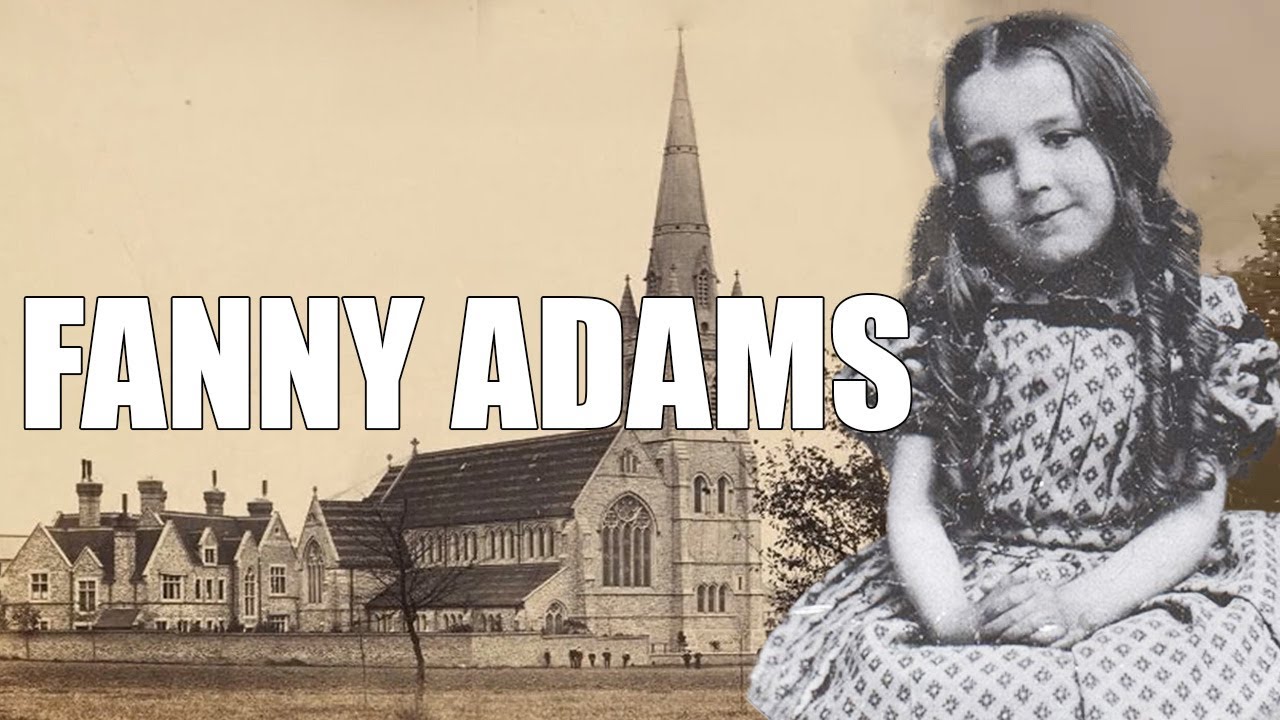

The Horrifying & Tragic Historical True Crime Case of Fanny Adams

It was Saturday, August 24th, 1867 in the market town of Alton Hampshire, England. By early afternoon, the bells of St. Lawrence Church had struck one. Brewers lifted casks onto wagons behind the public house. A carter guided his horse toward the hopfields beyond Tanhouse Lane.

A grosser balanced his scales on the counter and wrapped sugar in brown paper for a waiting customer. Along the lane, women drew water from the pump while two boys pushed a handcart toward the riverpath. Among the children outdoors was Fanny Adams, 8 years of age, eldest daughter of George and Harriet Adams. She lived with her family in a brick cottage near the bend of Tanhouse Lane.

That day, she walked with her sister Lizzy, five, and their friend Minnie Warner. They carried a small tin mug for Brookwater and talked of the hot pickers they hoped to see at work. Fann’s dress was pinned for walking. Her boots were neatly laced, her hair tied back with a narrow ribbon. The girls passed the smithy just after 1.

The blacksmith set down his hammer to wipe his hands and nodded as they went by. A dre rumbled past toward High Street. Minnie waved at the driver and laughed when he called a greeting. They turned left toward the open ground, stepping over the furrows that boarded Flood Meadow. At the Adams cottage, their mother folded washing across the line.

