The Forgotten Asylum Where Inbred Children Were Bred Again for Research.

In 1840, deep within the fog shrouded hills of rural Massachusetts, there existed an asylum that no map dared to mark. The Willowbrook Institute for the afflicted wasn’t built to heal the broken mind society discarded. It was built to use them. What began as whispers among terrified tidulos would eventually become the most disturbing chapter in American history.

One so grotesque that every record was burned, every witness silenced, and every victim erased from existence. But some truth refused to stay buried. This is the story of the forgotten asylum, where inbred children weren’t just studied. They were bred again and again and again in the name of research that would make even the devil recoil.

What you’re about to hear will challenge everything you think you know about the limits of human cruelty. Because the real horror wasn’t what they did to those children. It was why they did it and what they discovered in the process. The winter of 1840 arrived early in Milbrook County, Massachusetts. Bringing with it a cold so vicious it seemed to seep into the bones of the earth itself.

The villages of Clearwater, a settlement of barely 300 souls, huddled close to their fireplaces, and spoke in hush tones about the new institution that had appeared on Raven’s Peak, the highest and most isolated hill overlooking their town. They called it Willowbrook, though no willows grew anywhere near that cursed place.

The building rose from the rocky terrain like a malignant growth, all sharp angles and dark stone, its windows too narrow and too many, giving it the appearance of a massive insect watching the valley below with a thousand black eyes. Nobody in Clear Water remembered seeing it being built. One autumn morning, it simply wasn’t there, and by the next spring, it stood complete, as if it had always existed, waiting.

Dr. Sebastian Crowe arrived in Clear Water on a November evening when the fog was so thick that horses refused to climb the mountain road. He came alone driving a black carriage pulled by two gray mares that looked half starved, their ribs visible even through their matted coats.

The locals who saw him described a man of perhaps 40 years, tall and unnaturally thin, with hands that seemed too long for his arms and eyes that never quite focused on the person he was addressing. He wore a physician’s black coat that hung from his frame like a funeral shroud. And when he spoke, which was rarely, his voice had a quality that made people want to end the conversation as quickly as possible.

There was something wrong about Bro, something that existed just beneath the surface of his pale skin, and every animal in Clear Water seemed to sense it. Dogs would whimper and slink away when he passed. Horses would rear and fight their rain. Even the crows, those fearless scavengers, would fall silent when his shadow crossed their path. Dr. Crow wasted no time integrating himself into the community because he had no intention of doing so.

He visited the town exactly once, stopping at the general store owned by Thomas Brennan, a stout man with a red beard who prided himself on knowing everyone’s business. Brennan watched as Docro purchased an unusual assortment of items. 30 ft of heavy chain, multiple locks of varying sizes, 12 large mirrors, hundreds of candles, and stranger still, 20 leatherbound journals, and enough ink to fill them all several times over.

When Brennan, unable to contain his curiosity, asked what manner of institution Willoughbrook was, Dr. The crow turned those unsettling eyes upon him and replied in a voice devoid of warmth. A place of mercy for those the world has deemed unfit to live among the righteous. A sanctuary for the afflicted, Mr. Brennan.

Surely you understand the Christian duty of caring for the least among us. The words were proper enough, but the way he said them made Brennan’s blood run cold. There was no compassion in that voice, no hint of charitable intent. It was the voice of a man describing livestock, not human beings. Within two weeks of Dr. Crow’s arrival, the wagons began coming.

They arrived exclusively at night, always taking the eastern road that wound through the densest part of the forest, away from the villages prying eyes. But Clear Water was a small town, and secrets had a way of traveling faster than horses. Young Samuel Porter, the blacksmith apprentice, who was barely 16 and prone to sneaking out to meet his sweetheart, saw the first wagon.

He’d been coming back from Mary Fletcher’s farm, cutting through the woods to avoid being caught by his master when he heard the wheels creaking on the frozen road. Samuel pressed himself behind a massive oak tree, his heart hammering, expecting to see smugglers or fugitives. Instead, what he saw would haunt him for the rest of his short life.

The wagon was enclosed, its sides solid wood painted black with no windows except for small ventilation slits near the roof. It was pulled by four horses driven by two men in long coats who never spoke. But it was the sounds coming from inside the wagon that made Samuel’s bladder nearly release. children’s voices, perhaps a dozen or more, crying and calling out in tones that ranged from pleading to animalistic howling.

Some called for their mothers, others made sounds that no human throat should be able to produce. And underneath it all was a smell that drifted on the cold night air, a mixture of unwashed bodies, excrement, and something else, something sweet and rotten that Samuel couldn’t identify. He watched frozen in terror as the wagon passed within 20 ft of his hiding spot and continued up the mountain toward Willowbrook.

When it was gone, Samuel ran home faster than he’d ever run in his life. And when he burst into the blacksmith’s quarters, sobbing and trying to explain what he’d seen, his master, John Porter, dismissed it as imagination fueled by guilt over his nighttime wanderings.

But Samuel insisted, and the next morning, still shaken, he told his story to anyone who would listen. Most dismissed him as Mary Fletcher had finally driven him mad with her teasing. But a few older residents remembered something that made their weathered faces grow pale. 20 years earlier, there had been another institution in the next county over, a place called Riverside Home for Unfortunates, and it too had received nighttime deliveries.

That place had burned to the ground under mysterious circumstances, and the official report claimed all 20 residents had perished in the fire. But several people swore they’d seen wagons leaving in the night just before the flames consumed the building. Nobody knew where those wagons had gone, and nobody had been brave enough to ask.

The wagons continued to arrive throughout the winter, always at night, always taking the hidden eastern road. The villagers began to keep unofficial count. Three wagons in November, five in December, seven in January. Each one packed with cargo that wailed and screamed and made sounds that caused mothers to clutch their own children closer. Reverend Michael Ashford, who led the small Episcopal church in Clearwater, decided it was his Christian duty to visit Willowbrook and offer his services as spiritual counselor to whatever poor souls resided there. He made the climb on a February morning when the sun actually broke through the clouds, thinking perhaps God was blessing his charitable mission.

The road to Willowbrook was poorly maintained, more of a trail, really, winding through dead trees and over rocks that seemed deliberately placed to make the journey as difficult as possible.

