The Good Son of Palmetto Hill Plantation — The Child Who Learned Mercy from His Father’s Cruelty

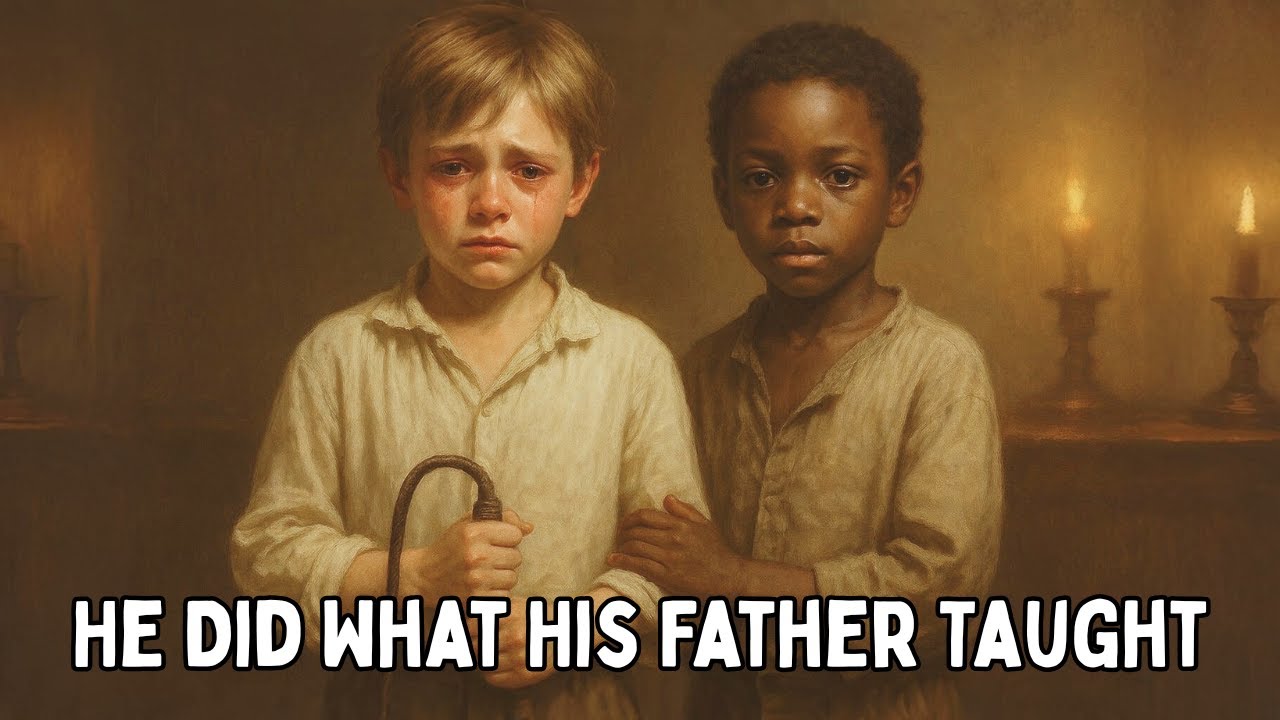

The summer air over Palmetto Hills smelled of rain and sugar and rot. They said every boy learns what kind of man he’ll become by 8. Henry Caldwell learned his lesson on the day his father smiled while a man begged for mercy. From that moment on, Henry thought kindness was power, and love was something you earned by obedience.

When his father told him to treat the slaves as animals that speak, Henry didn’t question it. He was told it was mercy to feed them, grace to forgive them, and strength to make them kneel. But when he met Isaac, a boy his own age, he learned that love could hurt worse than cruelty. Because Henry didn’t want to be his friend. He wanted to own him.

Before we begin, make sure you subscribe to the Macab Record and tell me in the comments where are you listening from tonight. Now, let’s go back to South Carolina, 1855, to the house on Palmetto Hill, and the boy who learned to smile like his father. The Caldwell plantation rose above the lands like a monument to something long dead.

Its white columns were streaked gray with mildew, the shutters hanging crooked, the magnolia too thick to let in light. From the road below, the house looked proud. Up close, it looked tired. 8-year-old Henry Caldwell sat at the long breakfast table, legs swinging above the floor, silverware gleaming before him. His father sat at the head, posture straight, eyes unreadable.

Across from him, his mother stirred tea she never drank. The morning silence was broken only by the sound of a servant’s footsteps as he poured water into Henry’s glass. “Not like that,” Henry’s father said quietly. The servant froze. You spill when you rush,” the man murmured an apology, but the water still trembled in his hand. Henry saw a vain twitch in his father’s jaw, a sign he’d learned to fear.

“Stop shaking,” the man said. “You make the boy nervous.” Henry’s mother whispered, “Robert.” But her husband’s glance silenced her. The servant steadied himself, finished the task, and stepped back. Henry wanted to thank him, but didn’t. His father’s rule was clear. Kindness had a place, and it wasn’t at the table. “Henry,” his father said, dabbing his mouth with a napkin.

“A gentleman doesn’t need to raise his voice to command respect. Do you understand?” “Yes, sir,” Henry said. “Good. You’ll start lessons with Mr. Payne next week, reading, figures, and scripture. A man should learn three things early. How to count, how to listen, and how to keep others in their place.” Henry nodded. His mother’s spoon clinkedked softly against her cup. She kept her eyes on the tea as if afraid to meet anyone’s gaze.

After breakfast, Henry walked to the back porch. The sun was already cruel, spreading light across the fields like judgment. He watched the workers move in slow rhythm, stooping, straightening, bending again. He’d been told they were family, but not the same kind. He wasn’t sure what that meant. A boy about his own age was carrying a bucket toward the stables, his shirt damp with sweat.

Henry had seen him before, but never spoken to him. Something about the way he moved, calm, quiet, steady, made Henry stare longer than he meant to. The boy noticed and gave a small nod. Not a bow, not fear, just acknowledgement. It startled Henry. He wanted to say hello, but his father’s voice still echoed in his head.

keep them grateful. He turned away. From the open parlor window, his father’s laughter drifted out, low, confident, the sound of someone who’d never once been unsure. Henry wanted to sound like that someday. He didn’t yet understand that he already did.

The lessons began in the study, where dust hung thick enough to glow in the light that slipped through the blinds. Henry sat upright in a wooden chair too tall for him, his legs swinging above the floor. His father stood by the window, polishing his pocket watch with a cloth so white it hurt the eyes. Do you know what time means, Henry? His father asked.

Henry thought for a moment. It’s when things happen. Robert Caldwell smiled faintly. It’s what separates men from children. A man commands time. A child waits for it. He snapped the watch closed and placed it on the desk beside a Bible and a riding crop. two symbols of order side by side. Henry knew that both could teach and both could hurt.

His father continued, “The world runs on three kinds of people. Those who command, those who obey, and those who pretend not to care who does either. The last kind are the ones who end up trampled.” Henry listened carefully. Every word from his father sounded like a law. “And what kind should I be?” he asked.

Robert knelt so that their eyes met. you, my son, will learn to command. But to do that, you must first learn to appear merciful. Mercy is a leash. It keeps the obedient near without letting them forget who holds it. Henry didn’t fully understand, but he nodded, repeating the sentence in his head so he could remember it later.

When his lessons ended, Mr. Payne arrived, a thin man with gray hair and a voice like dry wood. He taught Henry to write his name neatly, to measure columns of numbers, to read aloud from the Psalms. Obedience, the tutor said, is the root of order. By afternoon, Henry’s mind was buzzing with words he didn’t quite grasp. Discipline, grace, ownership. They all sounded heavy and important.

When he went to the porch for air, he found his mother sitting in her chair by the magnolia tree, staring toward the horizon. The light caught the edge of her pale hair, making her seem almost transparent. “Did you learn something today?” she asked. “Yes, Mom,” Henry said proudly. “Father says mercy is a leash.

” Her face twitched, a small crack of pain passing through her calm. She set down her sewing. “And do you think that’s true?” Henry hesitated. “He says it is,” she sighed softly. “Then be careful what you tie it around, Henry. Sometimes mercy is all that keeps a person human. He didn’t know what to say.