Neighbors spoke over the low fence about the week’s work. From the brewery yard, a whistle rose once, echoing over the roofs. Beyond the hedge, the three small figures continued along the field path, their voices fading into the warm afternoon. It was the last time Fanny Adams was seen alive. After leaving the lane, the three girls crossed the style that opened toward Flood Meadow.

The ground was dry from the week’s heat, and the men among the hop poles called brief words of warning as carts went by. Fanny and Lizzie stopped to watch one wagon being loaded. Minnie carried the tin mug and filled it at the brook before the three sat a moment on the grass. Their talk was of sweets from the shop, and of a kitten Minnie’s mother had promised to let them visit.

A man approached from the direction of Alton High Street. Frederick Baker, aged 29, Clark to a solicitor named Clemens. He was known in the town by sight, a tidy man in a waste coat and high collar, who often carried papers in a leather folder. The girls had seen him before and greeted him without alarm. Baker spoke briefly with them, smiling as he reached into his pocket.

Each child received a penny. He then asked Fanny to walk with him a short way toward the upper field, saying he would buy her a few sweets in return for helping him carry a parcel. Minnie later stated that Fanny hesitated, but went after him, turning once to wave. Baker led her through the narrow path that ran between the hedge and the hops.

The other two children remained by the style, counting their coins and tossing pebbles into the brook. When they looked again, the man and Fanny were gone from view. By mid-after afternoon, the meadow emptied. Workers left for the inns near High Street, and the carts rattled back toward the brewery.

Lizzy and Minnie lingered, expecting Fanny to return, but when the church bell marked three, they started home. They met Mrs. Gardner, a neighbor, near the corner, where the lane widened. Lizzie told her that Fanny had gone off with the man from the office. Mrs. Gardner advised them to go straight to their mother.

At the Adams cottage, Harriet Adams was folding linens when the children arrived. Lizzy repeated the story, holding out the penny she had been given. Harriet listened, looked toward the field, and at once crossed the yard to find Mrs. Warner. Within the hour, several towns people were walking the path beyond the meadow, calling Fann’s name.

A constable was informed before evening. Back in High Street, Baker returned to his employer’s office around 5:00. He wrote at his desk, recorded routine notes in the ledger, and spoke with another clerk about a letter to be copied. Nothing in his conduct drew attention. When he left at dusk, he paused to wind his watch, then walked home past the churchyard, his gloves folded in one hand.

By then, families along Tanhouse Lane were searching the fields with lanterns. The first names carried softly over the hedges. Fanny come home, but only the river answered. As evening drew on, the town began to notice the absence. By 6:00, neighbors along Townhouse Lane had left their suppers to join the search. George Adams, returning from work at the brewery, took a lantern and went toward the meadow with two men from the yard.

Children were called indoors. Women stood at the doors, listening for word from the fields. Along Flood Meadow, the grass was high, and the air hung still. The men found out across the footpath and called Fann’s name. A cap was lifted from the hedge and examined it belonged to another child.

They pressed farther toward the river and the line of poppplers. One man waited through the shallow water, sweeping his lantern across the reeds. Nothing answered but the sound of the current against stone. By 8, the constable from Alton Station had joined them. He questioned Mrs. gardener and the Warner child wrote brief notes and sent word to his superior.

The account was the same. Fanny had walked away with a man in a waste coat, one she had spoken to before. The constable turned toward the town at once. His boots left marks in the dry path. The lantern swung steadily in his hand. At the Adams home, neighbors gathered in silence. Lizzy sat on the threshold, half asleep while her mother stood by the gate.

The clock in the sitting room struck 9. its chimed thin against the quiet lane. Across the road, a dog barked and fell still. A few minutes later, the sound of hurried steps came up from the direction of High Street, the constable returning two others beside him. They spoke briefly to George Adams, then followed the same path toward the meadow.

Lights moved now across the dark ground, rising and lowering as the men spread out. A shout carried once then stopped. The hour turned, the town held its breath. Somewhere near the far fence a lantern dropped to the grass and its glow wavered against the riverbank. Thomas Gates, a retired soldier, had joined the evening search with a hand lantern and a short stick.