It took Reverend Ashford nearly 3 hours to reach the gates, and when he finally stood before them, sweating despite the cold, he felt his resolve waver. The gates were rorought iron, 15 ft tall, decorated with designs that appeared religious at first glance, but revealed themselves to be something else entirely upon closer inspection. What he’d initially thought were angels were actually figures with too many limbs, their faces twisted in expressions that could be ecstasy or agony.

The crosses worked into the design were inverted in subtle ways, and the overall effect was deeply unsettling. Beyond the gates, the asylum itself loomed even larger than it had appeared from the valley. It was built in a severe Georgian style, three stories of dark gray stone with that multitude of narrow windows and absolutely no ornamentation except for a single inscription above the main entrance that Reverend Ashford couldn’t quite read from where he stood.

The grounds were barren, not a single plant or tree, just hardpacked earth and scattered rocks. No smoke rose from any chimney despite the bitter cold which struck the reverend as odd. Where were they getting heat? How were they cooking? He pulled the bell chain that hung beside the gate and somewhere deep within the building a bell told with a sound like a funeral durge.

He waited 5 minutes 10 15 He was about to pull the chain again when he heard footsteps approaching from inside. Not the normal footfalls of a person walking, but a strange shuffling, dragging sound, as if whoever approached was injured or deformed. The figure that emerged from the asylum’s front door and began crossing the baron yard toward him, made Reverend Ashford take an involuntary step backward. It was a woman, or had been one.

She wore what might have been a nurse’s uniform, but it was stained with substances the Reverend didn’t want to identify, and hung from her frame in tatters. Her hair was white despite her appearing to be no more than 30, and her face bore scars that formed patterns almost like white. But it was her eyes that truly disturbed him.

They were completely white, no iris or pupil visible, as if someone had taken a brush of white paint and covered them entirely. Yet she navigated the rocky ground with perfect confidence, never stumbling, walking directly toward him as if she could see him perfectly well. When she reached the gate, she stood there silently, making no move to open it, just staring at him with those impossible eyes. Reverend Ashford cleared his throat, trying to project an authority he didn’t feel. Good morning.

I’m Reverend Michael Ashford from the Clearwater Episcopal Church. I’ve come to offer my services to Dr. Crowe and to minister to the residents of this facility, if such services would be welcome.” The woman continued to stare for a long moment. Then her mouth opened, and what came out wasn’t quite a human voice.

It had the right words formed with human lips and tongue. But the tone was all wrong, too flat, too emotionless, like someone reciting lines they’d memorized but didn’t understand. Dr. Crow accepts no visitors. The residents require no ministering. Your presence disturbs the work. You should leave this place and not return.

This is mercy, Reverend. Do not mistake it for anything else. The hair on the back of Reverend Ashford’s neck stood up. There was a wrongness to this woman that transcended her appearance. She radiated something that made his most primitive instincts scream at him to run.

But he was a man of God, and he’d faced down fever and fire and grief. He wouldn’t be turned away by a peculiar servant. I insist on speaking with Dr. Crow directly. It’s highly irregular for an institution of this nature to operate without any spiritual guidance. These poor afflicted souls need. The woman’s hand shot through the bars of the gate with a speed that seemed impossible.

Her fingers, which he now noticed, were too long. Each joint slightly extended beyond normal human proportions, wrapping around his wrist with strength that made him cry out. Her face remained expressionless. those white eyes boring into him. And when she spoke again, her voice dropped even flatter, taking on a quality that resonated in his bones. The children have no souls, Reverend.

That is why they were chosen. That is why they are here. Docro’s work cannot be interrupted by superstitious interference. If you value your sanity and your life, you will walk back down this mountain and forget this place exists. There are things being done here that your limited human morati cannot comprehend. Things that must be done.

Now go. She released his wrist and stepped back from the gate, and Reverend Ashford found himself stumbling backward, his courage evaporating like morning mist. He turned and half walked, half ran back down the mountain path. And when he reached his church, he locked himself in his study and prayed for three hours straight. But the woman’s words haunted him.

The children have no souls. What kind of doctor would say such a thing? What kind of place was Willowbrook really? That night, as snow began to fall over Clearwater, Reverend Ashford made a decision that would doom them all. He would write to the governor’s office. He would contact the medical board in Boston. He would expose whatever dark work was happening on Raven’s Peak. Consequences be damned.

He pulled out his finest parchment and began to write by candle light, documenting everything he knew, everything Samuel Porter had witnessed all the strange occurrences that had plagued their town since the asylum’s arrival. He never finished the letter.

Sometime around midnight, as the snow fell harder, obscuring the world in white, Reverend Michael Ashford sat at his desk, and picked up his letter opener, a small silver blade shaped like a cross that had been a gift from his late wife. Without hesitation, without any visible change in his expression, he pressed the blade against his own throat and drew it across in one smooth motion.

He bled out over his unfinished letter, and when his housekeeper found him the next morning, frozen in the unheated study, his eyes were open and staring at the ceiling, and his lips were curved in a smile of pure terror. The letter, now stained with his blood, had three additional words written at the bottom in handwriting that was definitely not the reverends. They read simply, “They have no soul.“

The death of Reverend Ashford should have sparked outrage, should have brought investigators from Boston, should have at least prompted questions about the mysterious asylum on the hill. Instead, it seemed to cast a pile of silence over Clear Water that was almost supernatural in its completeness.

The official ruling was suicide brought on by melancholia, a common enough affliction that no one questioned it too deeply, even though everyone who had known the reverend insisted he’d been in perfectly sound spirits. His replacement, a younger minister named Father Douglas, who arrived from Connecticut, was warned by the church elders not to venture near Willowbrook under any circumstances.

Father Douglas, being practical and somewhat cowardly, readily agreed. The asylum became like a dark star around which the town orbited, always present, always exerting influence, but never directly observed or acknowledged. People stopped talking about it entirely, as if by mutual unspoken agreement.

And when travelers passed through asking about the building on the hill, locals would claim ignorance or change the subject with such obvious discomfort that most visitors didn’t press the issue. But there was one person in Clear Water who couldn’t let it go, couldn’t accept the silence, couldn’t stop thinking about those wagons full of crying children and what might be happening to them behind those Greystone walls.