Her words sounded kind, but they felt like disobedience, and he’d been taught that disobedience was dangerous. That night, as he lay in bed, the phrase repeated in his head, “Mercy is a leash.” He wondered who held it, and whether one day he would. Outside, cicadas sang in the dark, and the magnolia petals fell silently onto the porch below, like tiny surrender flags.

It was a morning wrapped in heat, the kind that made the air feel alive, like it was breathing against the skin. Henry had escaped his lessons early, claiming a headache. His father believed him because Henry never lied. Not yet. He wandered down the path behind the stables, where the scent of hay mixed with the faint sweetness of molasses.

The cicadas were screaming, a sound that seemed to come from the ground itself. That’s when he saw him again. The boy from the other day, the one who’d carried the bucket without fear. He was sitting by the fence, tying thin twine around a broken toy horse, its leg splintered clean through. His hands moved with the careful patience of someone used to fixing what others broke. Henry stopped a few feet away.

You’re Isaac, aren’t you? The boy looked up. His eyes were dark and calm, not startled. Yes, sir. Yes, you don’t have to call me that, Henry said quickly, though part of him liked it. Isaac shrugged lightly. That’s what I’m told. Henry sat on the ground beside him, ignoring the dirt that clung to his trousers.

What happened to it? Stepped on, Isaac said, nodding toward the stables. Belonged to the master’s boy, I think. Henry felt a flicker of embarrassment. That’s mine, he admitted. I didn’t know it broke. Isaac nodded again, not apologetic, just matter of fact. It can be fixed. Henry watched as Isaac wound the string tighter, holding the pieces together until they formed a shape again.

It wasn’t perfect, the leg still bent a little, but it stood. Henry smiled, surprised by the small joy of it. “Thank you,” he said quietly. Isaac handed it to him, but didn’t smile back. “You’re welcome.” They sat in silence for a while, listening to the steady thud of hooves from the stables, and the hum of flies.

Henry wanted to ask him questions about his chores, his family, his life, but he remembered his father’s voice. There’s a line you don’t cross. Once you make them comfortable, you lose their respect. Still, curiosity pressed at him. Do you ever play? Isaac’s hands froze on the twine. Sometimes, he said cautiously. With who? Whoever ain’t looking, Henry frowned. You can play with me, he said. Isaac’s gaze met his.

You sure? Henry nodded. Father doesn’t have to know. Isaac’s mouth twitched. Not quite a smile, not quite disbelief. Then you best come where he can’t see. They crawled beneath the porch into a dim space that smelled of wood and dust and summer heat. The light filtering through the boards painted stripes across their faces.

For the first time, Henry felt something new. Not command, not power, but connection. It felt dangerous and good. When the dinner bell rang, he nearly forgot to answer. The space beneath the porch became their hiding place. Dust floated in the strips of light that broke through the floorboards above, and the smell of soil and wood mixed with the sound of faint laughter.

It was the one place where rules didn’t seem to reach. Henry brought a marble one day, smooth and blue like riverglass. Isaac brought a slingshot carved from a bent branch and a strip of old leather. They traded them for the afternoon, then traded them back before the sun sank. It became their game.

Exchange, return, pretend nothing changed. They talked about small things. Isaac told stories he’d heard from the older men. tales of rivers that could swallow sound, of stars that guided people when roads disappeared. Henry listened, spellbound. He’d never heard stories that belong to anyone but his father. “Do you ever leave?” Henry asked. Isaac shook his head.

“Ain’t nowhere to go that I’m wanted.” Henry frowned, rolling the marble between his fingers. “I’d want you.” Isaac’s eyes softened. “That’s kind, but kindness don’t open gates. Henry didn’t know what to say to that, so he changed the subject, asking about the songs Isaac hummed when he worked.

Isaac said they were old, older than the Caldwells, older than the hill itself. Henry wanted to learn them, but Isaac shook his head. Not yours to sing, Master Henry. The title stung this time. I told you not to call me that. And I told you I got to, Isaac replied with a half smile that wasn’t quite teasing.

The sound of approaching footsteps cut through the quiet. The boys froze. A shadow crossed the slats above them. Tall, deliberate, heavy. Henry recognized his father’s gate instantly. He pressed a finger to his lips. Through the cracks they saw the man pause at the railing, surveying the fields below. Then his voice smooth as oil. Henry.

Henry scrambled out from beneath the porch, dust clinging to his shirt. Yes, sir. What are you doing down there? Just playing. Robert Caldwell’s gaze flicked toward the shadow, still crouched under the porch. With who? Henry’s pulse thudded in his ears. No one, sir. Just myself. His father’s mouth curved into a faint smile. Good. A boy who can play alone learns not to depend on others. You’ll need that. He turned and walked away.

Henry stayed frozen until the sound of boots faded. When he ducked back down, Isaac was sitting with his knees pulled to his chest, quiet as stone. “You shouldn’t lie for me,” Isaac said. Henry’s throat felt tight. “If he knew, he’d stop me from seeing you.” Isaac studied him for a long moment, then nodded. “Then I guess we both lying now.

” They sat together until the sun dipped and the porch above them grew cold. The light through the boards dimmed, and the laughter that once filled the space turned to silence. Henry didn’t know it yet, but the first secret had already changed them both. Henry followed his father everywhere that week. It was expected the son of the master had to observe to learn the rhythm of power.

Robert Caldwell said a man couldn’t rule unless he understood the cost of obedience. Henry didn’t know what that meant, but he was about to find out. The air that afternoon was heavy with dust and the smell of burnt sugar.

From the back porch, Henry watched his father ride out to the edge of the fields where a group of men were gathered. One of them, an older man with a bent back and gray hair, stood apart, his wrists bound. Henry trailed behind, boots crunching through dry grass. His father glanced back once, but didn’t tell him to leave. That was permission enough.

Samuel,” Robert said evenly, dismounting his horse. “You were told not to talk back to Mr. Green, and yet he says you called him a liar.” The old man’s voice shook. “I only said the weight weren’t fair, sir.” The scales tilt. Robert smiled thinly, as if amused by the misunderstanding of a child. “And who decides what’s fair on this land, Samuel?” Samuel bowed his head.

“You do, sir.” “Good.” Robert nodded to the overseer. Then let’s remind you. The whip cracked once, sharp, clean, cruy efficient. Henry flinched despite himself. His father didn’t. He folded his arms and continued speaking in the same calm tone he used at supper. Henry, he said over the sound of the next strike, “You see, punishment isn’t anger. It’s correction.

A man must separate his feelings from his duty. If he enjoys it, he’s a brute. If he avoids it, he’s weak. Henry nodded, though his throat felt tight. The whip cracked again. Samuel stumbled forward, catching himself before falling. His face twisted, but he didn’t cry out. His silence felt heavier than the sound. Robert turned slightly.

Discipline keeps peace. Without it, everything collapses. Henry looked at the other workers, their heads bowed, still as statues. He wondered if they were afraid of the whip or of his father’s quiet voice. When it was over, Samuel was released. Robert took his gloves off, brushing away invisible dust, and looked down at his son.

“A man earns respect not by shouting, but by deciding what must be done and doing it without hesitation.” “Do you understand?” Henry whispered. “Yes, sir.” “Good,” his father said, mounting his horse. One day this will all be yours. Learn what it means to hold order and never let your heart soften for it. That night Henry lay awake, staring at the ceiling.

The sound of the whip echoed in his memory. Not the strike, but the silence after. He thought of Isaac somewhere out there under the same sky, and wondered if he’d seen. In the dark, Henry pressed his palms together and prayed for forgiveness, though he didn’t know whose forgiveness he needed more, Samuels or his fathers.

The next morning, the plantation felt quieter. Even the air seemed cautious. Henry noticed how the workers avoided the main path, keeping their eyes down. His father’s lesson from the day before lingered in the air, not as sound, but as behavior.

Henry carried a small basket from the kitchen that afternoon filled with the scraps his mother always left untouched. Biscuits gone cold, a slice of apple pie, a few pieces of salted pork. He told himself it was for the dogs, but his steps led him toward the stables instead. Isaac was there sweeping the dirt floor. His shirt clung to his shoulders with sweat. When he looked up, Henry lifted the basket.