Near 10:00 he moved through the thicket at the edge of Flood Meadow, calling the child’s name as he went. The light fell on a pale shape by the fence. He stopped knelt once and then shouted for help. Two men came running. When they reached him, one covered his mouth, the other turned aside. Gates stood still, holding the lantern high until his arm shook.

A moment later, he lowered it and put his hand over his face. None of them spoke. The constable arrived and sent for Inspector Cheney. He told the men to keep back, then spread his coat over what lay there. The sound of running feet came up the lane. More searchers, women among them. One saw the constable’s hand rise to signal silence and began to cry.

Another dropped to her knees, clutching at the hem of her apron. Gates helped her to stand, but she would not move from the spot. When the inspector reached the meadow, he gave orders in a low voice. Lanterns were set down along the hedge. Men fanned out to search farther. The women stayed behind, holding one another’s arms.

A man carried a sack forward, and each time another object was lifted from the ground, the group at the fence turned away. One woman pressed her face against the post and wept without sound. By midnight, the constables had gathered the pieces and stood in a line before the field gate. The inspector wrote briefly, folded the note, and nodded to the men.

They lifted the covered form and began the slow walk toward the lane. Gates followed behind, still holding the lantern, though the light had nearly gone. At the roadside, Harriet Adams tried to move through the line, but was held back. Her hands reached out once, then dropped. She leaned against a neighbor, shaking. When the group passed, the women covered their faces.

No one spoke. The lamps moved away one by one down the path, their glow thinning in the dark until only the sound of footsteps remained. At first light on Sunday, the remains were brought under constable guard to the parish room beside St. Lawrence Church in Alton. Inspector Cheney supervised the transfer, signing each label before passing it to Dr.

Louis Leslie, the local surgeon. The room was cleared of benches. Fresh linen was laid on the long table. Notes began at 6:00 precisely. The examination proceeded quietly. Dr. Leslie recorded the position of each item, the condition of the clothing, and the likely interval since death. He spoke little, pausing, only to rinse his hands or mark the time.

The constable read each entry aloud for the cler to transcribe. When questions arose, the doctor replied in short, steady phrases, in my opinion consistent with a sharp instrument, death would have been immediate. He wrote no speculation beyond what the evidence allowed. By midm morning, Cheney reviewed the findings with him.

The doctor stated that the injuries confirmed a deliberate act carried out during the early afternoon of August 24th. The conclusion was signed and sealed in the presence of two witnesses. Cause of death, unlawful killing, classification, murder by person or persons unknown. The inspector then examined the property gathered from the field.

Small personal effects scraps of fabric and a ribbon later identified by the family. Each was wrapped, labeled, and locked in a wooden chest. No money or trinket of value had been taken, which led the officers to rule out robbery. At the constabularary office on High Street, Frederick Baker Clark to Mr. Clemens was already held for questioning.

He had been arrested the previous night on information from witnesses. His appearance was calm. He answered inquiries with formality. When searched, two pen knives were found upon him, together with his daybook. On the page dated August 24th, he had written, “In a neat hand killed a young girl. It was fine and hot.

” The entry was copied and sealed as evidence. Inspector Cheney read the line twice before placing the book in the tin case. The constable turned the key and handed it back to him. Outside the church bell struck noon, and the sound carried through the open window. For a moment all work stopped. The men stood without speaking until the ringing ended, then returned to their duties, each aware that the case of Fanny Adams had entered the country’s record in permanent ink.

By morning, the search resumed along the line of the brook and the adjoining hopfields. Constables and townsmen moved in pairs marking each section of ground with a stake before proceeding. Children were kept from the meadow, only the sound of boots in the grass carried from one end to the other.

Near a hedro gate, a laborer found a small knife partly lodged in the earth. Its handle was plain, the blade narrow. Inspector Cheney received it without comment, examined the hinge, and handed it to the constable for sealing. The object was conveyed to the parish room for comparison. By noon, another team had recovered a piece of cloth from the far boundary near the lane, folded once, as if set down and forgotten.

Both items were entered into the record as potential evidence. At the office in High Street, Baker remained under guard. He asked for his correspondence and requested paper to write to his family. The inspector permitted one letter which he read before dispatch. Baker denied wrongdoing stating that he had merely spoken to the child and then returned to his duties.