Her name was Eleanor Frost, and she was perhaps the least likely person to become involved in something so dangerous. Elellanena was 23 years old, unmarried despite considerable pressure from her family, and worked as a school teacher in Clearwater’s single room schoolhouse. She was small and delicate in appearance, with orin hair she kept pinned in a severe bun, and green eyes that missed very little.

Her students loved her because she treated them as thinking beings rather than empty vessels to be filled with information and her colleagues tolerated her because she was competent enough that her occasional unconventional methods could be overlooked. What nobody knew about Eleanor Frost was that she had a secret that would have destroyed her reputation and livelihood if discovered.

She could read Latin, Greek, and German, had studied anatomy and natural philosophy through books she’d secretly borrowed from her late uncle’s library, and possessed an intellect that would have earned her a place at any university in the country, if she’d had the misfortune of being born male.

Eleanor had been 12 years old when her younger brother, Thomas, was born, and even at that age, she’d known something was terribly wrong with him. He’d emerged into the world, twisted, his spine curved at an unnatural angle. His legs folded beneath him in a way that no amount of the doctor’s manipulation could straighten. His head was slightly too large, and as he grew, it became apparent that his mind worked differently than other children’s.

He would scream at sounds no one else could hear, would become fixated on spinning objects for hours, could not bear to be touched without violent reaction. Their father, a prominent merchant, had hidden Thomas away in the attic rooms, telling neighbors the child had died in infancy. Eleanor had been the only one who truly cared for her brother, sneaking up to his rooms with food and books, talking to him even though he rarely responded, loving him despite his afflictions.

When Thomas was 7 years old, their father made arrangements for him to be taken away to an institution that promised to study and possibly cure children with such deformities and mental affliction. Elellanena had fought like a wild cat, screaming and clawing at the men who came to take Thomas, but she was only 19 and legally powerless.

They dragged her brother away while he shrieked in terror, and she’d never seen him again. Her father claimed Thomas had died six months later of a fever, but he’d never produced a body, never shown her a grave that had been four years ago, and the wound had never healed. So when Elellanar heard about Willougherbrook, when she listened to Samuel Porter’s terrified description of the wagons, when she saw how the entire town suddenly refused to acknowledge the asylum’s existence after Reverend Ashford’s convenient suicide, something clicked into place in her sharp minds. This was where they took the children that society wanted to forget. This was where Thomas might have ended up, or if not Thomas, then children just like him. And whatever was happening behind those walls, it was something so terrible that merely approaching the place could get you killed.

A sensible woman would have let it go, would have mourned privately, and moved on with her life. Eleanor Frost had never been particularly sensible. She began her investigation quietly, carefully, knowing that too much interest would draw exactly the kind of attention that had likely killed Reverend Ashford. She started by befriending Samuel Porter’s mother, bringing her fresh bread and helping her with mending, gradually steering conversations toward her son’s experience that night in the woods. Samuel himself had become increasingly withdrawn since seeing that wagon, jumping at shadows, and refusing to go anywhere alone after dark. His mother was worried sick about him, and Eleanor listened with patience and compassion while mentally cataloging every detail. She learned that Samuel had noticed something about the wagon he hadn’t mentioned in his initial panicked retelling.

There had been words painted on its side, partially obscured by mud, but still partially visible in the moonlight. He thought they said something like Riverside Transfer or Riverside Transport, though he couldn’t be certain. Elellaner’s heart had begun racing when she heard this river. That was the name of the institution that had supposedly burned down 20 years ago.

the one the old-timers whispered about. She visited the town’s elderly residents one by one, bringing them soup and medicine for their various ailments, and in the way of old people who are starved for company, they talked. She learned that Riverside Home for Unfortunates had been run by a doctor, Morai Crowe, and that this Doc Crow had a son who’d been training as a physician.

The dates lined up perfectly. Dr. Sebastian Crowe was continuing his father’s work, whatever that work had been. But what had they been doing at Riverside? The old-timers didn’t know or claimed not to know. But there were hints, strange sounds at night. Locals who got too close to the place, developing sudden illnesses.

A midwife who delivered twins with severe deformities was approached by Dr. Morai Crow himself, offering a substantial sum of money for the infants. The mother had refused, horrified. But 3 days later, both twins vanished from their cradle, and the mother went mad with grief, spending the rest of her short life in an asylum of a more conventional sort.

The more Eleanor learned, the more convinced she became that she needed to get inside Willowbrook somehow to see with her own eyes what was happening there. It was an insane notion, suicidal even. But once the idea took root, she couldn’t dislodge it. She began watching the asylum from a distance using a small brass telescope her uncle had left her, positioning herself on the roof of the schoolhouse after dark when no one would see her.

For 2 weeks, she watched, noting patterns. The strange white-eyed woman patrolled the grounds every night at 9:00 precisely, making a full circuit that took exactly 17 minutes. No lights ever appeared in the windows, which was bizarre for a building housing dozens of people. Once around 3:00 in the morning, she saw a group of figures emerge from the asylum and walked to the far edge of the property where they appeared to be digging. They dug for hours, and when they finally returned to the building just before dawn, they were no longer carrying the three large bundles they’d brought out with them. Elellanena had vomited over the edge of the schoolhouse roof, knowing with horrible certainty what had been in those bundle. They were burying children, children who had died from god knows what kind of treatment or experimentation.

This wasn’t a hospital or an asylum in any conventional sense. It was an abatatto. The night Ellaner decided to break into Willougherbrook was March 5th. She chose it because there was no moon, because a storm was rolling in from the east that would cover any sounds she made, and because she’d noticed that on Thursdays the white-eyed woman’s patrol was sometimes delayed, possibly due to other duties.

Elellanena dressed in her brother’s old clothes, dark trousers, and a heavy coat, and braided her hair tightly against her head. She brought a small bag containing a dark lantern, a notebook and pencil, a knife she had no idea if she could actually use, and a bottle of lordinum in case she needed to drug herself unconscious rather than let them take her alive.

She was terrified, her hands shaking so badly she could barely fasten the buttons of the coat, but she was also grimly determined. If children were dying in that place, someone needed to bear witness. Someone needed to document the truth. Even if that someone didn’t survive to tell it, she left a letter hidden in her room addressed to the governor’s office detailing everything she knew and everything she suspected.