I brought you something, he said. Isaac straightened, wary. For me? Don’t act surprised, Henry said quickly, though he wanted Isaac to be. You’ve worked hard. Isaac hesitated. If I take it, I get in trouble. Henry shrugged. No one has to know. He set the basket down and waited. Isaac took a small piece of bread, eating it slowly like he wasn’t sure it was real.

Henry watched every bite, a strange warmth swelling in his chest, power that felt almost holy. “You should say thank you,” Henry said softly. Isaac wiped his hands. “Thank you, Master Henry.” Henry nodded, feeling the words settle into him like approval. “You’re welcome.” He wanted to tell him not to say master, but something stopped him. The title made him feel older, important.

The more Isaac said it, the more right it began to sound. A moment later, a voice called from outside. Henry froze. It was his father’s tone. Low, calm, dangerous. “Henry, you out here?” “Yes, sir,” Henry shouted back, stepping quickly away from the basket.

Robert Caldwell appeared in the doorway, his shadow long and sharp across the hay. “What are you doing?” “Feeding the dogs, sir,” Henry lied. Robert’s gaze flicked to the basket. The bread was gone. He looked at Isaac, who had gone still, his hands folded tight. “You should be careful who you feed,” Robert said. “Mercy is a gift that spoils quickly.

” Henry felt the back of his neck prickle. “Yes, sir.” His father smiled faintly, resting a hand on his shoulder. “Kindness isn’t free, Henry. Every good deed must remind the lesser man who allows it.” He squeezed once, hard enough to hurt. Do you understand? Henry swallowed. Yes, sir. When his father left, the air felt thinner.

Isaac was still watching him, not angry, not afraid, just disappointed. That look pierced deeper than any whip could. Henry tried to speak, but nothing came. He only nodded, the words, “You’re welcome,” echoing back in his head like a curse. Later, when he lay in bed, he whispered to himself what his father had said. “Mercy is a gift that spoils.

” He tried to believe it, but the image of Isaac’s eyes, tired, quiet, human, kept breaking the spell. The following week, Henry’s father called him into the study. The air in that room was always still, thick with tobacco and leather polish, heavy with the scent of authority. The late afternoon light sliced through the blinds, laying stripes across the floor like bars.

Robert Caldwell sat behind his desk, turning something over in his palm. When Henry entered, he gestured for him to come closer. “Do you know what this is?” his father asked, holding up a small brass key. “Henry shook his head.” “It’s yours,” his father said, placing it in his hand. The metal was warm, smooth from years of use.

“It opens the shed by the carriage house. That’s where the supplies are kept. Nails, rope, oil, tools. From now on, it’s your responsibility to see that it stays in order. Henry’s chest swelled with pride. Yes, sir. Robert smiled faintly. You’ll learn something important about command there. Ownership isn’t just about having. It’s about keeping others in their place while you do.

Henry nodded, clutching the key. The weight of it felt strange, heavier than it should have been. That evening he went to the shed alone. The door creaked open and the air inside smelled of iron and dust. Lanterns hung on the walls and shelves were lined with tools. At the back, two boys were sweeping. One of them was Isaac.

He looked up when Henry entered, his brow damp with sweat. “We ain’t done yet,” Isaac said softly. Henry held up the key, feeling its edges press into his palm. It’s my job now to make sure everything’s right. Isaac nodded, returning to his sweeping. The other boy, smaller, quieter, kept his head down. Henry walked the aisles, pretending to inspect the tools.

“You missed a spot,” he said, pointing toward a pile of sawdust in the corner. Isaac brushed it up immediately. “Yes, sir.” The sir hit different this time. It didn’t sound fearful, just practiced, natural. Henry didn’t know whether to feel proud or ashamed. He lingered a moment longer, watching Isaac work. When the boy straightened, wiping his forehead, Henry said, “You can go now.

” “I’ll finish here,” Isaac hesitated. “Master Caldwell said not to leave till I’ll tell him I said so.” Henry interrupted. Isaac looked at him for a moment, then nodded. “Thank you, Master Henry. As he left, the words echoed through the dim shed. Master Henry. Henry stood there alone, the dust swirling in the slanted light. He ran his fingers over the key again. It no longer felt warm.

It felt cold, like something taken from the ground. When he locked the shed door behind him, he didn’t realize the sound it made. That hard click would stay in his head for years. He told himself it was learning responsibility. But somewhere inside another word was growing.

Quieter, heavier, more permanent ownership. The house felt quieter now, though nothing had truly changed. The cicadas still sang, the servants still whispered, and Henry’s father’s footsteps still carried that same rhythm of control. Yet to Henry, something in the air seemed softer, like it was holding its breath. his mother had been taking to her bed more often.

The doctor came twice a week, always leaving with his hat in hand, and pity in his eyes. When Henry entered her room that evening, she was half sitting against her pillows, a thin blanket drawn to her chest. The window was open, letting in the sound of frogs from the marsh beyond. “Henry,” she said, smiling faintly. “Come sit.” He obeyed, taking her pale hand in his.

It felt cool, fragile. Father says you’ll be well soon. Her smile flickered. Your father likes to believe his words can make truth of anything. She brushed a strand of hair from his face. But I know he’s teaching you more than your lessons, isn’t he? Henry looked down. He says I have to learn how to be strong. Her gaze sharpened, gentle but steady.

And what does he call strong? Not flinching, Henry said. Not letting your heart change your duty. She closed her eyes. Ah. The same poison poured into a new glass. He frowned. You shouldn’t say that, mama. He. She squeezed his hand. Hush. I’ve said nothing wrong. A silence stretched between them, filled with the hum of the night. Then faintly she began to hum.

A melody Henry didn’t know. It was soft, low, like something meant to comfort a baby. “What song is that?” he asked. “A lullabi,” she said. “An old one. The woman who helped raise me used to sing it. Her name was Ruth. She knew songs that didn’t belong to the house, songs that belong to the earth.” Henry listened closely.

The tune was simple, but it felt alive, warmer than anything in the house, carrying a sadness that didn’t hurt to hear. When the song ended, he asked, “Can you teach me?” She smiled weakly. “You wouldn’t remember it, right?” “But maybe Isaac knows it. The name startled him.” “You know Isaac?” “Of course,” she said softly. “He brings me tea when I can’t sleep.” “He’s kind.

You should be kind to him, Henry. Not the way your father means it. The other way. What other way? The kind that costs you something, she whispered. That night, Henry sat by his window, the brass key to the shed still in his pocket, heavy and cold. He hummed the lullaby under his breath, trying to remember the tune.

From somewhere outside, faint and distant, he thought he heard someone else humming the same song. He didn’t know if it was Isaac or just the wind carrying his mother’s voice away. Either way, he didn’t sleep. The morning broke heavy with heat and silence, that suffocating stillness that came before something cruel. From the porch, Henry watched the fields shimmer under the sun.

The overseer’s shouts carried faintly on the wind, but no one answered. Even the cicadas were quiet. By noon, the stillness cracked. A commotion rose near the main road, the sharp ring of a man’s voice cutting through the air. Henry stepped down from the porch steps before anyone could stop him. He followed the sound toward the fields until he saw the source.

His father standing tall beside a horse, a riding crop resting loosely in his hand. Isaac knelt in the dirt at his feet. The sight made Henry’s stomach twist. His shirt was torn, his back stre with dust and sweat. The overseer stood nearby holding a half loaf of bread. He was caught taking it from the kitchen.

The overseer said it was for one of the children who missed supper. Robert Caldwell didn’t look angry. He looked bored. The kind of calm that always frightened Henry more than shouting ever could. Is that true, Isaac? His father asked, voice smooth. Isaac didn’t raise his head. Yes, sir. Robert sighed as though disappointed by poor manners rather than theft.

Stealing is theft of order, not food. If a man can’t follow rules, he’s no better than the beast that feeds without permission. He turned to Henry. A lesson, son. Come here. Henry hesitated. Father, come here. When he obeyed, his father placed the riding crop in his hand. The leather was warm from the sun.

