. Reading through a few pages, you realize they viewed humans as no different from livestock, and they—the whole family—were the herders, the butchers, the preservers. There is a passage written in September 1861:

“Subject young male, healthy, good muscle-to-fat ratio, needs processing within 4 hours of intake to maintain quality.” Another line, January 1862: “Preservation method using snow and salt more effective. November batch still good after 60 days.” Think about it—that is no longer an impulsive act born of hunger or fear. That is the result of a process of testing, comparing, and learning from experience.

It is progress, but progress in a direction that just hearing about makes one’s spine run cold. In some surviving pages, there are symbols resembling those in livestock breeding books: numbering, dating, listing processing methods. There is even a section mentioning using bones for tools and skin that could be utilized.

I read to that point, my heart heavy as a stone, asking myself how much those people must have had to break their own humanity to write those lines with such a calm tone. What is more telling is that later researchers discovered the handwriting in the notebook belonged to more than one person. The strokes changed—some slanted, some rigid, some small. This means not only Abraham, the father, but many other family members participated and wrote directly in it.

This shows that the complicity was not temporary coercion but a lifestyle maintained by the whole family. From parents to children, everyone had a role. The recorder, the processor, the cook, the lookout—like a closed circuit. Only the output product was different: people. Those diary lines were later described by Dr. Eleanor Mayhew, who spent her life studying the Keller case, as a separate moral system detached from general society.

In it, humanity was replaced by pragmatic calculation. It sounds dry, but its meaning is incredibly haunting. In that house, there was no longer a concept of what a human was, other than how much meat, how much bone, how much fat they could provide. I remember forever the assessment of Dr. Richard Caster, a bioarchaeology expert, upon reading the notebook:

“This is not impulsive crime; this is a profession.” After hearing that sentence, I had to sit silently for a minute. A profession. It is truly terrifying when there are people who have turned cruelty into daily work. There are records, books, and improved methods.

And when the whole family participates, it is no longer individual behavior but a miniature culture, a dark culture erected in the midst of an isolated mountain region. If you ask how it felt reading those diary lines, I would say it was like hearing metal scraping against cold ice—shrill and making one’s skin crawl. It doesn’t scream, it doesn’t wail, but it leaves an echo that lasts forever, making you still hear it somewhere in your mind at night.

The horror does not lie in gruesome words but in the coldness to the point of apathy. When humans can write about their own kind in the language of a slaughterhouse, the final line between man and beast has been wiped clean. I still remember a short, rigidly handwritten line: “June 12, reserves full, no need to replenish for two weeks.” That line sounds exactly like a note in a family expense book.

The only difference is that the “reserves” here are not potatoes or pork, but human beings. And what makes people shudder most is imagining them writing that sentence—perhaps sitting around the dinner table, pen in hand, next to the sound of spoons hitting bowls, noting down market chores like a normal family.

Those pages are now kept in an archive under special conditions; few are allowed to see them. People are afraid not only because of the gruesome nature but because of the way it lets us peer into the abyss of human nature. Because if a family could build a world together where humans are just a supply source, who can be sure that such horror cannot recur somewhere else in another form?

Closing the notebook, I suddenly realized there are crimes that don’t need weapons, don’t need screams, don’t need splattered blood to make people afraid. Just a few lines of text are enough for us to see clearly how people turned the unthinkable into the everyday. And from there, I understood that the deepest fear comes not from a scream, but from cold silence.

December 1862, the Ozark sky was submerged in bitter cold. Winter winds blew across the ice-covered mountain slopes. The sound of dry leaves rubbing against each other sounded like teeth grinding in the night. A Union cavalry troop led by Lieutenant Samuel Radford was pursuing a group of Southern guerrillas, but a blizzard suddenly struck, forcing them to seek shelter. And like a dark fate, they stopped at the exact Keller farm.

The house at that time looked abandoned. The main door was ajar, snow covering a thin layer on the threshold. But when the soldiers entered, they realized the ash in the fireplace was still hot, meaning the family had left not long ago. Radford ordered a search, hoping to find food or blankets for the night.

However, what they found turned that patrol into the most haunting memory of their lives. In a letter to his brother in Illinois, Corporal James Harper wrote: “We thought we would find potatoes, rice, or bacon, but in the stone smokehouse, we saw slabs of meat, and when looking closely, none of us dared to call it pork or beef anymore.

It was meat that, as soon as the torchlight hit it, we all simultaneously gagged.” The whole squad stood frozen. No one could speak. There were body parts neatly cut, hanging on iron hooks; there were barrels of brine containing things everyone knew but no one dared to name. In the basement, the scene was even more terrible. A deep cellar with damp stone walls, a black earthen floor, and in the middle, a pile of human bones stacked high like firewood. Many bones were split in half, revealing knife marks used to extract the marrow.