If she didn’t return, perhaps eventually it would be found, and some form of justice might be done. The climb up Raven’s Peak in the dark during a rising storm was the most difficult thing Elellanena had ever done physically. The wind tore at her clothes and threatened to blow her off the narrow path.

Rain began falling halfway up, cold and hard as pebbles, soaking through her coat, and making the rocks slippery. Several times she fell, scraping her hands and knees, biting her lip to keep from crying out in pain and frustration. It took her nearly 2 hours to reach the gates, and by the time she crouched in the shadows beside them, she was shivering violently and beginning to question her sanity. The asylum looked even more forbidding up close in the storm.

Lightning occasionally illuminating its stark facade in flashes of white light that made it seem to pulse like a living thing. The gates were locked with a heavy chain, but Elellanena had anticipated this. The fence, though, could potentially be climbed at a point about 50 yards to the left, where the ground rose and the fence dipped slightly lower.

She made her way to this spot, the wind, now howling so loudly that she couldn’t hear anything else, which was both a blessing and a cur. Climbing the fence proved more difficult than she’d anticipated. The rot iron was slick with rain, and the decorative elements that should have served as handholds seemed designed to cut rather than help.

She tore her palms open on sharp edges, and felt something in her left shoulder pop painfully as she hauled herself over the top. The drop on the other side was longer than she’d expected, and she landed hard, the breath knocked from her lungs.

For several minutes, she just lay there in the mud, gasping and trying to regain her senses, while rain pelted down, and lightning continued its irregular illumination of the grounds. When she finally struggled to her feet, she realized she’d lost her bag in the fall. She searched frantically in the darkness, her hands groping through mud and rocks, until her fingers finally closed on the canvas strap.

Everything inside was soaked, but at least she still had her tools. She checked her pocket watch, which miraculously was still working. 9:05. If the white-eyed woman maintained her schedule, Elellanena had about 13 minutes before the next patrol. She needed to find a way inside immediately. The main entrance was obviously impossible.

But as Elellanena circled the building, staying close to the walls and trying to make herself as small as possible, she noticed something. There was a low door barely 4 ft high set into the foundation on the north side of the building. It looked like a coal shoot or root cellar entrance and more importantly it appeared to be slightly a jar.

She approached it carefully, every nerve screaming that this was a trap that nothing about this place would be left accidentally unsecured. But she had no choice. This was her only chance. She pulled the door open wider, wincing at the rusty shriek of hinges that thankfully was swallowed by the storm, and peered into darkness so complete it seemed solid.

The smell that wafted out made her gag and stumble backward. It was the stench of death and decay, of human waste, and something chemical, all mixed together into an assault on the senses that was almost physical. She pulled her coat collar up over her nose and mouth, lit her dark lantern with shaking hands, adjusted the shutter to let out only the barest sliver of light, and descended into the asylum.

The passage was narrow and low, forcing Elellanena to crouch as she moved forward, and the walls on either side were slick with moisture and something else, something that felt organic and wrong. She tried not to think about what she was touching. The passage sloped downward for what felt like 50 ft, then opened into a larger space. Elellanena widened the lantern’s shutter slightly, and immediately wished she hadn’t.

She was in a cellar that extended beneath the entire asylum, a vast space supported by stone columns, its floor covered in what appeared to be operating tables, at least two dozen of them, arranged in neat rows. But these were unlike any medical tables Eleanor had ever seen in her uncle’s anatomy books. They were fitted with leather restraints, multiple points, not just wrists and ankles, but also across the chest, thighs, and forehead.

Several had strange mechanical apparatus attached to them. Metal frameworks with adjustable arms ending in clamps and instruments whose purpose Eleanor couldn’t begin to guess. The tables themselves were stained with substances that ranged from brown to black, and the drains built into the floor beneath each one spoke to the regular need to wash away large quantities of liquid.

Eleanor moved between the tables, her lantern casting dancing shadows that made the metal instrument seemed to writhe, and tried to maintain the scientific detachment she’d need to document this horror. She pulled out her soap notebook and began sketching and writing. Her hand cramped and aching, but driven by desperate purpose.

Table one restraints show significant wear, particularly the forehead strap, suggesting violent resistance. Stains consistent with blood approximately 3 weeks old based on color. Mechanical apparatus appears designed for immobilizing the head while allowing access to cranium. Table two smaller dimensions designed for a child perhaps 6 to 8 years old.

Additional restraints around neck, possibly to prevent turning or speaking. Instruments nearby include what appear to be surgical sores, several different sizes. She moved from table to table, documenting everything. And with each new observation, the magnitude of what was happening here became more horrifyingly clear. This wasn’t medical treatment.

This was systematic vection performed on living subjects who were kept alive throughout procedures that should have killed them. At the far end of the cellar, Elellanena found what appeared to be a storage area, and what she discovered there nearly broke her entirely.

There were shelves floor to ceiling lined with glass jars, and in those jars, preserved in yellowish fluid, were specimens, human specimens. organs, certainly hearts and livers, and things she recognized from her anatomical studies, but also things she couldn’t identify, malformed growths, and impossible organs that didn’t match any human anatomy she’d ever seen.

And worse, far worse, were the jars containing whole specimens, infants, or things that had once been infants, preserved at various stages of development. Some looked almost normal except for extra limbs or missing features. Others were so deformed, so wrong in their construction that Elellanena’s mind struggled to process them as ever having been alive.

And the most disturbing detail, the one that made her drop her lantern and plunge the cellar into darkness for several terrifying seconds until she could retrieve it with trembling hands, was that many of these specimens had labels. Not medical labels with dates and descriptions, but names. Thomas Brinley expired March 3rd, 1841. Sarah Whitmore expired January 17th, 1841.

Marcus Chen expired November 29th, 1841. Elellanar forced herself to photograph the images in her mind, knowing her soap notebook could never adequately capture this nightmare. And then something made her freeze.

She heard footsteps above her, not the dragging shuffle of the white-eyed woman, but multiple sets of feet moving with purpose and voices, though she couldn’t make out the were. She quickly shuttered her lantern completely and pressed herself against the wall behind one of the support columns, her heart hammering so loudly she was certain they’d hear it. The footsteps moved directly above her, and then there was a terrible grinding sound.

stone moving against a section of the ceiling opened and a rectangle of dim light appeared. Someone was opening a trap door that led directly from the floor above into this cellar. Eleanor held her breath and prayed to a god she was no longer certain existed. Three figures descended a ladder and in the glow of the lantern they carried, Elellanor could see them clearly. The first was Dr. Crow himself, looking even more cadaavverous in the shadows. his two long hands carrying a medical bag. The second was a man she didn’t recognize, shorter and broader, wearing a butcher’s apron stained with substances that gleamed wetly. The third was the white-eyed woman, and Eleanor realized with mounting horror that she could see perfectly well, despite those blank white eyes moving with complete confidence in the darkness.