If you want to be a man, you’ll understand this. Mercy must be earned. Isaac’s learned enough words to know right from wrong. You give him correction or you tell me you’ve learned nothing. Henry’s heart pounded. I can’t, he whispered. Robert crouched beside him, his voice softened, almost kind. Yes, you can. You must. Isaac lifted his eyes then.

There was no anger there, just quiet understanding. He nodded once almost imperceptibly. It’s all right, Master Henry. Henry’s throat tightened. His hands trembled around the crop. The moment stretched thin, the whole world waiting for a sound. When the crack came, it was smaller than Henry expected. Quick, final. Isaac didn’t cry out.

He only closed his eyes. Robert placed a hand on Henry’s shoulder. There, he said, “You’ve done what’s right. A man who hesitates invites chaos.” Henry’s hand went numb. He dropped the crop and stumbled backward. That night, he washed the dirt from his hands until they burned. The sound of the leather still lived in his ears. He told himself it was duty, that he’d done what was required.

But every time he closed his eyes, he saw Isaac’s calm, steady, forgiving, and it made the word mercy feel like something sharp. That night, the house was filled with laughter. Guests had come for supper, plantation owners, merchants, and their wives. Crystal glasses clinkedked, silverware chimed, and the chandelier cast its golden light over polished faces, pretending the world outside did not exist.

Henry sat quietly beside his mother, pushing his food around the plate. The sound of his father’s voice rose above the others, warm, charming, confident. It was the same voice Henry had heard that morning in the fields when he’d handed him the riding crop. The sound made Henry’s stomach turn. He excused himself early, claiming tiredness.

His mother’s hand brushed his cheek, a soft, wordless blessing. He left before his father could stop him. Outside the air was damp with the coming rain. Lanterns glowed along the path like small flickering ghosts. He followed them toward the quarters, his heart thudding with every step. When he reached the small cabin near the edge of the field, he saw the dim light of a candle inside.

Isaac sat by the wall, his shirt removed, a strip of cloth wrapped around his shoulder. Another boy was tending the wound. An older one, his hands gentle and practiced. When Henry appeared in the doorway, both boys froze. “I just wanted to see,” Henry said quickly to make sure. Isaac looked at him, the same calm in his eyes as before. I’m fine, Master Henry.

Henry stepped inside, ignoring the title. The air smelled of smoke and earth and blood. He set a small tin of ointment down beside Isaac. For the cut, he murmured. The older boy hesitated. “If they see you here, I said it’s fine,” Henry snapped, surprising even himself. Isaac reached out and placed a hand on his arm. “It’s all right,” he said softly. I’m all right.

The words should have soothed him. They didn’t. Henry’s throat achd. Why did you do it? Why take the bread? Isaac smiled faintly. Because somebody was hungry. That’s not reason enough to It was to me. Henry wanted to say something kind, but everything that came to his tongue felt wrong. You shouldn’t let him see you like that again, he said instead.

Isaac’s smile faded. You mean your father? Henry hesitated. I mean anyone? Isaac nodded slowly. Yes, sir. Henry looked at him then. Really looked. The candle light flickered over his face, soft and human, and the sight hurt. He wanted Isaac to forgive him, to smile the way he used to under the porch, to look at him like a friend again.

But when Isaac’s eyes met his, they held no anger, no warmth, just quiet distance. Henry whispered, “I’m sorry.” Isaac didn’t answer. He only blew out the candle. Henry stood there a moment in the dark, the sound of his own breathing loud in his ears. Then he left, clutching the guilt that felt too much like affection, heavy, twisted, and alive.

The next week the house was alive with preparations again. Another dinner, another performance. Palmetto Hill was a stage and every meal a sermon on order. Henry’s father stood before the mirror in his study, adjusting his crevat. Tonight, he said, you’ll show our guests what kind of boy you’re becoming.

Manners reveal breeding, but restraint proves command. Henry nodded. His reflection looked small beside his father’s, a miniature image, dressed in the same crisp white shirt, the same sllicked hair. He wondered if one day he’d even sound like him. When the guests arrived, the parlor filled with chatter and the sweet heavy scent of magnolia blossoms.

The men spoke of weather and cotton yields, the women of sermons and silk. Henry sat between them all, quiet, listening to how laughter could sound sharp if you knew what to hear. Halfway through dinner, Robert Caldwell raised his hand. “Bring in the boy,” he said to one of the servants. Moments later, Isaac entered the room. His clothes were clean, his face expressionless.

Henry felt his chest tighten. “Henry,” his father said, “I think our guests would like to see how well you keep your house in order.” The table fell quiet. Henry looked to his mother, but she kept her eyes on her plate. his father continued. “Tell the boy what to do.” Henry froze. His mouth went dry. “Sir, go on,” his father said gently, smiling for the guests.

“Ask him to serve you kindly, of course. Politeness is the armor of a gentleman,” Henry turned toward Isaac. Their eyes met for the first time since that night in the cabin. “Pour the wine,” he said softly. Isaac nodded and obeyed. His hands were steady, his gaze lowered. The dark red liquid filled Henry’s glass, and for a moment, Henry thought of blood.

When Isaac stepped back, Henry’s father said, “Good. Now, thank him,” Henry did. The room erupted in soft, approving laughter. Robert leaned back, pleased. “You see, grace and discipline. The balance of a good man,” Henry felt every heartbeat as if it might shatter his ribs. The guests raised their glasses. To young Master Henry, one man toasted. He’ll make his father proud.

The boy smiled because that was what was expected. But when he looked across the table, he caught Isaac’s reflection in the silver serving tray, eyes still and unreadable. Something twisted inside him. Then shame, pride, confusion. They tangled together until he couldn’t tell one from the other. His father raised his glass again.

To mercy, he said, the mark of civilized men. Everyone drank. Henry did too, his throat burning as the wine slid down. Across the room, Isaac slipped quietly back into the hallway, unseen, forgotten, except by the boy who had just thanked him for being invisible. That night, Henry dreamed of a dinner table that stretched endlessly, lined with smiling faces, and at the far end sat Isaac, serving himself.

The storm arrived without warning, a black curtain rolling over the sky, swallowing the last of the light. By nightfall, the magnolia trees bent under the wind, their blossoms torn and scattered across the ver like pale ghosts. Inside the house, lanterns flickered as thunder trembled through the floorboards.

Henry sat near the window, counting seconds between flashes of lightning and the deep, shaking roar that followed. His mother lay asleep in her room, her fever rising again. His father was in the parlor, calm as ever, reading a ledger by candle light. When the wind grew strong enough to rattle the shutters, Henry slipped out into the hallway.

The house felt alive, groaning, whispering, as if it too feared what was coming. He stepped outside, ignoring the rain that immediately soaked his shirt. He didn’t know what he was looking for until he saw movement near the stables. A figure running through the downpour. Small, fast, barefoot. Isaac.

Lightning flashed, catching his outline in white for half a second. He was crouched by the fence, struggling to lift something. A small animal, limp and trembling, caught beneath a fallen beam. Henry ran toward him. Isaac, he shouted over the storm. What are you doing? Isaac didn’t stop. It’s hurt, he said, voice straining against the wind. Can’t leave it. Henry looked back toward the house.

Through the sheets of rain, he saw the faint glow of his father’s candle light in the parlor window. He imagined that cold gaze finding them. “You’ll get caught,” he warned. Isaac lifted the broken fence just enough for the animal, a small hound, to crawl free. The moment it limped away into the darkness, lightning split the sky, blinding white.

Henry saw his father’s shadow appear behind the parlor window. Inside, Henry hissed. Now they ran toward the porch, boots slipping in the mud. When they reached the door, Henry pushed Isaac ahead of him and whispered, “Go back to your quarters. I’ll shut it.” But when Henry turned, his father was already standing in the doorway, calm, dry, silent.

“Open doors invite chaos,” Robert Caldwell said, voice low. Henry swallowed hard. I I opened it, sir. I forgot to close it after checking the shutters. Robert’s eyes flicked past him to the muddy footprints on the floor, small and bare. He said nothing for a long time. Then, with that same smile he wore when discussing discipline, he said, “Carelessness is worse than defiance.