In the corner was a huge copper pot, the inside stained dark brown. No one needed to say it to understand what it had been used to cook. The walls were hung full of tools—knives, saws, axes—all sharpened and arranged in neat order. A soldier who used to be a butcher wept when he saw the scene. He said, “No one could arrange it like this if they didn’t do it every day. This is a slaughterhouse.”

But a slaughterhouse for people. The diary of Private Thomas Renner recorded a detail that made people’s hair stand on end. In a small room next to the cellar, there were iron rings attached to the wall, chains still stained with dried blood. In the middle of the floor was a drain leading outside, surely to drain blood. Everything was prepared as if this were a factory, not a home.

“I have been to the battlefield, seen comrades torn apart by artillery shells, but I have never seen a scene that made me despair of humanity like this.” In the main house, soldiers also found a wooden chest; when opened, everyone held their breath. Clothes of many people, from men’s coats to children’s dresses, all folded neatly with papers clipped to them recording dates, as if every victim was filed away.

There were also small boxes containing rings, watches, glasses, combs, all arranged neatly. It was that tidiness that was more disgusting than anything. A madman might kill people, but only a cold mind knows how to manage victims like inventory. I tried to put myself in the shoes of those soldiers. They were used to death, to bloody scenes on the battlefield.

But what they saw that night was not momentary brutality. It was an entire system, a routine maintained for years. And the normality in the arrangement made them no longer believe in the goodness of people. Some soldiers had to go outside and collapse in the snow, hands covering their faces, shaking violently—not from the cold, but from horror.

What made everyone shudder most was the absence of the Keller family. The house was warm. The stove ash was hot. Everything seemed to have just stopped. They had managed to escape just before the troops arrived. The feeling of knowing that the people who caused this scene were only a few steps away, hiding in the forest or watching from afar, made many soldiers draw their guns and stand guard all night; no one could sleep.

After gathering a few items as evidence—diaries, personal belongings, some tools—Lieutenant Radford ordered the farm burned down. In the report sent to his superiors, he wrote briefly: “What was found cannot be described in detail. All property has been destroyed to avoid the risk of spreading further evil. Request a thorough investigation after the war.”

That report was sent but then buried amidst thousands of other files of a country sinking in chaos. What remains for us today are private letters a soldier wrote home to his family. “If anyone asks what the most terrible thing I ever saw in my soldiering life was, I won’t mention the battles. I will mention the cellar of the Keller house.

I know demons exist, but those demons wore human shapes, lived together, ate together, and then united to do things I dare not name.” Reading those lines, I feel a lump in my throat. They say war calluses people to gore, but the truth is there are still scenes that make seasoned soldiers collapse.

Cruelty on the battlefield, though terrible, still falls within the framework of war. But here, it went beyond all frameworks. Here, a family turned evil into the everyday. And that is what made it more terrifying than the bloodiest battles. The Keller farm burned down that night, black smoke billowing against the winter sky.

The soldiers stood watching, feeling both relieved and tormented. They knew they had witnessed a terrible secret with their own eyes and also knew no one would believe them if they told it in enough detail. Perhaps that is why, years later, the story was shelved, existing only in letters sent to relatives.

But the fire that night could not erase the memory; it only turned the memory into a scar, so that every time it was touched, one felt a sting in the deepest part of their faith in humanity. The Keller farm burned down in the winter of 1862, but that fire could not burn away all the questions. The most tormenting thing was that the family vanished without a trace. Abraham, the children—all evaporated into the darkness.

Where did they go? How did they live? And most importantly, did they continue to do the same thing elsewhere? Who knows. And that very ambiguity makes the story even more haunting. After the war, Missouri and Arkansas were still in shambles, so few cared about investigations. The Keller case file was buried amidst mountains of other reports, from looting and fires to military massacres. But in scattered scraps of paper, we still encounter strange signs.

A report in 1865 from the Arkansas Gazette offered a reward for information about a strange family named Keller, suspected of involvement in disappearances, but there was no reply. Then, in the late 1860s, the Hardy region of Arkansas discovered a mass grave with twelve skeletons, all bearing cut marks similar to what Union soldiers saw at the Keller farm.

They excavated, made sketchy notes, and then ignored it because the case was too old, and the perpetrators were surely dead. But this coincidence makes anyone who reads the file shudder. Did that family leave Missouri, continue their human hunting game in Arkansas, and then vanish again before being caught?

Other puzzle pieces appeared in Texas in 1870. In the census records of Bee County, a family named Holland was recorded. The number of members, ages, and names were almost identical to the Kellers. Abraham became An Holland, then Elisa, Tobias, Gideon, Elias, Miriam, Abigail. With only slight changes. It was also noted that strange disappearances occurred continuously on the trails around that area.