They crossed to one of the tables and Doc Rose set down his bag and began removing instruments, laying them out with practiced precision. He spoke and his voice in the enclosed space had a resonance that made Eleanor’s bones ache. Specimen 17 has proven remarkably resilient.

The cranial exposure we performed last week has shown no signs of infection and the subject remains conscious and responsive despite removal of approximately 30% of the frontal lobe. Tonight we’ll be exploring the parietal region to determine if spatial reasoning can be isolated and disrupted while maintaining basic motor function.

The breeding program requires subjects who can still perform simple physical tasks but lack the higher reasoning that might lead to resistance or escape attempts. If we can successfully create a stable frontal parietal compromise, we’ll have a template for the next generation. The man in the butcher’s apron grunted in what might have been agreement or anticipation and began preparing one of the tables, adjusting restraints and checking the sharpness of various blades.

The white-eyed woman simply stood motionless, her head slowly turning as if scanning the room. And for one terrible moment, Elellanena was certain those blank eyes focused directly on her hiding spot. But the moment passed, and the woman’s gaze continued its sweep without pausing. Crow was still talking, his voice taking on an almost professorial quality, as if lecturing students who weren’t there.

The challenge with the current generation is that they retain too much awareness of their condition. They remember their previous lives, their families, their sense of self. This creates psychological complications that interfere with the breeding process. The females become hysterical and uncooperative.

The males develop aggressive tendencies that make handling dangerous. But the children born from these pairings, uh, now they’re showing much more promising characteristics. Specimen 22, born 8 months ago to subjects 9 and 14, has shown no signs of higher cognition at all. Yet, its physical growth rate is accelerated by nearly 40%.

It responds to basic commands, accepts whatever food is provided, and displays no emotional attachments whatsoever. That’s our future template. That’s what we’re working toward. A completely compliant research subject that can be bred in perpetuity, providing an endless supply of specimens for our work without the inconvenience of procuring them from the outside world.

Elellanena’s mind was reeling, trying to process what she was hearing. Breeding program. Next generation children born to subjects. Dr. The Crow wasn’t just experimenting on the deformed and mentally afflicted children who’d been brought here. He was breeding them, creating new generations specifically for the purpose of experimentation. Children who would never know anything except the horror of this place.

The scope of the atrocity was beyond anything she’d imagined. This had been going on for years, possibly decades, if his father had started the program at Riverside. How many children had died here? How many were currently imprisoned in the floors above, being subjected to procedures that destroyed their minds while keeping their bodies alive for further use? She needed to get out, needed to get her information to authorities who could stop this, but her body refused to move. She was paralyzed with horror and terror in equal measure, watching as Dr. Crowe and his assistant began walking toward the stairway, presumably to bring down their next victim. They were halfway to the stairs when the whiteeyed woman spoke, her flat, emotionless voice cutting through the cellar like a knife. There is someone else here, female, hiding behind the fourth column on the eastern wall. She has been here approximately 17 minutes.

Elellanena’s blood turned to ice. Dr. Crows stopped walking and turned. Those disturbing eyes scanning the darkness with sudden intensity. Bring her to me, Milisent. gently now. We need her conscious and undamaged for the initial evaluation. The white-eyed woman, milisent, moved with a speed that seemed impossible, crossing the distance between them in seconds, her long-fingered hand closing around Elellanena’s throat before she could even attempt to run.

The grip was inhumanly strong, lifting Elellanena off her feet, cutting off her air with precise pressure that kept her conscious, but unable to scream. Millisent carried her back to Crow as easily as one might carry a doll and deposited her on one of the operating tables, those white eyes staring down at her with neither malice nor mercy, just blank evaluation.

Crow approached slowly, his head tilted to one side in a gesture that reminded Ellaner of a bird examining an insect. Well, well, a visitor, how unexpected and how remarkably foolish. He reached out and touched Elellanena’s face with one of those two long fingers, tracing the line of her jaw, and his skin was cold as ice. You’re the school teacher from the village, aren’t you, Elellanena Frost? Yes, I’ve seen you watching us with your telescope.

I wondered how long it would take before curiosity overwhelmed your sense of self-preservation. Most people are content to look away from what frightens them, but not you. You had to know. You had to see. Well, now you’ll see everything, my dear. You’ll see it from a perspective very few are privileged to experience.

You’ll see it from inside. He nodded to the man in the butcher’s apron, who began fastening the leather restraints around Elellanena’s wrists and ankles, pulling them tight enough to cut into her skin. She tried to fight, tried to scream, but Millison’s hand was still at her throat. That terrible pressure never wavering. Dr. Crow walked to his medical bag and began removing instruments, holding each up to examine in the dim light. The question is, what do we do with you? Killing you outright would be wasteful, and I despise waste. But you’re clearly too old for the breeding program, and your genetic background is unknown. However, he paused, selecting a long, thin blade that gleamed wickedly.

However, you possess something that most of our subjects lack. You possess an educated mind, a functioning intellect, a sense of self that’s been cultivated through years of learning and experience. That makes you perfect for a rather special experiment I’ve been wanting to attempt.

You see, I’ve successfully isolated and disrupted various aspects of cognition in my subjects, but I’ve never had the opportunity to do so in a subject who could articulate the experience. You, Miss Frost, are going to help me understand exactly what happens to consciousness when we systematically remove the parts of the brain responsible for creating it.

You’re going to describe for me in as much detail as possible what it feels like to stop being human. The scream that tore from Elellanena’s throat was muffled by the leather gag that Millisent forced between her teeth with efficient brutality, pulling the strap so tight that Elellanena felt her jaw might dislocate.