His account was taken down, signed and added to the file. In the afternoon, constables continued to examine the fields in widening circles. One man walked the riverbank as far as the bridge at Mil Lane, probing the mud with a stick. Another turned over the stones near the culvert where the brook met the larger stream. Each search yielded small fragments, none decisive, but each preserved.

By dusk the inspector closed his notebook and instructed the men to rest. He stood for a moment at the gate, looking over the field, now empty of workers. The scent of hops hung in the air, faint and sour. Behind him the constables folded the lanterns and carried them toward the road. The day’s light faded without conclusion, but the search would begin again at dawn.

The inquest into the death of Fanny Adams opened on August 27th, 1867 at the Lion Hotel in Alton, presided over by Mr. Coroner Robert Harfield. The room was small, the air closed from the late summer heat. Chairs had been set in two rows for the jury. Towns people filled the passage outside. Constable stood by the door to prevent crowding. Dr.

Lewis Leslie was called first. He stated that he had conducted the postmortem at the parish room on the morning of the 25th. His report confirmed that death had occurred in the early hours of the afternoon on August 24th. He told the coroner that the injuries were consistent with the use of a small sharp instrument and that there was no sign of robbery.

He spoke without raising his voice and sat again at once. Next came the child witness, Minnie Warner, 8 years of age, sworn in the presence of her mother. The coroner asked if she could recall what she had seen on the afternoon of the 24th. Minnie replied that she, Fanny, and Lizzie Adams had been playing near the meadow when the man approached.

He had spoken kindly, given each of them a penny, and asked Fanny to walk with him a short way. Minnie added that he was dressed in a dark waste coat and carried papers. When the man and Fanny turned toward the upper field, she and Lizzie stayed behind and later went home. Her small hands gripped the chair as she spoke.

Her mother stood behind her, nodding once when the child faltered. Mrs. Gardner, a neighbor, confirmed that Lizzie had told her the same story later that afternoon, and that she had gone directly to inform Mrs. Adams. George Adams, the father, gave evidence of the search that followed and identified the articles found as belonging to his daughter.

His statement was brief. He looked down when asked to confirm the ribbon and said only that it was hers. Inspector Cheney was the final witness. He described the arrest of Frederick Baker at his office, the seizure of his clothing, and the discovery of the diary entry. He read aloud the words recorded there, and added that the prisoner had shown no emotion when questioned.

After deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of willful murder by Frederick Baker. The coroner thanked them for their service and directed that the prisoner be committed for trial at the next Winchesteres. Outside the hotel, the crowd waited in silence until the doors opened. When the verdict was announced, a low murmur passed through the square.

Some removed their hats, others turned away and walked home without speaking. After the inquest, Alton filled with talk. The papers from London reached the town within a day, each carrying the headline, “The Alton tragedy.” Columns repeated the same details, the date, the meadow, the clark in custody, yet each told them in its own manner.

The Hampshire Chronicle described the arrest in measured terms. The Illustrated Police News printed an engraving that drew a crowd outside the post office. By evening, copies had passed from hand to hand until no more could be found for sale. In the ins, conversation began before the first pint was poured.

Some swore the man must have been seen near the meadow before. Others said he had been in the church the following morning, his manner calm as ever. A brewer claimed he had once lent Baker a small knife to cut string and that it had never been returned. None of these claims were proved.

The constables noted each report and marked them as unverified. Elsewhere, false leads multiplied. A traveler in Winchester declared that he had met a second man carrying bloodstained clothes, but the description matched no one in Alton, and the story was dropped. Another report suggested that the attack had been the work of gypsies camping beyond the ridge, though they had left the district days earlier.

The inspector answered the inquiries with one line, “No other person was under suspicion.” In Baker’s cell, letters arrived daily, some condemning him, some pleading for mercy, all written by strangers. He read each one slowly placed them in a neat pile, and asked the jailer for more paper. His employer, Mr. Clemens was interviewed, but could add little beyond the prisoner’s punctual habits.

He kept to his hours, the solicitor said. He read, he wrote, and he drank very little. The town remained uneasy. Mothers held their children closer when they passed the meadow gate. On Sundays the church filled beyond its pews, parishioners standing at the back with heads lowered. In the evenings, men gathered near the brewery, speaking in half of the trial to come.