It looks like mercy, but smells like rot.” “Yes, sir,” Henry whispered. “Clean the floor before you sleep,” his father said, and walked away. Henry stood there trembling, rain still dripping from his hair. Behind him, Isaac’s footprints were already fading into the dark grain of the wood. He closed the door, locking it tight, his fingers shaking on the brass handle. The sound of the wind outside felt almost like laughter.

That night, the storm passed, but its silence afterward was worse. The morning after the storm, Palmetto Hill glistened beneath the sun as though nothing had ever happened. The magnolia blossoms lay scattered across the grass, and the wet earth steamed in the heat.

The smell of rain had already turned back to the smell of soil and sweat. Henry sat on the steps of the porch, polishing his muddy boots. His stomach twisted every time he looked at the door he had lied about. He could still feel his father’s gaze from the night before, the way it seemed to see through him, not angry, just measuring.

When his father finally emerged from the house, he was in his riding coat, gloves folded neatly in his hand. “You lied well,” he said simply, not even as a question. “Henry froze.” “Sir.” Robert Caldwell smiled faintly. “You told me you forgot to close the door. You didn’t. You were covering for the boy Henry’s breath caught.

” “I don’t lie now,” his father interrupted. His tone was gentle, almost amused. If you’re going to deceive, at least do it once. Don’t waste the effort by pretending twice. Henry looked down. Yes, sir. Robert sat beside him on the step, his boots still spotless despite the mud.

A man who lies to protect chaos is a coward, but a man who lies to preserve order. That’s strategy. He tapped a gloved finger against Henry’s chest. You chose the right moment. You protected the illusion. That’s how the world stays steady. Henry said nothing. He wanted to ask if mercy could be a kind of lie, too. Instead, he whispered, Isaac didn’t mean harm. I know, Robert said calmly. That’s what makes it dangerous.

Softness spreads faster than rebellion. You’ll learn that. Someday you’ll thank me. He rose to his feet, brushing imaginary dust from his sleeve. Now go fetch your horse. We’ll ride the grounds before the soil dries. Henry obeyed, but his hands trembled as he saddled the mayor.

His father rode ahead, surveying the fields with pride, waving to workers who straightened when he passed. Henry followed behind, watching the bowed heads, the forced stillness. When they returned to the stables, his father dismounted and placed a hand on Henry’s shoulder. I’m proud of you, he said.

Most boys your age still think truth is a virtue. You’re learning that truth is a tool. Some truths destroy more than lies ever could. Henry nodded because it was expected. The praise burned colder than punishment. That evening he found Isaac sweeping the barn. Their eyes met briefly. Isaac’s calm. Henry’s uneasy. He wanted to tell him, “I saved you.

” He wanted Isaac to say thank you. but neither spoke. As Henry turned to leave, his father’s voice echoed again in his head. I’m proud of you. He wondered why it felt like a bruise. After the storm, Isaac changed. He still appeared where he was expected, in the fields, in the stables, carrying water to the house. But something about him had gone still.

The laughter that once lived in his voice was gone, replaced by a quiet that stretched over everything he touched. Henry noticed it immediately. He waited by the stables, by the well, even under the porch where they used to play. But Isaac never came. When their eyes met across the yard, Isaac looked through him, not in anger, not in defiance, but in absence, as if Henry had become invisible. At first Henry told himself it didn’t matter.

He had duties, lessons, and the endless sermons of his father to occupy him. But in truth, he felt the absence like hunger. One afternoon, he saw Isaac helping a younger boy carry a sack of corn. The boy tripped, spilling half of it onto the dirt. The overseer’s shout cut through the air like a whip itself, and Isaac instinctively stepped in front of the child.

Henry flinched, waiting for punishment, but none came. The overseer only glared and walked on. Isaac knelt to help gather the corn. His hands moved quickly, his head down. Henry watched from the porch, feeling an ache that had no name. He didn’t know if it was shame or jealousy, only that it burned.

That evening he carried a small wooden toy to the quarters, a horse he’d carved himself. He waited until the sun dropped low, and the fields turned bronze before knocking softly on the cabin door. Isaac opened it halfway, the light behind him dim. “I made this,” Henry said, holding out the toy. “For you.” Isaac looked at it, but didn’t take it. “You shouldn’t be here.” “I wanted to talk,” Henry pressed.

“There’s nothing to talk about.” Henry’s chest tightened. “You’re angry.” Isaac’s voice was calm. “I don’t have time to be angry, Master Henry.” The title stung worse than it ever had. Henry lowered the toy. I saved you that night. I lied for you. Isaac’s gaze lifted then, sharp and steady. You saved yourself. The words cut clean and quiet. Henry tried to speak, but his mouth felt dry.

Finally, he whispered. We were friends. Isaac’s eyes softened just a fraction. We were, he said, before you learned how to be like him. Then he closed the door. Henry stood there in the fading light, the toy horse still in his hand. The world felt smaller, as if even the air around him had turned away. When he returned to the house, his father was waiting on the porch.

“Good evening, son,” Robert said, his smile as polite as always. “You look like a man who’s beginning to understand loss.” It’s a useful lesson, Henry said nothing. But that night, for the first time, he dreamed of Isaac’s silence, and woke to find it still in the room with him. Henry couldn’t stand the quiet anymore.

Everywhere he went, Isaac’s absence followed, not as sound, but as an ache in the air. Even the magnolia trees seemed to whisper softer now, as if afraid to be heard. One evening, when the sun slipped behind the fields and the sky turned copper, Henry saw Isaac walking down the path beyond the stables. He wasn’t carrying tools or water. He was walking fast, his posture low, glancing over his shoulder. Henry waited until he was sure no one was watching, then followed.

The path led deep into the woods, where the smell of the river thickened in the air, mud, water, and wild mint. The sound of frogs echoed, broken by something else. Voices, dozens of them, soft and rhythmic, rising and falling like the wind. Henry crept closer until he saw the flicker of a small fire near the riverbank. A circle of men, women, and children stood around it, heads bowed.

Some swayed gently, some whispered prayers. Others sang, “Low, mournful, and beautiful.” Isaac stood near the edge, his face turned toward the flames, his voice blended into the others, steady and sure. Henry crouched behind a tree, his breath caught in his throat. He didn’t understand the words, but he felt them.

The way the sound wrapped around the night like a promise. It wasn’t rebellion. It wasn’t anger. It was grief turned into hope. For a moment, Henry forgot where he was. He forgot what he was supposed to be. Then someone whispered near him, “Who’s there?” A branch cracked beneath his foot, heads turned. The singing stopped. Isaac saw him. His eyes widened, not in fear, but in warning.

He stepped forward quickly, hands raised toward the others. “It’s all right,” he said. “It’s just me.” Henry stepped out from the shadows, his heart hammering. “I I was only walking,” he stammered. I didn’t mean. Isaac grabbed his arm and pulled him aside. You can’t be here, he hissed. If they find out.

I just wanted to see, Henry whispered. You were gone. I thought this ain’t for you, Isaac said, voice low but fierce. You ain’t supposed to hear these prayers. Henry’s face burned. Why? You think I don’t understand. Isaac’s eyes held his steady and sorrowful. because they’re not prayers for you. The fire popped, sending sparks into the dark.

The others had begun to sing again, softer now, the melody trembling like a secret. Henry looked at Isaac. Really looked. The boy who once played under the porch with him now seemed older, carved out of something stronger, something untouchable. Henry wanted to stay, but the weight in Isaac’s voice left no room for argument.

Go home, Master Henry,” Isaac said quietly. “You don’t belong here.” Henry walked back alone, the sound of the river song echoing behind him, a song that made him feel for the first time like the world could exist without him. Henry couldn’t stop thinking about the river.

The fire light, the songs, the way Isaac’s voice carried through the trees like something holy. It haunted him, not as guilt, but as longing. He wanted to understand what that prayer meant, why it made him feel so small. The next morning, while his father rode into town, Henry filled a small tin jug with clean water and carried it toward the river.

He imagined the look on Isaac’s face when he saw it. Gratitude, maybe forgiveness. That’s what he wanted most now, to be forgiven. When he reached the edge of the woods, he waited until the others left their work in the fields. Then he found Isaac near the old treeine, kneeling to tie a basket of herbs. I brought this for you, Henry said, holding the jug out.