Crow tuted disapprovingly, setting down his blade and shaking his head with what appeared to be genuine disappointment. Now, now, Miss Frost, screaming wastess energy and accomplishes nothing. You’ll need to conserve your strength for the work ahead. Besides, no one can hear you down here. These walls are three feet thick, and we’re 40 ft underground. You could shriek until your vocal cords ruptured, and the only people who would notice are already well accustomed to such sounds.” He gestured to the man in the butcher’s apron, who Eleanor now noticed had scars running across his own throat. Thick raised lines that suggested his voice had been deliberately destroyed. My assistant here, whom I call simply butcher because his original name is irrelevant, learned that lesson years ago when he first arrived as a subject. He screamed for 3 days straight during his initial procedures.

Now he’s one of my most valuable helpers. Aren’t you, butcher? The man nodded, his expression never changing, and Eleanor realized with creeping horror that his eyes, while not white like milisence, had a glazed quality that suggested whatever had been done to him, had left him with about as much free will as a puppet.

Crow began removing more instruments from his bag, laying them out in neat rows on a metal tray that Butcher held steady. scalpels of varying sizes, bone saws, clamps, retractors, needles, and thread, and strangest of all, what appeared to be small metal hooks attached to fine wires. I won’t be performing the main procedure tonight, Dr. Crow continued conversationally, as if discussing the weather rather than Elellanena’s impending vivisection. You need to be properly prepared first, which takes several days. The subjects must be gradually weaned off solid food and transition to a liquid diet to minimize complications from the bowels during surgery. You’ll need to be bathed and shaved, of course.

And most importantly, you need to understand exactly what’s going to happen to you. I find that anticipation is almost as valuable as the procedure itself for studying the mind’s response to existential terror. He moved closer to the table, leaning down until his face was inches from Elellanena’s, and she could smell his breath, which carried a sickly sweet odor, like rotting flowers.

Here’s what will happen, Miss Frost. In 3 days time, you’ll be brought back to this table. I’ll administer a compound I’ve developed that keeps subjects conscious and aware while paralyzing the body completely. You’ll be unable to move, unable to speak, but you’ll feel everything with perfect clarity.

Then I’ll open your skull, carefully removing sections of bone to expose your brain. The brain itself has no pain receptors, you see, so I can manipulate it directly while you remain conscious. I’ll begin with the speech centers, destroying them methodically while asking you questions and noting at precisely what point you lose the ability to respond.

Then I’ll move to memory centers and you’ll have the unique experience of forgetting your own life while simultaneously being aware that you’re forgetting your childhood, your education, your brother Thomas. Yes, I know all about him. All of it will slip away like water through your fingers while you watch it happen from inside your own dissolving mind.

Delano thrashed against the restraints with renewed desperation, her muffled screams turning into choked sobs. Dr. Crow straightened his expression still one of clinical interest rather than saism which somehow made it worse. After the speech and memory centers, I’ll proceed to the areas governing emotions, spatial reasoning, recognition of faces and objects, and finally the sense of self itself.

By the end, you’ll be awake, aware in some fundamental way, but you won’t know who you are, where you are, or what the concept of you even means. And throughout this entire process, I’ll be taking extensive notes on your physical responses, the dilation of your pupils, your heart rate, any sounds you manage to make. Your suffering will advance human understanding of the brain by years, possibly decades.

Doesn’t that provide some comfort? Doesn’t that give your death meaning it wouldn’t otherwise have? He actually seemed to expect an answer, waiting for a moment as if Elellanena might somehow express gratitude for the opportunity to be tortured to death in the name of his twisted science.

When she only continued to sob and strain against the leather straps, Dr. Crow sighed and nodded to Millisent. Take her upstairs. Cell 14 should be empty since we harvested specimen 19 yesterday. Make sure she’s fed the liquid diet starting immediately and keep her restrained at all times. I don’t want her attempting suicide and robbing us of this opportunity. Station one of the watchers outside her door at all times.

Millisent reached down and with that same terrifying strength simply picked up Elellanena, table and all, and carried her toward the stairs. Elellanena caught a glimpse of Butcher’s face as they passed, and for just a moment, something flickered in those dead eyes.

Something that might have been pity or warning, or simply the ghost of his former self trying to communicate across the void of his destroyed mind. Then they were ascending the stairs, entering the asylum proper, and Elellanena got her first look at the interior of the place that would be her tomb. The hallway Millisent carried her through was narrow and impossibly long, stretching away in both directions, further than should have been possible given the building’s external dimension.

The walls were bare stone weeping with moisture and lit by oil lamps spaced far enough apart that pools of darkness separated each circle of sickly yellow light. Doors lined both sides of the corridor. Heavy wooden things with small barred windows set at eye level. And from behind these doors came sounds that would haunt whatever remained of Elellanena’s life.

Crying, yes, but also laughter that had no humor in it. Rhythmic banging like heads or fists striking walls repeatedly. And strangest of all, singing a child’s voice high and pure. Singing a nursery rhyme that Elellanena recognized from her own childhood. ring around the rosy pocket full of posies. Ashes, ashes, we all fall down.

The voice sang it over and over, never stopping for breath, mechanical in its perfection. And as they passed that particular door, Elellanena glimpsed through the barred window, a girl of perhaps 10 years old, naked and filthy, standing in the center of an empty cell and singing to the wall. The back of the girl’s head had been partially removed. a section of skull simply absent, covered with what looked like a glass plate through which pink gray brain tissue was visible, pulsing with each heartbeat. Millison showed no reaction to any of this, carrying Elellanar and her table with mechanical efficiency, turning corners that seemed to appear from nowhere, ascending stairs that creaked under their combined weight, moving deeper into the asylum’s impossible architecture. They passed other figures in the hallways and Eleanor realized these must be the other subjects who had been successfully transformed into servants like Butcher and Millisent. Some were missing limbs replaced with crude prosthetics or simply absent.

The stumps wrapped in stained bandages. Others had visible modifications to their heads, metal plates bolted directly to their skulls, wires emerging from these plates and trailing behind them like horrible tails. One figure, a young man who couldn’t have been more than 20, had no eyes at all, just smooth skin where his eye socket should have been.

Yet, he navigated the hallway with perfect confidence, pushing a cart loaded with buckets of something that Elellanar’s mind refused to identify. All of them moved with that same puppet-like quality, responding to commands that Eleanor couldn’t hear, their faces uniformly blank of anything resembling human emotion or will.