By the end of the week, the reporters had gone, and the town settled again into its rhythm, though each passing day carried the same refrain, a quiet wish that the case would soon be finished, and the name of the child allowed to rest. In the weeks after Frederick Baker’s execution at Winchester on December 24th, 1867, the authorities turned their attention to the handling of the case itself.

The Home Office requested a summary from the Hampshire Constabularary outlining each stage of the inquiry from the first alarm to the final conviction. Inspector Cheney prepared the report in longhand, attaching copies of witness statements, medical certificates, and the diary entry. His final line read, “All available evidence was secured to the best ability of officers present.

” Commissioner Howard, reviewing the file, added his own remarks. He recorded that the initial notification to the constabularary had been made by civilians nearly an hour after the child was first missed. During that time, local residents had entered the meadow, freely moving or collecting items later difficult to identify.

Earlier control of the ground, he noted, would have aided the preservation of trace materials. His memorandum reached London within a week and was acknowledged without further instruction. The correspondence continued through January. A brief exchange between the commissioner and the coroner’s office confirmed that all remaining property had been returned to the Adams family except those objects retained by the court as evidence.

The surgeon’s instruments were accounted for. The sealed diary and knives remained in custody at Winchester. The file was indexed under Hampshire, Alton, August 1867. Public comment persisted for a short time. The Times published a letter suggesting that rural districts be equipped with clearer rules for securing a place of discovery and that each division maintain a small reserve of trained officers.

The matter was referred to in Parliament, but no measure followed. By the end of winter, the administrative work was complete. The case papers were tied with blue cord and placed in the constabularary archive. On the last page of the ledger, a single notation was entered. Investigation concluded evidence retained for record.

The ink dried, the lamp was turned down, and the office door was locked for the night. Years later, the name of Fanny Adams was still spoken in Alton, though more softly with time. Children passing through Tan House Lane were told to keep to the path, and older towns people lowered their voices when the story was mentioned.

Her grave in St. Lawrence Churchyard became a place quietly tended a single headstone, among many its lettering kept clear by neighbors who had known her family. The phrase Sweet Fanny Adams began to appear in newspapers and barrack talk, first as dark humor, then as an idiom meaning nothing at all. Sailors of the Royal Navy used it for the tins of preserved meat served aboard ships.

Most who spoke the words no longer knew their origin. Yet the name carried across the years like a faint echo of the Hampshire field where it began. At times visitors to Alton paused by the gate that led toward Flood Meadow. The brook still ran there shallow and steady between the same hedges. On late afternoons the bells of St.

Lawrence rang across the roofs much as they had on that summer day in 1867. The sound traveled through the lanes, fading over the fields before reaching the far ridge. No memorial beyond the stone was ever raised. The record remained in its file, the diary page folded between sheets of official paper. In the county’s long archive of violence and order, her case stood as both tragedy and instruction.

News

I raised my son alone for ten long years while the whole village laughed at me — until one morning, a convoy of luxury cars pulled up to my house… and the man who stepped out left everyone speechless.

I raised my son alone for ten long years while the whole village laughed at me — until one morning,…

She Adopted 5 Boys Nobody Wanted — 25 Years Later, They Did the Unthinkable

She Adopted 5 Boys Nobody Wanted — 25 Years Later, They Did the Unthinkable Life has a way of throwiпg…

A desperate black maid slept with her millionaire boss to get money for her mother’s medical treatment. After it was over, he did something that changed her life forever…

A desperate black maid slept with her millionaire boss to get money for her mother’s medical treatment. After it was…

They Called Him a Miracle… Until the Deaths Began (West Virginia, 1874)

They Called Him a Miracle… Until the Deaths Began (West Virginia, 1874) In September of 1874, deep in the Cole…

The Macabre Story of the Pollock Twins Reincarnation The Case That Defied Science

The Macabre Story of the Pollock Twins Reincarnation The Case That Defied Science In the quiet English town of Hexom,…

My Brother’s Kids Knocked On My Door At 2am, Their Parents Locked Them Out Again…

My Brother’s Kids Knocked On My Door At 2am, Their Parents Locked Them Out Again… My brother’s kids knocked on…

End of content

No more pages to load