Isaac straightened slowly, eyes narrowing. What for? You sang last night, Henry said quietly. I heard you. You shouldn’t be thirsty after praying. Isaac’s expression shifted. Not surprise, not gratitude. Fear. You were there? Henry nodded, expecting thanks. I won’t tell. But Isaac stepped closer, his voice sharp in a whisper. You can’t be near there, Henry. You don’t know what you saw.

If they find out, we gather. I said I won’t tell. You shouldn’t have been watching. Henry’s face burned. I was only trying to help. Isaac shook his head. That’s what your help always does. The words stung worse than any insult. Henry turned, gripping the jug until his knuckles whitened. “You’ll see,” he said. “I’ll make it right.

” He left before Isaac could answer. But that night Henry’s father called him into the study. The overseer stood there too, hat in hand, looking nervous. On the desk lay the jug Henry had brought to the river, mud still clinging to its side. Robert’s voice was calm. You left this near the woods? Henry’s mouth went dry. Yes, sir.

Why? I I thought someone might need it. someone. His father’s tone softened dangerously. You mean them? Henry hesitated. They were only singing. His father’s smile didn’t reach his eyes. They’re not supposed to gather after dark. And you’ve told me this now, haven’t you? Henry froze. He hadn’t meant to tell.

The truth had slipped out like a wound opening. Robert turned to the overseer. see that it’s handled. The man nodded and left. Henry’s stomach dropped. Father, please. Robert knelt to his height, eyes cold but proud. This is what good men do, Henry. They protect order. You’ve done right. But Henry didn’t feel right. He felt hollow.

Later that night, from his window, he saw torch light flicker in the distance near the river. He thought he heard shouting, but the wind carried it away before he could be sure. When the lights disappeared, he told himself it was justice, but what he felt was love dying and guilt being born. Days passed before anyone spoke of the river.

No one said what had happened, not openly, but the silence itself was heavy enough to tell the truth. The air on Palmetto Hill carried something new now, something sour. People moved slower. Laughter vanished. Even the birds seemed to sing softer. Henry noticed that Isaac didn’t appear for several days. He asked his father once casually where the boy had gone. Robert only said, “Some lessons are best learned in the dark.” Henry didn’t ask again.

“A week later, his father summoned him to the verander.” “It’s time you took on more responsibility,” Robert said, leaning on his cane. “A man must begin practicing control while he’s young. You’ll oversee the children in the quarters for a few hours each afternoon. They’re unruly. It will be good practice. Henry’s chest swelled with confusion and pride.

You want me to teach them? Robert smiled faintly. No, son. You’ll manage them. There’s a difference. That afternoon Henry walked to the quarters, his stomach tight. The children gathered when they saw him coming, barefoot, dusty, wideeyed. He held the brass key to the shed in his pocket like a badge of authority. At first, he didn’t know what to do. He told them to line up.

Some did, some didn’t. When one little boy giggled, Henry felt the sharp sting of humiliation. That same feeling he’d seen in his father’s eyes when others disobeyed. “Quiet,” Henry said, but his voice shook. The giggling continued. He remembered his father’s words. “A man doesn’t shout. he commands.

So Henry smiled instead. Anyone who listens gets something sweet, he said. That worked. The children fell silent, obedient, curious. He handed out two sugar cubes from his pocket, small things his mother kept for her tea. The children smiled, their eyes bright. Henry felt a strange thrill. Not cruelty this time, but control. He learned quickly.

A frown could make them nervous. A kind tone could make them trust him again. Power wasn’t the whip. It was the rhythm between kindness and fear. When Isaac finally reappeared, thin and quiet, Henry was standing near the well, a cluster of children surrounding him. Their eyes flicked toward Isaac, but they didn’t speak. Isaac paused, then approached.

“You teaching now?” Henry shrugged. “Father says, I’m learning to lead.” Isaac looked at the children, their polite stillness, their folded hands. That what you call it? Henry stiffened. They’re happy. Happy don’t mean free, Isaac said softly. Henry’s jaw clenched. You think you know everything, don’t you? Isaac’s gaze stayed steady.

“No, but I know what it feels like when someone learns how to break you slow.” He turned and walked away. The words sank into Henry like stones. For the first time, he understood what his father meant when he said control wasn’t about noise. It was about silence that obeyed. That night, Henry couldn’t stop hearing Isaac’s voice. Break you slow.

He told himself it was just another lesson. But something inside him knew this one would never leave. The day after the torches by the river, the plantation heir felt like ash. No one spoke of what had happened. Not the overseer, not the house servants, not even his father. But Henry knew. He felt it in the strange quiet that hung over the land in the way even the birds refused to sing.

He saw Isaac again two days later. His right arm was bound in a strip of rough linen, and he walked with a limp. He was thinner, his face hollow, but his eyes still clear. Henry had never seen someone look both alive and gone at once. “Isaac,” Henry whispered when they crossed paths behind the stable. Isaac didn’t stop.

“I didn’t mean,” Isaac turned then, his voice a rasp. “You never mean it.” The words struck like a slap. “I was trying to help you,” Henry said desperate, stepping closer. “I thought if I told him, maybe what?” Isaac interrupted, his tone low and even. He’d show mercy. That word don’t live in him, Henry. It never did, Henry’s throat burned.

I didn’t know he’d send them there. Isaac’s eyes glinted in the sunlight. No, but you knew he’d do something, and you told him anyway. Henry wanted to scream that it wasn’t betrayal, that it wasn’t his fault, that he was trying to save Isaac from being found another way. But even in his own head, the words sounded thin.

Do you hate me?” he asked instead, barely above a whisper. Isaac looked at him for a long moment. Then he said quietly, “I don’t got time to hate you. You’ll do that for both of us.” He walked away. That night, Henry sat alone in his room, the brass key to the shed heavy in his palm.

He thought about what his father had always said, that a man must choose duty over weakness. He thought of Isaac’s arm, the cloth stained brown with dried blood. Something inside him cracked, not like a bone, but like a door. He went downstairs and found his father in the study writing letters by candle light. Father, Henry said, his voice trembling, but steady. If someone disobys and you forgive them, they’ll never respect you again, right? Robert looked up pleased. Exactly. So, Henry nodded slowly.

Then you have to make sure they remember who owns them. His father smiled, proud of the echo. Now you understand, my boy. Henry did understand. That was the horror of it. Later, when he saw Isaac again, he didn’t speak to him. He only stared long, hard, expressionless, the way his father would. Isaac met his gaze, unflinching, then turned away.

That night, Henry whispered into the darkness, “Mercy is dead.” He didn’t know if he was burying Isaac’s soul or his own. His mother’s death came quietly without the dignity his father’s sermons always promised. No thunder, no wailing, just one still mourning, sunlight spilling through the window, and her hand once so gentle, slipping from his.

The doctor said it was fever. The preacher said it was God’s will. But Henry knew better. It was sorrow that took her, the kind that sits in the body until it forgets how to breathe. Robert Caldwell buried her beneath the magnolia tree she had loved since girlhood. The roots had cracked the soil, and her white coffin looked like a pearl trapped in earth. The family gathered in silence.

The field hands stood far back, heads bowed, forbidden to come close. When the preacher spoke, Henry barely listened. His father’s hand rested on his shoulder, heavy and firm, the same way it always did. Not comfort, but possession. “Your mother was a good woman,” Robert said afterward, his tone polished, rehearsed. “Too gentle for this world.

” Henry wanted to scream that gentleness was what made her human. Instead, he nodded like a beautiful son. That night, the house felt different, too large, too bright. His father moved through it with mechanical calm, adjusting everything his wife had once touched, her chair, her books, the tiny vase of wilted flowers by her bedside.

He erased her as carefully as he had loved her. When he came to Henry’s room, his voice was steady, almost soft. “You’re the man of the house now,” he said. “Do you understand what that means?” Henry stared at the floor. “Yes, sir.