They finally arrived at a door marked with the number 14 in tarnished brass, and Millison set the table down long enough to produce a key from somewhere in her tattered uniform, and unlock it. The cell beyond was perhaps 8 ft square, completely bare, except for a drain in the center of the floor, and chains bolted to the walls. The smell was overwhelming, a concentrated version of the stench that permeated the entire asylum, and the walls were covered in scratches, desperate clawing marks where previous occupants had tried to dig their way to freedom through solid stone. Nillison transferred Eleanor from the operating table to the wall chains with practice efficiency, attaching manicles to her wrists and ankles that allowed her minimal movement but prevented her from reaching the door or doing anything useful. The gag remained in place and Millisent checked its tightness with fingers that pressed hard enough to leave bruises.

Then, without a word, without any acknowledgement that Elellanena was a human being suffering in terror, Millisent left, taking the operating table with her and plunging the cell into complete darkness as the door swung shut and locked with a sound of terrible finality.

Eleanor hung there in the darkness, her arms already aching from the position, her jaw screaming in pain from the gag, her mind fragmenting under the weight of what she’d seen and what awaited her. She tried to think practically, to plan escape, to maintain the scientific detachment that had served her so well in her studies.

But panic kept crashing through her thoughts like waves destroying a sand castle. She was going to die here, and not just die, but be systematically destroyed. Her mind carved apart piece by piece, while she remained conscious to experience every moment of her own obliteration. The only mercy was that eventually it would be over. But even that mercy was tainted by the knowledge of how long Dr. Crow could keep someone alive during his procedures, how many hours or days he might stretch out her torture in the name of his research. She thought of her students, who would be told she’d fallen ill or run away or suffered some other convenient fiction. She thought of her brother Thomas and wondered with sick certainty if he’d ended up in a place like this, if he’d suffered these same horrors before death finally released him. She thought of all the children in the cells around her, the ones who were being bred like livestock for the sole purpose of providing fresh subjects for Dr. Crow’s experiments. Time became meaningless in the absolute darkness of the cell. Eleanor drifted in and out of consciousness. her body’s exhaustion eventually overriding even her terror. She dreamed of her classroom, of her students faces turning toward her expectantly. But when she tried to speak, she found her mouth had been sewn shut.

And when she reached up to tear out the stitches, she discovered her hands had been replaced with surgical instruments. She woke screaming into the gag, thrashing in her chains until her wrists bled from the friction and the pain brought her back to horrible reality. The darkness was no longer complete. Thin gray light was seeping under the door, suggesting dawn had come to the outside world, though no sunlight would ever penetrate this deep into the asylum’s depths.

The door opened without warning, and Eleanor flinched away from the sudden brightness of the lantern that Millisent carried. Behind her came a young girl, no more than 12 years old, carrying a wooden bowl and a funnel attached to a long rubber tube.

The girl’s appearance was shocking in its normaly compared to the other servants Elellanena had seen. She looked like any village child, thin and pale certainly, but with all her limbs intact and no visible modifications to her body. Her eyes were a startling blue, clear and focused. And for a moment, Elellanena felt a surge of hope that perhaps this child retained enough humanity to help, to show mercy, to do something to prevent the nightmare that was coming.

Then the girl spoke, and that hope died as quickly as it had sparked. Her voice was completely flat, devoid of any inflection or emotion. The words emerging in a mechanical cadence that made it clear whatever humanity she’d once possessed was long gone. Subject 773 requires feeding. Liquid diet protocol day one.

Compliance is mandatory. Resistance will result in forced insertion of feeding tube through nasal passage. Confirm understanding. Elellanar could only stare at her in horror, unable to respond with the gag still filling her mouth. The girl seemed to take her silence as confirmation and nodded to Millisent, who reached down and loosened the gag just enough to pull it from Elanar’s mouth, leaving it hanging around her neck.

Elellanar gasped in air, her jaw feeling like it might never close properly again, and tried to speak. “Please, you have to help me. I know you’re just a child. I know they’ve done something to you, but please, there must be some part of you that remembers what it was like to be free, to be human. The girl’s expression didn’t change at all.

Those blue eyes showing no recognition that Elellanena had even spoken. She simply moved forward with the bowl and funnel, and Elellanar could see now that the liquid in the bowl was gray and thick with an odor that made her stomach heave. “Please don’t do this. Please.” The girl tilted her head in a gesture that was eerily reminiscent of Dr. Crow’s bird-like examination.

Subjects do not require emotional comfort. Subjects require only sustenance adequate to maintain organ function for duration of research protocols. Open mouth for voluntary feeding or feeding tube will be inserted through nasal passage. Choose. It wasn’t a threat delivered with malice, just a simple statement of fact. and somehow that made it more horrible than if she’d been actively cruel.

Eleanor opened her mouth, knowing resistance was futile and would only result in more pain. And the girl inserted the rubber tube, pushing it down Eleanor’s throat until she gagged and choked. Then she began pouring the gray liquid from the bowl into the funnel, and Eleanor felt it flowing down into her stomach, cold and vile, tasting of rendered fat and something metallic that might have been blood.

She tried not to vomit, knowing she might choke on it, and focused on breathing through her nose until the ordeal was finished. The girl removed the tube with the same mechanical efficiency she’d shown throughout, wiped Eleanor’s mouth with a rag that smelled of disinfectant, and replaced the gag, tightening it once more to its previous position.

Feeding complete subject 73 will receive next feeding in 12 hours. monitoring will be continuous. Then she and Millisent left and Elellanena was alone again in the darkness, the vile liquid sitting heavy in her stomach, her mind screaming with the knowledge that this was only the first of three days of preparation before Dr. Crow would begin his real work.

The next two days passed in a haze of suffering that Eleanor’s mind could barely process. She was fed twice daily with increasing amounts of the gray liquid which her body initially rejected through violent vomiting until there was nothing left to expel. She wasn’t allowed to clean herself and the indignity of soiling herself in the chains while unable to move away from her own waste added a layer of psychological torture to the physical suffering.

Several times she heard screaming from nearby cells, sometimes lasting for hours, sometimes cutting off with sudden and absolute finality that was somehow worse than the screaming itself. Once in what might have been the middle of the second night, she heard children laughing, and the sound was so unexpected and wrong in this place that she thought she might finally be losing her sanity.