Documents from the Texas Rangers in 1873 also described a suspicious house with an underground cellar and unusual tools. When the Rangers arrived, the house was abandoned, leaving only wooden barrels half-filled with a substance the accompanying doctor refused to identify. The case was closed with a few lines: insufficient evidence. Then there was a rare letter written by William Burnett, a Confederate veteran, to his friend in 1867.

In it, he recounted meeting a strange family that had just moved from Missouri. They invited him for dinner, but he refused when he noticed the eyes of the old, gaunt father. The grey beard and the scrutinizing gaze, as if appraising a horse. He caught a glimpse of a large smokehouse behind the barn and a son hurriedly blocking him when he showed interest in seeing it.

Burnett wrote: “I shuddered and hurriedly made an excuse to leave immediately. That night I couldn’t sleep.” Reading it again, one can’t help but shudder; perhaps Burnett was lucky to escape. Particularly, there is a medical document from the Texas State Asylum in 1878 recording a male patient, code CH, falling into a state of paranoia and depression.

This person claimed to have been a member of a human-hunting family, describing dark cellars, iron chains, and salted meat. It was noted he was in his 30s, matching Elias Keller, the youngest son. The patient died just a year after admission. Of course, we cannot be certain it was Elias, but that piece makes the picture even more haunting. The story didn’t stop there.

In 1968, an old woman in a nursing home in Texarkana suddenly claimed to be Abigail, Abraham’s youngest daughter. In her moments of confusion, she spoke about helping her father in the stone smokehouse, about preparing dinner from strangers. When lucid, she denied everything, insisting it was just a dream. The staff recorded it, but no one could be sure if she was really Abigail or just delusional and infected by rumors.

She passed away early the following year, taking the secret to her grave. You might ask, why with so many sources, did people not pursue it? In truth, in that context, the whole society was struggling to rebuild after the war, worrying about food and clothing, worrying about unstable laws. Who had time to hunt down a family that had disappeared for decades? And as time went on, those patchy pieces of evidence gradually turned into legends, then into ghost stories in folklore.

I think what scares people is not just what the Keller family did, but the feeling that they might still be out there somewhere. Continuing in the darkness, changing names and appearances, living among the normal community. Evil, when clearly visible, we can fight. But when it blends into life, wearing ordinary clothes, it becomes an endless obsession.

When reading the scattered notes, I always feel like there is a fog hanging across them; nothing is clear, just a few faint footprints, a few small bloodstains, and then everything dissolves into darkness. But that very obscurity is what is terrifying. Because we don’t know where it ends, or even if it has truly ended. There are stories so terrible that even if the perpetrators have disappeared, the darkness they left behind still clings like smoke that won’t dissipate.

The Keller case is such an example. After the farm was burned and scattered traces appeared across Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas, people were no longer sure what was truth and what was just rumor. But there is one thing everyone sees clearly. That evil did not disappear in a night.

It left a scar in the community’s memory, deeply ingrained in the way the Ozark people view the world. Dr. Jonathan Wells, a criminal psychologist, once said Abraham Keller had all the signs of antisocial personality disorder. He was not only emotionless but also dragged his whole family into an inverted moral system where humans were merely a reserve resource. Even more horrifying is that the children growing up in that environment viewed chopping bones, salting meat, or classifying victims as no different from plowing fields or feeding livestock.

A family, instead of being a place to teach humanity, became a machine that swallowed humanity whole. Looking back, researchers believe the horror lies in the fact that this family did not act simply out of hunger or despair. They calculated, they recorded, they perfected their methods.

From Abraham to Edith, from Tobias, Gideon, Elias to Miriam, Abigail—no one stood outside of it. This turns the story into a rare proof that an entire small social unit, a family, can walk together into the deepest darkness. And that is what makes people shudder more than ghosts. I remember a sentence in Wells’ report:

“When a person kills, we call them a murderer. When a whole family turns killing into a lifestyle, it is a culture.” Reading that, my back felt ice cold. Culture is supposed to be what helps humans progress and bond, but in this case, it was twisted into a tool to rationalize crime. The impact the Keller case left on the Ozarks was significant.

The people here traditionally had a culture of hospitality; amidst the treacherous mountains and forests, passersby were often invited to stay and share a meal. But after the story broke, many families began to suspect strangers. There is a letter from 1863, a resident in Forsyth wrote to relatives in St. Louis: “Since the Keller affair was discovered, no one dares to let strangers stay overnight anymore.

Doors are locked tight, eyes are wary. We fear kindness will betray us.” Just one family was enough to destroy the thread of trust that had helped the whole region survive for generations. Today, the place where the farm once stood is submerged under Bull Shoals Lake after the dam was built in the 1950s.