” Robert stepped closer, placing the same brass key, the one to the shed, in Henry’s hand again. “Then act like it. Your inheritance isn’t money or land. It’s control over yourself, over others, over what’s yours,” Henry swallowed hard. “Is that what you gave her, too?” For a moment, his father’s expression flickered. “Surprise, then warning.” “Your mother was happy,” he said coldly.

“She had everything she needed. She had you,” Henry said under his breath. Robert’s eyes sharpened. “Be careful, boy.” Words can make a man or hang him. When his father left, Henry sat on the edge of his bed, the key burning in his palm. He thought of his mother’s lullabi, the one she said Ruth had sung to her.

He hummed it softly, but it felt wrong now, hollow. Through the open window, the night wind stirred the magnolia branches. He thought of her beneath them. finally free of all this. And then he thought of Isaac, still alive, still bound by the same soil that had claimed her. He looked down at the key again, at the glint of brass in the moonlight.

He realized something, then inheritance wasn’t just what his father gave him. It was what he was trapped inside. And Henry began to wonder. If mercy could die, maybe love could, too. A month after the funeral, the plantation had resumed its rhythm. the cruel order of labor and silence. But inside the big house, something had shifted.

Robert Caldwell seemed more alive than ever, as if his wife’s death had freed him from restraint. He called Henry into the parlor one morning, his tone unusually warm. “You’ve grown, son,” he said. “I can see your mother in your eyes, and a good deal of me in your will. That’s a rare combination.” Henry stood stiffly. Compliments from his father always felt like traps.

Robert motioned toward the window where the field stretched wide beneath the rising sun. “You’ll oversee the harvest this week,” he said. “The men respect you.” “Let’s see if they fear you enough.” Henry’s pulse quickened. “You want me to give orders?” “I want you to keep order,” his father corrected. “It’s not the same thing.

” He handed Henry a ledger. its corners worn smooth by his own hands. Every number here must add up. If it doesn’t, someone’s to blame. The responsibility felt enormous and dangerous. Still, Henry nodded. Yes, sir. That afternoon, Henry walked the rows of the field under the relentless heat.

The workers glanced up briefly when he passed, then lowered their eyes. He carried the ledger tucked under his arm, the symbol of his father’s trust, or his father’s test. When he reached the far end of the field, he saw Isaac again, shoulders bent under the weight of a sack of grain. His arm was still wrapped, his movements slower now.

Henry hesitated, then said softly, “You shouldn’t be out here.” Isaac didn’t look up. Wasn’t given a choice. Henry opened the ledger, pretending to read it. If I tell him you’re still hurt, maybe he’ll let you rest. Isaac’s laugh was bitter, hollow. You telling him anything never ends well for me. Henry froze. The words stung, but he couldn’t argue.

You think I don’t care? Isaac wiped the sweat from his brow, caring, don’t fix what you break. A long silence stretched between them, the kind of silence that said everything words couldn’t. When the overseer approached, Henry snapped the ledger shut and stood taller. “He’s fine,” he said quickly before the man could ask.

“He can keep working.” The overseer nodded and moved on. Isaac stared at him, not angry, just tired. “You could have said the truth,” he murmured. Henry’s throat tightened. “I did,” he whispered, though they both knew it was a lie. That evening, when Henry returned to the house, his father was waiting by the door, sipping brandy. I saw you, Robert said.

You held your ground. You didn’t let sympathy cloud your duty. Henry’s stomach turned. Yes, sir. Robert smiled, proud. That’s my gift to you, Henry. The strength to do what must be done, even when it feels wrong. Henry nodded, but inside something in him recoiled because for the first time he realized his father didn’t see cruelty as failure. He saw it as love. and Henry feared he was beginning to understand why.

By midsummer Henry had become a fixture in the fields. The workers no longer looked up when he passed. They bowed their heads slightly, not in greeting, but in habit. The ledger, always tucked beneath his arm, had become his inheritance more than any land or title ever could. Each evening his father inspected the numbers, praising Henry for precision.

A man who can make the books sing, Robert Caldwell often said, can rule a world without lifting a hand. But Henry’s numbers didn’t sing. They lied quietly, carefully, and with intent. It began the day he saw Isaac stumble in the heat, the sun burning the bandage on his arm. The overseer wrote his name in the day’s log beside under quotota. Henry had read enough ledgers to know what that meant.

Half rations, doubled labor. That night, when he copied the entries into the official book, Henry wrote Isaac’s name again. Only this time he marked it as completed. It was a small rebellion, a whisper against a scream. For days, he continued. One by one he adjusted the totals, a basket added here, a number erased there.

Tiny acts of disobedience no one would notice. When his father reviewed the reports, he nodded approvingly. “You’ve got an honest hand,” he said. Henry nearly laughed at the irony. He began to notice things differently after that. The smallest tremors in the system his father called order. The way hunger made people slower. The way fear turned men into shadows of themselves.

The way mercy, when it appeared, seemed to startle even those receiving it. One afternoon, while reviewing figures by the well, Henry caught Isaac watching him. The boy didn’t speak, but when their eyes met, something wordless passed between them, a faint recognition. Henry looked down quickly, heart pounding. That night he erased three more penalties from the book.

For Isaac, for two others who worked beside him. It was foolish, reckless, and dangerous. Yet for the first time in months, Henry slept without hearing his father’s voice in his dreams. But peace doesn’t last long in a house built on control. A week later, his father called him into the study. The ledger lay open on the desk, the ink still fresh. Robert didn’t look angry. That made it worse.

Interesting, he said, tracing a finger down the page. It seems our yields have improved, even though the work pace hasn’t. How do you explain that? Henry’s heart stopped. I I don’t know, sir. His father smiled. Oh, I think you do. He closed the ledger softly. A good man must lie well, but never for the wrong side.

Henry stared at the book, his mouth dry, his pulse a drum beat. For the first time he saw what his father really loved, not him, not the land, but the illusion of control written in neat, obedient ink. And now that illusion was bleeding. The next morning the air in the house felt heavy. the kind of stillness that meant something was about to break. The servants moved quietly, eyes down.

Even the clocks seemed to tick slower. Henry ate breakfast alone. His father hadn’t joined him. The empty chair at the head of the table loomed like a question. When the butler appeared, his voice was subdued. Master Caldwell asks that you meet him at the barn. Henry’s fork slipped from his hand. He knew.

He didn’t know how, but he knew. The walk across the yard felt endless. The magnolia branches swayed in the wind, their petals dropping like pale tears. The barn door stood open, lantern light spilling out into the morning haze. Inside, his father stood beside the overseer. Isaac was there, too. His hands bound, his shirt torn at the shoulder. His face was expressionless, but his eyes were steady, almost calm.

Robert Caldwell spoke without turning. Henry, I’ve been thinking. You’ve learned much these past months, discipline, control, deception, but every man faces a moment when those lessons must be proven. He finally looked at his son. Do you know what this boy did? Henry’s voice trembled. No, sir. Stealing, Robert said.

A small thing. A loaf of bread again. But that’s not the sin. The sin is believing one can take without permission from me, from God, from order itself. Henry’s throat tightened. He was hungry. Then he should have worked harder. The overseer stepped forward, holding out the whip. The leather was dark, worn smooth by use. Robert gestured toward it.

You’ve lied for him before, haven’t you, Henry? Henry said nothing. Robert’s smile didn’t reach his eyes. I thought so. This time you’ll tell the truth, not with words, but with your hand. He pointed to Isaac. You’ll strike him three times, and you’ll do it because I said so. Henry’s breath caught. Father, please. Robert’s tone sharpened. If you can’t do this, you’re no son of mine. You’ll learn to rule or be ruled.

There’s no third kind of man. Isaac met Henry’s eyes. The calm there was unbearable. “It’s all right,” he said softly. “He’ll hurt you worse if you don’t.” Henry’s hands shook. The whip felt like a living thing, cold, coiled, waiting. Robert folded his arms. “Now.” The first crack barely touched the air.

Isaac didn’t flinch. The second tore through the silence. Henry’s vision blurred. When it was over, the whip fell from his hand. He couldn’t breathe. He couldn’t look at his father. Robert nodded, satisfied. “Now you understand, son. Leadership isn’t love. It’s sacrifice.