The laughter went on for perhaps 10 minutes, high and bright and completely devoy of joy, mechanical laughter like windup toys, and then it stopped as abruptly as it had begun, leaving silence more oppressive than any sound. On what Eleanor believed was the morning of the third day, though time had lost all meaning in the perpetual darkness, Millisent arrived with two male servants and began unchaining her from the wall.

Elellanena’s legs wouldn’t support her weight, muscles atrophied from three days of immobility, and they simply dragged her from the cell, her feet trailing behind her, her head lolling on her neck. She was taken to a room that was tiled floor to ceiling in white ceramic with a drain in the center and what appeared to be a surgical table modified with straps and a built-in water reservoir.

The men stripped away her filthy clothes without ceremony or apparent interest in her nudity. treating her body like an object to be cleaned rather than a person. They placed her on the table and began scrubbing her with brushes that scraped her skin raw, paying particular attention to her scalp, which they shaved completely, removing every hair with a straight razor that nicked her repeatedly, drawing blood that mixed with the water slooing off the table into the drain. Throughout this degrading process, Elellanena tried to detach her mind from her body to retreat into memories of better times. But Dr. Crowe had apparently anticipated this defense mechanism. As the men finished their work and began drying her with rough towels, he entered the room carrying a small wooden case. Still with us, Miss Frost. Good.

I was concerned the preparation might have broken your spirit prematurely, and that would diminish the value of the research. The mind I’m about to explore needs to be intact, at least initially. He opened the case and removed a syringe filled with clear liquid. This is the compound I mentioned earlier, a synthetic derivative of several plant-based alkyoids combined with certain minerals. It produces a state of complete muscular paralysis while heightening sensory perception and maintaining full consciousness.

You’ll be unable to move, unable to blink, unable to breathe on your own. So, we’ll need to mechanically ventilate you throughout the procedure, but you’ll feel everything, understand everything, and remember everything right up until the moment I destroy the structures responsible for memory itself.

Isn’t science magnificent? He injected the compound directly into Elellanena’s neck and within seconds she felt her body beginning to stiffen. Her muscles locked into position. Her lungs froze midbreath. Her heart seemed to stutter before settling into a slow labored rhythm. She tried to scream and couldn’t. Tried to thrash and couldn’t. Could only stare up at Dr. Crow’s face as it swam in her vision. He lifted one of her eyelids, checking the pupil’s dilation, and nodded with satisfaction. Perfect response. The paralysis is complete, but your awareness is heightened. Exactly as intended. Can you hear me, Miss Frost? Blink if you understand. She tried with every fiber of her being to blink and couldn’t. Dr. Crow chuckled. Ah, of course. The blinking reflex is also paralyzed. No matter. Your vital signs indicate consciousness and comprehension. That’s sufficient. He gestured to the servants who lifted Elellanena’s rigid body and carried her from the bathing room down another series of impossible corridors and back to the cellar where her nightmare had begun.

The operating table she’d first been strapped to was prepared and waiting. But now there were additional apparatus arranged around it. A leather bellows connected to a tube that would be forced down her paralyzed throat to breathe for her. metal frameworks positioned to hold her head absolutely motionless.

Bright oil lamps arranged to illuminate her skull from multiple angles and most terrifying of all, a standing mirror positioned so that she would be able to see her own face, watch her own destruction, bear witness to her mind being carved away piece by piece.

They placed her on the table and began connecting the breathing apparatus, and Eleanor felt the tube being pushed down her throat, felt the bellows begin their mechanical rhythm of forcing air into her lungs and then releasing, breathing for her in a parody of life. Doc Crow’s face appeared above her, and he was smiling now, a small expression of anticipation that transformed his cadaavverous features into something genuinely demonic.

We’re ready to begin, Miss Frost. Your contribution to science starts now. But before Drow could make the first incision, before he could begin his systematic destruction of Eleanor’s mind, something happened that changed everything. The door to the cellar burst open with a crash that echoed through the underground space, and down the stairs came stumbling a boy who couldn’t have been more than 14 years old.

His appearance was shocking, his body twisted and malformed in ways that marked him as one of the asylum subjects. But his eyes, unlike those of the servants, were alive with intelligence and desperate determination. He was bleeding from multiple wounds, dragging one leg that was bent at an impossible angle, and clutching in his hands what appeared to be a key ring with dozens of keys.

Behind him, Eleanor could hear sounds of chaos erupting in the asylum above. Children’s voices raised not in pain but in something that might have been rage and the crashes and thuds of violence occurring on multiple floors. The boy stumbled to Eleanor’s table, his twisted hands fumbling with the restraints.

And when he spoke, his voice was thick and difficult to understand. His mouth malfformed, but the words were clear enough. They’re coming. We’re all coming.

News

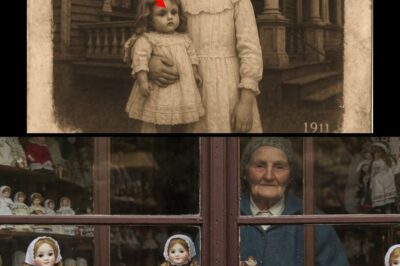

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze…

Little girl holding a doll in 1911 — 112 years later, historians zoom in on the photo and freeze… In…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next Left Everyone Speechless…

Billionaire Comes Home to Find His Fiancée Forcing the Woman Who Raised Him to Scrub the Floors—What He Did Next…

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn

The Pike Sisters Breeding Barn — 37 Men Found Chained in a Breeding Barn In the misty heart of the…

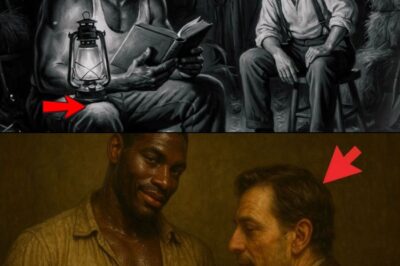

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras.

The farmer paid 7 cents for the slave’s “23 cm”… and what happened that night shocked Vassouras. In 1883, thirty…

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894)

The Inbred Harlow Sisters’ Breeding Cabin — 19 Men Found Shackled Beneath the Floor (Ozarks 1894) In the winter of…

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched

Three Times in One Night — And the Vatican Watched The sound of knees dragging across sacred marble. October 30th,…

End of content

No more pages to load