People might say the calm water has covered the past, but those who know the story understand that the lake is like a blanket spread over a giant grave. Beneath are fragments of memories, secrets, and echoes that never dissolve. Some people fishing on the lake swear that at night they hear the sound of chains dragging clankingly at the bottom. Others claim to see flickering firelight right at the deep water.

But I think no ghost needs to appear; the truth about that family alone is enough to make this place forever terrifying. I have often thought about what made a family choose that path. Was it the war, the isolation, the hunger that pushed them to slide, or did they already carry the seed of evil within them, just waiting for this opportunity to bloom? Perhaps we will never know.

But what is certain is that once humans accept viewing their own kind as assets, as items to be used, the final boundary of humanity has been erased. And when that boundary is erased, evil has no limits. There is a detail I remember forever. In 1968, when the old woman in Texarkana, who claimed to be Abigail, in her confusion mentioned helping her father in the stone smokehouse, the nurses recounted that her voice did not tremble at all.

It was as light as if recounting a daily household chore. That makes me feel colder than when she was delirious because it suggests a terrible possibility. Perhaps to that family, it was all just living—not torment, not a secret, but a way of life passed from parents to children.

Some say the Keller case was just an exception, a tragedy that will never be repeated. But I think the very fact that it happened once is enough to warn that in the right circumstances—isolation, chaos, lawlessness—anyone can slide into the abyss. Evil does not always erupt with knives slashing and guns firing.

It can begin with a small thought: “Others are just a means for my survival,” and from there it grows until it turns the whole family into a machine. Finally, what haunts me most is not the bones, not the diary, but the words of an old man in Taney County recorded by Dr. Eleanor Mayhew: “There are things that should not be forgotten. Even if remembering them is just clotted blood in the heart.”

The Kellers are gone, but remembering them might help people be more cautious. “Don’t easily trust a dinner invitation.” It sounds simple, but it contains an entire philosophy of survival. Because ultimately, the most terrible evil often does not knock on the door with a scream, but softly, like an intimate invitation.

Perhaps what remains most deeply after hearing the full story of the Keller family is not just the shudder at the crime, but a reminder of the fragile nature of humanity when law and social order collapse. When humans fall into isolation, hunger, or fear, the line between good and evil can be blurred faster than we think.

The Keller family created their own laws. A place where humans remained only as a source of benefit, a means to exist. And that very thing makes us realize that evil is not always noisy or impulsive. It can be nurtured silently, becoming a habit, then a lifestyle if we are not vigilant.

In life today, we do not face such harsh conditions as in the Ozarks back then. But the lesson remains valid. Cherish humanity. Place compassion and trust above personal gain. Kindness can be the thing that keeps us back from the brink, keeping us from sliding into darkness. Every small action—a handshake, a thank you, an act of sharing—contributes to affirming that we choose to stand on the side of light.

If you feel this story brought you something to think about, please leave a comment on what content you would like me to share in future videos. Don’t forget to like and subscribe to the channel so you don’t miss the next journey. Wishing you a peaceful, warm day full of hope.

News

German Pilots Laughed at This “Useless” P-47 — Until It Destroyed 39 Fighters in One Month

German Pilots Laughed at This “Useless” P-47 — Until It Destroyed 39 Fighters in One Month At 0700 on October…

The Hazelridge Sisters Were Found in 1981 — What They Said Was Too Disturbing to Release

The Hazelridge Sisters Were Found in 1981 — What They Said Was Too Disturbing to Release In the winter of…

Why Would a Rich Young Man Be Accused of Doing This to His Mother?! The Bizarre Case Nathan Carman

Why Would a Rich Young Man Be Accused of Doing This to His Mother?! The Bizarre Case Nathan Carman There’s…

When Excavators Dug Beneath the Old Church, They Found the Devlin Family’s “Final Meal”

When Excavators Dug Beneath the Old Church, They Found the Devlin Family’s “Final Meal” There are places where the earth…

16-Year-Old Girl Becomes Richest Widow: The Mysterious Deaths of 8 Husbands

16-Year-Old Girl Becomes Richest Widow: The Mysterious Deaths of 8 Husbands Do you believe in bad luck? Or do you…

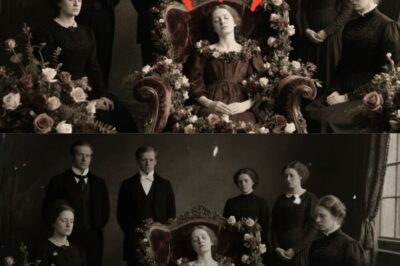

The Perfect Crime Hidden, Until This Funeral Photo “Speaks”

The Perfect Crime Hidden, Until This Funeral Photo “Speaks” Take a close look at this photo. It looks just like…

End of content

No more pages to load