” He turned to leave, his boots echoing against the wood. Isaac, still kneeling, whispered through ragged breath, “You did what you had to.” Henry shook his head, tears burning down his face. “No,” he said. I did what he made me. And in that moment, something inside Henry broke. Not like glass, but like bone. It would heal. Yes, but wrong.

Forever wrong. Henry didn’t sleep that night. He sat in the dark of his room. The echoes of the barn still alive in his body, the sound of the whip, his father’s calm voice, Isaac’s silence. The candle beside him had burned down to its last inch, leaving streaks of wax across his desk. In its faint glow, he could see his reflection in the window.

A boy’s face that looked too much like a man’s, and a man’s eyes that looked too much like his father’s. He hated it. Outside, the magnolia branches scraped against the glass, whispering in the wind. Somewhere in the distance, thunder rumbled, though the sky was clear. When Henry rose from his bed, it wasn’t a decision. It was a movement, like a body remembering something it had already agreed to do.

He slipped out the back door, barefoot, the night air thick with the smell of dust and old rain. He found Isaac by the shed, sitting in the dirt, his head bowed. The rope marks on his wrists were still visible. When he looked up, there was no fear, just exhaustion, ancient and infinite. “You shouldn’t be here,” Isaac said softly.

I know, Henry whispered. But I can’t stay in that house. Not after, he stopped. Words felt useless now. Isaac studied him for a long moment. Then what are you going to do? Henry’s eyes shifted toward the mansion, its windows glowing faintly with lamplight. His father was likely in the study, writing figures in his ledger, shaping the world one neat line at a time.

something he can’t write out,” Henry said. Isaac’s expression changed. “Not shock, not approval, just a slow understanding.” “Fire don’t fix what men break,” he said. “Maybe not,” Henry said, “but it can stop them from using the pieces.” Before Isaac could answer, Henry turned and walked toward the house. The ground was dry, the wind rising. He moved like someone half asleep, half awake.

He didn’t feel fear, only a strange quiet clarity. He entered through the kitchen, found the oil lamp by the counter, and tipped it. The flame caught fast, hungry, bright. The curtains went first, then the tablecloth, then the walls. By the time he stepped outside, the fire had become a living thing. It roared against the sky, spilling light across the fields.

From the quarters, voices rose, shouts, screams, confusion. The house that had ruled them all for years was finally breaking apart. Plank by plank, window by window. Robert Caldwell burst through the door, shouting his son’s name. His voice was lost in the crackle. For the first time, Henry didn’t listen.

He turned toward the fields where Isaac stood watching, the orange glow flickering across his face. Their eyes met. Two boys bound by something older than either of them. The magnolia tree caught fire next. The blossoms turned black, their scent burning sweet and heavy in the wind. Henry whispered, “It’s over.” But Isaac, staring at the inferno, shook his head.

“No,” he said quietly. “It’s only just begun.” When dawn broke, Palmetto Hill was gone. The great house that once gleamed white under the sun now lay black and skeletal against the horizon. Smoke drifted lazily into the sky, turning the air thick and gray. The magnolia tree still stood, its branches stripped and charred, a few petals clinging stubbornly to life.

Henry sat in the mud near the edge of what had been the verander. His hands were black with soot, his clothes smelled of oil and smoke. He didn’t remember sleeping. He barely remembered breathing. No one spoke to him. The overseer and his men moved in silence, searching for what could be saved. Not people, but ledgers, silver, tools. The house was gone. Yet order demanded inventory.

Even in ruin, his father’s voice seemed to linger, whispering numbers in his head. Robert Caldwell’s body hadn’t been found yet. Some said he’d escaped into the woods. Others said he’d been swallowed by his own fire. Henry didn’t ask which was true. Both endings felt like punishment enough. Isaac found him there, seated among the ashes.

He was limping, his shirt torn, but his eyes were steady. He didn’t say Henry’s name, just stood, waiting. Henry finally spoke. I didn’t mean to kill him. Isaac crouched down beside him. Didn’t mean to save him either. Henry’s lip trembled. I thought it’d stop everything. Isaac looked out at the smoke rising from the ruins.

Ain’t no stopping it. Not yet. But maybe it won’t start again the same way. They sat there for a long time. Two figures in the ruins of a world that had built them both wrong. The fire had taken almost everything, but not silence. Not the river that ran behind the fields, carrying ashes and petals downstream.

By noon, the others began to leave, heading toward nearby plantations for shelter, for orders, for survival. No one told Isaac or Henry what to do. No one dared. Henry stood slowly, his legs weak. He looked at Isaac. What happens now? Isaac’s voice was soft. You got to live with it. I don’t know how. Isaac gave a small, tired smile. You’ll learn. It’s what we all do.

They walked toward the river together. The sky was pale and clean now, the first light of real morning breaking through the smoke. When they reached the bank, Henry knelt, cupping the water in his hands. It ran brown with ash. He watched it slip through his fingers.

Behind him, Isaac stood beneath the ruined magnolia tree, the wind lifting the soot from his hair like slow snow. “Isaac,” Henry said, his voice breaking. “If I could go back.” “You can’t,” Isaac said quietly. “But you can go forward different.” The words stayed with him even as the wind carried the last threads of smoke away.

Henry turned once more toward the blackened house, then away for good, and as they walked into the trees, the air smelled faintly, impossibly, of magnolia. Years passed. The land changed names, as land always does when its owners die or disappear. The ruins of Palmetto Hill were swallowed by weeds and vines, its bricks scattered by storms and time.

People said the fire had been an accident. Others said it was punishment. No one mentioned the boy who walked away from it. Henry never returned. He moved from town to town, always under a different name. Sometimes he worked with his hands. Sometimes he taught children their letters in dusty school rooms that smelled of chalk and rain.

He learned to live quietly without servants, without ledgers, without mirrors that reflected his father’s face back at him. But at night, when the wind rustled through the trees, he heard the crack of fire, and sometimes faintly the sound of a boy’s voice singing by a river. He grew older, but never hard.

The cruelty that had once been taught into his bones stayed there like a scar, but he no longer mistook it for strength. The world called him a kind man, but he knew better. Kindness was what you offered before the truth. What he carried now was something else, a quiet, steady grief that made him gentle. One spring he returned south. The river still ran wide and slow. The magnolia trees still bloomed white as ghosts.

He followed the old road until he reached the hill. The house was gone, just as memory had promised, but the magnolia tree stood tall again, grown wild, its roots deep and twisted through the charred foundation. Underneath it, someone had placed a simple wooden cross.

The letters were nearly faded, but he could still make out two words carved by an unsteady hand. Ruth Caldwell, his mother. Henry sank to his knees. The earth smelled like ash and rain. For a long while, he said nothing. Then he whispered, “I’m sorry.” The wind moved gently through the branches, scattering white petals around him. A sound came from the river. soft footsteps.

When he turned, he saw a man watching from the treeine. Older, broader now, but unmistakable. Isaac. Neither spoke for a long moment. Then Isaac said, “You came back.” Henry nodded. “I wanted to see if anything could grow here again.” Isaac’s gaze went to the magnolia tree. “Looks like it can.” Henry managed a small, tired smile.

Do you ever think about them all the time, Isaac said, but I don’t carry them anymore. Henry looked toward the burned horizon. I think I still do. Isaac placed a hand on his shoulder, steady, forgiving, human. Then put them down, Henry. The past already buried itself. The two men stood there as the light changed, the hill quiet and alive again.

For the first time in his life, Henry understood what his mother had meant when she said mercy was what kept a person human. He wasn’t his father’s son anymore. He wasn’t anyone’s master. Just a man who finally learned how to be good. And as he left Palmetto Hill for the last time, the Magnolia Petals fell behind him like snow, soft, white, and free. And so that was the story of the good son of Palmetto Hill, a boy born to rule, who learned too late that mercy costs more than power ever gives.

Some say the hill still smells faintly of smoke after rain. Others say if you stand by the river at dawn, you can hear two voices, one praying, one forgiving. Before you go, make sure you subscribe to the Maca Record, where forgotten truths and haunted histories breathe again.

and tell me in the comments what do you think mercy costs? A soul, a life, or just a choice made too late? Now let the hill

News

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load